1. Background

Motor skills are essential to children’s physical and cognitive development, supporting critical abilities such as coordination, focus, and self-regulation (1, 2). Engaging children in structured activities including sports, games, and targeted motor tasks encourages them to perform goal-oriented actions and enhances their executive functions (3). These activities contribute to skills such as spatial awareness and problem-solving, while fostering confidence and social skills through group play and cooperative actions (4-6). This foundational development prepares children for academic and social success by strengthening both physical and cognitive abilities.

Cup stacking, a popular skill-based activity, has gained attention for its benefits to hand-eye coordination, bilateral coordination, and reaction time. In addition to physical benefits, cup stacking promotes mental skills such as concentration and memory (7), making it an ideal activity for young learners.

Structured cup stacking activities have been shown to positively influence reaction time in children. A study involving second-grade students demonstrated significant improvements in both hand-eye coordination and reaction time after participating in a five-week cup stacking program compared to a control group that did not engage in this activity (8). Another study examined the effects of a three-week cup stacking instructional unit on children in grades 2 and 4 but found no significant differences in reaction times between the experimental and control groups (9). However, a different study indicated that practicing cup stacking, regardless of the practice structure (massed or distributed), led to improved reaction times after just one hour of practice (10).

Self-talk in research is commonly divided into motivational and instructional types. Motivational self-talk enhances performance and learning by boosting self-confidence, motivation, reducing anxiety, and fostering positive moods. Instructional self-talk improves focus, technical information retention, and executive strategies, thereby also enhancing performance and learning (11). Baniasadi et al. demonstrated that participants who engaged in instructional and motivational self-talk significantly outperformed the control group in basketball throw accuracy (11). Perkos et al. found that instructional self-talk is an effective tool for skill acquisition and performance enhancement, particularly for skills that are low in complexity, such as those involved in basketball (12). Zetou et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of instructional self-talk in enhancing the backstroke performance of young swimmers. The results indicated that participants who utilized instructional self-talk showed greater improvements in performance and skill acquisition compared to those who received feedback through traditional teaching methods (13). Anderson et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of instructional self-talk in enhancing the overhand throw performance (14). Bandura’s self-efficacy theory suggests that self-talk enhances athletes’ performance by boosting their self-efficacy, a sense of competence and ability to handle challenges. High self-efficacy leads to greater persistence and better performance in tasks (15). Instructional self-talk has also been shown to improve reaction time and fine motor skill performance, especially in structured tasks like cup stacking. By directing attention to key technical elements, it enhances motor execution and cognitive control, making it an effective strategy for both skill acquisition and speed improvement (16-19).

The shift toward virtual learning, particularly accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has presented both challenges and opportunities in motor skill instruction. While traditional face-to-face methods provide direct feedback and physical interaction, virtual environments require innovative strategies to maintain engagement and effectiveness. One such strategy is instructional self-talk, which can help bridge the gap by enhancing focus and self-guided performance even in the absence of in-person coaching. With the advancement of educational technology, virtual learning has become a widely accessible option for teaching motor and cognitive skills. Virtual environments offer flexible, adaptive, and often engaging methods to deliver instruction, allowing children to practice and refine skills remotely (20). However, further research is needed to determine how techniques like self-talk can be integrated into virtual instruction for optimal learning outcomes.

While self-talk has been studied extensively in sports and cognitive tasks, there is limited research on its effectiveness in teaching motor skills such as cup stacking. Understanding how self-talk might enhance skill acquisition in activities that demand coordination and timing could provide valuable insights for educators and coaches. As previously mentioned, with the growing prevalence of virtual education, there is a need for studies that examine the application of strategies such as self-talk within online learning environments. In this context, the present study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when in-person classes were not feasible and educational activities were held virtually. Consequently, the intervention was specifically designed and implemented for a virtual instructional setting. In this study, we sought to answer the following research question: To what extent does instructional self-talk influence the enhancement of cup stacking skills and reaction time in children within virtual learning environments?

