1. Background

Non-specific chronic low back pain (NSCLBP) is a prevalent musculoskeletal disorder affecting millions worldwide, leading to significant impairments in daily functioning, work productivity, and overall quality of life (1). Numerous studies have verified that 70 - 84% of people experience low back pain at some point in their lives, and a considerable portion go on to develop chronic forms, highlighting its importance as a serious public health issue (2, 3). One of the primary biomechanical contributors to NSCLBP is lumbar hyperlordosis, which alters spinal alignment, increases mechanical stress on intervertebral structures, and contributes to anterior pelvic tilt (APT) (4). These structural deviations exacerbate pain and contribute to postural instability and movement dysfunctions (5).

Current therapeutic strategies for NSCLBP encompass pharmacological management, physiotherapeutic modalities, and corrective exercise regimens. While these interventions may offer temporary symptomatic relief, their long-term efficacy in addressing underlying biomechanical dysfunction remains equivocal (6). Various interventions such as core stabilization exercises, manual therapy, and motor control training have demonstrated positive outcomes in the management of NSCLBP (7). Specifically, core stability exercises have been associated with reduced pain intensity, improved functional outcomes, and enhanced spinal stability through targeted activation of deep trunk musculature (8). For example, McGill highlighted that appropriate activation of the deep trunk musculature contributes to spinal stability and reduces spinal load, which is crucial in the management of low back pain (5). Lumbar stabilization exercises, particularly those engaging the multifidus and transverse abdominis, have also shown efficacy in improving spinal alignment and reducing pain among individuals with chronic LBP (4).

Among emerging rehabilitation paradigms, dynamic neuromuscular stabilization (DNS) has garnered attention as an innovative motor control intervention. Grounded in neurodevelopmental principles, DNS facilitates the activation of deep-stabilizing muscles and the re-establishment of optimal motor patterns (5). In contrast to traditional interventions such as Pilates and core stabilization — which rely predominantly on voluntary muscle engagement — DNS prioritizes involuntary, automatic postural regulation via central nervous system reprogramming (6). Preliminary findings suggest that DNS may improve proprioception, muscular endurance, and postural control; however, direct comparative analyses with conventional modalities, such as Pilates, are scarce (9).

The DNS, developed by Pavel Kolar and based on developmental kinesiology, integrates diaphragmatic breathing, intra-abdominal pressure modulation, and core engagement to optimize spinal biomechanics and neuromuscular coordination (5, 10). Despite its theoretical appeal and clinical promise in postural correction and pain modulation, empirical evidence evaluating DNS’s specific effects on structural abnormalities such as lumbar hyperlordosis and APT is limited (1). Existing studies have predominantly focused on general LBP management, thereby neglecting targeted biomechanical outcomes (4).

To address this gap, the present study investigates whether DNS provides superior therapeutic benefits over no intervention in correcting spinal and pelvic alignment and alleviating pain in women with NSCLBP and hyperlordosis. Can a six-week DNS intervention significantly improve lumbar curvature, APT, and pain intensity in women with NSCLBP and hyperlordosis compared to a non-treatment control?

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to assess the effects of DNS exercises on lumbar lordosis, APT, and pain in women with NSCLBP and hyperlordosis. The objective was to provide evidence regarding the potential of DNS to address both symptomatic and structural issues.

