1. Context

The tonsils are the largest part of the body's defense system and are located at the heart of the mucosal lymphoid tissue complex located in the mouth, pharynx, and nasal cavities (1). Tonsils produce lymphocytes and plasma cells, among which T lymphocytes are responsible for cellular immunity and immunoglobulins (IgA, IgE, and IgM), and B lymphocytes are responsible for humoral defense (2). Tonsillar crypts are small, pit-like structures in the tonsil tissue that increase the surface area for antigen contact and facilitate the drainage of secretions into the oral cavity. Thus, the tonsils play an important role in local and systemic immunity (2). This process is continued due to the special structure of the tonsils and intense contact with antigen cells in the oral cavity (1). As long as these crypts drain easily into the oral cavity, the function of the tonsils is not compromised. However, if physiological contents remain in these crypts due to anatomical narrowing or infection, an ideal environment is provided for the growth of microorganisms. This leads to the formation of bacterial or fungal colonies and, ultimately, can lead to chronic suppuration, small abscesses in the crypts, and ulceration of their surface (3, 4). However, the tonsils become a focus of infection, which causes symptoms such as swollen tonsils, severe fever and chills, a burning sensation in the throat, persistent pain in the oropharynx, and pain during swallowing and earache (5, 6).

On the other hand, due to the location of the tonsils in the nasopharynx and their abnormal increase in volume, they can lead to narrowing of the respiratory and digestive tracts, increasing the risk of developing problems such as obstructive sleep apnea (1). In such situations, the decision to remove the tonsils is considered a necessary treatment option, despite the unwanted risks it can pose to the immune system. Chronic tonsillitis often does not respond to non-surgical treatments such as gargling and suctioning, and the limited effects of antibiotics only last for the duration of treatment. (7, 8). So that when the drug is discontinued, the pathological mechanisms are reactivated, because the anatomical conditions of the area will not change. Therefore, the surgical method of tonsillectomy is proposed as the only effective option for the treatment of this disease (9). Tonsillectomy surgery is performed by otolaryngologists. Despite its apparent simplicity, it can cause significant side effects, including pain, bleeding, and nausea (10). Postoperative bleeding is one of the most common complications of tonsillectomy, which can occur in two distinct phases, primary and secondary. This complication can not only increase hospital costs but also be a painful and unpleasant experience for the patient (11).

2. Objectives

Considering the various studies conducted in the world aiming to investigate the prevalence of bleeding and its control methods after tonsillectomy, conducting a comprehensive study that compiles all the results of the studies in one study is of particular importance. This measure can pave the way for health planning and health-related policies. Also, identifying effective factors related to the control of bleeding after tonsillectomy can provide conditions for medical and environmental interventions and reduce the prevalence of bleeding after tonsillectomy.

3. Methods

This study was conducted as a systematic review, and articles published online in the databases Scopus, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, Magiran, SID, and Irandoc were reviewed. A search for the prevalence of bleeding after tonsillectomy was conducted using the keywords "prevalence", "tonsillectomy", and "bleeding". The inclusion criteria for studies at this stage were English or Persian language with an English abstract, publication year 2019 - 2024, and a target population of children or adults. Interventional, comparative, and studies that were not available in their full text, or whose sample size was less than 10 people, were excluded from the study. Bleeding after tonsillectomy was considered an outcome.

Second stage: To identify factors associated with bleeding after tonsillectomy, the PubMed MeSH database was searched using the keywords "tonsillectomy", "bleeding", and "risk factor" and the operators "AND", "OR". The inclusion criteria for studies were English or Persian language with an English abstract, publication year 2019 - 2024, and a target population of children or adults. Studies that were not available in their full text or whose sample size was less than 10 people were excluded from the study. Factors associated with bleeding after tonsillectomy were considered as an outcome.

Studies were extracted in both stages using EndNote version 21. Extracted articles were aggregated in each database in EndNote. Duplicate articles were removed, and irrelevant articles or articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were assessed based on the title and abstract. Then, the quality of the studies was assessed by two reviewers using the STROBE tool.

