1. Background

Representing a major concern for sport organizations and clubs worldwide, talent development is manifested in their systemic and financial structures (1). Talent is often assumed to be an innate disposition in many sport programs. Accordingly, the focus of these programs is built on a person's anthropometric, athletic, and technical characteristics at a given instant to reveal the possibility of attaining elite status. Such one-shot selection criteria have been shown to be flawed, however. For example, only a weak correlation has been found between athletic success at lower ages and athletic success at elite ages (1, 2), findings which have underlined the nonlinearity of athletic talent development (3). Talent is thus not only innate but also built and developed as time passes. For athletic potential to be converted into high achievement, various performance factors from personal dispositions to environmental characteristics interact with each other. Therefore, to fulfill their potential, research suggests that individuals should possess and develop appropriate psychobehavioral skillsets. One such prominent approach is called Psychological Characteristics of Developing Excellence (PCDEs) (2, 4, 5).

1.1. The Importance of the Psychological Characteristics of Developing Excellence

The PCDEs allow for an effective interaction with the developmental opportunities provided to individuals (4). On the path to excellence, one is required to acquire these skills and improve them whenever developmental opportunities arise (6). In MacNamara et al.’s view, these psychological skills are critical determinants of development (e.g., coping skills, commitment, imagery) that help eager elites optimize developmental opportunities, adapt to setbacks, and negotiate key transitions faced on the development pathway in an effective way (7). The identification and development of PCDEs in sport have gained increasing importance in recent years. Although the development of excellence and associated psychological characteristics has been widely emphasized, comparatively fewer resources have been devoted to the evaluation and optimization of the excellence development process and PCDEs themselves. To optimize athletes’ development, a reliable instrument is required to assess and monitor psychological skills while providing athletes with systematic feedback. The 59-item PCDEQ, developed and validated by MacNamara and Collins (8), was designed to address this need, employing a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from very unlike me to very like me. Subsequent work indicated some psychometric and practical concerns over PCDEQ, e.g., the PCDEQ does not assess the maladaptive and dual effect PCDEs manifested in the current literature. To overcome this drawback, Hill et al. made attempts to refine the PCDEQ. The 88-item seven-factor Psychological Characteristics of Developing Excellence Questionnaire, version 2 (PCDEQ2) was consequently developed through exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (1).

The PCDEQ2 is used to monitor and assess the elite athlete on the path to excellent development. The four subscales 6, 5, 3, and 2 are psychological characteristics of positive effects, and the elite athlete is encouraged to improve them. The two subscales 1 and 7 are psychological characteristics of negative effects, and the athlete is required to learn and develop skills to cope with them. Finally, the subscale 4 is of dual effect. The PCDEQ2 is scored on a 6-point Likert-type scale (from very unlike me to very like me). Concepts and subscales include: (1) Adverse response to failure that draws mainly upon the literature on fear of failure (9, 10), and contains items associated with anxiety, depression, focus, and perfectionism. It assesses the person's maladaptive responses to failure. High scores in this area possibly reveal the athlete's developmental challenge suboptimal interaction (11); (2) imagery and active preparation that indicates the need for effective and controllable imagery to both refine skills and manage arousal (12, 13); (3) self-directed control and management that adaptively affects talent development (12, 13); (4) perfectionistic tendencies that include a set of items to assess perfectionism, anxiety, fear of failure, and the obsessive component of passion, together with one negative item that is related to realistic performance evaluation (12, 13); (5) seeking and using social support which is based on the facilitative contribution of effective support networks to the talent development pathway; (6) active coping that recognizes the proactive, self-regulated deployment of coping mechanisms. Again, the importance of holding a positive and proactive approach to challenge is a well-established factor associated with both development and performance (14); and (7) clinical indicators that incorporate mental health-related items from original constructs (6). The instrument has proven popular in applied settings, with applications ongoing in high-level academies in varied sports (including football and golf) and internationally through translations into a variety of languages, including French and Dutch.