3. Methods

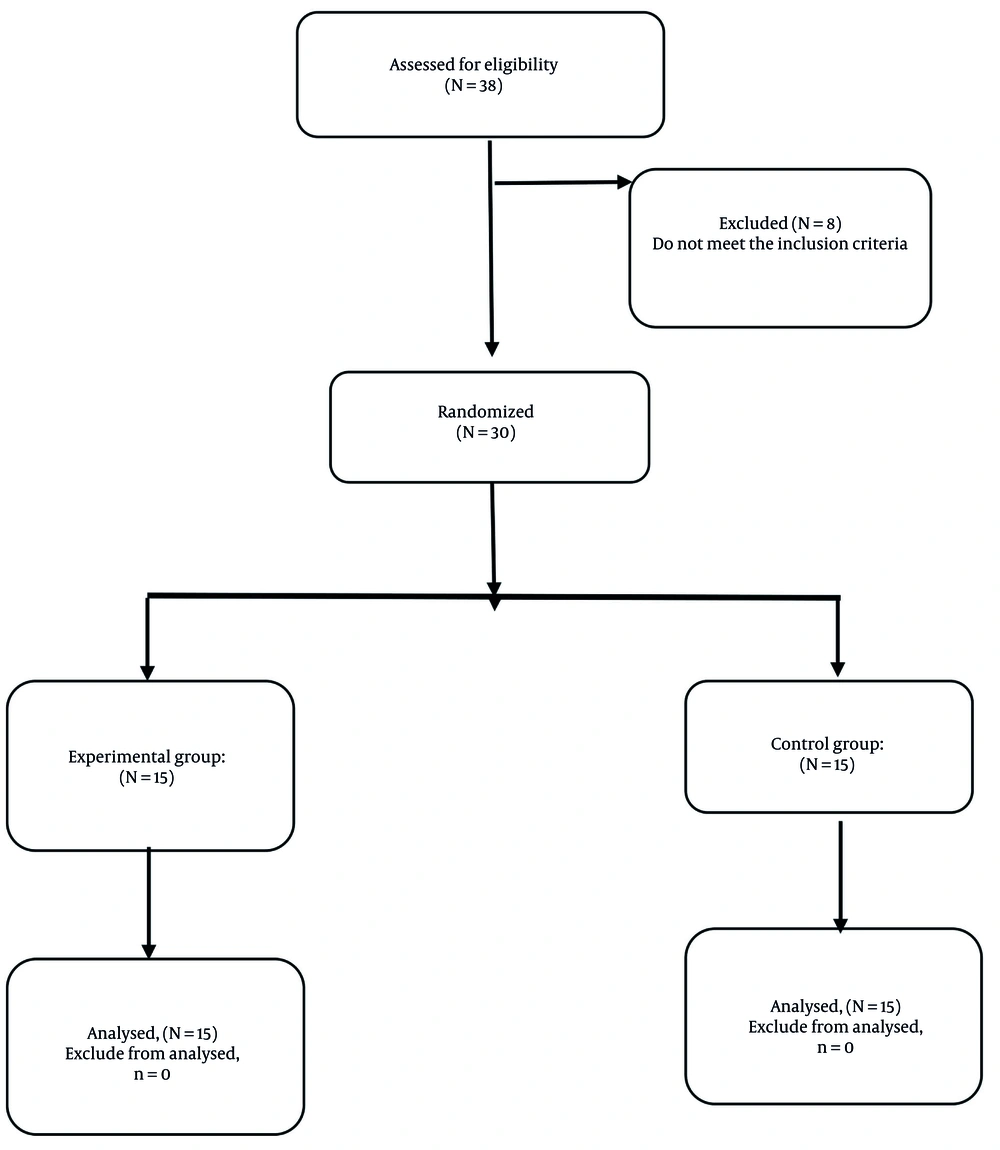

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Sport Sciences Research Institute (IR.SSRC.REC.1402.254). A quasi-experimental design was employed to evaluate the effects of the intervention, utilizing non-random convenience sampling to recruit women aged 30 to 50 years residing in Bojnord, Iran. The required sample size was calculated a priori using G*Power 3.1 software, based on an assumed effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.8), α = 0.05, and power (1 - β) = 0.80. This effect size was derived from previous studies on DNS and core stabilization interventions in individuals with chronic low back pain (1). To account for potential attrition, a total of 30 participants were enrolled in the study. After meeting the inclusion criteria, 30 participants were assigned to either the experimental group (n = 15) or the control group (n = 15). The assignment was performed using a computer-generated random number table, with each participant receiving a unique identification number. Random allocation occurred without stratification, ensuring that all participants had an equal chance of being assigned to either group. This method was considered suitable since baseline variables — pain intensity, lumbar lordosis angle, and APT — were similar across participants. Figure 1 (CONSORT flow diagram) shows the participant flow throughout the study phases.