The STROBE statement includes sections such as title and abstract, introduction and methods, results, discussion and conclusion, and other information. In the scoring, sufficient reference to the content of each item was given a score of one, and no reference was given a score of zero. The total score of the checklist in this study was 34. The distribution of scores by section was as follows: Title and abstract 2 scores, introduction 2 points, materials and methods 14 scores, results 11 scores, discussion 4 scores, and other information 1 score. The reviewed articles were divided into four categories of very good quality (score higher than 28), good (score 27 - 18), moderate (score 18 - 10), and poor (score less than 9) based on the checklist scores. Studies with poor quality according to the STROBE criteria were excluded. Disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

The STROBE statement includes the sections of title and abstract, introduction and methods, findings, discussion and conclusion, and other information. In scoring, sufficient reference to the content of each item was given a score of one, and no reference was given a score of zero. The total score of the checklist in this study was 34. The distribution of scores was as follows, according to the number of independent items in each section. Title and abstract were given 2 scores, introduction 2 scores, materials and methods 14 scores, findings 11 scores, discussion 4 scores, and other information 1 score. The reviewed articles were divided into 3 categories of good, moderate, and poor-quality articles based on the scores obtained from the checklist. Studies that received a score of more than 25 were classified as good quality, 10 - 25 as moderate quality, and poor quality as scores less than 9 and below.

4. Results

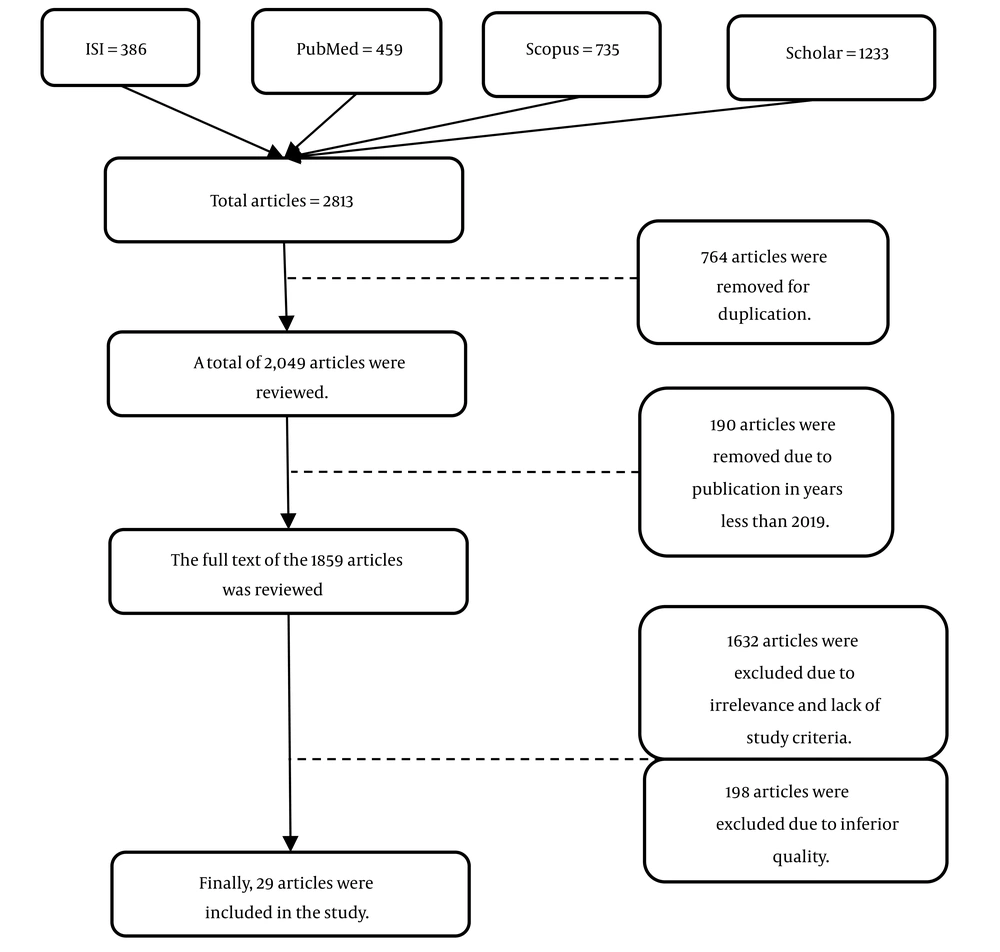

Based on the results of the article search, 1680 studies were found for prevalence, of which 29 studies were eligible for inclusion based on the criteria of the present study. The process of evaluating the studies was reported in algorithm 1. The study type was conducted in 4 articles as a prospective cohort, 20 articles as a retrospective cohort, and 5 studies as a descriptive-cross-sectional study. The quality of 11 of the 29 articles was very good, 14 articles were good, and 4 articles were moderate according to the STROBE criteria. The population and sample size for reporting the prevalence/incidence of post-tonsillectomy bleeding are described in Table 1 and Figure 1.