1.2. The Need for Consideration of Wider Mediators

In addition to the need for more precise identification of psychological precursors such as PCDEs, it is essential to examine the generalizability of these constructs across cultures. While the PCDEQ has been translated and applied in other contexts, this has often been done uncritically, assuming equivalence. Transfer across European cultures may be relatively straightforward; however, genuine cross-cultural comparisons require examining more divergent cultural settings. Similarly, gender- and sport-related differences are best evaluated within the context of substantial cultural contrasts. Therefore, the validity of the PCDE approach and the application of the PCDEQ would benefit from psychometrically assessing differences across performance levels (15), genders (16), and sport types in culturally distinct populations. Our collaboration provided such an opportunity, enabling comparisons between a Western and a strongly Muslim cultural context.

1.3. The Need for Persian Version Psychological Characteristics of Developing Excellence Questionnaire, Version 2

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no prior study has translated or validated the PCDEQ2, into Persian. Therefore, the primary aim of the present study was to translate and validate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the PCDEQ2. Establishing a validated Persian version would represent a significant contribution to the global research community on talent development (1, 17), enabling broader international and cross-cultural comparisons of the PCDEQ2’s psychometric characteristics. Moreover, as sport psychologists increasingly engage in elite athletic settings — not only addressing psychopathology but also enhancing athletes’ psychological skills — the PCDEQ2 could serve as a valuable tool for Persian-speaking practitioners.

2. Objectives

This study sought to assess the reliability and validity of the Persian PCDEQ2 in evaluating the development and utilization of psychological characteristics among aspiring Persian-speaking athletes. To further confirm its validity, the questionnaire’s ability to discriminate between athletes of different performance levels, genders, and sport types (team vs. individual) was also examined, extending the psychometric evidence established by the original instrument.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This study employed a cross-sectional design to validate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the PCDEQ2. Data were collected at a single point in time, and participants completed the questionnaire to assess the reliability and validity of the translated instrument.

3.2. Translation of the Questionnaire

First, the first and second researchers — both native Persian speakers and experts in this area of research — independently translated the original PCDEQ2 items, instructions, and response options into Persian. They then compared their translations and agreed upon a single reconciled version (18). Each translated item was subsequently reviewed by a bilingual sport psychologist to identify any discrepancies and to ensure that technical terms were accurately translated in line with the original meanings (19). In the next stage, the clarity of each item was assessed by 12 native Persian-speaking youth athletes aged 13 - 19 years, using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Very clear, 7 = Not clear at all). Revisions were made only to items receiving a score greater than 4. Finally, an experienced native English-speaking translator, fluent in Persian, back-translated the finalized Persian version into English. The first and second researchers compared the back-translated and original English versions, reaching full agreement on the final Persian translation (20). By adhering to this well-established and rigorous translation procedure, the researchers ensured the accuracy and conceptual equivalence of the final Persian version.

3.3. Participants

A total of 528 athletes participated in the study. The sample comprised 219 males (41.5%) and 309 females (58.5%), with ages ranging from 13 to 19 years. The participants were recruited from various sports clubs across Iran. Participants provided written informed consent (or parental consent for those under 18 years) and written assent before participating in the study. The inclusion criteria for participation included being a Persian-speaking athlete, aged between 13 and 19 years, and currently involved in competitive sports. Athletes were excluded if they had insufficient proficiency in Persian or were not actively engaged in sports. The final sample consisted of 528 youth athletes aged 13 - 19 years (219 males and 309 females). The sample size was determined in accordance with widely accepted methodological recommendations for psychometric and structural equation modeling (SEM) research. In such analyses, it is generally advised to include a minimum of around 200 participants or to maintain an adequate ratio of participants to questionnaire items to ensure stable and reliable parameter estimates. Considering that the PCDEQ2 includes several latent factors and items, the sample of 528 participants provided a sufficient basis for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), internal consistency assessment, and group comparisons [multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and discriminant analyses]. This sample size also allowed balanced representation across competitive levels and enhanced the precision and stability of the statistical results (Table 1).