To minimize measurement bias, all outcome assessments were conducted by a blinded evaluator who was unaware of group assignments. Due to the nature of the intervention, participant blinding was not feasible. However, participants were not informed of the specific outcomes being assessed (i.e., lumbar lordosis, APT, and pain intensity); instead, only general information regarding posture and back health was provided. While this approach helped reduce expectancy bias, it is acknowledged that the use of a self-reported measure, such as the Visual Analog Scale (VAS), may have introduced some degree of subjective response bias.

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria were having a history of NSCLBP lasting at least three months (11), an age range of 30 to 50 years, and no neurological impairments such as limb numbness or weakness. Additionally, participants were required to have no vestibular disorders or severe psychological conditions (12) and an Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire (OLBPDQ) score of less than 15 (13). Structural eligibility criteria included lumbar lordosis greater than 51 degrees (14), kyphosis less than 42 degrees (14), and an APT exceeding 5 degrees (15).

Exclusion criteria included participants who failed at least 80% of training sessions, withdrew due to personal reasons or health issues, or did not adhere to the prescribed exercise protocol. Additionally, those who experienced worsening symptoms requiring medical intervention were also excluded. A multidisciplinary team consisting of a physiotherapist, an orthopedic specialist, and a corrective exercise specialist evaluated inclusion and exclusion criteria, ensuring a rigorous selection process.

3.2. Study Setting and Ethical Considerations

The study occurred at the corrective movement center of Bojnord, where participants received all interventions and assessments. The exercises were prescribed by a specialist in corrective exercises, who evaluated each participant based on standardized movement assessments and clinical criteria. The prescribed exercises were designed for individuals with NSCLBP to improve spinal stability and postural alignment. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant, with a detailed information form explaining study goals, methodology, risks, and rights. Participants completed a health screening to ensure they met inclusion criteria, including an assessment to rule out severe underlying conditions.

3.3. Measurement Tools

Visual Analog Scale for Pain: The VAS is a simple and widely used tool for measuring pain intensity. It consists of a straight line, usually 10 centimeters long, with one end representing "no pain" (0) and the other end representing "worst possible pain" (10). Individuals mark a point on the line corresponding to the intensity of their pain, and the distance from the start to the marked point is recorded as the pain score. The VAS is highly sensitive and is particularly useful for assessing small changes in pain intensity after therapeutic interventions (16), such as DNS exercises in individuals with hyperlordosis and non-specific chronic back pain.

Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire: The OLBPDQ is a widely recognized tool used to assess the impact of low back pain on an individual’s daily life and functionality. It consists of 10 sections, each addressing a specific aspect of daily activities such as sitting, standing, walking, lifting, and sleeping. Each section is scored from 0 to 5, where 0 represents minimal disability, and 5 indicates maximum disability. The total score is then converted into a percentage to categorize the level of disability: Minimal (0 - 20%), moderate (21 - 40%), severe (41 - 60%), very severe (61 - 80%), and complete disability or bed-bound (81 - 100%). In studies, such as those on individuals with hyperlordosis and non-specific chronic back pain, this questionnaire is often used to measure the effectiveness of interventions by comparing pre- and post-treatment scores. Its reliability and validity have been previously established, with a coefficient of 0.84 (17).