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of instructional self-talk in enhancing motor skill performance among children. Specifically, it sought to explore how this cognitive strategy contributes to the development of hand-eye coordination, bilateral coordination, and reaction time during a structured motor task. Additionally, the study aimed to examine the potential of integrating self-talk techniques into virtual learning environments to optimize motor skill acquisition in young learners. It was hypothesized that instructional self-talk would improve both cup stacking performance and reaction time among children participating in virtual learning environments.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

This semi-experimental study involved 30 fifth-grade male students selected via convenience sampling according to the inclusion criteria: Age 9 - 11 years, access to a mobile device and stable internet, parental consent, possession of a standard set of stacking cups and sufficient practice space at home, normal or corrected vision and hearing, no history of neurological, psychological, or musculoskeletal disorders, and general health sufficient to safely perform physical activity. Exclusion criteria included missing more than two training sessions, incomplete pre- or post-test assessments, or any illness or injury arising during the study that could affect performance.

A priori power analysis using G*POWER 3.1 indicated a minimum sample of 29 participants (effect size = 0.7, α = 0.05, power = 0.95, two groups), and 30 participants were recruited to account for potential attrition. Participants were randomly assigned to the instructional self-talk or control group using a simple randomization procedure in Microsoft Excel. Each participant received a unique identification number, and allocation was performed alternately based on the sorted list. Randomization and allocation concealment were managed by an independent researcher using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, which were opened only after baseline assessments.

3.2. Apparatus and Task

3.2.1. Reaction Time Measurement

Reaction time was measured using a computerized version of the Johnson-Nelson reaction time test, as adapted by Udermann et al. This test assessed simple reaction time, requiring participants to respond as quickly as possible to a single, pre-determined visual stimulus.

Participants were seated comfortably, with their dominant finger resting on a designated response button connected to the computer. Following a variable preparatory period, a visual stimulus (e.g., a light) was presented on the computer screen. Participants were instructed to remove their finger from the response button as rapidly as possible upon detection of the stimulus. The time elapsed between stimulus onset and the participant’s response was recorded as reaction time in milliseconds (ms) by the computer software (8). Each participant completed the reaction time test three times, and the average of the three trials was recorded as their final reaction time score.

3.2.2. Cup Stacking Skill

Participants in both groups received instruction and practice in cup stacking over a period of four weeks, with two 60-minute virtual sessions per week (total of eight sessions). These sessions were integrated into a structured program delivered via the Shad social network. Each session began with a brief demonstration video (3 - 5 minutes) showcasing cup stacking techniques, followed by individual practice. A progressive curriculum was followed, requiring participants to use both hands as they advanced from basic three-stack formations to more complex stacking patterns (Figure 1).

Cup stacking time was measured using a simple model as a pre-test and post-test. This was done by asking participants to stack the cups in a specific order and recording the time taken to complete the stacking. This measurement was done to evaluate the improvement of participants’ cup stacking skill during the study period. As cup stacking is widely used as an assessment tool for motor coordination and dexterity, several studies support its effectiveness. For example, Udermann et al. demonstrated the positive impact of cup stacking on hand-eye coordination and reaction time in second-grade students. Furthermore, Michel and Kargruber reported significant improvements in motor skills among children engaging in manual dexterity training, which included cup stacking exercises. These studies validate the use of cup stacking as a reliable and standardized measure of motor coordination (8, 21).

3.3. Procedure

After obtaining approval from the school principal, initial coordination was made to introduce the study objectives and procedures to parents. An informational meeting was held in the school gym, where the purpose of the research, the implementation process, and the virtual training format using the Shad educational platform were thoroughly explained. Parents who agreed for their children to participate provided written consent. Each participating child received a standard set of stacking cups, and the instructor demonstrated the correct stacking techniques in person. Twenty-four hours later, a pre-test was conducted to assess participants’ baseline cup stacking performance and reaction time.

Following the pre-test, the four-week virtual cup stacking program was implemented via the Shad platform. The program consisted of two 60-minute sessions per week. At the scheduled time, participants logged into the virtual environment, watched a short (3 - 5 minute) wordless instructional video demonstrating cup stacking techniques, and then practiced independently at home for the remainder of the session. Throughout the sessions, participants were able to communicate with the researcher through the platform to ask questions or receive feedback.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The self-talk group was instructed to use the verbal cue “with the right hand to the right, with the left hand to the left” while practicing, whereas the control group performed the same tasks without verbal cues. To ensure adherence to the self-talk protocol, parents in the self-talk group completed a simple weekly observation checklist indicating whether their child consistently used the assigned verbal cue. These reports were submitted via the Shad platform. After completing the four-week program, all participants returned to the school gym for post-test assessments.

