1. Background

Radiotherapy (RT) plays a pivotal role in the treatment of various malignancies and is often utilized in conjunction with surgery, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy to effectively eliminate tumor cells (1, 2). The technique of brachytherapy is widely used in clinical RT. The radiation transports its energy by producing reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that affect various components of cells, including proteins, lipids, DNA, RNA, and the cell membrane. Consequently, ionizing radiation has the potential to inflict damage, ultimately leading to cell death (3). During RT, normal tissues surrounding the tumor are also exposed to ionizing radiation; therefore, a major challenge in RT is the collateral damage to surrounding healthy tissues, particularly in proliferative and radiosensitive areas (4). Such damage can induce acute and chronic cytotoxic effects, impairing patients’ quality of life and sometimes leading to the discontinuation of the intended RT (5).

Technological advancements, including conformal RT, intensity-modulated RT, and proton therapy, have been proposed as a variety of interventions to minimize the cytotoxic effects of ionizing radiation (6, 7). Nonetheless, despite these improvements, side effects remain a significant concern. The therapeutic success of RT partly depends on the differential sensitivity between tumor and normal cells; therefore, interventions that selectively enhance tumor radiosensitivity or protect normal tissues are critical (8).

Radioprotectors represent an alternative strategy to protect normal tissues from the cytotoxic effects of ionizing radiation. It is essential to demonstrate that these compounds do not protect tumor cells. Radioprotector compounds are recommended for use in individuals exposed to RT to safeguard them from the lethal effects of ionizing radiation (9, 10). Among synthetic radioprotectors, amifostine is well-known; however, its high cost and associated side effects have driven interest toward alternative natural compounds (11). Herbal medicine is recommended as an alternative to synthetic compounds, which are often considered non-toxic or less toxic. Traditional medicinal plants, valued for their antioxidant, free radical scavenging, and immunomodulatory properties, offer promising radioprotective potential. Understanding their mechanisms is essential to fully harness their therapeutic benefits (12, 13).

Quercus brantii, a species within the Fagaceae family, is widely distributed across various regions of Iran, including Kermanshah, Arak, Astaneh, and Khorramabad. Both the fruit and bark of this plant are composed of diverse bioactive constituents, such as vitamins A, B, and C, pectin, mucilage, quercetin, malic acid, glycosides, alkaloids, saponins, terpenes, steroids, polyphenols, tannins, gallic acid, resin, and ellagic acid. Many of these naturally occurring compounds possess well-established antioxidant properties (14). Moreover, Quercus species have been traditionally recognized for their significant anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, anticancer, and wound-healing effects. Their phytochemical profile is notably rich in flavonoids, tannins, polyphenols, and vitamins, all of which contribute to their potent free radical scavenging capabilities and ability to alleviate oxidative stress (15-17). Given that ionizing radiation primarily exerts its cytotoxic effects through the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), the abundant presence of these compounds in Q. brantii underscores its promising potential as a radioprotective agent by neutralizing deleterious free radicals.

The HT29 cell line, derived from human colorectal adenocarcinoma, was selected for this study due to its well-characterized biological behavior and consistent, reproducible response to ionizing radiation. As a widely accepted in vitro model, HT29 cells provide a reliable platform for assessing cellular viability and cytotoxicity, which are essential for the preliminary screening of potential radioprotective agents. While the primary aim of radioprotection is to safeguard normal healthy tissues, evaluating the effects on cancer cell lines such as HT29 offers valuable initial insights into the safety profile of the compound and its potential impact on tumor cells. This approach aids in guiding subsequent investigations involving normal cell models and in vivo studies.

2. Objectives

The present study aims to investigate and evaluate the radioprotective effects of Q. brantii on the HT29 cell line subjected to ionizing radiation exposure.

3. Methods

All chemicals and solvents were purchased from Merck and Sigma-Aldrich companies. They had the highest purity and analytical grade and were used without further purification. The cell culture analysis was undertaken on the HT29 cell line. This cell line was initially derived from a human colorectal carcinoma and was sourced from the Pasteur Institute of Iran.

