1. Background

Leptospirosis, a neglected tropical disease caused by pathogenic bacteria of the genus Leptospira, represents a significant public health concern due to its wide distribution and the severe health impacts it imposes on both humans and animals (1). In humans, leptospirosis is also commonly referred to as "rice field fever" or "Weil’s disease", depending on the severity of the infection, and can manifest clinically with a wide range of symptoms from mild flu-like illness to severe complications including jaundice, renal failure, hemorrhage, and multi-organ dysfunction (1, 2). This spirochetal infection is primarily transmitted through direct or indirect contact with contaminated water sources, making it particularly relevant in regions with abundant rainfall and poor sanitation.

Northern Iran is an area where such conditions prevail, increasing the risk of leptospirosis outbreaks, especially among native workers in connection with rice fields (2, 3). In agricultural communities, livestock such as cattle and sheep are highly susceptible to leptospirosis, leading to substantial economic losses due to reduced productivity, abortions, and mortality (4). The close interaction between humans and animals in these regions facilitates the transmission of the pathogen, underscoring the importance of understanding its epidemiology. Rodents, which act as asymptomatic carriers, play a crucial role in the persistence and spread of Leptospira by shedding the bacteria into the environment through their urine (5).

The microscopic agglutination test (MAT) remains the gold standard for serotyping Leptospira isolates due to its high specificity. However, MAT requires access to reference laboratories that maintain a panel of well-characterized Leptospira serovars. This limitation makes the test less accessible for routine diagnostics in many regions. In addition, identification of Leptospira by MAT demonstrates insufficient reliability in identifying individual carriers or animals with chronic infections (6). Conversely, molecular methodologies, including polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and DNA sequencing, prove advantageous for detection purposes and for conducting epidemiological research (7). To accurately identify and monitor Leptospira infections, advanced diagnostic tools are essential. Real-time PCR has emerged as a reliable and sensitive method for the rapid detection of Leptospira DNA in clinical and environmental samples (8). This molecular technique offers significant advantages over traditional culture methods, which are time-consuming and less sensitive.

Culture methods, however, remain valuable for isolating live bacteria and conducting further phenotypic analyses (9). Multi locus sequence typing (MLST) is another critical technique used to characterize the genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships of Leptospira strains. Multi locus sequence typing involves sequencing internal fragments of multiple housekeeping genes, providing a high-resolution approach to study the genetic variations within and between Leptospira species (10). This method not only enhances our understanding of the epidemiology and population structure of Leptospira but also aids in tracking the sources and transmission pathways of the infection (11).

Despite these advances, there is a clear knowledge gap regarding the genetic diversity and molecular epidemiology of Leptospira in northern Iran, particularly in the context of rice field-associated transmission among humans and livestock. Previous studies have highlighted the prevalence of Leptospira in various animal reservoirs in Iran. For instance, a study by Zakeri et al. (12) reported a significant presence of Leptospira in both livestock and rodents in different regions of Iran, emphasizing the need for continuous surveillance and control measures. Similarly, a study by Hedayati and Bahmani (2) underscored the role of environmental factors in the transmission dynamics of leptospirosis in rural areas. However, comprehensive molecular characterization of Leptospira isolates from multiple sources in northern Iran remains limited. Understanding the local strain diversity and transmission dynamics is crucial for public health planning and for implementing effective prevention and control measures in high-risk agricultural communities. This study provides an opportunity to address this knowledge gap by applying advanced molecular tools to investigate Leptospira circulation in livestock and rodent populations in the region.

2. Objectives

The objectives of this study are to assess the prevalence of Leptospira in cattle, sheep, and rodents in Amol, northern Iran. For this purpose, we employed real-time PCR for the rapid and sensitive detection of Leptospira in collected samples, utilized culture methods to isolate live Leptospira strains, and applied MLST to determine the genetic diversity and evolutionary relationships of Leptospira strains in the study area. By achieving these objectives, this research aims to contribute to the understanding of leptospirosis epidemiology in northern Iran, ultimately aiding in the development of targeted interventions to reduce the burden of this disease on human and animal populations.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area, Sample Collection, and Ethics

A total of 118 urine samples were collected during June-September 2023. This study was conducted in Amol, Mazandaran province, northern Iran, an area known for its extensive livestock farming. The total sample size was determined based on logistical feasibility and to ensure sufficient representation of the target populations, including rodents and livestock, in the study area. Samples were collected from three primary sources with the following sampling conditions.