| Authors (y) | Reference | Study Type | Sample Size | Statistical Population (y) | Prevalence of Bleeding After Tonsillectomy (%) | Incidence (%) | Article Quality | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Total | |||||||

| Bofares and Halen (2021) | (12) | Prospective | 2880 | 8 mo - 85 | 22 | 71 | Not reported | - | Good |

| Lloyd et al. (2021) | (13) | Retrospective | 14152 | Children | Not reported | Not reported | 83.3 | - | Very good |

| Smith et al. (2022) | (14) | Retrospective | 829 | Child < 18 | Not reported | Not reported | 6 | - | Very good |

| Tanaka et al. (2021) | (15) | Retrospective | 497 | 3 - 86 | Not reported | Not reported | 7 | - | Good |

| Raza et al. (2023) | (16) | Cross-sectional | 66 | 3 - 18 | - | - | - | 15.2 | Good |

| Xu et al. (2021) | (17) | Retrospective | 1505 | 2 - 18 | 33.7 | 66.3 | Not reported | - | Very good |

| Arif et al. (2025) | (18) | Prospective | 287 | 4 - 40 | - | 5.9 | Not reported | - | Good |

| Taylor (2022) | (19) | Retrospective | 219 | 1 - 45 | 41 | 59 | Not reported | - | Good |

| Juul et al. (2020) | (20) | Retrospective | 177211 | 1 - 40 | 12 | Not reported | 5.2 | - | Good |

| Hazir et al. (2024) | (21) | Case-control | 1137 | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 5.72 | - | Average |

| Noy et al. (2023) | (22) | Retrospective cohort | 274 | 18 - 82 | 2 | 15.7 | 7 | - | Good |

| Aldrees et al. (2022) | (23) | Retrospective | 713 | 1 - 13 | Not reported | Not reported | 5.3 | - | Good |

| Archer et al. (2020) | (24) | Retrospective | 14951 | Child < 22 | Not reported | Not reported | 3.9 | - | Very good |

| Keltie et al. (2021) | (25) | Retrospective cohort | 318453 | Child < 16 | Not reported | Not reported | 1.3 | - | Very good |

| Asulin et al. (2024) | (26) | Retrospective cohort | 1026 | 1 - 18 | Not reported | Not reported | 9.5 | - | Very good |

| Besiashvili et al. (2024) | (27) | Cross-sectional | 778 | Adults > 18 | 8.1 | 6.6 | 14.7 | - | Very good |

| Spencer et al. (2022) | (28) | Retrospective | 1428 | Children and adults | - | - | - | 5.7 | Good |

| Slouka et al. (2021) | (29) | Retrospective cohort | 2842 | Adults (20 - 50) | Not reported | Not reported | 10.03 | - | Good |

| Mohamed et al. (2022) | (30) | Prospective | 60 | Child < 14 | - | - | - | 5 | Good |

| Alsalamah et al. (2024) | (31) | Retrospective cohort | 1282 | Child < 18 | - | - | - | 49.4 | Very good |

| Abdel Rahman et al. (2019) | (32) | Prospective | 1200 | Mean 13.53 | 33.3 | 66.6 | Not reported | - | Good |

| Tripathi et al. (2021) | (33) | Cross-sectional | 193 | Children and adults | Not reported | Not reported | 18.5 | - | Very good |

| Dilber and Salcan (2021) | (34) | Retrospective | 634 | 7 - 40 | Not reported | Not reported | 20.5 | - | Good |

| Attard and Carney (2020) | (35) | Cohort 10-y | 608 | Child < 16 | - | - | - | 8.3 | Average |

| Hsueh et al. (2019) | (36) | Cohort 15-y | 27365 | Adults | - | - | - | 10.2 | Very good |

| Chorney et al. (2021) | (37) | Cross-sectional | 250 | Children | Not reported | Not reported | 78 | - | Average |

| Taziki et al. (2020) | (38) | Cross-sectional | 1043 | Children and adults | 54.5 | 81.8 | Not reported | - | Average |

| Inuzuka et al. (2020) | (39) | Retrospective | 325 | Adults | 21.8 | 1.5 | Not reported | - | Good |

| Alsala et al. (2024) | (40) | Retrospective cohort | 1280 | Child < 18 | 3.4 | Not reported | Not reported | - | Very good |

