1. Background

Low birth weight (LBW) is considered a key predictor of perinatal survival, infant mortality and morbidity, and is associated with a heightened risk of diseases and developmental impairments in later life (1). According to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), LBW is defined as less than 2500 g irrespective of gestational age (2). An estimated 30 million LBW babies are born worldwide each year, accounting for 23.4% of all births, and they frequently have both immediate and long-term health adverse consequences (3). Estimates indicate that nearly 96% of infants with LBW are delivered in developing countries, of which roughly 72% are in Asia and 22% in Africa (4).

Women in developing countries, especially Asians, are more likely to give birth to LBW babies than women in developed countries. The LBW babies are also more common in rural women than in urban women due to less access to prenatal care, less awareness of nutrition, and poor diet quality (5). In general, different factors have been identified as determinant for LBW such as the family’s income, smoking during pregnancy, multiple pregnancies, parents' lifestyle (especially the mother), socio-economic factors, preterm birth, Body Mass Index (BMI), environmental and nutritional factors, and lack of prenatal care (6, 7). A history of LBW over normal birth weight (NBW) increases an adult's chance of developing certain conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, stroke, and coronary heart disease (8).

To mitigate the adverse consequences of LBW, it is essential to obtain accurate data on its prevalence, particularly in developing countries. Also, identifying the factors associated with LBW is essential because understanding these determinants can help health policymakers and practitioners design effective prevention and intervention programs (9).

2. Objectives

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of LBW and to examine the association between its contributing factors and birth weight in Khash city, Iran.

3. Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on mothers who gave birth and attending health care centers in Khash city, Sistan and Baluchestan province, Iran from January 01 to December 30, 2023. There are three active comprehensive health service centers, and sampling was conducted in all of them. In total, 590 mothers delivered and their neonate included in this study using census method. Stillbirth, infants with birth defects and whose information was incomplete were excluded from the study. A self-administered questionnaire was employed to collect data on the sociodemographic characteristics of mothers and newborn-related characteristics; it was developed for this study, reviewed by experts for content validity, and pilot-tested for clarity and reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.78).

The SPSS software package, version 22, was used to analyze data. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD). To identify association between LBW and the independent variables, chi-square test was applied. Then, covariates which had a P-value < 0.2 were entered into the multivariable logistic regression analysis to calculate the adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

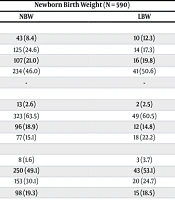

The average age of mothers during childbirth was 28.8 ± 6.9, and 46% were over 30 years old. 63% of mothers had secondary education. More than 90% of mothers were housewives and nearly 70% lived in cities. Most mothers did not smoke during pregnancy (93%). Also, 4% of the mothers had multiple pregnancies. Twenty-six percent had a history of abortion. More than half of the mothers (63%) had visited the health center more than 5 times for prenatal care. Also, half of them (56%) had normal BMA during pregnancy (Table 1).

| Variables | Values | Newborn Birth Weight (N = 590) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NBW | LBW | |||

| Mother’s age at birth of child (y) | 0.3 | |||

| 15 - 19 | 53 (9.0) | 43 (8.4) | 10 (12.3) | |

| 20 - 24 | 139 (23.6) | 125 (24.6) | 14 (17.3) | |

| 25 - 29 | 123 (20.8) | 107 (21.0) | 16 (19.8) | |

| > 30 | 275 (46.6) | 234 (46.0) | 41 (50.6) | |

| Mean ± SD | 28.8 ± 6.9 | - | - | |

| Mother’s education | 0.4 | |||

| Illiterate | 15 (2.5) | 13 (2.6) | 2 (2.5) | |

| Secondary school | 372 (63.1) | 323 (63.5) | 49 (60.5) | |

| High school | 108 (18.3) | 96 (18.9) | 12 (14.8) | |

| College | 95 (16.1) | 77 (15.1) | 18 (22.2) | |

| Father’s education | 0.4 | |||

| Illiterate | 11 (1.9) | 8 (1.6) | 3 (3.7) | |

| Secondary school | 293 (49.7) | 250 (49.1) | 43 (53.1) | |

| High school | 173 (29.3) | 153 (30.1) | 20 (24.7) | |

| College | 113 (19.2) | 98 (19.3) | 15 (18.5) | |

| Mother’s occupational status | 0.002 | |||

| Housewife | 550 (93.2) | 481 (94.5) | 69 (85.2) | |

| Employed | 40 (6.8) | 28 (5.5) | 12 (14.8) | |

| Residence | 0.7 | |||

| Urban | 418 (70.8) | 362 (71.1) | 56 (69.1) | |

| Rural | 172 (29) | 147 (28.9) | 25 (30.9) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.4 | |||

