1. Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) account for the majority of deaths worldwide and significantly contribute to escalating healthcare expenses in nearly every nation. Despite advancements in primary prevention, the prevalence of CVDs has risen in recent years. Projections suggest that by 2030, approximately 23.6 million individuals will lose their lives each year as a result of these diseases (1). Numerous studies have highlighted the role of various mechanistic pathways in the development of CVDs, including oxidative stress (OS) (2-4). Research indicates that the elevated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is closely linked to the pathogenesis of CVDs, particularly in conditions such as cardiotoxicity (CTX), myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (MIRI), heart failure (HF), myocardial hypertrophy, and atherosclerosis (5).

Sodium arsenite (SA) is a highly toxic inorganic compound recognized for its potential cardiotoxic effects (6, 7). It is a white, odorless powder that is soluble in water and is commonly utilized in industrial applications, including wood preservation and pesticides (8, 9). In 2017, World Health Organization (WHO), through the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), established a provisional drinking water guideline for inorganic SA set at 10 μg/L (10). Exposure to inorganic SA can occur through ingestion, inhalation, or skin contact. Classified as a carcinogen, it is associated with a range of health issues, such as skin lesions, gastrointestinal problems, and respiratory and cardiovascular complications (6, 8). In terms of its toxicological effects, SA induces OS and triggers inflammatory responses, contributing to damage in cardiac tissue and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (11). Research indicates that SA can lead to arrhythmias and hypertension in animal models, underscoring significant health risks, especially for populations exposed to contaminated water sources (12, 13). Ongoing studies are focused on identifying protective factors or therapeutic strategies to mitigate its CTX, highlighting the necessity for awareness and regulation of exposure in industrial environments (14).

Vanillic acid (VA) is a phenolic acid with a molecular weight of 168.14 g/mol and a slightly yellow hue (15, 16). It is an oxidized form of vanillin, known for its pleasant aroma, and is widely used as a flavoring agent in the food industry (14, 17). The VA is primarily extracted from medicinal plants, particularly the roots of Angelica sinensis, and is produced through secondary metabolic processes in plants (18). It can also be found in trace amounts in various foods and beverages, including olives, cereals, fruits, green tea, juices, beers, and wines (19). The VA can effectively neutralize free radicals and reduce OS, which are critical factors in arsenite-related heart damage (18). Research indicates that VA not only decreases lipid peroxidation but also enhances the activity of natural antioxidant enzymes, providing a protective effect against oxidative damage in cardiac tissues (20). Given these properties, further investigation into VA’s role could reveal its therapeutic potential in mitigating the harmful effects of SA on the heart, highlighting its importance in developing strategies to combat SA-induced CTX.

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

All materials were sourced from accredited suppliers: VA and various reagents were provided by Sigma Aldrich Company, while SA was from Merck Company. Experimental kits were acquired from ZellBio, Germany. Reagents for manual tests, including thiobarbituric acid and DTNB, were also from Sigma Aldrich. Serum factors were measured using a commercial kit from Pars Azmoon.

2.2. Animals

The study involved 30 male mice, each weighing between 23 and 27 grams, obtained from Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences (AJUMS). They were housed in a controlled environment with a temperature range of 22 to 25°C and 55 ± 5% humidity, with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and free access to food and water. All procedures adhered to ethical standards approved by the Ethics Committee of AJUMS (IR.AJUMS.AEC.1403.017).

2.3. Experimental Method

The mice were randomly divided into five groups. Each group consisted of 6 mice and was treated as follows: The control group received saline, the SA group was given drinking water containing 50 ppm of SA, the VA group was administered 100 mg/kg of VA, and treated groups received 50 and 100 mg/kg of VA along with SA at 50 ppm. Mice were exposed to saline or water containing 50 ppm of SA for a total of 8 weeks, and during the final two weeks, the treatment groups received daily oral doses of VA at two different concentrations: Fifty mg/kg and 100 mg/kg. We declare that blinding was implemented throughout the critical stages of our study to minimize bias. The VA doses were selected based on previous studies (15, 16), while the concentration of SA was selected in line with the study conducted by Dutta et al. (21).