3.1. Preparation of Quercus brantii Extract

The tree bark of Q. brantii was collected from the Abdanan region in Ilam province. The collected samples were identified by the Medicinal Plant Research Center, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran. A voucher specimen (No.: A19111112FP) was kept at the Herbarium of the Medicinal Plant Research Center. The bark pieces of Q. brantii were washed with distilled water and then air-dried. Initially, 200 g of the sample was manually crushed into a fine powder. The powder was then immersed in ethanol and left to soak for 48 hours at room temperature while being shaken multiple times using a shaker. After filtering the mixture, the volume of the extract was reduced by about one-third using a rotary evaporator. Finally, the extract was completely concentrated and dried using a freeze-dryer (18). The extract of Q. brantii was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to achieve a final concentration of 1% v/v, which was confirmed to be non-toxic before application.

3.2. Cell Culture

The cells were grown as an attached monolayer in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium 1640 (RPMI 1640) enriched with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin in T25 flasks at 37˚C in 5% CO2, 95% air, and complete humidity. The subculture was carried out two or three times per week. The passage range was 15 to 20 after receiving the HT29 cell lines from the source.

3.3. MTT Assay

The cytotoxicity was evaluated by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (19). HT29 cells, at a density of 104, were plated in 100 µL of culture media in each well of 96-well plates and incubated for 24 hours. Then, the supernatant was carefully removed, and 30 µL of MTT reagent was added to each well. The plates were incubated for 4 hours, after which the resulting formazan crystals were dissolved with 150 µL of DMSO. The absorbance for each well of the 96-well plates was measured using an ELISA reader (Bio-Tek Instrument, Inc., USA) at a wavelength of 570 nm. The cell survival was calculated by dividing the absorbance of treated cells by that of control cells, multiplied by 100 (20).

3.4. Evaluating Different Doses of Radiation on HT29 Cells

A preliminary investigation was conducted to assess the sensitivity of HT29 cells to ionizing radiation (X-rays). Plates intended for radiation treatment were incubated for 24 hours, after which they were exposed to radiation doses of 2, 3, and 4 Gy. After irradiation, the cells were incubated for an additional 24 and 48 hours. Following the incubation periods, cell viability was assessed using the MTT method. To minimize potential bias in interpreting data regarding the radioprotective effects of the Q. brantii extract, the dose and timing of ionizing radiation were selected such that the percentage of surviving cells could be reduced to approximately 50% of the control group (cells not exposed to radiation or any treatment).

3.5. Evaluating the Effect of Different Concentrations of Quercus brantii Extract on Cells Without Radiation Exposure

After 24 hours of incubation, the plates intended for Q. brantii extract treatment were taken out, and concentrations of 10, 25, 50, 75, and 100 μg/mL of the extract were added to the wells. The plates were then incubated for an additional 48 hours, after which cell viability was assessed using the MTT method.

3.6. Evaluating the Viability of HT29 Cells Irradiated with a Toxic Dose of Radiation in the Presence and Absence of Quercus brantii Extract

After 24 hours, the respective plates were removed from the incubator, and one plate was treated with a concentration of 10 μg/mL of extract. Then, both plates were irradiated with 4 Gy. Cell viability was subsequently evaluated using the MTT method.

3.7. Evaluating the Duration Needed for Quercus brantii Extract to Take Effect Prior to Radiation Exposure

Following 24 hours of incubation, the respective plates were treated with the optimal concentration of Q. brantii extract at intervals of 60, 105, and 150 minutes before radiation exposure. Radiation was then applied at a dose of 4 Gy, which was determined based on preliminary experiments to reduce HT29 cell viability to approximately 50% of the control cells. Following irradiation, cells were incubated for an additional 48 hours, and cell viability was evaluated using the MTT assay.

