1. Background

Unilateral spastic cerebral palsy (USCP), resulting from early neurological lesions, is characterized by sensory-motor deficits and spasticity that predominantly affect one side of the body (1, 2). In addition to limitations in movement, cerebral palsy (CP) may also cause cognitive, sensory, communicative, seizure-related, perceptual and behavioral disorders (3, 4). Brain injuries do not cause specific behavioral patterns, but associated motor deficits can significantly influence a child’s behavior (5, 6). Children exhibiting disabilities of the central nervous system are at increased risk for encountering behavioral difficulties (6). Behavioral difficulties are defined as socially inappropriate actions that interfere with the conduct of daily life (7). Such behaviors may encompass challenges with peer interactions, attention deficits, hyperactivity, emotional disturbances, increased dependency, social withdrawal, obstinacy, and antisocial tendencies (5). These issues, reported in 26% to 40% of children with CP, significantly impact personal and social interactions (8). Few studies have explored behavioral issues in children with CP. Voyer et al. found that even those with high motor function (GMFCS levels I-II) can experience significant social impairments alongside motor challenges (9). Schuengel et al. also reported that perceived motor ability, physical appearance, and self-worth were positively related to aggression (10). Children with CP may struggle to maintain peer relationships and a sense of belonging because they leave the classroom for supportive services and feel anxious about fitting in at school. Dababneh (11) associated physical appearance concerns in children with CP with social and behavioral problems, citing reduced mirror neuron activity. Mirror neurons, primarily found in the ventral premotor cortex and parietal lobe, are widely distributed throughout the cerebral cortex, forming what is known as the mirror neuron system (MNS) (4). These neurons are localized in regions of the brain that are associated with advanced perceptual, motor and cognitive functions (12). Given the importance of these factors, the implementation of new therapies is crucial for children with CP (11). While approximately 182 therapeutic interventions are available, common motor-based approaches include constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT), muscle strengthening programs, hippotherapy, and task-oriented training (4). Mirror visual feedback therapy (MVFT) is a modern, inexpensive, and effective option with no side effects, special equipment needs, or pain and can be easily performed without involving the affected limb (4, 13). It is believed to work by facilitating motor pathways, preventing learned disuse, and activating mirror neurons (14).

The MVFT is thought to work through the MNS, where visuomotor neurons are activated during observation, imagination, or execution of motor tasks (15, 16). Observing an action increases excitability in visual and somatosensory areas, potentially reflecting increased attention to resolve perceptual incongruence (17). This process is linked to awareness of sensory feedback/agency control (insular cortex) and movement monitoring (DLPFC) (18, 19). Furthermore, increased activity in the posterior parietal and cingulate cortex suggests increased attentional demands. The posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) plays a role in cognitive control (12). Observation also increases excitability in the primary motor cortex (M1) and related muscle groups, aiding cortical reorganization crucial for hand recovery (20, 21). Children with USCP often develop "learned non-use" of the affected hand, leading to a preference for the unaffected side and further functional decline. The MVFT counteracts this by encouraging use of the impaired hand and reducing neglect. Applying MVFT to the less-affected hand has been shown to significantly improve gross motor performance in children with USCP (22). Although MVFT is known to improve motor function, its effects on behavioral issues common yet often overlooked in children with CP remain unclear. Addressing these behaviors is essential for enhancing therapeutic outcomes and family quality of life.

2. Objectives

The present study investigated the impact of MVFT on behavioral problems in children with USCP.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

A total of 14 patients with USCP participated in this between-group, randomized, counterbalanced, single-blind, and sham-controlled research. The sample size was calculated via G*Power software (version 3.1.9.2, Kiel, Germany) with the following parameters: Test family = F tests; statistical test = ANOVA: Repeated measures, between groups; error probability α = 0.05; statistical power (1-β) = 0.80; effect size = 1.14 (23). The software recommended at least 6 participants per group. Considering a 20% dropout rate, 7 participants were selected for each group, which were equally divided into mirror training and no-mirror training groups. In this research, the inclusion criteria for children with USCP (mean age 9 years) referred to the Kermanshah Medical Center were reviewed. The inclusion criteria required sufficient trunk control for independent sitting, along with adequate verbal and cognitive abilities (including concentration, working memory, and attention). Exclusion criteria consisted of pain or prior surgery in the affected hand, epilepsy, visual impairments, or cardiac issues. These strict criteria significantly reduced the number of eligible participants (22). Finally, 14 children were selected via convenience sampling and randomly divided into two groups, i.e., the MVFT or therapy group (7 children) and the control group or no mirror group (7 children).

