1. Background

Aspergillosis has been one of the increasing fungal infections in recent decades, with immunocompromised hosts, patients undergoing invasive treatments, and neutropenic patients being the main predisposing factors. Aspergillus section Flavi can cause various forms of aspergillosis in humans, including sinusitis, osteomyelitis, keratitis, pulmonary infections, otomycosis, and endophthalmitis (1). Aspergillus flavus is the second most common cause of aspergillosis, especially in areas with arid and warm climates (1). Species within the Aspergillus section Flavi include A. flavus, A. parasiticus, A. nomius, A. oryzae, A. sojae, and Aspergillus tamarii (2).

The analysis of microsatellite length polymorphism (MLP) using short tandem repeats provides excellent discriminatory power, objective interpretation of typing results, and reproducibility across laboratories. This method has recently been utilized for typing A. flavus (3, 4). Antifungal agents such as itraconazole, amphotericin B, voriconazole, and caspofungin are commonly used to treat both invasive and non-invasive aspergillosis. Luliconazole is a novel imidazole antifungal agent with a unique structure and broad-spectrum activity against common human fungal pathogens.

The pathogenesis of opportunistic aspergillosis relies on various virulence factors of the pathogen. Virulence factors such as biofilm formation, production of urease, lipases, phospholipases, α-amylase enzymes, aflatoxin production, thermotolerance, melanin production, and adhesions have been identified for different Aspergillus species and may play a significant role in the pathogenesis of invasive Aspergillus infections (5).

2. Objectives

This study focused on identifying the genotypic patterns of microsatellite length polymorphism, assessing antifungal susceptibility profiles, and examining biofilm formation in both clinical and environmental strains of A. flavus.

3. Methods

3.1. Fungal Isolates

Twenty-eight isolates of A. flavus were collected using sterile swabs from patients with otomycosis in Ahvaz, a province in southwest Iran, in 2022. Additionally, 22 environmental isolates of the same species were also isolated from soil and air samples during the same time period. All isolates were identified through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) sequencing of the calmodulin gene. A pure culture from each isolate was prepared on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA, Liofilchem, Italy) slants and stored at ambient temperature at the medical mycology laboratory affiliated with the Department of Medical Mycology, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences. The deposited accession numbers of isolates are as follows: LC706757-8, LC706760, LC706762, LC706766, LC706768-9, LC706773-81, LC706784-94, LC706796, LC706799-800, LC858709, LC858711-2, LC858715-6, LC757828, LC757830-1, LC820458-9, LC820462, LC820464, LC820466, LC820469-70, LC820472-3, LC820475, and LC830413-4.

3.2. Microsatellite Length Polymorphism Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted and purified using the method described by Uchida et al. (6). The isolates were grown in Sabouraud dextrose broth (SDB) containing 20 g glucose (Merck, Germany) and 10 g peptone (Difco, USA) in a shaker incubator (100 rpm) at 30–35ºC for 48 hours under aerobic conditions. Colonies were isolated from the culture media using paper filters under sterile conditions, and a small colony was gathered in microtubes filled with 500 μL of lysis buffer and glass beads. Mycelia were homogenized using a SpeedMill PLUS Homogenizer (Analytica, Germany) for 6 minutes, followed by phenol-chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) extraction and isopropanol (Merck, Germany) precipitation. The final DNA pellet was washed, dried, and resuspended in double-distilled water. The DNA samples were stored at 4ºC until use.

In this study, six microsatellite markers were used to genotype A. flavus isolates as described by Hadrich et al. in Table 1 (1). The total volume of the PCR reactions (25 μL) consisted of 12.5 μL Multiplex master mix (Amplicon, Denmark), 0.5 μL of each primer (mix 1 including AFLA1, AFLA3, and AFLA7 forward and reverse primers; mix 2 including AFPM3, AFPM4, and AFPM7), and 2 μL of genomic DNA. The amplification process started with an initial denaturation phase at 94°C for 15 minutes. This was followed by 30 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 seconds, annealing at 54°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds, concluding with a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes. Finally, PCR products were analyzed using capillary electrophoresis (Applied Biosystems, USA), and the fragment sizes were determined using the Genescale 500 IGO size marker (Legalomed, Iran).