| Variables | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 219 (41.5) |

| Female | 309 (58.5) |

| Age (y) | |

| 13 - 15 | 224 (42.4) |

| 15 - 17 | 185 (35) |

| 17 - 19 | 119 (22.5) |

| Number of sport disciplines | 15 |

| Individual sport | 205 (38.8) |

| Experience (y) | |

| 1 - 5 | 294 (55.7) |

| 5 - 10 | 169 (32) |

| More than 10 | 65 (12.3) |

| Competitive level | |

| Recreational | 143 (27.1) |

| Club | 316 (59.8) |

| National | 41 (7.8) |

| International | - |

3.4. Procedure

Data for this study were collected from active youth athletes who were members of sports clubs and secondary schools across several cities. Participants represented a range of individual and team sports. All data were obtained through self-administered online questionnaires distributed via secure survey links. The main instrument was the Persian version of the PCDEQ2, which measures key psychological characteristics related to talent development in sport. In addition, a brief demographic form was included to record participants’ age, gender, type of sport, years of experience, and level of competition. Responses were submitted anonymously, and no identifying personal information was collected. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee on Human Research of the Islamic Azad University of Isfahan (Khorasgan) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. The study procedures were described to the participants, and their informed consent to participate in the study was obtained online. In the case of those under 18 years, online informed consent was also obtained from their parents/guardians. Online PCDEQ2 Questionnaires were distributed to the 528 athletes between September and April to May 2021. The participants were asked to fill out the PCDEQ2 and provide demographic details (e.g., level of performance attained), but they were not required to write their names on the questionnaires. Participants rated each item according to their degree of agreement or disagreement using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Extremely unlikely, 6 = Extremely likely).

3.5. Data Analysis

The validity of the questionnaire was evaluated using SEM in AMOS. Factorial validity was assessed via the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Parsimonious Comparative Fit Index (PCFI), normed chi-square (CMIN/DF), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Following established cut-off criteria, CFI and TLI values > 0.90 indicate adequate fit and > 0.95 indicate good fit (21); RMSEA < 0.08 and SRMR < 0.06 represent adequate and good fit, respectively; PCFI > 0.50 and CMIN/DF < 5 indicate acceptable fit (21). Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with values ≥ 0.70 considered acceptable (22). To examine group differences based on competition level, MANOVA was conducted with significance set at P < 0.05. Discriminant function analysis was also performed to evaluate the prediction of group membership. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS Version 22.0 (23).

4. Results

The SEM was performed to confirm the PCDEQ2 (1). In this study, a seven-factor model was tested. Fit indices, including RMSEA = 0.056, TLI and CFI > 0.9, PCFI = .751, and CMIN/DF = 2.15 were obtained, which were all acceptable. Standardized factor loadings (from 0.4 to 0.74) were significant at the 0.001 level (Table 2). Data showed adequate fit to the 7-factor model: χ2 (3737) = 9522.86, CFI = 0.839, TLI = 0.818, RMSEA = 0.054, 90% CI (0.053, 0.056), PCFI = 0.682, CMIN/DF = 2.55, SRMR = 0.079. Evaluation of factor loadings showed that factor loadings of items 21, 50, 58, and 83 were smaller than 0.3, so these items were eliminated. Inspection of modification indices indicated that error terms for items 4 and 7 (χ2 = 59.44), 8 and 9 (χ2 = 118.88), 73 and 71 (χ2 = 84.34), as well as items 51 and 52 (χ2 = 104.35) had relatively large modification indices compared to the others. The measurement model was thus re-specified by having the above-mentioned pairs of error terms as correlated. The model fit of the specified model was improved: χ2 (3391) = 8455.593, CFI = 0.918, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.053, 90% CI (0.052, 0.055), PCFI = 0.712, CMIN/DF = 2.49, and SRMR = 0.078. Internal consistency reliability for the whole questionnaire was obtained using Cronbach's alpha (α = 0.89). All factors revealed internal reliability above the minimum recommendations of 0.70, ranging from 0.703 to 0.924.