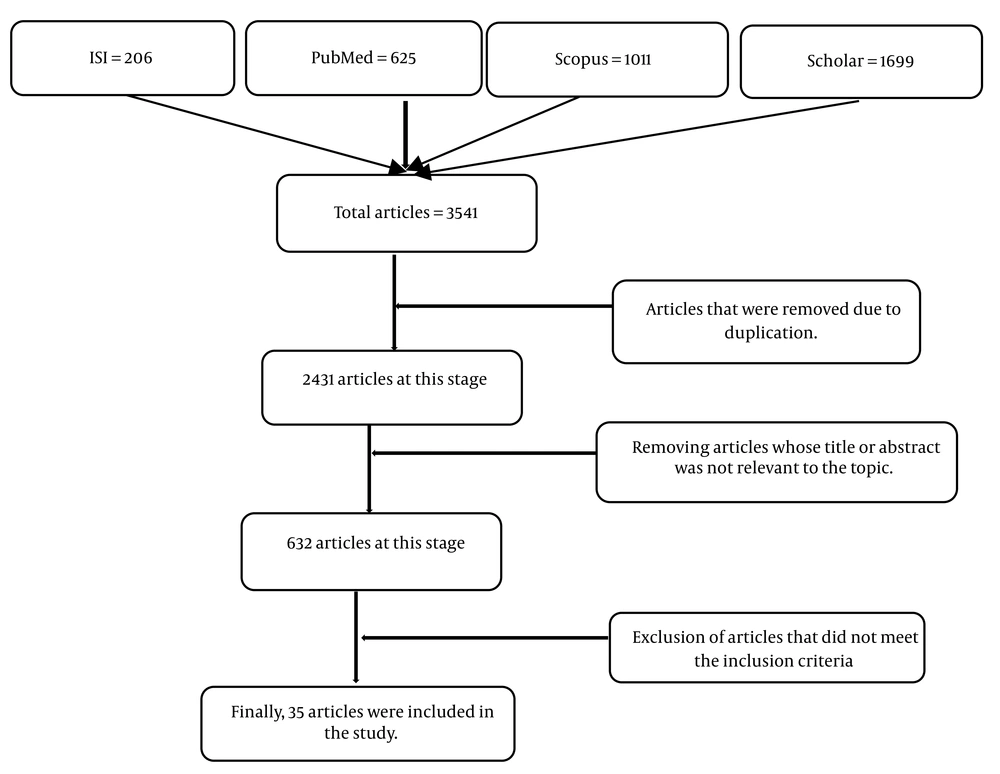

Based on the search results, 3541 studies were found on factors related to the control of bleeding after tonsillectomy, of which 35 studies met the inclusion criteria for the present study. The process of evaluating studies and selecting articles was described in algorithm 2. Nine articles were clinical trials, 3 articles were case-control studies, and the remaining studies were cohort and cross-sectional. The quality of 25 of the 35 articles was very good, 9 articles were good, and 1 article was moderate (Table 2 and Figure 2).

| Authors (y) | Reference | Study Type | Sample Size | Statistical Population (y) | Group 1 | Index | Group 2 | Index | Description | Article Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mane and Gavali (2024) | (41) | Prospective observational | 200 | Lower pole silk ligation | - | Pillar suturing technique | - | The pillar suturing technique showed a statistically significant reduction in primary and secondary bleeding after tonsillectomy compared with lower pole silk ligation. | Very good | |

| Patel et al. (2019) | (42) | Retrospective cohort | 1085 | 1 - 18 | A total of 132 individuals received intravenous ibuprofen. | Prevalence: 0.7% | 953 individuals did not receive intravenous ibuprofen. | Prevalence: 0.1% | The amount of bleeding observed in patients who received intravenous ibuprofen was not statistically different from that in patients who did not receive the drug. | Very good |

| Mattheeuws et al. (2019) | (43) | Retrospective | 957 | 524 (adults), 433 (child) | Dexamethasone, a corticosteroid anti-inflammatory drug | Prevalence: 1.5% | - | - | The medications used did not affect the degree of bleeding control. | Very good |