3.8. Evaluating the Effect of Different Concentrations of Quercus brantii Extract Prior to Radiation Exposure of 4 Gy

After 24 hours of incubation, the respective plates were treated with various concentrations of Q. brantii extract. They were then maintained in the incubator for 105 minutes before being subjected to 4 Gy of radiation. Following radiation, the cells were incubated for another 48 hours. The MTT method was utilized to assess cell viability, and the percentage of viable cells was calculated.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

The data were stated as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (SPSS Inc, Chicago IL, USA), and the graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a t-test with two independent samples were used for data analysis. Post-hoc comparisons following ANOVA were conducted using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test to determine pairwise group differences. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Assessment of the Viability of HT29 Cells to Radiation

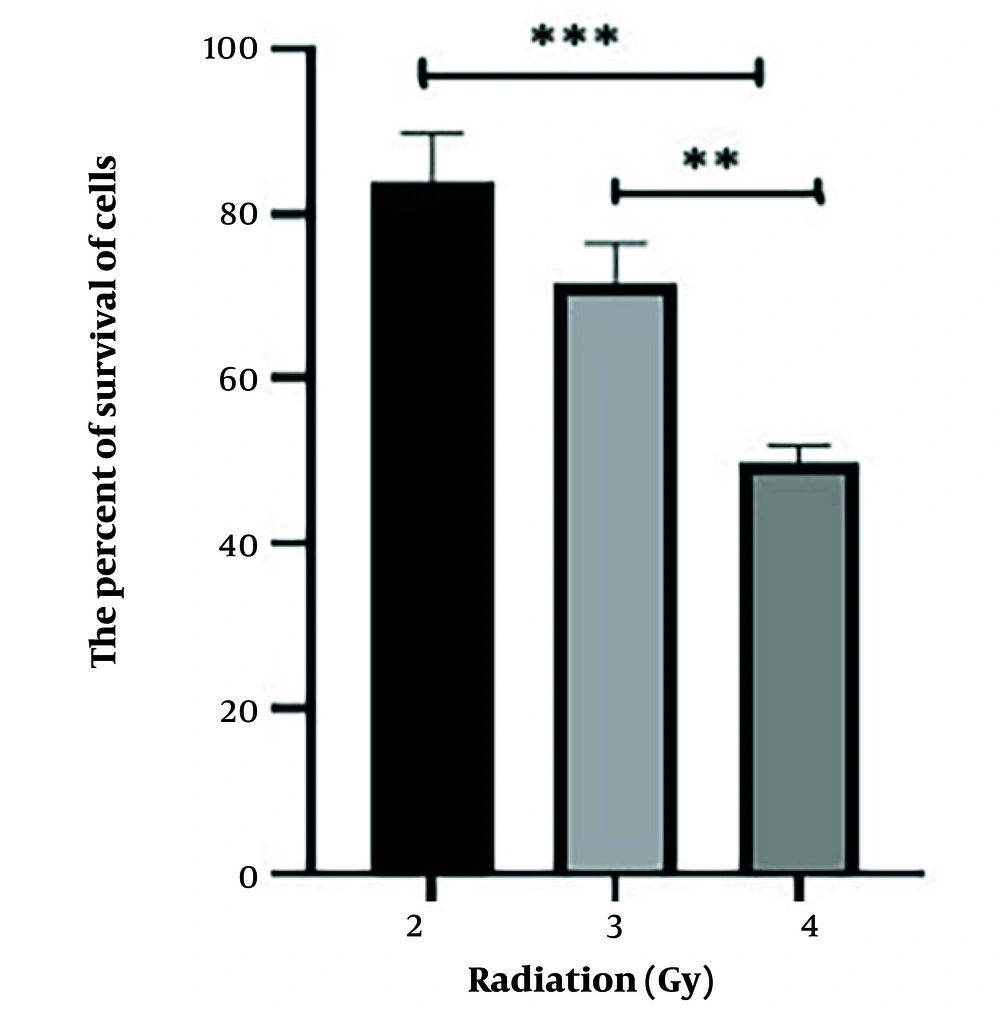

As shown in Table 1, the percentage of survival of the HT29 cells was reduced to approximately 50% of the control cells when the dose of ionizing radiation was 4 Gy, and radiation was carried out 48 hours after the harvesting of the HT29 cells in the 96-well plates. Based on the cell viability data presented in Table 1, a dose-response curve was constructed to evaluate the effect of ionizing radiation on HT29 cells at 48 hours post-irradiation. Figure 1 demonstrates a dose-dependent decline in cell viability, with survival rates decreasing from approximately 83.7% at 2 Gy to 49.7% at 4 Gy.

| Radiation (Gy) | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 79 ± 7.21 | 75 ± 2.65 | 69.67 ± 9.5 |

| 48 h | 83.67 ± 6 | 71.67 ± 4.73 | 49.67 ± 2.31 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

b The different doses of radiation were applied up to 48 hours after seeding the HT29 cells on the 96-well plate (n = 3).

c The percentage of survival cells was calculated by dividing the absorbance of treated cells by control cells.