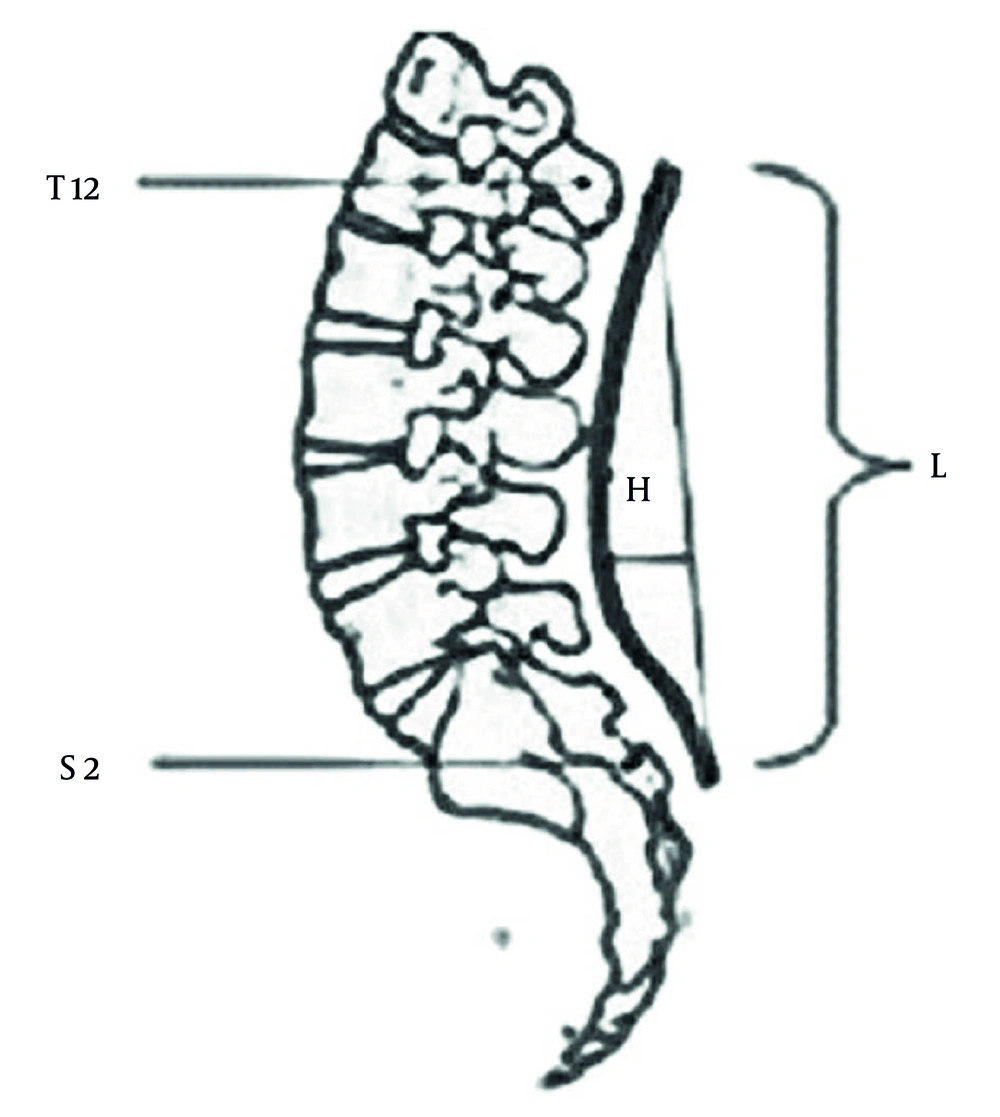

Lumbar lordosis angle measurement: This study measured lumbar lordosis using T12 and S2 as reference points and a flexible ruler. After marking these vertebrae and identifying the deepest point of the curve, the ruler was aligned and the spine’s contour transferred. The lordosis angle was then calculated using a standard formula (18, 19). This non-invasive approach enhances accuracy, improves comparability with radiographic techniques, and reduces measurement errors, making it practical for both clinical and research use (Figure 2). The Iranian flexible ruler has demonstrated high reliability (ICC > 0.85) and strong validity (r = 0.86) when compared to radiographic measurements, as reported in previous studies (20). Although this study did not conduct radiographic validation due to ethical and logistical reasons, earlier research confirms the method’s reliability. These results apply specifically to Iranian populations. We acknowledge that differences in lumbar curvature across populations may impact the generalizability of our findings. Individuals were selected who had a lumbar lordosis angle that exceeded the average norm for Iranian women (14). The lordosis angle was calculated using the formula: θ = 4 × arctangent (2h/L) Where h is the vertical distance from the deepest point of the curve to the baseline L, representing the straight-line distance between T12 and S2. The formula for calculating the lordosis angle was derived from established geometric principles using T12 and S2 landmarks and has been validated in prior studies with Iranian populations (20).

Measurement of lumber lordosis by flexible ruler between T12 and S2 where H is the deepest part of the curve and L is the length of the curve (20).