| Oflaz Caparet al. (2024) | (44) | Prospective | 41 | 5 - 10 | Injection of 1 cc PRF | - | - | - | The medications used did not affect the degree of bleeding control. | Good |

| Li (2024) | (45) | Clinical trial | 68 | 34 (case), 34 (control) | Lidocaine local anesthetic injection | - | Epinephrine local anesthetic injection | - | The local injection of epinephrine and lidocaine reduced bleeding compared to using epinephrine alone. | Very good |

| Miller et al. (2021) | (46) | Retrospective cohort | 4098 | 2 - 18 (Groups A and B) | Ibuprofen | - | No ibuprofen | - | No difference in bleeding after tonsillectomy was observed between patients who used ibuprofen and patients who did not receive the drug. | Very good |

| Tierney et al. (2024) | (47) | Single-blind clinical trial | 61 | Adults | Undergoing surgery with BiZact technique | - | Undergoing surgery with coblation technique | - | The BiZact group had a longer time to achieve hemostasis and had more intraoperative blood loss. | Very good |

| Abdelsalam et al. (2023) | (48) | Retrospective (comparative) | 100 | Child < 12 | BiZact technique | Prevalence: 4.0% | Cold steel method | Prevalence: 20.0% | The new BiZact technology was superior to the cold steel method in tonsillectomy with minimal bleeding. | Good |

| Ashraf et al. (2022) | (49) | Clinical trial | 60 (4 years -45 years) | (Groups A and B) | Receiving tranexamic acid | Mean blood loss: 30.27 mL | Control | Mean blood loss: 67.67 mL | The mean bleeding rate was significantly lower in subjects receiving tranexamic acid compared to the control group. | Very good |

| Faramarzi et al. (2021) | (50) | Double-blind clinical trial | 240 | 3 - 18 | Celecoxib | Prevalence: 1.0% | Acetaminophen | Prevalence: 0.0% | The two groups had no statistical difference in bleeding after tonsillectomy. | Good |

| Masood et al. (2021) | (51) | Clinical trial | 60 | 6 - 20 | Adrenaline injection with tramadol | Mean time required for hemostasis: 4.2 min | Normal saline injection | Mean time required for hemostasis: 5.7 min | Injection of adrenaline combined with tramadol during tonsillectomy resulted in a significant reduction in postoperative bleeding and pain compared to normal saline injection. | Very good |

| Saleh and Rabie (2021) | (52) | Prospective | 60 | > 21 | One 500 mg Daflon tablet | Prevalence: 7.0% | Hospital protocol | Prevalence: 13.3% | Using Daflon 500 mg tablets after tonsillectomy can help reduce the amount and severity of bleeding. | Very good |

| So et al. (2024) | (53) | Retrospective cohort | 4996 | Child < 18 | Celecoxib | Prevalence: 1.9% | No celecoxib | Prevalence: 1.6% | The medications used did not affect the degree of bleeding control. | Good |

| Kolb et al. (2021) | (54) | Retrospective cohort | 1920 | Child < 19 | 1452 children received ketorolac | Prevalence: 1.4% | 462 did not | Prevalence: 1.7% | The two groups had no statistical difference in bleeding after tonsillectomy. | Very good |

| Shaikh et al. (2024) | (55) | Retrospective cohort | 307716 | Child < 18 | 17434 children received ketorolac | - | 290373 children did not receive ketorolac | - | The use of ketorolac was associated with an increased risk of primary and secondary postoperative bleeding requiring surgery. | Good |

| Stevens et al. (2022) | (56) | Retrospective (case-control) | 1416 | Mean = 5 | 712 people received oral steroids | Prevalence: 1.8% | 704 people did not use oral steroids. | Prevalence: 3.1% | Oral steroids were safe after surgery and did not increase the risk of bleeding after tonsillectomy in children. | Very good |

| Trombetta et al. (2024) | (57) | Cohort | 4744 | Child < 18 | 2598 children undergoing tonsillectomy/added to gauze swab | Prevalence: 1.4% | Control group did not receive | Prevalence: 2.6% | A reduction in bleeding was observed in the treatment group. | Very good |

| Thejas et al. (2021) | (58) | Case-control | 133 | 6 - 30 | Case group: 3% hydrogen peroxide | Blood loss volume, mean: 47.4 mL | Control group did not receive | Blood loss volume, mean: 56.5 mL | Using 3% hydrogen peroxide in moderation is very effective in preventing blood loss. | Very good |