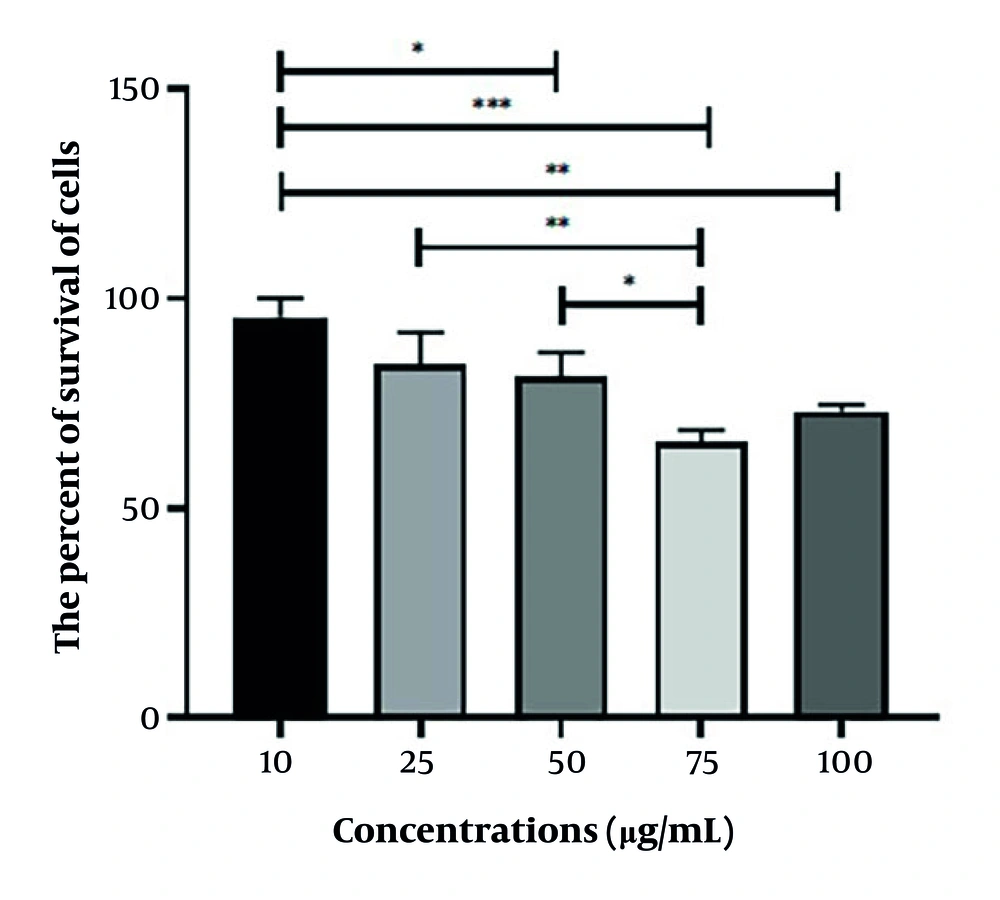

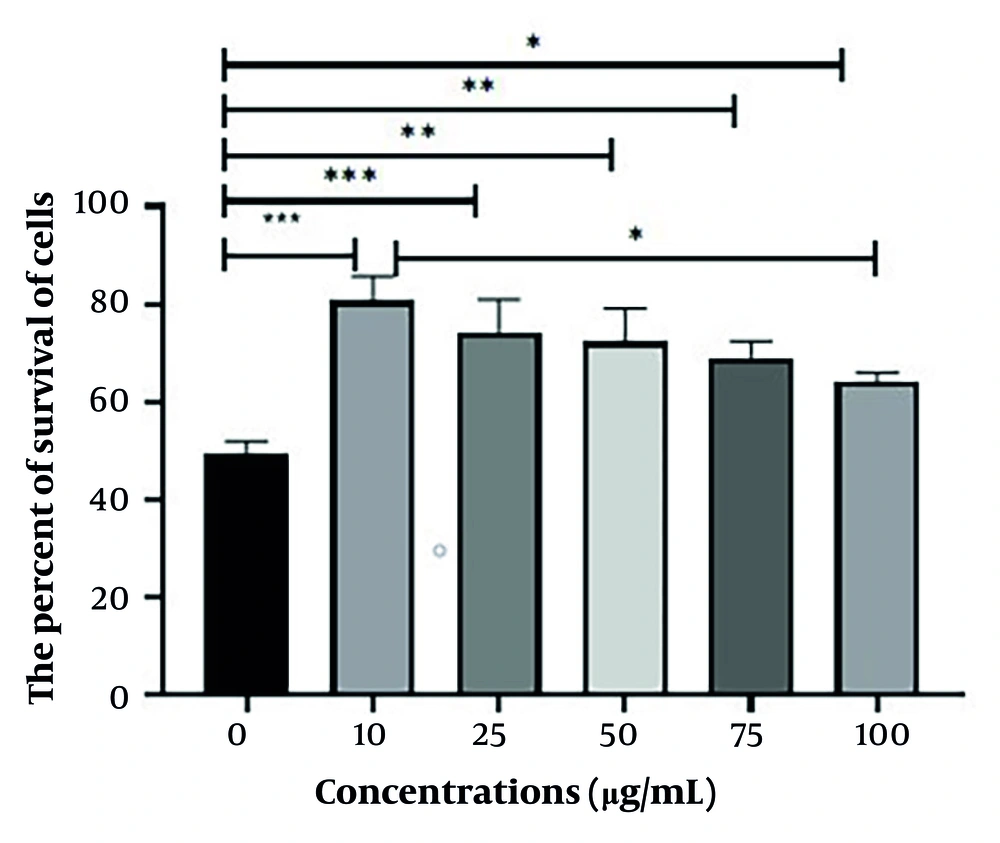

4.2. Assessment of the Viability of HT29 Cells in Different Doses of Quercus brantii Extract

The data presented in Figure 2 indicate that cell survival is higher at a concentration of 10 μg/mL of the extract than that observed at other concentrations.

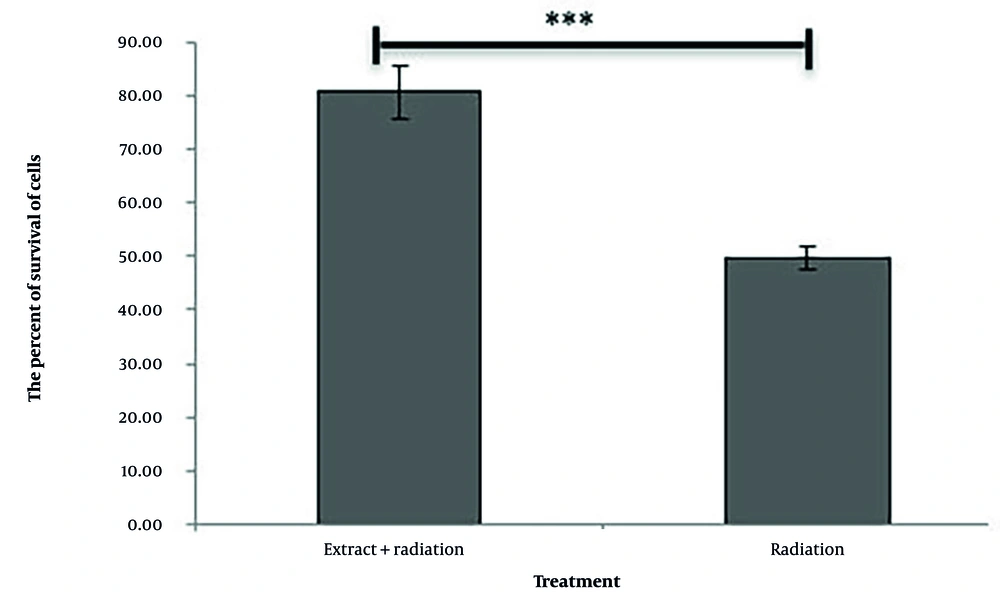

4.3. Assessment of the Viability of HT29 Cells with a Combination of the Plant Extract and Ionizing Radiation

As shown in Figure 3, the cell viability in the group treated with a combination of 10 μg/mL of the extract and 4 Gy of radiation is significantly higher than that in the group treated with 4 Gy of radiation alone (P < 0.001).