2.4. Sample Collection

After 8 weeks, and exactly 24 hours following the administration of the last doses, the animals were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of ketamine at a dose of 100 mg/kg, along with 10 mg/kg of xylazine. Blood was drawn from the heart, centrifuged, and the serum was separated and stored at -70°C until biochemical tests could be conducted. Subsequently, the heart was carefully removed; due to the deep anesthesia, the animals experienced no pain. The remaining heart tissue was stored in special containers in the freezer at -70°C for further analysis of OS factors, inflammation, and protein expression.

2.5. Biochemical Assays

2.5.1. Cardiac Serum Biomarkers

Serum activity of creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), aspartate transaminase (AST), and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) enzymes was measured based on the Pars Azmoon commercial kit.

2.5.2. Cardiac Oxidative Stress and Nitric Oxide

Total thiols (TT) (22), thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) levels (23), and catalase (CAT) activity (24) were measured according to specified studies, while superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity and glutathione peroxidase (GPx) levels were assessed using ZellBio kits and read with a plate reader.

2.5.3. Nitric Oxide Measurement

To measure NO in the cardiac supernatant samples, the methods of ZellBio kits were used and read with a plate reader.

2.6. Cardiac Western Blot Assay

Cardiac tissue was homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer containing 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride. The homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes, and the supernatants were collected for protein analysis. Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford assay, and 50 µg of protein was loaded onto a 10% SDS-PAGE gel before transferring to a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with 5% skim milk for 2 hours, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against GAPDH, PPAR-γ, and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB). Following two washes, membranes were treated with anti-rabbit IgG for 2 hours. Immunoreactive bands were detected using the Excellent Chemiluminescent Substrate (ECL) kit and quantified with a JS 2000 scanner. The expression of PPAR-γ and NF-κB was evaluated by comparing the density of these proteins to that of GAPDH.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The research data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, presenting results as mean ± SD, with (P < 0.05) deemed statistically significant. For normality of the data, the Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted; for homogeneity of the data, Bartlett’s test was automatically conducted when one-way ANOVA was used. All analyses were conducted using Prism 9 software.

3. Results

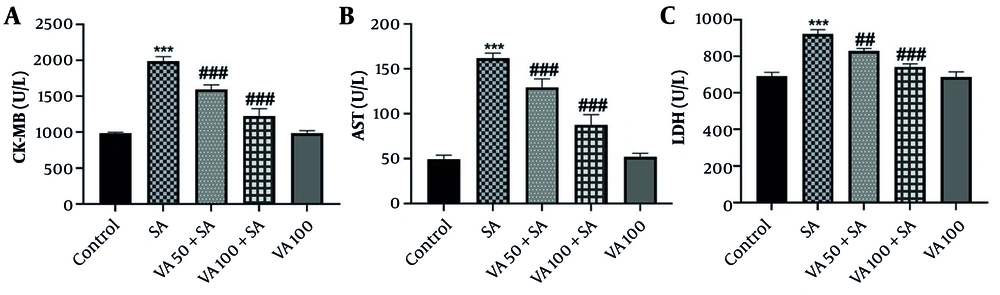

3.1. Effects of Vanillic Acid on Serum Factors

The results in Figure 1 show that SA administration significantly increased CK-MB, AST, and LDH levels compared to the control group (P < 0.001), indicating potential cardiac damage. In contrast, VA treatment in SA-pretreated mice resulted in significant reductions in CK-MB and AST levels (P < 0.001), and also decreased LDH levels (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01). This suggests that VA may have cardioprotective effects, counteracting the harmful impacts of SA.