| Mohamed et al. (2022) | (30) | Prospective | 60 | > 14 | 30 patients who underwent TE coblation with intraoperative suture | Prevalence: 0.0% | 30 patients who underwent coblation tonsillectomy without intraoperative sutures. | Prevalence: 10.0% | Coblation with sutures was better than coblation without sutures. This method was associated with low postoperative bleeding. | Average |

| Feldman et al. (2024) | (59) | Retrospective | 4694 | Child < 18 | Receiving ketorolac | Prevalence: 1.9% | Not receiving ketorolac | Prevalence: 1.6% | There was no association between postoperative ketorolac administration and bleeding control. | Good |

| Rabbani et al. (2020) | (60) | Retrospective cohort | 1322 | Child < 18 | 669 receiving ketorolac | Prevalence: 6.5% | 653 not receiving ketorolac | Prevalence: 5.3% | Ketorolac did not increase the risk of bleeding following tonsillectomy. | Very good |

| Hsieh et al. (2022) | (61) | Prospective | 60 | 8 - 68 | Receiving hydrogen peroxide | Blood loss volume, mean: 9.9 mL | Receiving adrenaline | Blood loss volume, mean: 13.8 mL | Hydrogen peroxide can be used as a routine hemostatic agent to control bleeding in tonsillectomy surgery. | Very good |

| McClain et al. (2020) | (62) | Retrospective cohort | 263 | > 18 | Receiving ketorolac | Prevalence: 58.0% | Not receiving ketorolac | Prevalence: 66.0% | The two groups had no statistical difference in bleeding after tonsillectomy. | Good |

| Bae et al. (2020) | (63) | Prospective | 40 | Child < 15 | Receiving filmogen topical spray | Prevalence: 4.7% | Not receiving filmogen topical spray | Prevalence: 5.3% | Topical filmogen spray is not effective for controlling bleeding in the tonsil area. | Very good |

| Rosi-Schum et al. (2024) | (64) | Case-control | 199 | 56 receiving intravenous ibuprofen | Prevalence: 19.6% | 143 not receiving intravenous ibuprofen | Prevalence: 7.7% | Bleeding after tonsillectomy was reduced with a dose of 400 mg of ibuprofen postoperatively. | Good | |

| Bal (2022) | (65) | Clinical trial | 107 | 18 - 88 | 54 patients on tranexamic acid | Blood factors | 53 patients without tranexamic acid | Blood factors | Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss. | Very good |

| Awad et al. (2021) | (66) | Retrospective | 8 | 3 - 9 | N-butyl 2- cyanoacrylate (butyl cyanoacrylate adhesive) | - | - | - | The adhesive was effective in controlling bleeding. | Good |

| Zhang et al. (2020) | (67) | Retrospective | 5087 | 18 - 49 | Case group (suture) | Prevalence: 1.9% | Control group (without suture) | Prevalence: 1.1% | Secondary bleeding rates were lower in patients with sutures. | Very good |

| Faramarzi et al. (2021) | (68) | Prospective | 60 | Using amniotic membrane as a dressing | Prevalence: 6.4% | Control | Prevalence: 3.4% | This method did not affect controlling bleeding. | Very good | |

| Ghadami et al. (2022) | (69) | Clinical trial | 109 | 5 - 18 | 40 mg of 1% lidocaine and 5 micrograms of epinephrine | Blood loss volume, mean: 65.5 mL | Control group (without lidocaine-epinephrine administration) | Blood loss volume, mean: 113.7 mL | Administration of lidocaine-epinephrine reduced bleeding. | Very good |

| Kolesnichenko (2023) | (70) | Clinical trial | 158 | 97 patients underwent tonsillectomy using local anesthesia | Blood loss volume, mean: 60.1 mL | 61 patients underwent tonsillectomy using tracheal anesthesia. | Blood loss volume, mean: 77.2 mL | Tonsillectomy with local anesthesia had less blood loss. | Very good | |

| Smith et al. (2020) | (71) | Retrospective (case-control) | 260 | Child < 16 | 195 patients on tranexamic acid | Prevalence: 13.0% | 65 patients without tranexamic acid | Prevalence: 23.0% | This method did not affect controlling bleeding. | Very good |

| Abtahi et al. (2023) | (72) | Double-blind clinical trial | 20 | 15 - 45 | 10 patients on tranexamic acid | Blood loss volume, mean: 87.5 mL | 10 people placebo | Blood loss volume, mean:92.5 mL | Tranexamic acid was not superior to placebo in controlling bleeding. | Very good |

| Yadav et al. (2023) | (73) | Retrospective | 103 | 18 - 58 | Receiving ketorolac | Prevalence: 11.1% | Not receiving ketorolac | Prevalence: 19.0% | Ketorolac is not associated with an increased risk of bleeding after tonsillectomy in children and can be prescribed. | Very good |