| Baluch | 496 (84.1) | 427 (83.9) | 69 (85.2) | |

| Sistani | 22 (3.7) | 21 (4.1) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Other | 72 (12.2) | 61 (12.0) | 11 (13.6) | |

| Consanguinity | 0.3 | |||

| Yes | 196 (33.2) | 173 (34.0) | 23 (28.4) | |

| No | 394 (66.8) | 336 (66.0) | 58 (71.6) | |

| Smoking during pregnancy | 0.5 | |||

| Yes | 36 (6.1) | 30 (5.9) | 6 (7.4) | |

| No | 554 (93.9) | 497 (94.1) | 75 (92.6) | |

| Type of pregnancy | 0.001 | |||

| Single | 563 (95.4) | 504 (99.0) | 59 (72.8) | |

| Multiple | 27 (4.6) | 5 (1.0) | 22 (27.2) | |

| Complication during pregnancy | 0.2 | |||

| Yes | 251 (42.5) | 212 (41.7) | 39 (48.1) | |

| No | 339 (57.5) | 297 (58.3) | 42 (51.9) | |

| Number of ANC visit | 0.07 | |||

| Less than 5 time | 210 (35.6) | 174 (34.2) | 36 (44.4) | |

| More than 5 time | 380 (64.4) | 335 (65.8) | 45 (55.6) | |

| Counseling on nutrition at ANC | 0.8 | |||

| Yes | 132 (22.4) | 112 (22.0) | 20 (24.7) | |

| No | 458 (77.5) | 396 (77.8) | 61 (75.3) | |

| Gestational (wk) | 0.001 | |||

| ≤ 37 | 120 (20.3) | 75 (14.7) | 45 (55.6) | |

| > 37 | 470 (79.7) | 434 (85.3) | 36 (44.4) | |

| BMI during pregnancy | 0.4 | |||

| Thin | 67 (11.4) | 61 (12.0) | 6 (7.4) | |

| Normal | 334 (56.6) | 284 (55.8) | 50 (61.7) | |

| Overweight | 138 (23.4) | 118 (23.2) | 20 (24.7) | |

| Fat | 51 (8.6) | 46 (9.0) | 5 (6.2) | |

| Abortion | 0.3 | |||

| Yes | 157 (26.6) | 132 (25.9) | 25 (30.9) | |

| No | 433 (73.4) | 377 (74.1) | 56 (69.1) | |

| Sex of the neonate | 0.07 | |||

| Male | 309 (52.4) | 274 (53.8) | 35 (43.2) | |

| Female | 281 (47.6) | 235 (46.2) | 46 (56.8) | |

| Height of neonate | 0.001 | |||

| < 50 | 500 (84.7) | 420 (82.5) | 80 (98.8) | |

| > 50 | 90 (15.3) | 89 (17.5) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Mean ± SD | 48.8 ± 2.3 | - | - | |

| Weight of neonate (g) | - | |||

| ≤ 2500 | 81 (13.7) | - | - | |

| > 2500 | 509 (86.3) | - | - | |

| Mean ± SD | 2992.9 ± 482.7 | - | - | |

Abbreviations: NBW, normal body weight; LBW, low birth weight; SD, standard deviations; BMI, Body Mass Index.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or unless otherwise indicated.

A total of 590 live birth occurred during the 1-year study period, in which 81 were LBW. Therefore, the prevalence of LBW was estimated as 13.7% (95% CI: 11 - 16.7). Moreover, the birth weight of 5 live cases (0.8%) was very LBW (birth weight < 1500 g). Fifty-two of the infants were boys. The average weight of babies was 2992.9 (482.7). Also, their average height was 48.8 (2.3) and 84% were less than 50 cm tall.