The effects of vanillic acid (VA) on serum concentration of A, creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB); B, aspartate transaminase (AST); and C, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) in each group. Significant difference compared to the control group (*** P < 0.001). # Significant difference compared to the sodium arsenite (SA) group (## P < 0.01 and ### P < 0.001).

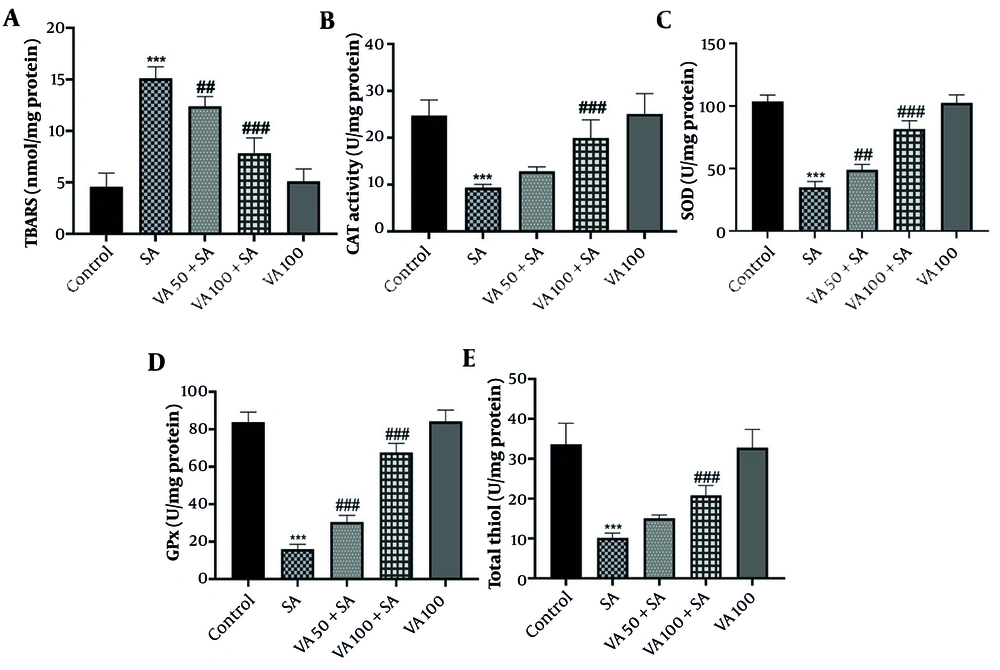

3.2. Effects of Vanillic Acid on Oxidative Stress Factors

In SA-treated mice (Figure 2A), TBARS levels were significantly elevated compared to controls (P < 0.001), while VA treatment led to a notable reduction in TBARS levels (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01). Additionally, OS markers such as SOD, GPx, and CAT decreased in the SA group (P < 0.001) but increased significantly with VA treatment (Figure 2B - E) (P < 0.001 and P < 0.01). This indicates that VA effectively mitigates OS in heart tissue.

Effects of vanillic acid (VA) on A, oxidative stress (OS) thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS); B, catalase (CAT); C, superoxide dismutase (SOD); D, glutathione peroxidase (GPx); and E, total thiols (TT) in cardiotoxicity (CTX) induced by sodium arsenite (SA) in mice. Significant difference compared to the control group (## P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001). # Significant difference compared to the SA group (## P < 0.01 and ### P < 0.001).