3.2. Procedure

The study was conducted at Sepid Neurology Clinic in Kermanshah, Iran. Each participant underwent a total of 18 sessions. The first session served as an orientation, during which demographic and clinical data were collected using the Personal Information Questionnaire and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Participants were also familiarized with the motor assessment and intervention procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participants under the age of 16 prior to any formal evaluation. During the intervention, participants were instructed to focus for one to two minutes on the mirror image of their unaffected hand, aiming to visualize it as their affected limb behind the mirror. Treatment commenced once the participants perceived the mirror image as representing their affected limb.

The MVFT was administered over six weeks, with three 30-minute sessions per week. During the first two to three weeks, participants performed simple motor exercises — including finger, wrist, and elbow flexion/extension; forearm rotation; and finger stretching. They practiced unilateral, bilateral, affected-hand-guided, and therapist-guided movements (approximately 15 repetitions each). The movement that produced the strongest mirror illusion was selected for use in subsequent sessions. Training then progressed to more complex tasks, such as ball transfers, dumbbell wrist flexion/extension, forearm pronation/supination, palmar and finger ball presses, and ball grasping (Figure 1).

During MVFT sessions, participants performed specific exercises with their unaffected hand. A key element of this therapy was the strategic placement of a mirror precisely in the sagittal plane between the two hands. This setup created a visual illusion intended to stimulate the brain: Participants could see the actual movement of their unaffected hand while simultaneously viewing its mirror reflection, which was carefully aligned with the hidden affected hand. This visual feedback was designed to create the powerful impression that the affected hand was moving symmetrically and smoothly. Consequently, participants were motivated to consciously attempt to mimic the observed movements with their affected hand, thereby promoting the feeling of coordinated bimanual motion. This process aims to facilitate neural plasticity and improve motor function in the affected limb by tricking the brain into perceiving improved movement in the impaired hand (22, 24-26).

To minimize the influence of daily variations in bodily function, all training sessions were conducted at the same time of day for each participant, controlling for potential circadian effects. The control group performed identical motor tasks using their unaffected hand, but without the use of a mirror. The two groups attended sessions on separate days to prevent awareness of the alternative intervention, and parents were not informed of the specific exercise details to reduce the risk of bias.

3.3. Measurement of Behavioral Problems

The SDQ, a screening tool for behavioral problems in children and adolescents aged 4 to 16 years, was used to assess participants before and after the intervention. Designed by Robert Goodman in England in 1997, the SDQ has parent, teacher, and self-report versions (the latter for ages 11 - 16). The questionnaire consists of 25 items divided into five scales, each containing five items: Emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, peer relationship problems, and prosocial behavior. The parent-report version was used in this study. Respondents rated each item as "not true" (scoring 0), "somewhat true" (scoring 1), or "certainly true" (scoring 2). Scale scores are calculated by summing the scores of the five items within each scale, resulting in a range of 0 to 10 for each subscale. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for the parent SDQ in this study was α = 0.7 (27, 28).

3.4. Data Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD). The normality of the data was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. A two-way repeated-measures ANOVA (2 groups × 2 time points) was employed to analyze the SDQ scores. In the case of a significant group × time interaction, Bonferroni post hoc tests were used for pairwise comparisons.

For the ANOVA, effect sizes were reported as partial eta-squared (ηp2) and interpreted as follows: Small (0.01 - 0.059), medium (0.06 - 0.139), or large (≥ 0.14). For pairwise comparisons, effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d and classified as small (0.20 - 0.49), medium (0.50 - 0.79), or large (≥ 0.80). The percentage change (Δ%) from pretest to posttest was also calculated for each condition.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with the significance level set at P < 0.05. Figures were prepared using Microsoft Excel.