Anterior pelvic tilt measurement: To assess APT, participants stood in a relaxed, upright position with their feet shoulder-width apart. The examiner identified and marked the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) and posterior superior iliac spine (PSIS) as anatomical reference points. The angle formed between these landmarks relative to the horizontal plane was then measured using a digital inclinometer. An angle greater than 5 degrees was considered indicative of APT. Additionally, the vertical height difference between ASIS and PSIS was noted to enhance measurement accuracy (15). A corrective movement specialist conducted all measurements. Previous studies have reported good inter-rater reliability for pelvic tilt measurements (ICC = 0.81 - 0.88) and good test-retest reliability within sessions (ICC = 0.88 - 0.95) (21).

3.4. Interventions

The experimental group followed a DNS exercise protocol designed to improve neuromuscular stability. This program consisted of three supervised sessions per week over a period of six weeks. Each session included a 10-minute warm-up, 45 minutes of DNS exercises with breathing correction, and a 5-minute cooldown. The exercises were progressive, increasing in complexity week by week, starting with basic postural and diaphragmatic breathing movements. Positions included 90-90 lying supine, prone lying, side-lying, tripod kneeling, squatting, and standing (22). To ensure structured progression, specific sets and repetitions were prescribed weekly, and exercise difficulty advanced based on posture complexity, motor control demands, and limb movement integration. A detailed table outlining this progression has been added to the manuscript (Table 1). For example, week 1 focused on diaphragmatic breathing and basic core activation, while later weeks included dynamic stabilization and functional movement patterns. A corrective movement specialist with a master’s degree in corrective exercise and sports injuries oversaw all sessions to ensure proper form and technique.

| Weeks | Exercise Focus | Position/Posture | Sets×Reps | Progression Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Core activation, breathing control | 90-90 supine with diaphragmatic breathing | 2 × 10 breaths | Emphasis on proper breathing and intra-abdominal pressure |

| 2 | Core stability, pelvic alignment | 90-90 supine with limb movement | 3 × 10 | Add dynamic limb movements while maintaining core control |

| 3 | Neuromuscular control | Quadruped position (hands and knees) | 3 × 12 | Increase balance challenge with limb lift |

| 4 | Trunk stability, scapular control | Tripod sitting, supported kneeling | 3 × 12 - 15 | Increase holding time and reduce external support |

| 5 | Load tolerance, postural endurance | Bear crawl and modified standing | 3 × 15 | Add isometric holds, transitions between postures |

| 6 | Functional integration | Standing DNS positions, wall-supported | 3 × 15 - 20 | Increase task complexity (e.g., arm elevation, single-leg) |

Abbreviation: DNS, dynamic neuromuscular stabilization.

The control group continued their regular daily physical activities but did not engage in any DNS or structured stability training. To avoid potential confounding, clear exclusion criteria were established. Control participants were instructed to refrain from any therapeutic or structured exercise, including yoga, Pilates, physiotherapy routines, or core-strengthening exercises. Permitted activities were limited to light, non-specific daily tasks such as walking, casual stretching, and household chores. Regular monitoring was implemented, and participants maintained a structured activity log throughout the study. These logs were reviewed weekly to ensure compliance, and no control participant reported engaging in restricted activities during the intervention period.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

The normality of data was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and variance equality was assessed using Levene’s test. Homogeneity of regression slopes was tested using ANCOVA, which showed no violations (P > 0.05). A paired t-test was used for intra-group comparisons, and an independent t-test was used for inter-group comparisons. Pretest scores were included as a covariate in the ANCOVA model. Statistical significance was set at α ≤ 0.05. Data were analyzed using SPSS 22.

