1. Background

Low back pain (LBP) affects approximately 80% of the general population at least once in their lifetime. Recent research indicates chronic LBP is associated with altered lumbosacral proprioception and postural balance (1-3). Furthermore, changes in proprioceptive processing for postural control such as reduced reliance on lumbar proprioceptive inputs and compensatory dependence on ankle proprioception have been observed in individuals with non-specific low back pain (NSLBP) (4).

Most studies have reported that individuals with NSLBP exhibit more significant postural sway during bipedal standing than healthy individuals (5, 6). The relationship between balance ability and proprioceptive ability is relatively straightforward, as feedback from muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs is used to maintain balance when visual input is removed (7). Proprioception is important in controlling a specific posture and can also be affected in a kinetic chain by changes in the posture or movement control of adjacent segments (8). The NSLBP can affect the neuromuscular function of patients. These functional impairments can be associated with reduced performance and gait speed, irregular movement patterns, and decreased coordination in these individuals (9). The ankle is significant among the body’s joints due to its weight-bearing capacity and range of motion (10). In individuals with LBP, balance, and postural control are maintained through a rigid stabilization strategy centered on the ankle, leading to greater oscillations in the ankle and foot regions and potentially heightened activity in the muscles responsible for ankle joint control (1).

Studies indicate that athletes experience a higher prevalence of LBP than the general population (11-13). Balance impairment in these individuals is thought to stem from deficits in the musculoskeletal and neuromuscular systems, including compromised lumbar proprioception and delayed muscle response, ultimately leading to reduced lumbar stability (14). Based on our knowledge there are few studies on disorders of proprioception of ankle and dynamic balance in athletes with NSLBP.

Most studies have evaluated balance and proprioception of the lower extremities mainly in non-athlete persons with NSLBP. Given that athletes face different and altered conditions of proprioception and balance, therefore we aimed to compare the dynamic balance and proprioception of the ankle joint in athletes with and without NSLBP.

2. Objectives

Assessing the accuracy of proprioception and dynamic balance of athletes with NSLBP to detect the impact of NSLBP on these two factors can provide researchers with more accurate information about the importance of controlling back pain and preventing sports injuries that occur secondary to back pain.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

The subjects were selected among male athletes in football, futsal, volleyball, and basketball players, aged 18 to 35 years. Participants (N = 30 based on G-power) entered the study in two groups with and without NSLBP (13, 15). The inclusion criteria for all subjects included membership in league for at least three years and three training sessions per week (12), with a pain of less than or equal to 3 out of 10 on the VAS Scale (5, 16, 17), no musculoskeletal problems in the lower extremities (17), no apparent postural abnormalities based on the New York body posture assessment tool for both groups (12, 17), the absence of any movement restrictions in the dominant ankle joint, and no history of concussion in the past 3 months for both groups (5, 18). The demographic information of the research subjects is presented in Table 1.

| Indices and Groups | N | Mean ± SD | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 0.34 | ||

| Without NSLBP | 15 | 23.47 ± 5.12 | |

| With NSLBP | 15 | 21.87 ± 3.83 | |

| Height (cm) | 0.10 | ||

| Without NSLBP | 15 | 189.13 ± 9.94 | |

| With NSLBP | 15 | 183.33 ± 9.01 | |

| Weight (kg) | 0.27 | ||

| Without NSLBP | 15 | 80.60 ± 11.31 | |

| With NSLBP | 15 | 76.33 ± 9.49 | |

| BMI | 0.81 | ||

| Without NSLBP | 15 | 22.48 ± 2.31 | |

| With NSLBP | 15 | 1.77 ± 22.66 |

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; NSLBP, non-specific low back pain.

3.2. Apparatus and Task

3.2.1. Slump Test

This test was used as a sensitive physical examination tool in patients with symptoms of NSLBP. The participants were positioned in long sitting, feet against a hand of examiner to maintain neutral dorsiflexion angle, trunk flexed to enhance dural elongation, while the examiner applied cervical overpressure to ensure a sustained pressure just at the onset of symptom onset (18, 19).

3.2.2. Straight Leg Rising Test

In straight leg rising (SLR) test that was used to detect neural symptoms from those of musculoskeletal origin, subjects lies supine on the examination table and the examiner passively lifts the subject’s leg with fully extended knee, hip in neutral rotational position and ankle hanging free. The leg raise was continued until the first symptoms were started or the subject’s reporting symptoms in the lower extremity (18, 19).