4. Results

The M ± SDs of the participants’ scores by group and measurement time period are presented in Table 1.

| Subscales | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental | Control | |||

| Pretest | Posttest | Pretest | Posttest | |

| Emotional symptoms | 4.71 ± 0.95 | 3.14 ± 1.06 | 4.57 ± 0.78 | 4.57 ± 0.78 |

| Conduct problems | 2.42 ± 0.97 | 2.14 ± 0.69 | 2.57 ± 0.97 | 2.42 ± 0.97 |

| Hyperactivity problems | 4.14 ± 1.34 | 2.42 ± 0.97 | 4.00 ± 1.29 | 3.85 ±1.34 |

| Peer problems | 3.42 ± 0.78 | 1.71 ± 0.48 | 3.28 ± 0.75 | 3.14 ± 0.89 |

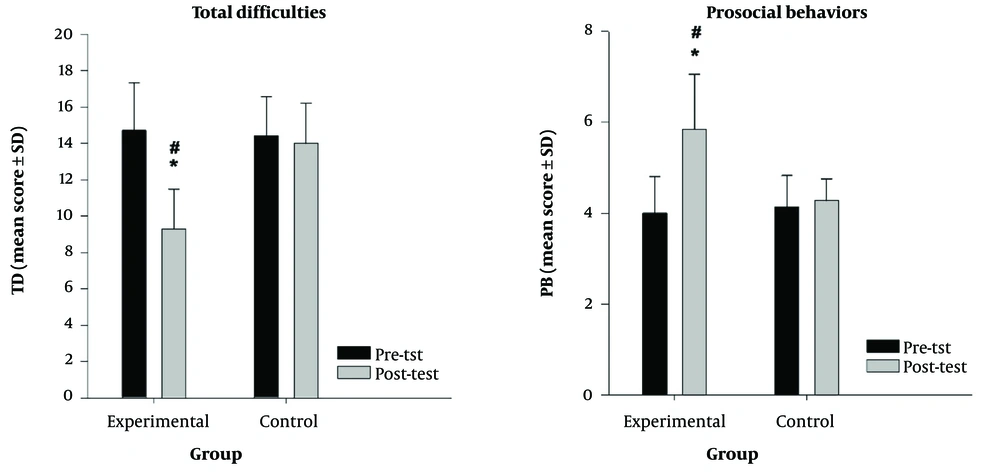

| TD | 14.71 ± 2.62 | 9.28 ± 2.21 | 14.42 ± 2.14 | 14.00 ± 2.23 |

| BP | 4.00 ± 0.81 | 5.85 ± 1.21 | 4.14 ± 0.69 | 4.28 ± 0.48 |

Abbreviations: TD, total difficulties; PB, prosocial behaviors.

a Values are expressed as M ± SD.

The results of the mixed analysis of variance revealed that for the total difficulties (TD) variable, the interaction effects of group × time [F(1.12) = 54.04, P < 0.001] and time [F(1.12) = 74.16, P < 0.001] were statistically significant, whereas the main effect of group [F(1.12) = 3.465, P > 0.001] was not statistically significant. The simple effects of group and time were analyzed separately because of the significance of the interaction effect. The results revealed that in the pretest phase, there was no significant difference in the average TD between the two intervention groups (P > 0.05). Compared with the control group, the experimental group presented a significant reduction in TD (P < 0.001, dav = 2.12, Δ = -40.5%) at the posttest. Pairwise comparisons revealed that TD improved significantly from pretest to postintervention (P < 0.001, dav = 2.24, Δ = -36.91%) in the experimental group.

Additionally, the results of the mixed analysis of variance revealed that for the prosocial behaviors (PB) variable, the interaction effects of group × time [F(1.12) = 33.23, P < 0.001] and time [F(1.12) = 45.23, P < 0.001] were statistically significant, whereas the main effect of group [F(1.12) = 3.465, P > 0.001] was not statistically significant. The simple effects of group and time were analyzed separately because of the significance of the interaction effect. The results revealed that in the pretest phase, there was no significant difference in the average PB between the two intervention groups (P > 0.05). The PB was also significantly greater in the experimental group than in the control group (P = 0.008, dav = 1.86, Δ = 0.31%) at the posttest. Pairwise comparisons revealed that PB improved significantly from pretest to postintervention (P < 0.001, dav = 1.01, Δ = +46.25%) in the experimental group (Figure 2).

5. Discussion

This study is the first to examine the effect of MVFT on behavioral problems in children with USCP. The results demonstrated that MVFT significantly reduces behavioral problems and increases PB. These findings are consistent with Whittingham et al. (29), who reported that stepping stones triple P (SSTP) reduces behavioral problems in children with CP, with additional benefits from acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). While behavioral interventions directly improve conduct, persistent motor impairments may contribute to problem recurrence, as supported by Dababneh (11), who linked social-behavioral difficulties in CP to concerns about physical appearance and reduced mirror neuron activity. In contrast, the current study applied MVFT to address motor dysfunction directly.