4. Results

Table 2 provides detailed descriptive information on the participants’ age, height, and weight, offering an overview of their characteristics (Table 2).

| Variables and Groups | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.172 | |

| Experimental (n = 15) | 40.26 ± 6.75 | |

| Control (n = 15) | 37.33 ± 4.46 | |

| Height | 0.229 | |

| Experimental (n = 15) | 159.06 ± 6.45 | |

| Control (n = 15) | 161.73 ± 5.36 | |

| Weight | 0.678 | |

| Experimental (n = 15) | 56.73 ± 7.21 | |

| Control (n = 15) | 57.66 ± 4.59 |

The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed the data’s normality for both the pre-test and post-test stages across all variables (P > 0.05). Additionally, Levene’s test confirmed the equality of variances, and the homogeneity of regression slopes was validated at a 0.05 significance level, indicating that the data met the assumptions for further analysis. The dependent t-test showed significant reductions in lordosis angle, APT, and pain levels for the experimental group, indicating the effectiveness of DNS exercises. The control group showed no significant changes (P > 0.05). Table 3 summarizes the pre- and post-test values for both groups, highlighting the impact of the intervention.

| Groups | SD ± Mean | df | t | P-Value | Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-test | Post-test | |||||

| Lordosis angle | ||||||

| Experimental | 59.00 ± 2.72 | 55.33 ± 2.82 | 14 | 3.92 | 0.002 | 1.33 |

| Control | 57.86 ± 3.06 | 58.73 ± 2.98 | 14 | -0.79 | 0.442 | -0.29 |

| Anterior hip rotation angle | ||||||

| Experimental | 13.54 ± 1.97 | 10.50 ± 2.75 | 14 | 3.58 | 0.003 | 1.27 |

| Control | 12.88 ± 2.33 | 13.12 ± 2.33 | 14 | -0.26 | 0.766 | -0.10 |

| Pain variable | ||||||

| Experimental | 6.93 ± 2.21 | 4.20 ± 2.93 | 14 | 2.38 | 0.032 | 1.05 |

| Control | 6.60 ± 2.06 | 6.26 ± 2.15 | 14 | 0.36 | 0.718 | 0.16 |

The ANCOVA analysis revealed that DNS exercises had a significant effect on reducing lordosis angle, correcting APT, and reducing pain levels. These results indicate that DNS exercises effectively improve biomechanical conditions and reduce pain in individuals with hyperlordosis (Table 4).

| Variables | SS | DF | MS | F | P-Value | η2 (Eta squared) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lordosis angle | 87.70 | 1 | 70.87 | 10.08 | 0.004 | 0.272 |

| APT | 48.55 | 1 | 48.55 | 7.19 | 0.012 | 0.210 |

| Pain | 26.75 | 1 | 26.75 | 4.77 | 0.038 | 0.150 |

Abbreviations: SS, sum of squares; DF, degrees of freedom; MS, mean square; η2, Eta squared (effect size); APT, anterior pelvic tilt.

5. Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to assess the impact of DNS exercises on lumbar lordosis, APT, and pain levels in individuals with hyperlordosis and non-specific chronic back pain. The results of this investigation indicate that DNS exercises significantly reduced lordosis angle, APT, and pain levels in the experimental group. Specifically, the experimental group demonstrated considerable improvements, including a reduction in lordosis angle (t = 3.92, P = 0.002), APT (t = 3.58, P = 0.003), and pain levels (t = 2.38, P = 0.032). ANCOVA analysis further supported these findings, which revealed significant differences in the lordosis angle, APT, and pain reduction compared to the control group. This suggests that DNS exercises may provide a promising intervention for addressing lumbar and pelvic misalignments associated with chronic back pain.

The findings of this study align well with several other studies that explored the effects of DNS exercises on postural control, spinal alignment, and pain relief. For instance, Lim et al. found that DNS exercises effectively improved posture and spinal alignment in individuals with chronic back pain by reducing abnormalities in curvature and enhancing musculoskeletal balance (23). Similarly, Mohammad Rahimi et al. observed that DNS exercises focusing on neuromuscular coordination and respiratory function significantly improved physical alignment and reduced maladjustments, supporting the current study’s results regarding improved postural stability (24). Additionally, Bae et al. highlighted that DNS exercises resulted in significant reductions in spinal abnormalities, including lordosis, reinforcing the broader potential of DNS in managing postural deviations (25).