3.4. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® 26.0. The paired t-test and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were applied to analyze the data.

4. Results

Table 1 presents the means and standard deviations of demographic variables for the two groups. Independent t-tests showed no significant differences between groups in terms of age, weight, or height (P > 0.05). The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed normal data distribution (P > 0.05). Levene’s test and homogeneity of regression slopes were met, allowing ANCOVA to be used.

| Characteristics | Self-talk Group (n = 15) | Control Group (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 9.70 ± 1.33 | 9.40 ± 1.34 |

| Weight (kg) | 32.60 ± 2.98 | 32.90 ± 4.06 |

| Height (cm) | 138.90 ± 3.63 | 137.50 ± 4.60 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

The ANCOVA results revealed a significant effect of group on post-test cup stacking performance, F (1, 27) = 32.44, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.55, and reaction time, F (1, 27) = 26.53, P < 0.001, η2 = 0.69, indicating large effect sizes based on Cohen’s (1988) guidelines.

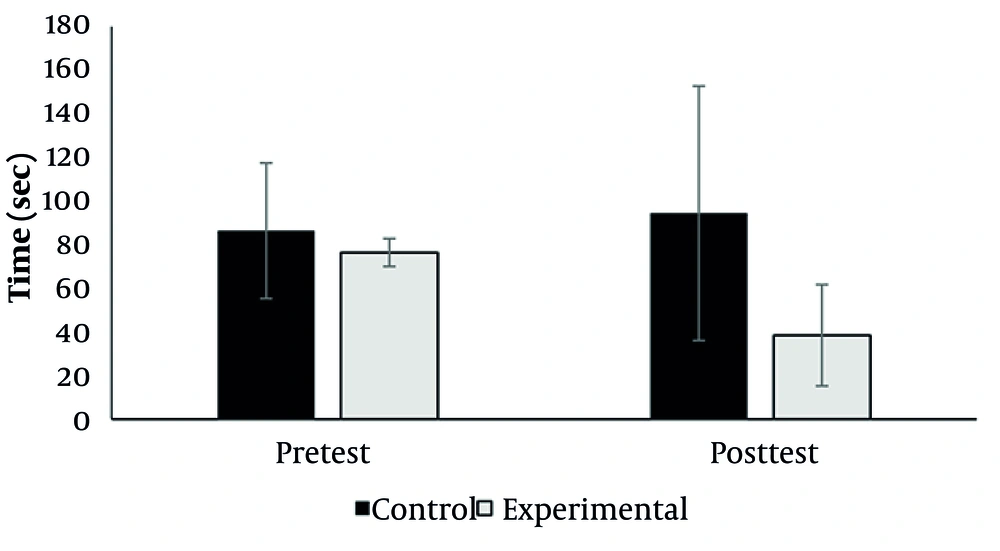

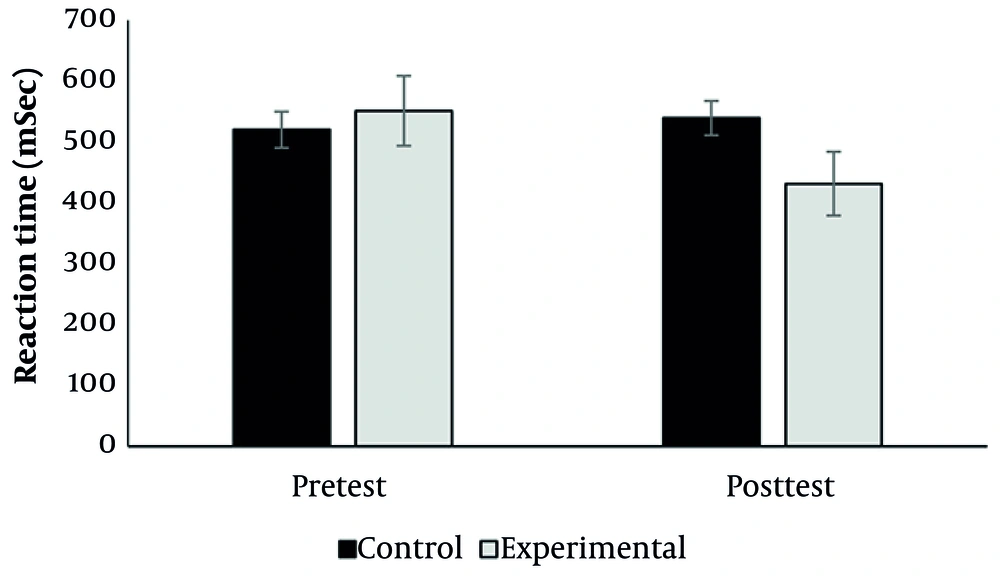

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the performance differences in cup stacking and reaction time between pre- and post-tests in both groups. Paired-sample t-tests showed a significant improvement in cup stacking time for the self-talk group, t (14) = -6.11, P = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.58, but not for the control group, t (14) = 0.83, P = 0.42, Cohen’s d = -0.11. Similarly, reaction time improved significantly in the self-talk group, t (14) = 5.71, P = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 2.39, while no significant change occurred in the control group, t (14) = -1.27, P = 0.22, Cohen’s d = -0.23.

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the effect of instructional self-talk on improving cup stacking performance and reaction time in children within a virtual learning environment. The findings provide strong evidence that instructional self-talk serves as an effective strategy for enhancing both motor skill execution and reaction time among children.

The role of instructional self-talk in motor skill learning has been well-documented, and our findings align with this growing body of evidence. For example, Perkos et al. demonstrated that instructional self-talk significantly improves motor performance, attentional focus, and cognitive control in children and young athletes (12). Studies suggest that both motivational and instructional self-talk contribute to the acquisition, retention, and execution of motor skills by helping learners focus on key task elements while reinforcing confidence and persistence. For instance, Bakhtiari et al. demonstrated that instructional self-talk significantly improved overarm throwing skills in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, particularly in skill acquisition and retention (22). Likewise, Nasiri and Shahbazi found that motivational self-talk enhanced the retention of tennis ball-throwing skills in young students by promoting sustained attention and resilience during practice (23). These findings support the idea that self-talk fosters both cognitive engagement and motor control, leading to better performance outcomes.