Rodent bladder urine (32 samples named U1-U32): Rodents were captured using Sherman live-capture traps strategically placed around rice paddies and livestock areas in rural regions of Amol, northern Iran. A total of 60 traps were set during each trapping session and positioned approximately 10 - 15 meters apart along field margins and near animal shelters. The traps were baited with grains and were checked twice daily (early morning and late afternoon) to minimize stress on the animals. Trapping was conducted for three consecutive nights per site during the summer and autumn of 2023. After capture, rodents were anesthetized, and their bladders were carefully exposed under aseptic conditions while keeping the organ intact. Urine was aspirated directly from the bladder using a sterile 1-mL insulin syringe, with a maximum volume of 0.5 - 1 mL collected per animal, depending on availability. Samples were immediately processed or stored at 4°C for up to 4 hours until further analysis.

Cattle (42 samples, C1 - C42) and sheep (44 samples, SH1 - SH44) from smallholder farms in rural areas of Amol were selected as the target population. Animals were included if they were apparently healthy and over six months of age, which allowed for a representative assessment of leptospiral exposure in the livestock population. Exclusion criteria included animals showing clinical signs of illness or under treatment. Animals were included if they were apparently healthy and over six months of age, while those showing clinical signs of illness or under treatment were excluded. Mid-stream urine samples were collected by gently stimulating urination while the animals were standing, using sterile containers to avoid contamination. All animals were handled carefully to minimize stress. Samples were immediately stored at 4°C and processed within 4 hours.

3.2. Culture and Microscopy

Approximately 1 mL of each urine specimen was inoculated into modified Ellinghausen McCullough Johnson and Harris (EMJH) medium supplemented with 5-fluorouracil, rifampicin, and neomycin (13). The residual urine was subjected to centrifugation at 3500 g for a duration of 15 minutes. The resultant pellet was then utilized for inoculation of modified EMJH medium. The inoculated EMJH media were incubated at 28 to 30°C for a period of 35 days, with observations for Leptospira-like microorganisms conducted weekly using a dark field microscope (13-15). Leptospiral isolates that grew successfully from EMJH medium were transferred to sterile cryovials containing 0.5 mL of culture mixed with an equal volume (1:1) of sterile 20% glycerol solution to protect against freeze damage. Cultures that showed no visible growth after 12 weeks of incubation at 28 - 30°C were considered unsuccessful. The cryovials were subsequently stored at -40°C for long-term preservation.

3.3. DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted from the urine samples using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA was stored at -20°C until tested by PCR. All extracted DNA samples were standardized at 10 - 20 ng/μL using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA).

3.4. Molecular Detection by Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

For the purpose of DNA amplification, a real-time PCR assay targeting the lipL32 gene of pathogenic Leptospira was conducted. The assay was optimized and validated using reference DNA samples of L. interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae, previously preserved at the Pasteur Institute of Iran (North branch). The PCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 25 μL, containing 1× Maxima® SYBR Green I/ROX qPCR master mix (Thermo Scientific, USA), which included Maxima® Hot Start Taq DNA polymerase and dNTPs in an optimized PCR buffer with a final concentration of 2.5 mM MgCl2. Both forward and reverse primers were added to a final concentration of 0.4 μM each, and 2 μL of extracted DNA was used as template. Each run included negative controls (10 μL nuclease-free water) and positive controls (≤ 100 ng of L. interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae DNA).