| Markers and Primer Sequence (5_ to 3_) | Label | Repeat Unit | Fragment Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFLA1 | FAM | AC | 180 - 290 |

| CGTTGGCATGTTATCGTCAC | |||

| CTACTGAATGGCGGGACCTA | |||

| AFLA3 | HEX | TAGG | 164 - 272 |

| CTGAAAGGGTAAGGGGAAGG | |||

| CACGCGAACTTATGGGACTT | |||

| AFLA7 | TAMRA | TAG | 121 - 293 |

| GCGGACACTGGATGAATAGC | |||

| AACAAATCGGTGGTTGCTTC | |||

| AFPM3 | FAM | (TG) (AT) 6 AAGGGCG (GA) | 188 - 274 |

| CCTTTCGCACTCCGAGAC | |||

| CACCACCAGTGATGAGGG | |||

| AFPM4 | HEX | CA | 184 - 210 |

| AGCGATACAGTTTTAACACC | |||

| TCTTGCTATACATATCTTCACC | |||

| AFPM7 | TAMRA | AC | 188 - 256 |

| TTGAGGCTGCTGTGGAACGC | |||

| CAAATACCAATTACGTCCAACAAGGG |

3.3. Population Structure

The Simpson Index of diversity was used to calculate discriminatory power (DP) using the formula provided at insilico. In the present study, a UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) dendrogram was created using on-line DendroUPGMA: A dendrogram construction utility (http://genomes.urv.cat/UPGMA/).

3.4. Antifungal Susceptibility

In this study, an antifungal susceptibility test was performed based on the broth microdilution method outlined in Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M38 3rd edition (7). Fifty isolates of A. flavus were tested against the following antifungals: amphotericin B, caspofungin, itraconazole, micafungin, anidulafungin, voriconazole (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), luliconazole (APIChem, China), and nystatin (BioBasic, Canada). Standard suspensions were prepared from each isolate on SDA (equivalent to 0.5 McFarland) and then diluted 1:50 in RPMI 1640 (BioBasic, Canada), buffered with MOPS (3-N-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) (BioBasic, Canada). In each well of a microplate, 100 μL of serial dilutions of the antifungal were added to 100 μL of the 0.5 McFarland diluted standard suspension.

After an incubation period of 24 to 48 hours at 35°C, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was assessed for azoles and polyenes, while the minimum effective concentration (MEC) was assessed for echinocandins. Additionally, the geometric mean (GM) of the MIC/MEC values, as well as the MIC/MEC values that inhibited 50% (MIC/MEC50) and 90% (MIC/MEC90) of the isolates, were calculated. The MIC is the lowest concentration of azole antifungals that causes a 50% reduction in visible growth of a microorganism, while polyenes completely inhibit the growth of the microorganism. On the other hand, MEC is defined as the lowest concentration of echinocandin that leads to the growth of small, rounded, compact hyphal forms (7). MICGM represents the mean value that indicates the central tendency of the set of MICs.

Currently, there are no recognized clinical breakpoints for amphotericin B, nystatin, voriconazole, and itraconazole concerning Aspergillus species as per CLSI guidelines. Nevertheless, based on epidemiological cutoff values (ECVs), the following were utilized: amphotericin B (ECV = 4), voriconazole (ECV = 2), itraconazole (ECV = 1), and caspofungin (ECV = 0.5) (8). Additionally, given the analogous drug class of amphotericin B and nystatin, the ECV for amphotericin B was applied to nystatin. Likewise, due to the similarity in drug classes between caspofungin and micafungin/anidulafungin, the ECV for caspofungin was also applied to micafungin/anidulafungin. Luliconazole, a relatively novel antifungal, has been the subject of investigation in recent years and lacks any established breakpoint or cutoff value. All existing literature indicates a variability in sensitivity to this antifungal.

3.5. Biofilm Formation

To assess the ability of A. flavus strains to form biofilms, we followed a method previously described by Ghorbel with minor modifications (9). All isolates of A. flavus were grown on potato dextrose agar (Merck, Germany) for 3 – 5 days at 25ºC, and then a standard spore suspension was prepared (0.4 - 5 × 104 CFU/mL). A 100 μL aliquot of standardized cell suspension was mixed with 100 μL of RPMI 1640 in each well of a flat-bottom 96-well plate. The plate was subsequently placed in an incubator set at 37°C on a shaker operating at 120 rpm/min. After a duration of 24 hours, an additional 100 μL of RPMI 1640 was introduced, and the plate was incubated overnight under identical conditions.