However, some research suggests that the effectiveness of self-talk may depend on task complexity and familiarity. For example, Santos Ferreira et al. found that self-talk had no significant effect on the retention or transfer of forehand skills in beginner tennis players, suggesting that the benefits of self-talk might vary depending on the skill type and the learner’s proficiency level (24). In contrast, studies in more structured motor learning contexts, such as Zetou et al. (13) in Tae-kwon-do, have shown that instructional self-talk enhances skill acquisition while also boosting cognitive control and self-confidence in young athletes. These contrasting findings underscore the importance of contextual factors in the effectiveness of instructional self-talk. While our study demonstrated positive effects in a relatively simple and structured task (cup stacking) among typically developing children, the lack of effect observed by Santos Ferreira et al. (24) in beginner tennis players suggests that task complexity, learner familiarity, and the nature of the motor task may influence the degree to which self-talk interventions are effective. Moreover, individual differences such as age, cognitive development, and prior experience may also moderate the impact of instructional self-talk. Therefore, while our findings support the utility of self-talk in enhancing motor learning and reaction time, they should be interpreted within the specific context of the task and population studied. Future research should further explore these moderating variables to better understand the conditions under which instructional self-talk is most beneficial.

Our findings align with these studies, particularly those emphasizing the positive effects of instructional self-talk on skill acquisition and reaction time improvement. Similar to Bakhtiari et al. (22) and Zetou et al., our study demonstrates that self-talk serves as an effective cognitive strategy for enhancing motor performance in children (13). Additionally, our results suggest that self-talk may be particularly beneficial for structured, sequential tasks like cup stacking, where precision, coordination, and reaction time are key factors.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that self-talk interventions, particularly instructional self-talk, lead to significant improvements in motor skill performance among children. For example, research on overarm throwing and soccer skills has shown that children who used self-talk exhibited greater performance gains compared to those in control groups (17, 22, 25). These findings highlight the role of self-talk in enhancing motor coordination, accuracy, and execution speed (25). Beyond initial skill acquisition, self-talk also contributes to long-term skill retention. Studies suggest that learners who employ self-talk strategies not only master new motor skills more effectively but also maintain their proficiency over time. This indicates that self-talk fosters deeper cognitive and motor engagement, reinforcing learned behaviors and improving consistency in performance. These findings align with our study’s results, which showed that self-talk significantly improved children’s cup stacking performance. The observed enhancements in both skill execution and reaction time further support the notion that self-talk serves as an effective cognitive strategy for motor learning.