Polymerase chain reaction amplification was performed using the Rotor Gene Q 2plex HRM system (Qiagen, Germany) with the following cycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 53°C for 30 seconds, extension at 72°C for 30 seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 minutes. Melting curve analysis (70 - 94°C, 0.5°C increments) was performed after a cooling phase at 30°C for 1 minute to confirm the specificity of amplification. The Ct threshold was empirically set at ≤ 35, based on repeated testing of negative controls, low-template reference samples, and positive controls, to reliably distinguish true positives from background signals. All samples were run in duplicate to ensure reproducibility. Furthermore, the assay demonstrated high linearity (R² ≥ 0.99) and amplification efficiency (95 - 102%) based on 10-fold serial dilutions of reference DNA, with a detection limit of approximately 10 genome copies per reaction, confirming the sensitivity and reliability of the method (14, 16).

3.5. Conventional Polymerase Chain Reaction and lipL32 Sequencing

Two sets of primers (real-time PCR primers and a pair designed in the present study for sequencing) were employed to specifically amplify lipL32 genes within L. interrogans. L. interrogans serovar Icterohaemorrhagiae served as the positive control. The 25 μL reaction mixtures comprised 5 μL of 5x PCR buffer, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 0.4 μM of each primer (Table 1), 0.2 mM of dNTP mix, 1.25 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Sinaclon, Iran), and 5 μL of DNA template. The cycling parameters incorporated an initial denaturation at 95°C for 2 minutes, followed by 35 cycles consisting of denaturation at 95°C for 1 minute, primer annealing at 53°C and 55°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute, with an additional extension at 72°C for 5 minutes, concluding with an indefinite holding phase at 4°C. Subsequently, electrophoresis was performed utilizing 1.5% agarose gel in 1x TAE buffer. Three PCR products derived from the positive samples exhibiting the specific bands associated with lipL32 primers were subjected to sequencing analysis (Pishgam Co, Tehran, Iran). The resultant sequencing data were submitted, analyzed, and subsequently compared against the GenBank databases utilizing the basic local alignment search tool (BLAST), which is administered by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Furthermore, multiple sequence alignments were conducted employing ClustalW, facilitated by MEGA X software, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed utilizing the Bootstrap method with a total of 1000 replications (17).

| Target Gene | Sequence (5' to 3') | Annealing (°C) | Product Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| caiB (MLST) | F: CAGATTCCAGGATACCAACTTGCG; R: CGGGTCCAAACGATATGTTACAGG | 56 | 609 | This study |

| gluM (MLST) | F: TGTGGTATTAGCCGCAGGGAAG; R: GCAAATACAGCAATGTCTCCGTTC | 56 | 755 | This study |

| mreA (MLST) | F: TGGCTCGCTCTTGACGGAAAGG; R: CTACGATCCCAGACGCAAGTAAGG | 60 | 628 | This study |

| pfkB (MLST) | F: CGGCAAACACTATGATCGCTCTTG; R: CCCAACGAGTAGATTTCTCCAAGC | 56 | 711 | This study |

| pntA (MLST) | F: AAGCATTCATTTTGCCGATCCTAC; R: CAGTTTCCGCCCATAGAAGAAGC | 54 | 666 | This study |

| sucA (MLST) | F: TCAGATGGACGGGCTCGTGATC; R: GCAGGCTCGTCCGTTTCATTATG | 58 | 657 | This study |

| tpiA (MLST) | F: TCAAACGAGGAAATTATGCGTAAGAC; R: CAGAACCACCGTAGAGAATAGAAATG | 54 | 664 | This study |

| lipL32 (sequencing) | F: CCCAGGGACAAAAACCGTAA; R: ATTTGAGTGGATCAGCGGGC | 54 | 622 | This study |

| lipL32 (PCR/real-time PCR) | F: AAGCATTACCGCTTGTGGTG; R: GAACTCCCATTTCAGCGAT | 53 | 242 | (16) |

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; MLST, multi locus sequence typing.