Upon completion of the incubation period, the culture medium was discarded, and the plate was rinsed with sterile ultra-pure water to remove any non-adherent or free cells. Following this, 200 μL of absolute methanol (Parschemical, Iran) was added to fix the biofilm, which was then removed after a period of 15 minutes. A solution of 200 μL of crystal violet (Merck, Germany) at a concentration of 1% v/v was added and allowed to incubate for 5 minutes before being gently washed with sterile ultra-pure water to eliminate any excess crystal violet. In the final step, 200 μL of 100% acetic acid (Merck, Germany) was added to each well, and the absorbance was measured at 620 nm using an ELISA reader (BioTek, USA). The values for biofilm formation were evaluated based on Tulasidas et al. (10). The results were classified as follows: non-biofilm producers (OD ≤ ODc), weak producers (ODc < OD ≤ 2ODc), moderate producers (2ODc < OD ≤ 4ODc), and strong producers (4ODc < OD).

3.6. Statistical Analyses

The analysis of the biofilm results was conducted utilizing a chi-square test provided by Social Science Statistics, with a P-value of less than 0.05 deemed statistically significant.

4. Results

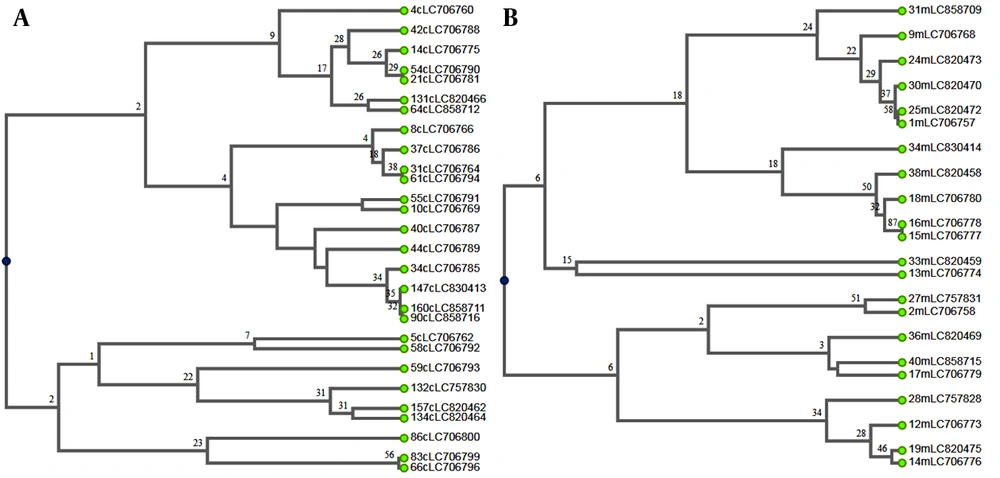

4.1. Population Structure

In the present study, six microsatellite markers were used in clinical samples. The AFLA1 marker exhibited the greatest discriminatory power at 0.9601, whereas the AFPM7 marker demonstrated the least at 0.8280 (Table 2). Microsatellite length polymorphisms of clinical A. flavus isolates identified 28 distinct genotypes across 28 isolates. The highest number of alleles per locus was observed in AFLA7, AFLA3, AFPM7, and AFPM4 markers, with 28 alleles, while the lowest was found in the AFLA1 marker with 24 alleles. The combined discriminatory power of all six primers in clinical isolates was 0.9725.

Additionally, 21 genotypes were identified among 22 environmental isolates of A. flavus. The markers AFLA7, AFLA3, and AFPM4 had the highest number of alleles at each locus, with 22 alleles, while the marker AFPM3 had the lowest number, with 17 alleles. The AFPM4 marker had the highest discriminatory power (D = 0.9697), whereas the AFPM7 marker had the lowest (D = 0.881) (Table 2). The six-primer combination showed a discriminatory power (D) of 0.9738 among environmental isolates. The UPGMA dendrograms of clinical and environmental isolates of A. flavus were illustrated, showing the relationships between these genotypes and the studied variables (Figure 1).