Instructional self-talk helps structure thoughts and refine technique, making it particularly useful for tasks that require fine motor skills. Research has shown that instructional self-talk enhances performance by improving movement precision and increasing top-down control over motor actions (16, 26). By guiding attention toward task-relevant cues, it facilitates more efficient motor execution and learning.

Although self-talk was not explicitly applied during the reaction time assessment, it was systematically integrated into the cup stacking practice, which requires quick motor responses and attentional control. Therefore, the observed improvements in reaction time may reflect a transfer effect of enhanced cognitive-motor engagement facilitated by instructional self-talk during the structured motor training (8, 9). However, it is important to note that the current study did not directly measure self-talk usage during the reaction time task itself. Therefore, the observed improvements in reaction time should be interpreted cautiously, as they may be mediated by indirect cognitive mechanisms such as increased attentional control or general task engagement rather than a direct effect of self-talk. Future research with experimental designs incorporating control conditions for cognitive-motor transfer is needed to clarify the precise nature of this relationship.

Recent theoretical models also support the role of self-talk in enhancing cognitive processing speed. For instance, the cognitive architecture for inner speech (27), accumulator models of decision-making (28), and the theory of thought self-leadership (29) all suggest that internal dialogue can streamline information processing and improve reaction time through enhanced attentional control and cognitive efficiency.

The use of a virtual learning platform, such as the Shad network, demonstrated notable potential for motor skill instruction in children. This approach allowed for structured, repeated exposure to skill demonstrations while enabling remote supervision and parent involvement. Particularly during periods when in-person instruction is limited — such as during pandemics or in geographically isolated regions — virtual platforms can offer a viable alternative for delivering motor learning interventions. Moreover, the asynchronous format allowed learners to practice at their own pace, potentially reducing anxiety and improving focus. These findings highlight the adaptability and scalability of virtual learning environments for motor behavior education in young populations.

These findings reinforce the recommendation that educators and coaches incorporate self-talk techniques into training programs to enhance motor learning, attention, and skill retention in children. The results indicate that self-talk strategies effectively optimize motor skill development, especially in tasks requiring coordination, speed, and focus. Future studies should investigate the underlying mechanisms by which self-talk influences motor performance and compare the efficacy of various self-talk approaches. Additionally, examining the interaction between task complexity, learner experience, and self-talk type across different ages and learning contexts would provide valuable insights.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings of this study provide evidence supporting the effectiveness of self-talk as an intervention to improve cup stacking skills in children. Statistically significant improvements and large effect sizes were observed in both cup stacking and reaction time tasks, particularly highlighting the role of self-talk in enhancing motor coordination and task performance. While the results suggest that self-talk may also contribute to faster reaction times, this effect could be mediated by indirect cognitive mechanisms such as improved attention and task readiness. Given that self-talk was not applied during the actual reaction time task, further research is needed to directly investigate the potential transfer effects of self-talk on cognitive-motor performance.

5.2. Limitations and Generalizability

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. First, the relatively small and homogeneous sample — comprising only typically developing fifth-grade boys from a single school — limits the generalizability of the results to broader populations such as girls, younger or older children, or those with developmental or motor difficulties. Second, the study focused on a simple, well-structured motor task (cup stacking), which may not represent the complexity of real-world or sport-specific motor skills. Thus, the observed benefits of instructional self-talk might not directly translate to more complex or open-ended motor activities. Third, the reliance on parental reports to monitor self-talk adherence during home practice may have introduced potential reporting bias. Fourth, only immediate post-test outcomes were assessed; long-term retention and transfer of learning were not examined. Future research should include follow-up testing to evaluate the durability of self-talk effects. Finally, the relatively large effect size (d = 0.7) used for sample size estimation, while based on prior literature (30), may have influenced statistical power and the precision of effect estimates. Despite these limitations, the study provides promising evidence for the use of instructional self-talk in enhancing motor learning and reaction time among children in virtual learning environments. Nevertheless, future studies should replicate these findings in larger, more diverse samples and across different motor skills to strengthen external validity.