3.6. Primer Design and Multi Locus Sequence Typing

The MLST was employed to molecularly delineate selected strains isolated from positive cultures. Multi locus sequence typing was executed in accordance with the protocol delineated by Thaipadungpanit et al. (18), incorporating the following housekeeping genes: glmU, pntA, sucA, tpiA, pfkB, mreA, and caiB. In summary, PCR amplification was conducted utilizing Leptospira spp. DNA extracted from positive cultures. Primers for PCR reaction were designed in the present study using oligo primer analysis software v. 7 (Table 1). The PCR products underwent purification, and subsequent sequencing was performed in both directions employing the primers originally utilized for PCR amplification (Pishgam Corporation, Tehran, Iran). The resultant sequences were analyzed employing Chromas and BioEdit software, and these were retrieved from the international database available for public use (https://pubmlst.org/leptospira) to ascertain the allelic profile and to assign the sequence type (ST) (19). After obtaining the sequence of PCR products, the obtained sequences were evaluated with the help of MEGA X software (17). At first, the sequences obtained in forward and reverse readings were aligned and aggregated. Then, using the link related to the NCBI portal, the sequences were compared with the sources registered in the gene bank and with the help of BLAST software. Also, the obtained sequences were registered in the GenBank and the request to receive the accession number for the isolates was sent to the NCBI international portal. In addition, multiple sequence alignments were made by the ClustalW method, using MEGA X software and the phylogenetic tree was drawn using the Bootstrap method with 1000 replications (17).

3.7. Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS version 24.0. Descriptive statistics, including the prevalence of Leptospira in different sample types, were calculated. The association between sample types and Leptospira presence was assessed using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Results of the Culture and Isolation

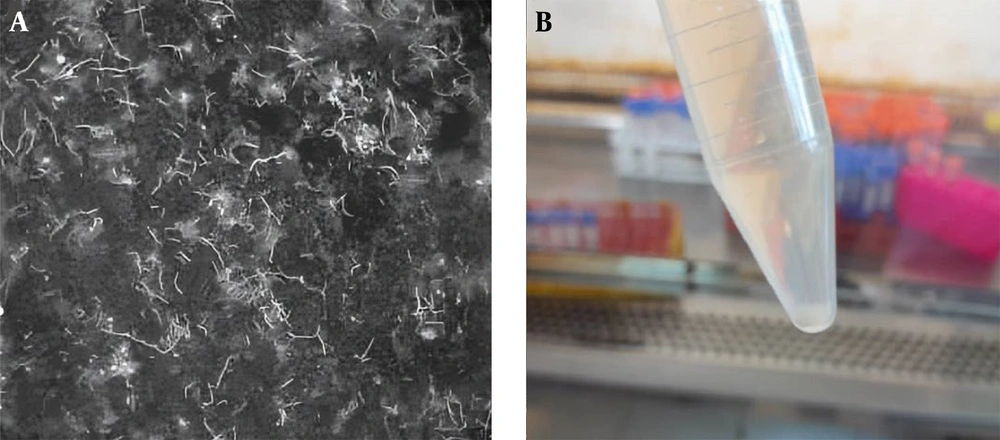

In sampling, all captured rodents were brown rat (Rattus norvegicus). Out of 118 urine samples collected from rat, cattle, and sheep sources, 7/118 (5.93%) samples, including 6/32 (18.75%) rat urine samples and 1/44 (2.27%) sheep urine sample, tested positive for Leptospira through culture and isolation. The positive cultures were observed after 3 - 5 weeks of incubation at 28 - 30°C and were confirmed by dark-field microscopy based on the characteristic motile spiral morphology of Leptospira. No contamination was observed in any of the culture tubes during the incubation period. Figure 1 shows culture tube and dark-field microscope image of a Leptospira isolate. All seven culture-positive samples were also confirmed positive by real-time PCR, and traditional PCR targeting the lipL32 gene yielded positive results for these isolates as well.

A, dark-field microscopy image of Leptospira isolate U7 obtained from rodent urine, showing the characteristic thin, helical, and actively motile spirochetes. The culture was examined at 1000x magnification; B, Culture tube showing growth of Leptospira isolate U7 from rodent urine approximately 4 weeks after inoculation.