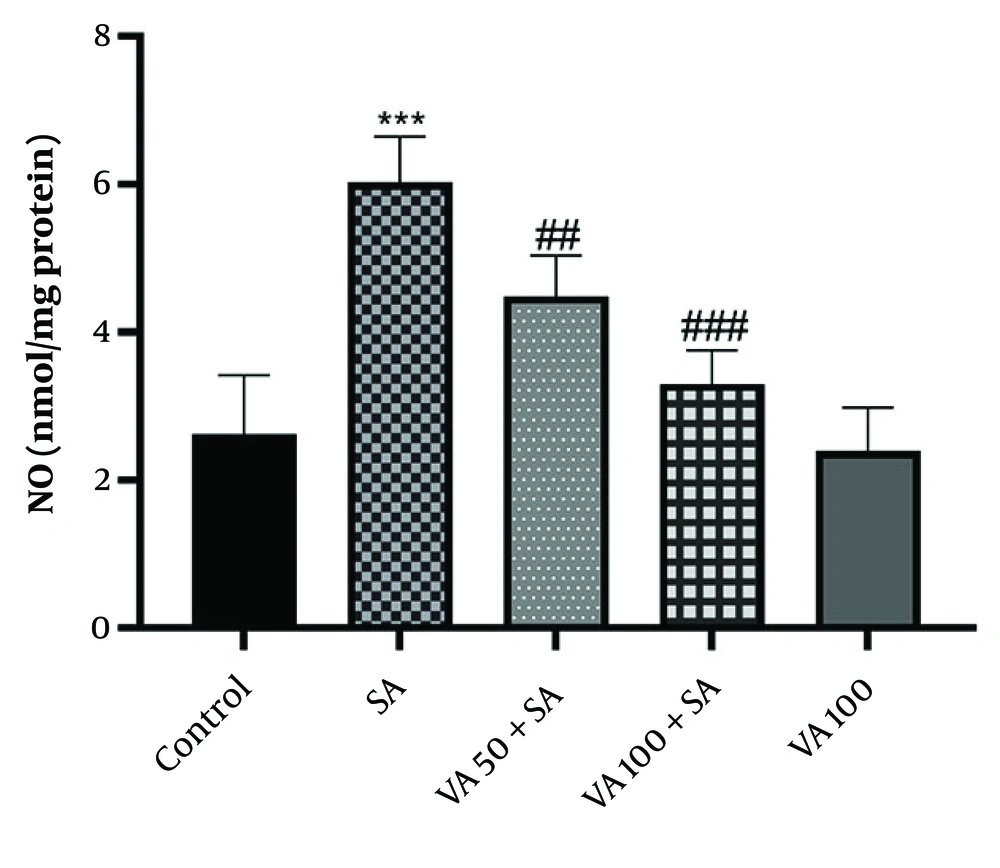

3.3. Effects of Vanillic Acid on Nitric Oxide Levels

The SA group (Figure 3) showed significantly higher levels of NO compared to the control group (P < 0.001), while VA treatment notably decreased NO levels (P < 0.01 and P < 0.001). Therefore, VA treatment effectively reduced the activity of NO.