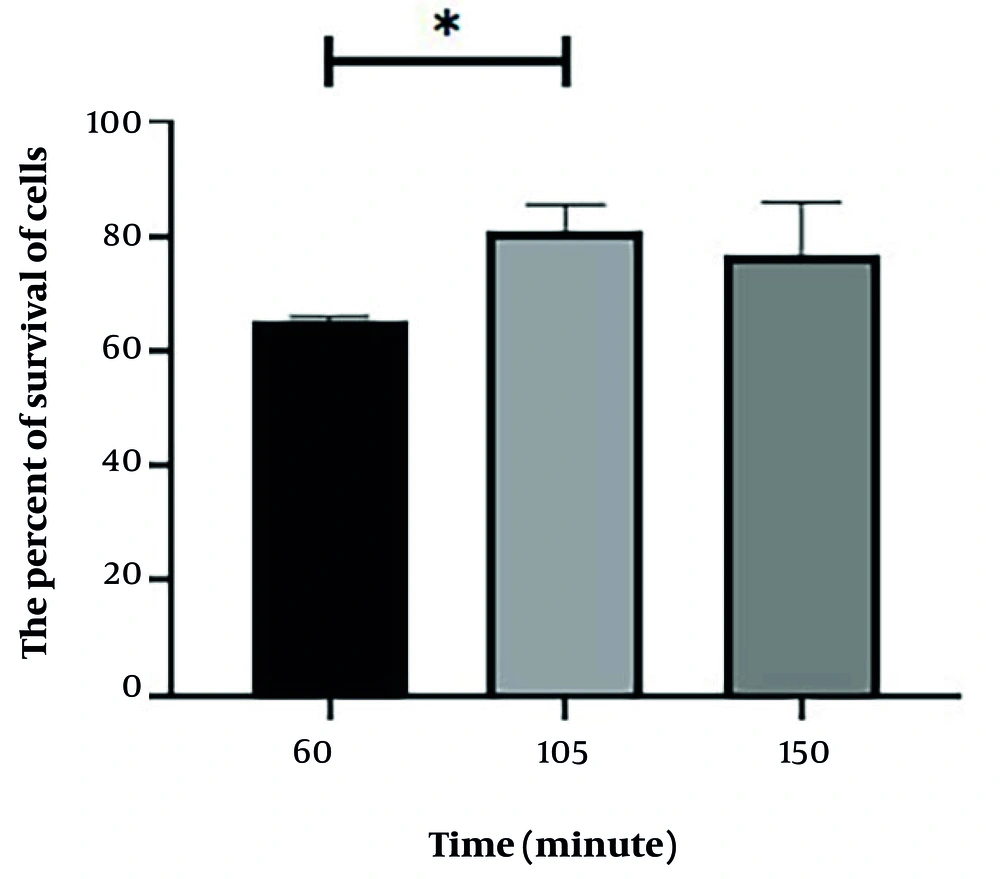

4.4. Assessment of the Viability of HT29 Cells with Quercus brantii Extract at Different Times Before Ionizing Radiation

The data presented in Figure 4 demonstrate that the highest level of radioprotection activity occurred when the plant extract was administered 105 minutes prior to exposure to radiation.

4.5. Assessment of the Effect of Different Concentrations of Quercus brantii Extract Prior to Radiation Exposure of 4 Gy

As illustrated in Figure 5, the radioprotective effect on the treated cells 105 minutes before being irradiated with 4 Gy has been observed at concentrations ranging from 0 µg/mL to 100 µg/mL of the plant extract. While different doses of Q. brantii extract demonstrated significant radioprotective effects, the concentration of 10 µg/mL exhibited the highest level of radioprotection.

5. Discussion

Ionizing radiation induces cellular damage primarily through direct ionization of biomolecules and indirectly via the generation of free radicals, predominantly targeting DNA (21, 22). While cells employ various defense mechanisms, such as antioxidant enzymes (catalase, glutathione peroxidase, superoxide dismutase) to counteract this damage, the role of exogenous radioprotective agents is crucial in mitigating radiation-induced cytotoxicity (23, 24). The proposed mechanisms of action for radioprotective compounds include the neutralization of free radical species by donating electrons, reducing the generation of ROS, enhancing the function of antioxidant enzymes, and promoting the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells (25, 26).