4.2. Molecular Detection and lipL32 Sequencing Results

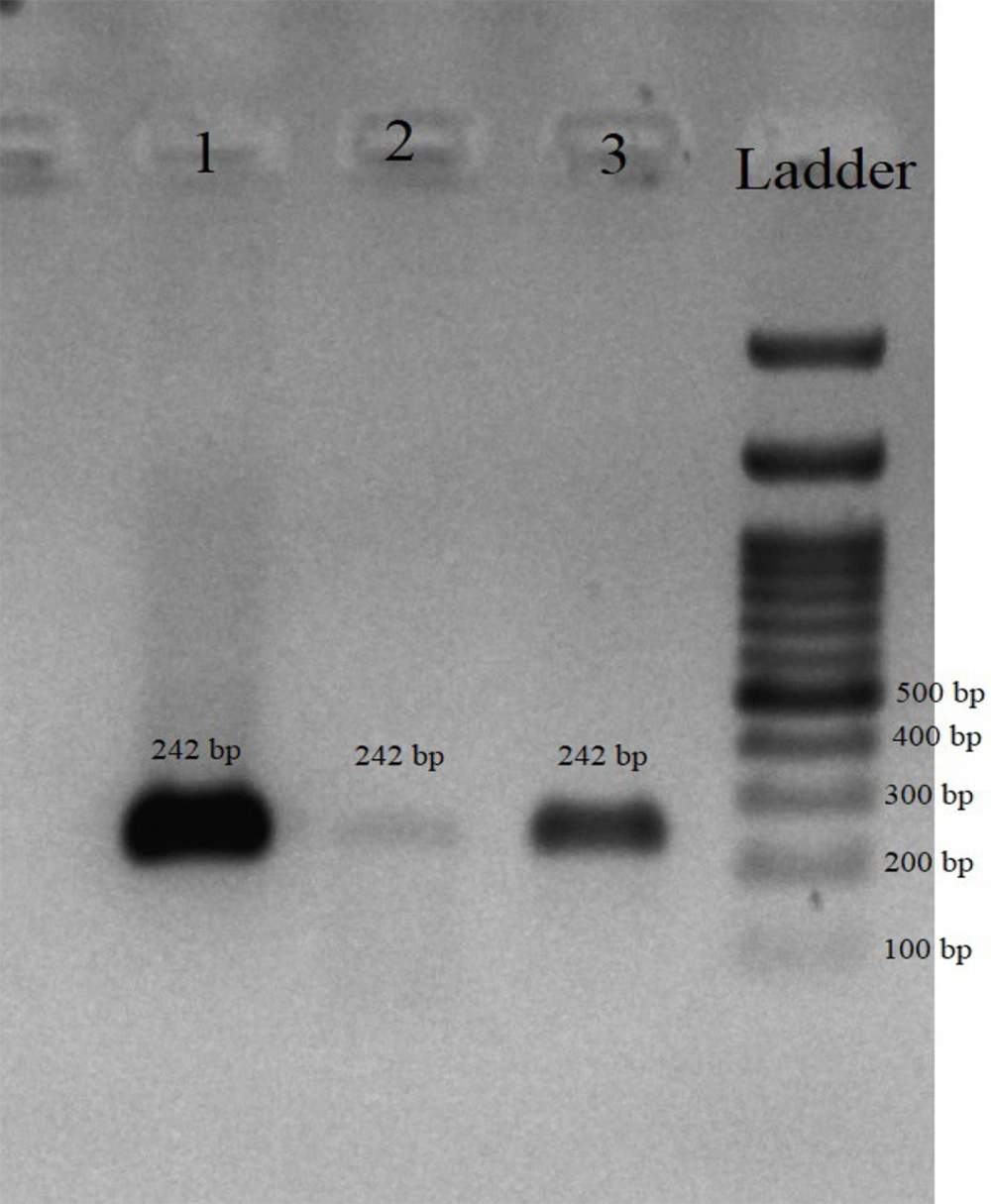

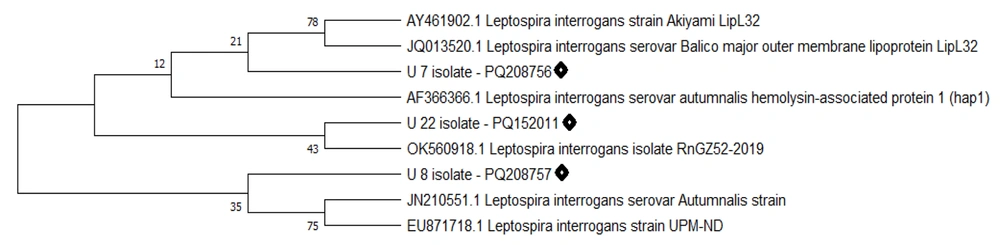

The real-time PCR molecular assay results indicated that 14/118 (11.86%) samples tested positive for the presence of L. interrogans. Table 2 presents the molecular isolation results of Leptospira in the studied samples. All culture-positive and real-time PCR positive samples were positive in conventional PCR targeting the lipL32 gene (Figure 2). The sequencing results of the lipL32 gene were submitted to the GenBank database on the NCBI website and received accession numbers: PQ208756 (U7 isolate), PQ208757 (U8 isolate), and PQ152011 (U22 isolate). Sequence analysis using NCBI BLAST and comparison with GenBank sequences by MEGA software revealed a phylogenetic tree (Figure 3). Comparison of the sequences with other similar sequences showed the similarity of the sequences to GenBank data. Statistical analysis showed that the detection rate of Leptospira was significantly higher in rodent samples than in the other two sources (P < 0.05).

| Sample Type | Number | Positive for Culture | Positive for Simple PCR | Positive for Real-time PCR | MLST Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep urine culture | 44 | 1 (2.27) | 3 (6.81) | 3 (6.81) | ST330 |

| Cattle urine sample | 42 | - | 2 (4.76) | 2 (4.76) | - |

| Rodent urine sample | 32 | 6 (18.75) | 9 (28.12) | 9 (28.12) | ST252 |

| Total | 118 | 7 (5.30) | 14 (11.86) | 14 (11.86) | ST252, ST330 |

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; MLST, multi locus sequence typing.

a Values are expressed as No (%).

Agarose gel electrophoresis of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products amplified using lipL32 gene-specific primers. Lane 1, positive control (Leptospira interrogans reference strain); Lanes 2 and 3, positive samples from rodent and sheep urine; Ladder, 100 bp DNA ladder (size marker). The expected amplicon size is 242 bp, confirming the presence of pathogenic Leptospira.

Phylogenetic dendrogram constructed using MEGA X software based on lipL32 gene sequences from the present study and closely related sequences retrieved from the GenBank database. The tree illustrates the genetic relationships between the isolates of this study (highlighted) and reference sequences.