| Factors | Low-level | High-level | Effect Size | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse response to failure | 3.27 ± 0.83 | 2.93 ± 0.82 | 0.412 | < 0.05 |

| Imagery and active preparation | 4.5 ± 0.91 | 4.94 ± 0.65 | 0.563 | < 0.01 |

| Self-directed control and management | 4.06 ± 0.89 | 4.34 ± 0.59 | 0.371 | < 0.05 |

| Perfectionistic tendencies | 3.57 ± 0.96 | 3.08 ± 0.72 | 0.582 | < 0.001 |

| Seeking and using social support | 4.17 ± 0.93 | 4.64 ± 0.73 | 0.55 | < 0.001 |

| Active coping | 4.22 ± 0.99 | 4.54 ± 0.505 | 0.407 | < 0.01 |

| Clinical indicators | 3.21 ± 0.99 | 2.73 ± 0.78 | 0.538 | < 0.01 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Responses were provided on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“very unlike me”) to 6 (“very like me”).

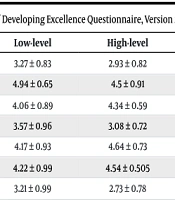

4.1. Competition Level

Next, we wished to compare the discriminant capability of the Persian version to those obtained with the original. The total number of the high-level and low-level athletes identified among the participants was 69 and 459, respectively. Consistent with previous studies (24, 25), those athletes who competed in various sports at national and international levels were defined as the high competitive level athletes, and those who competed at a recreational or club level were defined as low competitive level athletes. Based on previous research suggesting that certain athlete characteristics, such as competitive level, influence PCDE (12, 24-28), it was hypothesized that athletes at higher levels of competition have different psychological characteristics than athletes at lower levels of competition. Before the ANOVA analysis, since there were 69 athletes in the high levels of competition, the sample was randomly removed from low levels of competition to equal the number in the groups, and the analyses were performed with 138 samples (69 people in each group). Our findings supported this hypothesis.

As with the UK applications of the PCDEQ2, high-level and low-level athletes have different PCDE profiles (Table 3). A Mahalanobis distance was obtained, 58.19, which is less than the critical value of 61.3, indicating multivariate normality (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2013). We found a difference in PCDEQ between the groups high-level and low-level, [F (7, 130) = 4.55, P < 0.001, Wilks Lambda = 0.803, partial eta squared = 0.197]. Table 2 shows descriptive statistics of PCDEQ in two groups, effect sizes, and significance levels of differences between groups. Furthermore, we found a significant discriminant function of the PCDEQ (Wilks Lambda = 0.803, χ2 = 29.07, P < 0.001), with a canonical correlation of 0.444. The PCDEQ was able to correctly predict 66.7% (46 out of 69) of the high-level competition group members and 73.9% (51 out of 69) of the low-level competition group members; in total, 70.3% of the 138 participants could be correctly classified.

| Factors | Low-level | High-level | Effect Size | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse response to failure | 3.27 ± 0.83 | 2.93 ± 0.82 | 0.412 | < 0.05 |

| Imagery and active preparation | 4.94 ± 0.65 | 4.5 ± 0.91 | 0.563 | < 0.01 |

| Self-directed control and management | 4.06 ± 0.89 | 4.34 ± 0.59 | 0.371 | < 0.05 |

| Perfectionistic tendencies | 3.57 ± 0.96 | 3.08 ± 0.72 | 0.582 | < 0.001 |

| Seeking and using social support | 4.17 ± 0.93 | 4.64 ± 0.73 | 0.55 | < 0.001 |

| Active coping | 4.22 ± 0.99 | 4.54 ± 0.505 | 0.407 | < 0.01 |

| Clinical indicators | 3.21 ± 0.99 | 2.73 ± 0.78 | 0.538 | < 0.01 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Responses were provided on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“very unlike me”) to 6 (“very like me”).

To examine gender, sport type, and age invariance, first the unrestricted models were examined, and then the fit indices of the models with factor loading restrictions were compared with the unrestricted model in Table 4. The ∆χ2 values, which were calculated with the aim of the chi-square test of the constrained and unrestricted models, showed that the factor loadings (P = 0.234, ∆χ2 = 434.24) among girls and boys, the factor loadings in individual and team sports (P = 0.326, ∆χ2 = 355.79), and the factor loadings in age groups (P = 0.315, ∆χ2 = 370.445) are equal. Accordingly, the invariance of gender, sport type, and age in the psychological characteristics of the developing sports elite is confirmed.