Abbreviation: PRF, platelet-rich fibrin.

A review of 29 studies showed that the overall prevalence of post-tonsillectomy bleeding was reported as 83% (14,152 children) in the study by Lloyd et al. (13) and 78% (250 children) in the study by Chorney et al. Among 1,045 children and adults, the prevalence of primary and secondary bleeding after tonsillectomy was 54.5% and 81.8%, respectively. Overall, the incidence rate of post-tonsillectomy bleeding in children < 18 was reported to be 49.9% (37).

Based on the literature search, the study by Abdelsalam et al. showed that the cold steel method and BiZact method caused post-tonsillectomy bleeding at a rate of 20.0% and 4.0%, respectively (48). Therefore, BiZact method is more effective in reducing post-tonsillectomy bleeding. The study by Saleh and Rabie showed that the prevalence of post-tonsillectomy bleeding in people > 21 years was 7.0% in the group using Daflon 500 mg and 13.3% in the group using the hospital protocol. According to the study by Kolb et al., the prevalence of post-tonsillectomy bleeding was reported to be 1.4% in children < 19 years who used ketorolac and 1.7% in children who did not use it (54).

5. Discussion

The results of the review of studies showed that the highest overall prevalence of bleeding after tonsillectomy was related to the retrospective cohort study of Lloyd et al. (2021) with a prevalence of 83.3% in 14,152 children over 8 years (13) and a cross-sectional study of Chorney et al. (2021) with a prevalence of 78.0% in 250 children over 5 years (37). However, the lowest overall prevalence was reported in a retrospective cohort study by Keltie et al. (2021) in 318,453 children under 16 years of age, at 1.3% (25). On the other hand, the prevalence of primary bleeding after tonsillectomy ranged from 0.2% to 54.5% and the prevalence of secondary bleeding ranged from 1.5% to 81.8% in studies. The difference in prevalence in different studies may be due to the location of the study, the statistical population, the type of hospital (private, public), or the sampling method. Also, failure to observe pre- and post-tonsillectomy care in patients affects bleeding after tonsillectomy. Because pre- and post-tonsillectomy care plays an important role in the success of the operation, and in reducing possible complications. By observing this care, it can help the wound heal faster and prevent subsequent problems.

The results showed that using the BiZact technique for surgery was associated with less bleeding than using the Coblation technique. The BiZact Tonsillectomy Device was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for use in tonsillectomy procedures for secondary bleeding (47, 48). Also, the Pillar Suturing surgical technique showed a statistically significant reduction in primary and secondary bleeding after tonsillectomy compared to the lower pole silk ligation method (41). Pillar suturing involves suturing the tissues of the tonsil wall, especially at the sides of the tonsil base and the junction between the layers, in order to reduce or stop blood flow after tonsil removal. In lower pole silk ligation, coughing or vomiting can cause the knot to loosen and become untied, resulting in secondary bleeding. Therefore, the pillar suturing technique reduces complications such as pain and bleeding after tonsillectomy. The results of these studies indicate that the experience of the ENT surgeon in the field of suturing, or not, and the method of suturing, help to reduce bleeding after tonsillectomy. Therefore, it is recommended that more studies be conducted in this field.