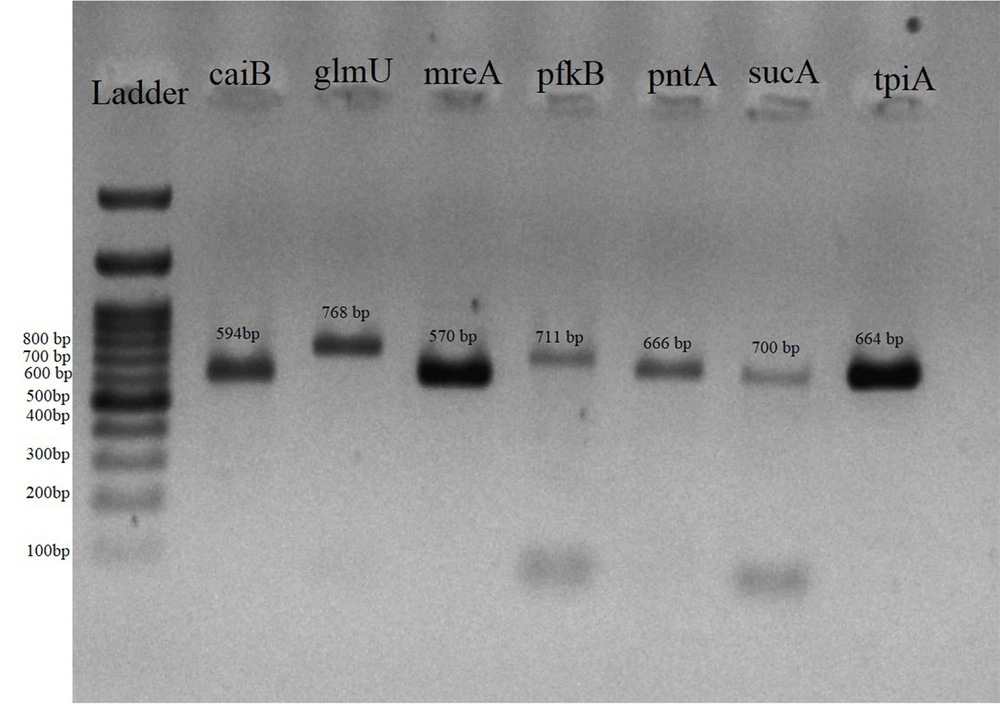

4.3. Multi Locus Sequence Typing Results

The results of MLST were achieved for four isolates from the positive samples, which showed more favorable conditions in real-time PCR results and were selected for molecular typing (Figure 4). The sequencing results of the seven genes evaluated in the MLST method were submitted to the GenBank database on the NCBI website, where they received accession numbers. Table 3 shows the accession number and the allelic profile of seven genes (obtained from pubMLST portal) in selected isolates and MLST procedure obtained from public database for molecular typing and microbial genome diversity of Leptospira (https://pubmlst.org/leptospira). Analysis of the obtained alleles revealed that all selected rodent isolates belonged to MLST type ST252 and the sheep isolate belonged to ST330.

| Isolate | Animal | Source | Allelic Profile (MLST)/Accession Number | Sequence Type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glmU | pntA | sucA | tpiA | pfkB | mreA | caiB | ||||

| U7 | Brown rat | Urine sample | 73 PQ561799 | 1 PQ561801 | 7 PQ561803 | 8 PQ561802 | 15 PQ561800 | 1 PQ561804 | 52 PQ561798 | ST252 |

| U8 | Brown rat | Urine sample | 1 PQ561806 | 91 PQ561809 | 5 PQ561811 | 8 PQ561810 | 15 PQ561808 | 1 PQ561807 | 52 PQ561805 | ST252 |

| U22 | Brown rat | Urine sample | 1 PQ208758 | 91 PQ208753 | 5 PQ208755 | 8 PQ208754 | 15 PQ208752 | 1 PQ561812 | 52 PQ208759 | ST252 |

| SH26 | Sheep | Urine sample | 14 PQ561792 | 3 PQ561794 | 94 PQ561796 | 8 PQ561795 | 74 PQ561793 | 5 PQ561797 | 52 PQ561813 | ST330 |

Abbreviation: MLST, multi locus sequence typing.

5. Discussion

The current study aimed to investigate the occurrence of pathogenic Leptospira species (L. interrogans) in three mammal host samples in the Amol region, providing a comprehensive assessment of its presence in a significant agricultural setting. The methodological approach, including culture-based identification, dark-field microscopy, and molecular assays, offers evidence for the remarkable presence of L. interrogans in the region. We know that rodents are the most important reservoirs of the bacterium in human societies, especially in rural areas (5). But, on the other hand, in the northern regions of Iran, farm animals such as cows and sheep are present and feed in agricultural fields before and after harvest. Therefore, conditions are created for these animals to feed in a common field in a region with a high rainfall amount and come into close contact with each other, which will greatly increase the risk of infection transmission between them (20, 21).

Many studies in Iran have investigated the seroprevalence or molecular detection of Leptospira (22, 23). In a study conducted in Lorestan province, the seroprevalence of L. interrogans was reported as 26.05% in cattle, 22.48% in sheep, and 14.87% in goats, highlighting cattle and sheep as the most exposed species in this region (24). Similarly, a research in Kurdistan province mentioned that the seroprevalence of Leptospira in sheep, goats, and cows was (2/30) 6.7%, (1/31) 3.2%, and 0%, respectively (25). These results are almost consistent with the results of the present study, which showed that Leptospira was not isolated from cattle samples using the culture method while molecular identification using real-time PCR and simple PCR methods confirm the presence of Leptospira in cattle samples. The use of real-time PCR targeting the lipL32 gene, a conserved marker for pathogenic Leptospira, demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in detecting leptospires across different sample types. In the molecular identification and confirmation of culture-positive samples of Leptospira isolates, no difference was observed between the traditional PCR method and real-time PCR, and all positive cases were common. The complementary use of conventional PCR provided additional validation, ensuring reliable detection of the pathogen. This multi-faceted approach is critical, considering that Leptospira can often be underreported due to variability in detection sensitivity across different methods and sample types.