| Factors | Individual | Team | Effect Size | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse response to failure | 3.25 ± 0.94 | 3.14 ± 0.92 | 0.12 | < 0.05 |

| Imagery and active preparation | 4.37 ± 0.88 | 4.9 ± 0.68 | 0.674 | < 0.001 |

| Self-directed control and management | 4.15 ± 0.67 | 4.37 ± 0.66 | 0.330 | < 0.001 |

| Perfectionistic tendencies | 3.49 ± 0.88 | 3.43 ± 0.85 | 0.069 | > 0.05 |

| Seeking and using social support | 4.27 ± 0.89 | 4.5 ± 0.71 | 0.285 | < 0.01 |

| Active coping | 4.27 ± 0.68 | 4.52 ± 0.61 | 0.387 | < 0.001 |

| Clinical indicators | 3.3 ± 0.81 | 2.89 ± 0.77 | 0.519 | < 0.001 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Responses were provided on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“very unlike me”) to 6 (“very like me”).

4.2. Other Mediating Factors: Gender and Sport Type

The differences between males and females in PCDEQ are presented in Table 4, and the differences between athletes in team and individual sports are presented in Table 5. As can be seen in Table 1, the number of sample people in the groups of male and female, as well as team and individual sports, are different, so the sample was randomly removed from the groups to equal the sample size in all groups (205 people in team and individual sports in each group and in women and men of each group, 219 people).

| Factors | Male | Female | Effect Size | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse response to failure | 3.23 ± 0.88 | 2.97 ± 0.83 | 0.304 | < 0.001 |

| Imagery and active preparation | 4.64 ± 0.81 | 4.95 ± 0.65 | 0.422 | < 0.001 |

| Self-directed control and management | 4.23 ± 0.68 | 4.44 ± 0.58 | 0.332 | < 0.001 |

| Perfectionistic tendencies | 3.45 ± 0.82 | 3.53 ± 0.902 | 0.093 | > 0.05 |

| Seeking and using social support | 4.26 ± 0.82 | 4.51 ± 0.74 | 0.320 | < 0.001 |

| Active coping | 4.22 ± 0.69 | 4.55 ± 0.56 | 0.525 | < 0.001 |

| Clinical indicators | 3.11 ± 0.86 | 2.8 ± 0.73 | 0.389 | < 0.001 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Responses were provided on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“very unlike me”) to 6 (“very like me”).

We found a difference in PCDEQ between team and individual sports, [F (7, 402) = 9.96, P < 0.001, Wilks Lambda = 0.852, partial eta squared = 0.148]. Table 3 shows descriptive statistics of PCDEQ in two groups, significance levels of differences between groups, and effect sizes. The results show that the difference between athletes in team and individual sports is obtained in significant dimensions except in dimensions adverse response to failure and perfectionistic tendencies. We also found a difference in PCDEQ between males and females, [F (7, 430) = 7.902, P < 0.001, Wilks Lambda = 0.886, partial eta squared = 0.114]. Descriptive statistics of PCDEQ in two groups, effect sizes, and significance levels of differences between groups are presented in Table 5.

5. Discussion

The need and usefulness for evidence-based PCDE in sport is clear. However, while PCDEQ2 has been translated into multiple languages to be used cross-culturally, as well as developed further psychometrically, so far no Persian version has been developed or validated. Neither has the cross-cultural validity of the underlying approach been checked. Accordingly, this scale validation and development were considered to be a critical step given the number of Persian-speaking countries with a robust interest in effective PCDEQ2 within sport. Firstly, the present research aimed to evaluate the validity and factor structure of the Persian version of the PCDEQ2. Results confirmed that the final Persian PCDEQ2 included 7 factors identical to the original English version. Factor 1: Adverse response to failure (items 1 - 21); factor 2: Imagery and active preparation (items 22 - 36); factor 3: Self-directed control and management (items 37 - 50); factor 4: Perfectionistic tendencies (items 51 - 60); factor 5: Seeking and using social support (items 61 - 69); factor 6: Active coping (items 70 - 79); factor 7: Clinical indicators (items 80 - 88). Four items were removed due to poor psychometric properties and cultural incompatibility. Item 50 was excluded because of a low factor loading and the negative interpretation of self-rewarding without achieving the goal within the Iranian culture. Item 21 demonstrated poor psychometric performance due to ambiguity in translation and the cultural interpretation of "not worrying" as indifference. Item 58 was also inconsistent with cultural values because of implicit judgment toward others and colloquial expressions that were difficult to translate. Finally, item 83 was removed due to gender sensitivity, response bias, and lack of alignment with the core constructs of the questionnaire. The removal of these items contributed to enhancing the cultural validity and conceptual coherence of the Persian version. The results obtained from this research revealed that the Persian PCDEQ2 is a valid and reliable tool that measures psychological characteristics among the Iranian sport’s talent population. Results showed the satisfactory reliability of the Persian talent.