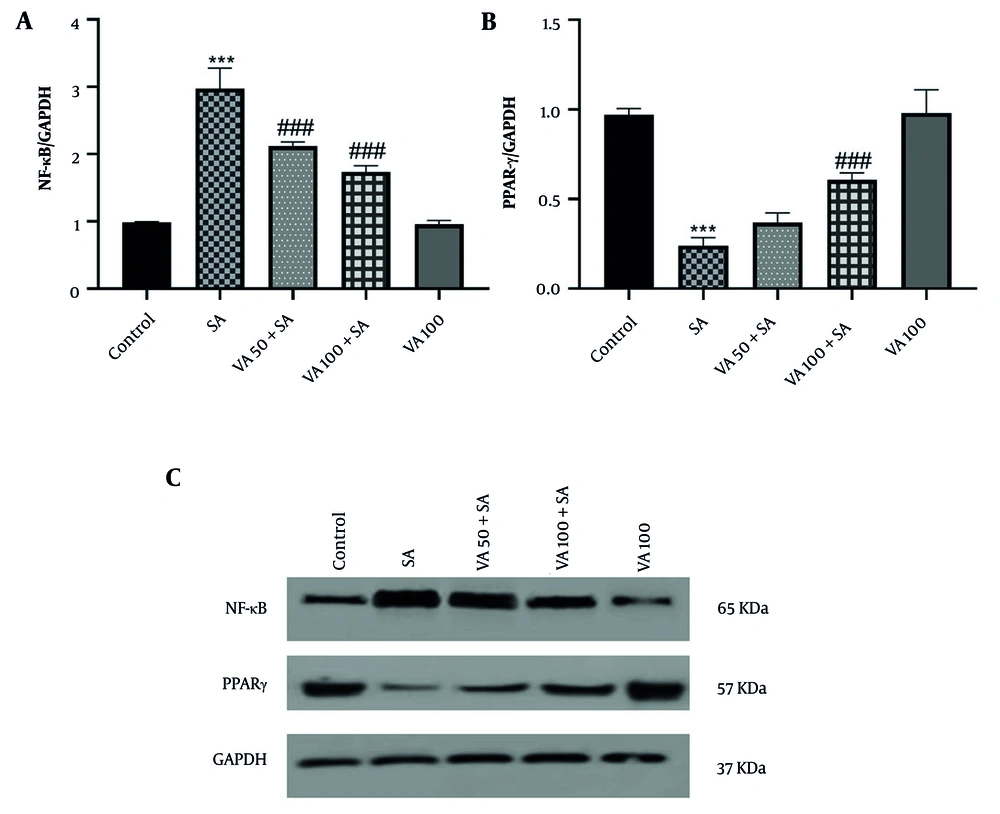

3.4. Effects of Vanillic Acid on Nuclear Factor Kappa B and Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma Protein Expressions

Western blot analysis revealed that NF-κB expression was significantly increased in the SA group (P < 0.001) (Figure 4), while peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) levels were notably lower in the SA group compared to the control (P < 0.001). In contrast, VA treatment significantly boosted PPARγ expression and decreased NF-κB levels compared to the SA group (P < 0.001).

Effects of vanillic acid (VA) on the expression of A, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB); and B, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ); and C, western blot bonds in cardiotoxicity (CTX) induced by sodium arsenite (SA) in mice. Significant difference compared to the control group (*** P < 0.001). Significant difference compared to the SA group (### P < 0.001).

4. Discussion

In the present study, the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of VA on cardiac damage induced by SA have been investigated. In its inorganic form, SA can have destructive effects on the environment, particularly because this substance is abundant in water. It can cause poisoning and chronic diseases in both humans and animals through drinking, including serious skin damage, diabetes, and cardiovascular problems (25). The CK-MB is an isoenzyme predominantly found in cardiac muscle and serves as a crucial biomarker for diagnosing myocardial injury, such as that occurring during a heart attack. Elevated CK-MB levels in the blood indicate damage to the heart muscle. While CK-MB is specific to cardiac tissue, it can also be present in smaller amounts in skeletal muscle, requiring careful interpretation in clinical contexts. In cases of CTX, such as that caused by SA, monitoring CK-MB levels is essential for assessing the extent of cardiac damage and guiding treatment strategies (26).

The AST is an enzyme found in various tissues, including the heart, liver, and muscles, and serves as an important biomarker for assessing tissue damage. Elevated AST levels in the bloodstream indicate cellular injury, particularly in the heart and liver, making it useful for diagnosing conditions such as myocardial infarction and liver disease. In the context of CTX, such as that induced by SA, increased AST levels suggest myocardial damage and can help evaluate the severity of cardiac injury (27). The LDH is an enzyme involved in energy production and is present in various tissues throughout the body, including the heart, liver, kidneys, and muscles. It plays a crucial role in converting lactate to pyruvate during metabolic processes. Elevated levels of LDH in the bloodstream can indicate tissue damage or necrosis, making it a valuable biomarker for assessing conditions such as myocardial infarction and other forms of organ injury. In cases of CTX, these elevations reflect cardiac tissue damage and provide insights into the extent of injury, aiding in diagnosis and treatment decisions (28). Collectively, these biomarkers offer important insights into the severity of cardiac injury resulting from SA exposure, assisting in the diagnosis and treatment of affected patients.