The results of the present study showed that the use of hydrogen peroxide, Daflon tablets, adrenaline injection with tramadol, and lidocaine-epinephrine in different statistical populations reduced the amount and severity of bleeding after tonsillectomy. A pilot study by Masood et al. (2021) on 60 people aged 6 to 20 years showed that injection of adrenaline along with tramadol during tonsillectomy resulted in a significant reduction in postoperative bleeding and pain compared to injection of normal saline (51). A prospective study by Saleh and Rabie (2021) was conducted on 60 people over 21 years of age, and the results showed that taking 500 mg Daflon tablets after tonsillectomy can reduce the amount and severity of bleeding compared to the hospital protocol. Daflon, whose main ingredient is 500 mg Diosmin, is a flavonoid and helps strengthen vascular walls and reduce inflammation (52). Also, a case-control study by Thejas et al. (2021) on 133 patients aged 6 to 30 years showed that the use of 3% hydrogen peroxide is very effective in preventing blood loss after tonsillectomy (58). The results of a trial study by Ghadami et al. (2022) on 109 patients aged 5 to 18 years showed that the administration of 40 mg of 1% lidocaine and 5 micrograms of epinephrine reduced the amount of bleeding (69). Therefore, it is recommended that specialists design and conduct trial studies to investigate the effectiveness of hydrogen peroxide, Daflon tablets, and adrenaline injection combined with tramadol on reducing bleeding after tonsillectomy.

The results of the review of studies showed that the administration of ibuprofen did not result in a statistical difference in bleeding after tonsillectomy compared to patients who did not receive ibuprofen. The results of a retrospective study by Miller et al. (2021) on 4098 children aged 2 - 18 years (46) and a retrospective study by Patel et al. (2020) on 132 children under 18 years of age (42) did not show the effectiveness of ibuprofen administration in reducing bleeding after tonsillectomy. However, a study by Rosi-Schumacher et al. (2024) on 199 people with a dose of 400 mg of intravenous ibuprofen reduced the amount of bleeding after tonsillectomy (64). Ibuprofen, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), may cause temporary increased bleeding in some people by inhibiting thrombocythemia. The difference in the effectiveness of ibuprofen in reducing post-tonsillectomy bleeding may depend on individual clinical characteristics, which requires further investigation. It is suggested that the ibuprofen dosage be adjusted more precisely for the age and weight of the subjects.

The results showed that local anesthetic injection of epinephrine combined with lidocaine anesthetic injection reduced bleeding compared to epinephrine anesthetic injection alone. The results of a pilot study by Li (2021) on 68 children showed that simultaneous injection of local anesthetic epinephrine with lidocaine anesthetic injection reduced bleeding after tonsillectomy (45). Epinephrine and lidocaine are two common local anesthetics that have analgesic and hemostatic properties. Recently, local injection of epinephrine and lidocaine in tonsillectomy has received increasing attention. However, few studies have been conducted in this area. Therefore, more studies are needed in this area.

The results of this study showed that the administration of ketorolac was not effective in reducing the amount of bleeding after tonsillectomy. The results of a retrospective study by Kolb et al. (2021) on 1920 children under 19 years of age (54), a retrospective study by Shaikh et al. (2024) on 307716 children under 18 years of age (55), a retrospective study by Feldman et al. (2024) on 4694 children under 18 years of age (59), a study by McClain et al. (2020) on 263 patients over 18 years of age (62), and the results of a retrospective study by Rabbani et al. (2020) on 1322 children under 18 years of age (60) showed that the administration of ketorolac did not reduce the rate of bleeding after tonsillectomy in their statistical population.

5.1. Conclusions

The prevalence of primary, secondary, and total bleeding in individuals after tonsillectomy was variable. In most studies, more than half of patients experienced bleeding after tonsillectomy. Of course, the high prevalence in these studies may be due to pre- and post-tonsillectomy care. Since the most important factor in bleeding after tonsillectomy is the lack of compliance with pre- and post-tonsillectomy care, it is recommended that necessary measures be taken to inform the general population. Columnar suture technique, surgical techniques, patient clinical characteristics, local anesthetic injection of epinephrine combined with lidocaine, hydrogen peroxide, Daflon tablet, and adrenaline injection combined with tramadol separately are effective in controlling or reducing bleeding after tonsillectomy. On the other hand, the prescription of ibuprofen has been effective in some studies but not significantly effective in others. However, ketorolac is not effective in controlling or reducing bleeding after tonsillectomy in all studies. Therefore, ENT surgeons are advised not to prescribe ibuprofen and ketorolac to control or prevent bleeding after tonsillectomy.

5.2. Limitations

The full text of some articles was not available, and the request to the corresponding authors via email was also unsuccessful, so these articles were excluded from the study.

Also, the lack of access to these and projects that did not result in an article and articles that were published in languages other than Persian and English in the database were another limitation of the study. It is recommended that future research conduct a broader search with more database coverage.