3.2.3. Ankle Joint Position Sense

The error of actively reproduction the ankle joint angle on the dominant leg was evaluated using an isokinetic dynamometer model pro 4 (Figure 1) at two target angles of 10 and 20 degrees in the inversion movement in three attempts for each angle. The average error for each angle was recorded as an absolute error (20-24).

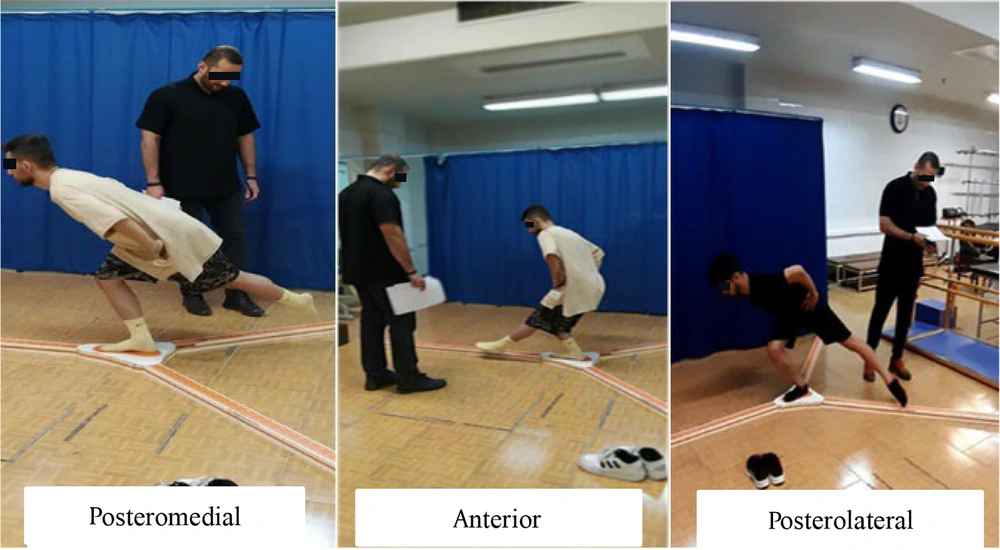

3.2.4. Y-Balance Test

A Y-balance test (YBT) kit is used to assess dynamic balance (Figure 2). After familiarizing the subjects and conducting a trial to familiarize themselves and reduce possible errors, the dynamic balance was evaluated in three anterior, posteromedial, and posterolateral directions in three attempts for each direction. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committees of Faculty of Physical Education and Sports Sciences, University of Tehran (IR.UT.SPORT.REC.1402.019). For statistical analysis, after normalizing the data according to the length of each subject’s lower limb, the highest reach distance in each direction was recorded for analysis (5, 18, 25-27). After assessing the normality of data distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test, an independent t-test was conducted to analyze differences between the variables of interest in the two groups. SPSS version 27 was used for statistical analysis, with a significance level set at α ≥ 0.05.

4. Results

Both groups were homogenous in terms of Body Mass Index (BMI), age, and gender. Demographic information is shown in Table 2. According to Table 2, the independent t-test results showed no significant difference between ankle proprioception at 10 and 20 degrees of inversion between the two groups. Regarding dynamic balance (Table 2), the results of the independent t-test showed a significant difference between the two groups in the posterior-internal (P = 0.02), posterior-external (P = 0.03) direction, and total dynamic balance score (P 0.02).

| Variables and Groups | Mean ± SD | df | t | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ankle JPS (10 degree) | 28 | -0.51 | 0.61 | |

| Without NCLBP | 1.54 ± 0.96 | |||

| With NCLBP | 1.76 ± 1.36 | |||

| Ankle JPS (20 degree) | 28 | -0.71 | 0.09 | |

| Without NCLBP | 2.68 ± 2.10 | |||

| With NCLBP | 4.14 ± 2.47 | |||

| YBT-A (%LL) a | 28 | 1.41 | 0.16 | |

| Without NCLBP | 68.16 ± 5.13 | |||

| With NCLBP | 65.27 ± 6.02 | |||

| YBT-PM | 28 | 2.45 | 0.02 a | |

| Without NCLBP | 77.86 ± 3.98 | |||

| With NCLBP | 73.34 ± 5.92 | |||

| YBT-PL | 28 | 2.19 | 0.03 a | |

| Without NCLBP | 81.45 ± 2.98 | |||

| With NCLBP | 76.80 ± 7.64 | |||

| YBT-CS | 28 | 2.40 | 0.02 a | |

| Without NCLBP | 75.82 ± 3.20 | |||

| With NCLBP | 71.80 ± 5.60 |

Abbreviations: JPS, joint position sense; YBT, Y-balance test; NSLBP, non-specific low back pain.

a Siginificant.