The OS is one of the important factors in maintaining the balance of homeostasis in the body. One of the important factors that can disrupt this balance is toxic substances, and SA is one of these toxins. The SA, by disrupting the balance of homeostasis in the body, interferes with the function of internal antioxidants in the body, including SOD, GPx, etc. (29). In the meantime, SA also increases lipid peroxidation, which is one of the factors that damage cells. The result of this damage ultimately causes tissue damage in the cells. One of the parts of the body where a lot of blood supply occurs is the heart, and SA can penetrate the tissue in greater amounts (7).

The VA can directly activate PPARγ, a key player in managing gene expression linked to inflammation and metabolism. When PPARγ is activated, it can suppress NF-κB signaling, which results in a lower production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (20). By modulating the expression of specific transcription factors, VA can directly reduce NF-κB activity. This reduction results in decreased inflammatory responses and OS in cardiac tissues (30). The VA’s regulation of transcription factors can lead to decreased levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and other inflammatory markers, thereby alleviating cardiac inflammation caused by SA exposure (31, 32). In fact, it can be said that it is one of the most susceptible tissues to damage is heart tissue.

On the other hand, PPARγ serves as a counterbalance to the effects of NF-κB. It plays a protective role by modulating metabolic processes and exhibiting significant anti-inflammatory properties (33, 34). By inhibiting the expression of inflammatory cytokines and reducing OS, PPARγ helps to mitigate the damage caused by SA. The interaction between these two pathways, NF-κB, which promotes inflammation, and PPARγ, which offers protection, highlights a complex regulatory network that is crucial for understanding the mechanisms underlying cardiac injury (34, 35). This interplay is essential not only for elucidating the biological responses to SA but also for developing potential therapeutic strategies aimed at protecting the heart from such injuries. Targeting these pathways could pave the way for novel treatments that enhance cardiac resilience and improve outcomes in conditions characterized by OS and inflammation.

In many studies, VA has been able to significantly reduce OS caused by SA damage. In a study by Baniahmad et al. investigating the effect of VA on doxorubicin-induced CTX, VA was found to reduce levels of LDH, malondialdehyde (MDA), and CK-MB, which is consistent with the results of our study. In fact, in our study, VA also reduced SA-induced CTX by decreasing LDH, MDA, and CK-MB levels (36). Stanely Mainzen Prince et al. investigated the protective effects of VA against cardiac toxicity induced by isoproterenol in male Wistar rats. Administration of VA prior to exposure to isoproterenol significantly improved cardiac biomarkers, reduced lipid peroxidation, increased antioxidant levels, and diminished inflammatory responses. Notably, a dosage of 10 mg/kg proved to be more effective than 5 mg/kg, highlighting the potential of VA as a therapeutic agent in mitigating cardiac damage. These findings suggest that VA may play a crucial role in enhancing cardiac health by counteracting OS and inflammation associated with isoproterenol-induced CTX. The results of our study were also consistent with this study (37).

Various antioxidants can be effective against heart damage caused by SA. In a study conducted by Goodarzi et al., the effect of ellagic acid on SA-induced CTX in rats was investigated. In this study, ellagic acid increased CAT and TT. It also decreased LDH, CK-MB, and AST. The results of our study were also consistent with this study, and VA was effective as an antioxidant agent (38).

The current study presents promising findings regarding the cardioprotective effects of VA against SA-induced cardiac damage; however, it is crucial to acknowledge its limitations, particularly in terms of clinical applicability. The research primarily utilizes rodent models, which may not accurately reflect human physiological responses. Future research must prioritize clinical trials to validate these findings in human populations, establish appropriate dosages, and assess long-term safety and efficacy to ensure that the benefits of VA can be effectively translated into clinical practice.

4.1. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that VA could be a promising treatment for reducing heart injury caused by environmental toxic agents like SA. We believe further research is essential to understand the mechanisms behind these effects and to assess the potential clinical uses of VA in promoting heart health.