With regard to our cross-cultural comparison, findings of this study were in agreement with the original study (1). Investigation of the psychometric properties of the Persian PCDEQ2 provided evidence of the adequate convergent validity and divergent validity of the resulting model. Though the internal reliability was a little less than that of the English PCDEQ2 (0.79 to 0.86) (29), all of the factors yielded internal reliability values (Cronbach's alpha) of greater than the minimum recommendations of 0.60, ranging from 0.602 to 0.761. Possibly the process of translation has led to a slight loss of meaning or misinterpretation of items, or items misinterpretation-related errors. Such behaviors or guessing items were more likely to happen because the participants in our study were a bit younger than in previous studies.

With regard to gender and sports type, the picture is still positive albeit a little more complex. There were several significant differences across gender and sports type; in contrast to research with the English version (30) indicating that practitioners should take care when using the tool as an applied instrument. Cultural factors may significantly influence the interpretation of psychological constructs such as social support and perfectionism among athletes. In Iranian society, which emphasizes collectivism and interdependence, social support is often deeply rooted in familial and communal relationships, potentially differing from the more individualistic perceptions prevalent in Western cultures. Similarly, perfectionism in Iranian athletes may be shaped by cultural expectations and social norms. Research indicates that Iranian male athletes may experience perfectionistic concerns differently, with factors like rumination contributing less to these concerns compared to their Western counterparts (31).

Several well-established theoretical frameworks support the interpretation of our findings regarding gender and sport-type differences measured by the PCDEQ2. Self-determination theory (32) emphasizes the importance of intrinsic motivation, autonomy, competence, and relatedness, highlighting how psychosocial environments shape athletes’ motivation and psychological development. This theory helps explain variations in social support and motivational processes between male and female athletes as well as between individual and team sports. Moreover, achievement goal theory (33) focuses on athletes’ goal orientations — mastery (task-oriented) versus performance (ego-oriented) — and their influence on responses to success and failure. Considering that individual and team sports often foster distinct motivational climates, this theory sheds light on the psychological profile differences identified by the PCDEQ2. Integrating these frameworks offers a comprehensive lens for understanding cultural, gender, and sport-specific psychological characteristics in the Iranian athletic context.

These cultural nuances suggest that the observed deviations in the factor structures and item responses of the PCDEQ2 may reflect the distinct cultural contexts of Iranian athletes. Consequently, practitioners and researchers should carefully consider these cultural influences when interpreting results and applying the PCDEQ2 across diverse populations. Importantly, further research is needed to directly compare Western and Persian athletes on key mediating factors, such as gender differences in clinical indicators and adverse responses to failure, as well as overall profile differences between individual and team sports. Such investigations could clarify the type and extent of psychosocial influences on young performers in these cultural contexts.

5.1. Conclusions

This study successfully translated and validated the Persian PCDEQ2, supporting its use in Persian-speaking research and applied settings as a formative tool to monitor and develop youth athletes’ psychological skills (11, 34). Cross-cultural comparisons indicate that both the instrument and the PCDE approach are largely robust, though subtle differences related to gender and sport type highlight the need for careful, context-specific interpretation. The Persian PCDEQ2 also provides a valuable resource for investigating the role of psychological characteristics in talent development and performance. However, as validation was conducted within an Iranian context, caution is advised when generalizing findings to other Persian-speaking populations.