The MAT method is the gold standard for detection of Leptospira serovars, but such research challenges the performance of this method in detecting Leptospira. The MAT method is widely recognized as the gold standard for serological detection of Leptospira, as it allows for specific serovar identification and provides a benchmark for comparing alternative diagnostic approaches. In the present study, although MAT was not applied, the performance of molecular methods including conventional PCR and real-time PCR can be indirectly evaluated against the known sensitivity and specificity benchmarks reported for MAT in the literature. The comparison highlights that molecular techniques, particularly real-time PCR, offer distinct advantages such as rapid turnaround, higher sensitivity for low bacterial loads, and applicability to a wide range of sample types including environmental and asymptomatic animal samples. This underscores the value of these molecular methods in complementing or, in certain contexts, potentially substituting MAT for epidemiological investigations, especially in regions where serovar panels are limited or unavailable (8, 9, 26).

The large number of subspecies and serovars in the genus Leptospira has further increased the need to classify and differentiate them in MAT. Serotyping by the method of leptospirosis reference laboratories is common, but this method is expensive, time-consuming, and very difficult to perform because, to achieve a completely accurate result, the strain of interest must be exposed to at least 200 antisera against standard serovars. In addition, reading the results is also difficult and requires a lot of expertise and experience (26, 27). Owing to the diverse array of prevalent local circulating pathogenic serovars across various geographical regions, serodiagnostic assessments, including MAT or alternative methodologies that do not encompass local serovars and their corresponding protein antigens, exhibit inherent limitations and may inadequately identify the disease as well as perform antibody surveillance in specific locales.

So, the use of sequencing-based methods such as MLST and multiple-locus variable number tandem repeat analysis (MLVA) is becoming more common today and provides more comprehensive and reliable results (28, 29). The utilization of MLST not only facilitated the precise identification of STs but also provided a framework for comparing isolates with global datasets. By submitting these allelic profiles to the PubMLST database, this study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on Leptospira genetic diversity and supports epidemiological tracking of zoonotic and livestock-associated strains. The allelic profiles obtained from MLST analysis in the present study offer valuable insights into the genetic diversity and STs of Leptospira circulating in the region.

The allelic profiles and accession numbers of the MLST genes demonstrate that all rodent isolates belonged to ST252, while the sheep isolate was identified as ST330. The ST252 and ST330 have been frequently associated with rodents and are considered a common ST in L. interrogans strains isolated in Southeast Asia from rat populations (19). The identification of ST330 in a sheep isolate aligns with previous reports that have linked this ST, highlighting its potential adaptation to domestic animal reservoirs (19). To the best of our knowledge, there are no published data reporting the presence of ST252 or ST330 in human cases of leptospirosis. Therefore, any potential transmission of these STs from animals to humans remains hypothetical, and further molecular investigations on human samples are required to assess their zoonotic risk.

5.1. Conclusions

Rodents, as natural reservoirs, were confirmed to be the main source of Leptospira in the Amol agricultural region, with 18.75% of urine samples testing positive via culture. The detection of Leptospira DNA in cattle (2.27%) and sheep urine samples by both conventional and real-time PCR, despite negative culture results in cattle, indicates that these livestock act as secondary reservoirs, potentially facilitating pathogen transmission in shared agricultural environments. The use of both lipL32 gene sequencing and MLST provided complementary molecular confirmation, revealing that rodent isolates belonged to ST252 and the sheep isolate to ST330, thereby enhancing the understanding of local strain distribution. These findings highlight the high environmental contamination in the study area and underscore the importance of targeted surveillance and preventive measures among farm animals and workers in northern Iran.