| Markers | Size Range | Alleles (No.) | Genotypes (No.) | DP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | Clinical | Environmental | Clinical | Environmental | Clinical | ||

| AFLA1 | 110-293 | 20 | 24 | 12 | 19 | 0.9421 | 0.9601 |

| AFLA3 | 178-299 | 22 | 28 | 12 | 14 | 0.9264 | 0.9048 |

| AFLA7 | 126-376 | 22 | 28 | 13 | 18 | 0.9394 | 0.9392 |

| AFPM3 | 183-321 | 17 | 25 | 12 | 15 | 0.8897 | 0.8700 |

| AFPM7 | 190-337 | 21 | 28 | 12 | 9 | 0.881 | 0.8280 |

| AFPM4 | 150-367 | 22 | 28 | 18 | 19 | 0.9697 | 0.9524 |

Abbreviation: DP; Discriminatory power

In the present study, microsatellite analysis of 50 clinical and environmental A. flavus isolates revealed 49 distinct genotypes. All clinical isolates in this study exhibited unique genotypes, while only two environmental isolates shared a similar genotype. Marker AFLA7, AFLA3, and AFPM4 exhibited the highest number of alleles (50) at each locus, whereas marker AFPM3 had the lowest (42). Furthermore, AFPM4 demonstrated the highest DP (0.9698) and AFPM7 the lowest (0.8469). The combined DP for all six markers was 0.9777.

4.2. Antifungal Susceptibility Testing Profiles

This study evaluated 50 A. flavus isolates to determine the MIC for eight antifungal drugs: itraconazole, voriconazole, nystatin, micafungin, anidulafungin, caspofungin, luliconazole, and amphotericin B (Table 3). According to the ECVs established by the CLSI M59 guideline, all isolates were characterized as wild-type for voriconazole and caspofungin. Furthermore, based on the ECV definitions, 50% and 12% of the total isolates were non-wild-type for itraconazole and nystatin, respectively. In contrast, 96% and 98% of isolates were non-wild-type for micafungin and anidulafungin, respectively. Regarding amphotericin B, 100% of clinical isolates and 95% of environmental isolates were classified as wild-type. The MIC range for luliconazole against all isolates was 0.0312–0.0019 μg/mL.

| Origin of Isolates and Antifungals | Minimum Inhibitory (Effective) Concentration (MIC/MEC) | Wild-Type | Nonwild-Type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC/MEC Range | MIC/MEC50 | MIC/MEC90 | MIC/MECGM | |||

| All strains (50) | ||||||

| Itraconazole | 0.25 - 2 | 1 | 2 | 1.1809 | 50 | 50 |

| voriconazole | 0.0312 - 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.1150 | 100 | 0 |

| Nystatin | 0.125 - 8 | 1 | 8 | 1.1974 | 88 | 12 |

| Micafungin | 0.25 - 16 | 16 | 16 | 13.3614 | 4 | 96 |

| Anidulafungin | 0.0625 - 8 | 4 | 4 | 3.1601 | 2 | 98 |

| Caspofungin | 0.0039 - 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.0859 | 100 | 0 |

| Luliconazole | 0.0019 - 0.0312 | 0.0156 | 0.0312 | 0.0126 | - | - |

| Amphotericin B | 0.25 - 8 | 1 | 4 | 1.3013 | 98 | 2 |

| Clinical (28) | ||||||

| Itraconazole | 0.25 - 2 | 1 | 2 | 1.1601 | 54 | 46 |

| voriconazole | 0.0312 - 0.25 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.1078 | 100 | 0 |

| Nystatin | 0.5 - 8 | 1 | 8 | 1.4859 | 79 | 21 |

| Micafungin | 0.25 - 16 | 16 | 16 | 11.5972 | 7 | 93 |

| Anidulafungin | 0.0625 - 8 | 4 | 4 | 2.6918 | 4 | 96 |

| Caspofungin | 0.0039 - 0.25 | 0.0625 | 0.125 | 0.0406 | 100 | 0 |

| Luliconazole | 0.0019 - 0.0312 | 0.0156 | 0.0156 | 0.0141 | - | - |

| Amphotericin B | 0.25 - 2 | 1 | 1 | 0.9516 | 100 | 0 |

| Environmental (22) | ||||||

| Itraconazole | 0.25 - 2 | 2 | 2 | 1.2080 | 45 | 55 |

| voriconazole | 0.0312 - 0.5 | 0.125 | 0.25 | 0.1249 | 100 | 0 |

| Nystatin | 0.125 - 2 | 1 | 2 | 0.9098 | 100 | 0 |

| Micafungin | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 100 |

| Anidulafungin | 2 - 8 | 4 | 8 | 3.8759 | 0 | 100 |

| Caspofungin | 0.0625 - 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.2005 | 100 | 0 |