There was a statistically significant association between LBW and mother’s occupational status, gestational age, type of pregnancy and height of neonate (P < 0.05). In addition, according to the results of the multiple logistic regression, gestational age less than 37 weeks and baby's height of less than 50 cm increase the risk of LBW by 4.4 times (95% CI = 2.5 - 7.9) and 41.2 times (95% CI = 3.6 - 469.4), respectively (Table 2).

| Variables | OR (95%CI) | SE | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational (Less < 37 wk) | 4.4 (2.5 - 7.9) | 0.29 | 0.001 |

| Height of neonate (< 50 cm) | 41.2 (3.6 - 469.4) | 1.24 | 0.003 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

5. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the prevalence of LBW and to identify its associated factors in Khash city, Iran. The results showed that the overall prevalence of LBW is 13.7% (95% CI: 11 - 16.7), which corresponds to the LBW rate in the top 20 countries with the highest infant mortality rates [13% (95% CI: 11% to 14%)] (10).

Furthermore, the findings of this study were lower than the global and sub-Saharan African estimates of 14.6% and 16.4%, respectively, as reported in national, regional, and global systematic analyses (11).

According to previous studies the proportion of newborn with LBW was 9% in Iran, (12), 9.4% in Nepal (13) and 9.3% in the United States (1), 17.29% in India (14).

In addition, the results of a study in 35 countries in South Africa showed that the overall prevalence of LBW was 9.47% (3). This could be attributed to differences in study population and design, or to socio-demographic, economic, and health care system differences. The mean ± SD birth weight of the children in our analysis was 2992.9 ± 482.7, which is lower than the newborns on the United States of America (3.45 kg) on whom WHO’s reference standard is based (15).

The results of this study showed that babies of mothers who were housewife and have low economic status were more likely to have LBW. This result aligns with previous studies indicating that poor economic status is associated with an increased risk of delivering a LBW infant (16, 17). Also the study conducted in India displayed that an increase in the education level of Women or Wealth Index lead to significantly decreased odds of LBW in the newborn (14). This may be attributed to the fact that women with better economic and occupational status tend to have improved nutritional status during pregnancy (18, 19). Additionally, greater wealth and employment stability are likely to enhance women’s health-seeking behaviors, which contribute to reducing the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

In this study, prevalence of LBW among premature neonates was higher than babies born at 37 weeks of pregnancy or later. The findings of this study were consistent with those of studies conducted in Zimbabwe, and Ethiopia (20, 21). It could be because the maximum weight gain is for babies who are born in the third trimester of pregnancy and premature babies who are immature and have a low level of physical development (6).

Results of this study like other study showed that the multiple pregnancy is associated with LBW (14). This could be because twin pregnancies are associated with increased demand for nutrients and oxygenated blood (22). Moreover, a systematic review study examined the risk factors associated with twin pregnancies, highlighting that multiple gestation is recognized as one of the significant factors contributing to LBW in newborns (23). Also, baby girls are more likely to have LBW than baby boys, which is consistent with other studies (4, 14), which suggestive of the phenomenon of a small, although possibly gendered inequality contributing to differential growth.

This study had several limitations. It relied on secondary data from the SIB health information system, and some incomplete records were excluded, which may have reduced the sample size and generalizability. Additionally, the cross-sectional design prevented causal inference, and possible data-entry errors could have introduced information bias. Future studies are recommended to adopt longitudinal or prospective designs to better identify causal associations. Conducting similar studies in different regions with larger sample sizes could improve the external validity and generalizability of the results.

5.1. Conclusions

This study showed that the prevalence of LBW is virtually high in Khash city. Also, LBW is associated with a variety of factors, including maternal occupation, gestational age, and multiple births, neonate’s height. As a result, appropriate intervention programs, including education of proper nutrition during pregnancy to housewives along with the implementation of proven methods to prevent preterm birth, can help reduce cases of LBW and thus increase survival in children. Also, pregnant women should also be evaluated for these associated risk factors during their regular follow-up visits.