Supporting this approach, Farzamfar et al. (22) showed that MVFT enhances motor performance in hemiplegia. Proposed mechanisms include reduced visual attention to the affected limb (30), enhanced visual feedback, and MNS activation (31). These processes may facilitate corticospinal tract activation and rebalance interhemispheric inhibition, thereby improving motor function (20). Observing the unaffected hand’s mirror image generates motor imagery of the affected hand, activating the MNS. Buccino et al. (32) further indicated that MNS engagement stimulates the M1 cortex and reactivates motor regions related to observed actions, ultimately improving motor skills (6, 33, 34).

Sankar and Gordon et al. (35, 36) used the "Constraint Induced Movement Therapy (CIMT)" strategy to improve the affected hand of hemiplegic children. This involves physical constraint of the unaffected hand to increase the use of the affected hand, which is associated with pain in the affected limb. Yamaguchi et al. reported that while pain intensity appears to be associated with behavioral and emotional problems in children, pain anxiety may still be more strongly associated (7). The experience of pain appears to disrupt activities associated with the default mode network (DMN) and with cognitive performance (37). As a result, in the present research, focusing on exercise in the mirror by a healthy hand reduced pain anxiety in the patient and thus improved behavioral problems. Early rehabilitation on the affected side and the use of a healthy limb with the aim of stimulating the affected side stimulate the residual involved tissue to compensate for functional deficits and provide a better position for tissue reconstruction and improvement of motor and behavioral problems (38).

Additionally, mirror neurons support emotion, social interaction, and empathy (39). The MNS is essential for social communication, empathy, imitation, and action understanding, illustrating how motor function influences behavior (40). This system is part of a broader network affecting behavior, especially emotional behavior. The cerebral cortex consists of specialized regions interconnected by complex axonal pathways (41). The DMN includes subsystems linked by hubs (42), such as the PCC, insular cortex, precuneus, and parietal and prefrontal cortices (41). These regions are highly interconnected (43), with the PCC acting as an information hub involved in cognitive control (12). The PCC subregions interact with executive, attentional, motor, language, and DMNs (44). Thus, MVFT improves motor function and reduces behavioral problems (11, 45). Cummins et al. (46) found that poor motor performance reduces a child’s self-esteem, increasing peer problems, potentially due to negative peer attitudes toward children with USCP (8, 47). Improved motor function and physical appearance may help reduce these peer issues.

Schuengel et al. and Sigurdardottir highlighted that motor impairments restrict activities in young children, leading to frustration, social isolation, and maladaptive behaviors. Improving motor function in children with USCP reduces behavioral problems (10, 48), likely by decreasing frustration, promoting social inclusion, and reducing maladaptive behaviors. While MVFT shows promise in enhancing motor skills and reducing behavioral issues, it remains unclear whether these behavioral benefits stem directly from motor improvement or from a more direct neuromodulatory effect on behavior-related neural pathways. Future studies should incorporate brain imaging to precisely identify the brain regions modulated by MVFT and clarify whether it acts primarily on motor networks or directly influences behavioral and emotional circuits.

This study had several limitations. Some patients had difficulty focusing on the healthy limb’s image, which may have affected the results. Future studies should use more engaging exercises and shorter sessions with frequent breaks to address this. Another limitation was patient distraction with the mirror image and difficulty locating the affected hand behind it, which reduced treatment efficacy. Using a mirror box to conceal the affected hand is recommended for future research. Furthermore, the study focused on children aged 6 - 12, a critical period for prefrontal cortex development. Age-related physiological changes, such as decreased synaptic plasticity, can reduce the brain’s capacity for plasticity, as shown by PAS protocols. Since the intensity of PAS-induced plasticity is greater in younger individuals (49, 50), understanding the effect of age on MVFT outcomes is crucial. Future research should therefore include older age groups and utilize the self-report version of the SDQ to identify potential age-related differences in response.

The MVFT may reduce behavioral challenges in children with USCP. Motor training using a mirror shows promise as a valuable therapeutic intervention for improving behavioral outcomes in this population.