| Luliconazole | 0.0019 - 0.0312 | 0.0078 | 0.0312 | 0.0110 | - | - |

| Amphotericin B | 1 - 8 | 2 | 4 | 1.9379 | 95 | 5 |

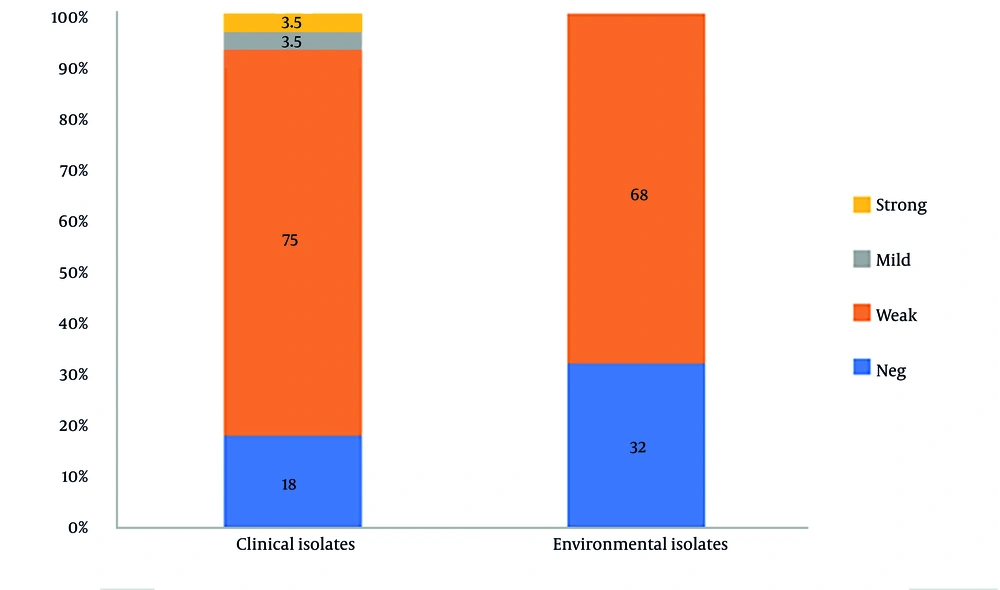

4.3. Biofilm Formation

This study assessed the biofilm-forming abilities of 50 isolates from A. flavus sourced from clinical and environmental samples. A majority of the isolates (72%) were deemed as weak biofilm formers. Additionally, 18% of clinical isolates and 32% of environmental isolates were incapable of forming a biofilm network. Figure 2 illustrates that there was no statistically significant difference in biofilm production between the clinical and environmental isolates (P = 0.2512). Additionally, there was no significant difference between biofilm formation and the following antifungal agents: amphotericin B (P = 0.5703), nystatin (P = 0.4791), micafungin (P = 0.4173), anidulafungin (P = 0.5703), and itraconazole (P = 0.1853).

5. Discussion

The MLP analysis is a highly effective genotyping method for discriminating between distinct genotypes within a fungal species (11, 12). This study genotyped 50 clinical and environmental A. flavus isolates using six microsatellite markers, revealing 49 unique genotypes and a high combined discriminatory power (D = 0.9777). A DP value of 1.0 represents the highest possible discriminatory power. The significant genetic diversity, characterized by a predominance of distinct genotypes, highlights the substantial heterogeneity within the population. The combination discriminatory power of six markers achieved in this study was lower than the value (D = 0.994) reported by Hadrich et al. (1). In our study, the AFLA1 (D = 0.9601) and AFPM4 (D = 0.9697) markers demonstrated the highest discriminatory power in clinical and environmental isolates, respectively. Additionally, among the 50 clinical and environmental isolates analyzed, the AFPM4 marker exhibited the highest discriminatory power (D = 0.9698), with 50 distinct alleles identified. Similarly, in the study conducted by Hadrich et al., the AFLA1 marker displayed the highest level of discrimination (D = 0.903) (1).

In contrast to Taghizadeh-Aramaki et al. (13), who reported a shared A. flavus genotype between clinical and environmental isolates, our analysis revealed no such genetic similarities. Furthermore, while the markers AFLA3, AFLA7, AFPM7, and AFLA1 used by Normand et al. (14) yielded a combined discriminatory power of 0.88, our study observed a significantly higher value (D = 0.9682).