The consistency in findings across these studies can be attributed to the common mechanism through which DNS exercise functions — by targeting deep stabilizer muscles such as the transverse abdominis, multifidus, and diaphragm. These muscles play a crucial role in spinal stability and alignment, and their activation through DNS exercises enhances core stability, corrects muscular imbalances, and improves postural control. Moreover, DNS improves proprioceptive input by engaging joint receptors and mechanoreceptors, which may contribute to reducing APT through neuromuscular reeducation. This can involve the inhibition of overactive hip flexors such as the iliopsoas and the facilitation of underactive muscles like the gluteus maximus, thereby restoring pelvic neutrality and lumbopelvic rhythm (5, 22).

In contrast, Ghiasi et al. did not observe significant changes in lordosis angle following stabilization exercises, including DNS (4). This discrepancy may stem from differences in intervention intensity, duration, and progression methodology. Because our study’s DNS protocol integrated progressive complexity and supervised application, it may have activated the deep stabilizing muscles more effectively. Furthermore, the precise performance of DNS techniques is pivotal for eliciting biological adaptation; this factor may not have been adequately considered in previous studies that used less structured or shorter interventions.

Furthermore, Mousavi and Mirsafaei Rizifound that while both DNS and core stability exercises significantly reduced pain, DNS exercises primarily improved quality of life, while core stability exercises had a greater impact on hamstring flexibility. In contrast, the present study found that DNS exercises had a simultaneous and significant effect on multiple variables, including lordosis angle, pelvic tilt, and pain levels (6). This divergence could be due to differences in the exercise protocols used or the specific characteristics of the study populations, such as age, gender, and the severity of symptoms.

In terms of clinical relevance, the reductions observed in this study are not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful. Specifically, Cohen’s d values for lordosis (1.33) and pain (1.05) represent large effect sizes, suggesting strong intervention effects. The average reduction of ~ 4° in lumbar lordosis in the experimental group aligns with previous thresholds for functional improvement, which are associated with decreases in Disability Index scores and improvements in daily functioning (13, 14). These changes could contribute to enhanced dynamic stability, reduced spinal loading, and improved participation in physical activities.

The results of this study show that DNS exercises have significant clinical effects in reducing lumbar lordosis angle, APT, and pain intensity in individuals with hyperlordosis and non-specific chronic back pain. The observed reductions in lordosis angle and pain intensity are directly linked to improved functional outcomes and decreased discomfort, which can enhance patient well-being and quality of life. These changes highlight the clinical relevance of DNS exercises in rehabilitation practices, as they help correct postural deviations and alleviate pain. The findings suggest that DNS exercises could be an effective intervention for physical therapists and clinicians to improve spinal alignment and reduce pain in patients with chronic back pain.

Although this study provides valuable insights, it is important to acknowledge several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to larger populations. A larger sample size would improve the statistical power and robustness of the results. Additionally, the study focused exclusively on female participants aged 30 - 50 years from a specific geographic location (Bojnord), which reduces the applicability of the results to other populations, such as males, individuals outside the specified age range, or those from different cultural or geographic backgrounds. The lack of blinding in the study is another significant limitation, as this may have introduced bias in assessing outcomes. Moreover, while control group participants were instructed to maintain daily routines and refrain from structured exercise, their activity logs were not quantitatively analyzed. A qualitative review of logs showed no engagement in restricted exercises. Future studies should incorporate minimal clinically important differences (MCID) to assess the clinical significance of the findings. Additionally, RCTs with a six-month follow-up are recommended to evaluate the long-term effects of DNS exercises. Expanding research to include more diverse populations would also enhance the generalizability of the results.

5.1. Conclusions

This study suggests that DNS exercises may help reduce lumbar lordosis, decrease APT, and alleviate back pain in women with hyperlordosis. However, given the quasi-experimental design, small sample size, single-gender sample, and single-center approach, results should be interpreted with caution. While the findings are promising, further research with larger, more diverse populations and more rigorous designs is needed to confirm these effects. The DNS exercises may be incorporated into rehabilitation programs to improve posture and alleviate pain, but the preliminary nature of these findings should be acknowledged. Future studies should consider these limitations and explore these effects in broader, more diverse populations.