Recent literature emphasizes the potential of plant-based radioprotectors, particularly due to their antioxidant properties, low toxicity, and accessibility. Flavonoids, prevalent polyphenolic compounds found in plants such as Q. brantii, exhibit strong free radical scavenging effects, which are essential in reducing radiation-induced oxidative damage (17, 27, 28). Our findings reveal a significant radioprotective effect of Q. brantii extract on HT29 cells, consistent with earlier studies on plant-derived flavonoids. For instance, Shimoi et al. demonstrated substantial radioprotection in mice models through flavonoid-induced free radical scavenging (29), while Devi et al. similarly observed chromosomal protection by orientin and vicenin flavonoids in irradiated mice (30). Additionally, studies by Shourmij et al. have highlighted the significant anti-cancer effects of Q. brantii in human breast cancer cells, underscoring its potential as a novel therapeutic agent (31). This multifaceted action positions Q. brantii not merely as a radioprotective agent but as an innovative candidate for cancer treatment strategies, warranting further investigation into its therapeutic mechanisms and applications.

Importantly, our methodological approach involved a stepwise evaluation beginning with the assessment of radiation doses to establish a toxic dose that reduces cell viability by approximately 50% (section 2.4), followed by testing the cytotoxicity of different concentrations of Q. brantii extract in the absence of radiation (section 2.5). The combined effect of the extract at a selected concentration with radiation was then analyzed to identify the radioprotective potential (section 2.6). Subsequently, we focused on determining the optimal pre-treatment timing of the extract before radiation exposure (section 2.7). Building on these findings, we re-examined the dose-dependent radioprotective effects specifically at the optimal timing identified (105 minutes before irradiation) by testing different concentrations once again (section 2.8). This comprehensive and sequential evaluation of dose and timing effects allowed us to thoroughly characterize the radioprotective efficacy of Q. brantii extract, ensuring robust and reliable conclusions with respect to both concentration and temporal parameters.

The innovative aspect of our study lies in the systematic and integrated evaluation of both concentration and timing parameters in assessing the radioprotective effects of Q. brantii extract. Unlike previous studies, our stepwise methodology offers a comprehensive characterization of how optimal dosing and pre-treatment timing influence radioprotection.

In considering the radioprotective effects of Q. brantii, it is important to contextualize these findings within the broader landscape of existing natural and synthetic radioprotective agents. While our study demonstrates significant protective effects, further comparative analyses with well-established compounds, such as curcumin, catechins, and synthetic radioprotectors like amifostine, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of Q. brantii's efficacy. This comparative framework will help delineate its unique mechanisms and potential advantages, thereby better informing future research and therapeutic applications in radioprotection. Nevertheless, our findings serve as a promising foundation for exploring Q. brantii's role in mitigating radiation-induced cellular damage.

It is important to acknowledge that this study exclusively utilized the MTT assay to assess cellular viability. Therefore, future studies incorporating molecular assays such as qPCR, Western blotting, or ROS measurements are essential to further elucidate the precise mechanisms underlying the radioprotective effects of Q. brantii and to validate the findings presented here.

5.1. Conclusions

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that Q. brantii extract at a concentration of 10 µg/mL exhibits significant radioprotective effects on HT29 cells, effectively enhancing cell viability without inducing cytotoxicity. The optimal radioprotection was achieved when the extract was administered 105 minutes prior to exposure to ionizing radiation. These promising in vitro findings suggest that Q. brantii has potential as a natural radioprotective agent. However, given the limitations inherent in our experimental design — including the use of a single cell line and in vitro conditions — comprehensive in vivo investigations and clinical trials are essential to confirm safety, efficacy, and optimal dosing strategies. Furthermore, elucidating the underlying molecular mechanisms will provide valuable insight into its therapeutic potential. Ultimately, this work lays the foundation for future studies aimed at developing Q. brantii as a complementary adjunct to RT, potentially improving treatment outcomes and reducing radiation-induced side effects in cancer patients.