Aspergillus species exhibit broad variation in antifungal susceptibility, a trait documented in both clinical and environmental settings (15-20). In this study, susceptibility testing of 50 clinical and environmental A. flavus isolates to eight antifungal agents revealed that 50% were wild-type for itraconazole. Studies by Gharaghani et al. and Taghizadeh-Aramaki et al. report that itraconazole resistance among Aspergillus species is exceedingly rare (13, 15). While 100% of isolates were wild-type for voriconazole, a broad-spectrum triazole noted for its potent activity against Aspergillus species (21, 22). This finding is consistent with reports by Ghorbel et al. (9), Taghizadeh-Aramaki et al. (13), and Moslem and Mahmoudabadi (16). In contrast, non-wild-type susceptibility rates for voriconazole were reported as 5%, 2.5%, and 14% by Paul et al. (23) Sharma et al. (24), and Choi et al. (25), respectively.

In the present study, 88% of all isolates, and specifically 100% of environmental isolates, were wild-type for nystatin. Although nystatin is established as effective against yeast (26), this study demonstrates its in vitro efficacy against A. flavus. While resistance to echinocandins is generally rare, this study found that 98–99% of A. flavus isolates were non-wild-type to anidulafungin and micafungin. In contrast, 100% of A. flavus isolates were wild-type to caspofungin. This paradox is likely caused by differing resistance mechanisms or limitations in the cross-ECV application of echinocandins.

This study found that 100% of clinical and 95% of environmental isolates were wild-type to amphotericin B, a finding consistent with the report by Taghizadeh-Aramaki et al. (13). However, this contrasts with studies by Moslem and Mahmoudabadi (16) and Dehqan et al. (3), which observed complete resistance or reduced susceptibility to amphotericin B in Aspergillus flavus isolates. In both previous and the present studies, luliconazole showed very low MICs (3, 16, 19, 20). Although no clinical breakpoints or ECVs have been established, its high efficacy and low incidence of resistance are well-documented. Luliconazole is primarily approved for topical treatment of dermatophytosis. Several researchers have demonstrated its in vitro efficacy against systemic agents, suggesting that further research is needed to develop new formulations for systemic therapy.

Biofilms are a key factor in fungal pathogenicity and drug resistance. This study found that 76% of clinical and environmental A. flavus isolates could form biofilms, aligning with Ghorbel et al.'s findings. However, while Ghorbel et al. (9) reported biofilm-forming capacity (with higher production (27) in isolates from keratitis and sinusitis), this study found that 24% of isolates lacked this ability, and 72% produced only weak biofilms. According to the study by Nayak et al. (27), the results on biofilm formation in A. flavus clinical isolates demonstrated a significant biofilm-forming capability, which was associated with enhanced antifungal resistance and virulence. The analysis revealed that biofilm production did not differ significantly between isolates of clinical and environmental origin (P = 0.2512). This limited biofilm formation may be due to the specific environment of the external ear or inadequate gene expression. It seems that biofilm formation by A. flavus in otomycosis does not play an important role in pathogenicity.

Both A. fumigatus and A. niger have a significant ability to form structured biofilms, which is a key trait for A. fumigatus pathogenicity and A. niger's persistence in industrial settings. The formation of complex biofilms, encased in an extracellular matrix, is a well-documented virulence and survival factor for these species, enhancing their resistance to antimicrobial agents and environmental stresses.

5.1. Conclusions

Our study reveals that microsatellite length polymorphism typing serves as an effective method for examining the genetic typing of A. flavus isolates. We note significant genetic diversity within the A. flavus isolates, having identified 49 unique genotypes through the use of a set of six markers (AFLA1, AFLA3, AFLA7, AFPM3, AFPM4, and AFPM7), which yielded a high combination DP value (DP = 0.9777). All A. flavus isolates were found to be wild-type to voriconazole and caspofungin, suggesting that both antifungals exhibit the most favorable susceptibility profile in vitro. Luliconazole showed very low MICs against both clinical and environmental isolates. Although this antifungal was approved as a topical agent, its favorable susceptibility profile against systemic agents requires further research in new formulations. In total, 76% of the isolates demonstrated the ability to form biofilms.