5. Discussion

This study compared dynamic balance and ankle proprioception between athletes with and without NSLBP. A total of 30 athletes were assigned to two groups: Fifteen with NSLBP and 15 without the condition. Both groups were homogeneous in age, height, weight, and BMI. The slump test and straight leg raising test were used to confirm the presence of LBP.

An isokinetic dynamometer was also used to determine ankle proprioception at 10 and 20 degrees of inversion. Dynamic balance was assessed using the YBT. A comparison of proprioception and dynamic balance between athletes with and without back pain revealed no significant difference in ankle proprioception at 10-degree and 20-degree inversion angles. Although the proprioceptive mean joint repositioning error was higher in group with NSLBP.

A significant difference in dynamic balance was observed between the two groups, athletes without NSLBP demonstrating significantly better dynamic balance than those with chronic NSLBP.

The results of the study on proprioception are consistent with the results of Xiao et al. (6), who indicated no relationship between the severity of chronic NSLBP and ankle proprioception in community-dwelling older adults. In line with this study, the present study showed no difference between ankle proprioception in the two groups with and without chronic nonspecific lower back pain. In contrast to the present study, findings by Claeys et al. (4), and Brumagni et al. (28) indicated differences in ankle proprioception between individuals with and without back pain. This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in proprioception assessment methods. In the current study, ankle proprioception was evaluated under non-weight-bearing conditions, whereas in the other two studies, it was assessed under weight-bearing conditions. In this context, Stillman and McMeeken (29) examined the role of weight-bearing in the clinical assessment of knee JPS. They showed that position sense in the weight-bearing condition was significantly more accurate and reliable after five tests at approximately 45 degrees of knee flexion in each test condition (lying supine and weight-bearing). They stated that during weight-bearing, subjects can better identify test positions using cues obtained while moving the knee toward the position. Also, more proprioceptive afferent information may be obtained from sources outside the examined joint and the limb used. However, in general, athletes may have been able to prevent the effect of LBP on ankle proprioception by improving muscle strength and endurance, or by performing repeated exercises, they may have been able to help improve their performance and prevent performance decline by changing strategies and brain plasticity (30). Moreover, our findings showed a different dynamic balance between athletes with and without chronic NSLBP. The present study’s findings align with those of Thakkar and Kumar, who reported a significant difference in balance between individuals with and without back pain (31). Similarly, Jafari et al. identified a negative relationship between dynamic balance and back pain in both men and women (32), further supporting the present study’s results on the impact of back pain on balance.

The lumbar muscles play a critical role in spinal stabilization (33), and weakness or pain in these muscles, along with altered lumbopelvic positioning, may influence the use of thigh strategies for balance control (34) ultimately affecting trunk, thigh, and ankle muscle strength (35). Scientific evidence indicates that muscle endurance is lower in individuals with LBP than those without the condition (36), and improving muscle endurance may help reduce back pain and prevent its occurrence. Also, muscle strength and endurance weakness lead to premature fatigue in activities that can increase the likelihood of injury to the lumbar region. Fatigue leads to loss of control, precision, and fluidity in movement, potentially as a predisposing factor for the onset or progression of LBP (37). In this regard, Amiri et al. compared pelvic floor muscle strength and endurance between individuals with chronic LBP and healthy controls, reporting a significant difference between the two groups. Among the most critical stabilizing muscles that should be strengthened to reduce or manage back pain are the transverse abdominis, internal oblique, multifidus, and quadratus lumborum (38).

Balance impairment in individuals with LBP may result from altered proprioceptive feedback from the lumbar spine (39), as proprioceptive dysfunction creates uncertainty in the sensory inputs required to maintain balance in static and dynamic conditions (40). These neuromuscular alterations may also impact functional tests such as endurance and balance assessments. Another contributing factor to reduced performance in individuals with LBP may be avoidance behavior, which further exacerbates dysfunction (41). Chronic LBP increases postural sway in a relaxed state due to diminished function and coordination of stabilizing back muscles (41). Additionally, proprioceptive transmission changes, para-spinal muscle spindle dysfunction, and delayed muscle recruitment have been linked to poor postural control (42). Balance and postural control are interrelated concepts regulated by an integrated system of static and dynamic postural mechanisms. (43). In LBP, balance disturbances are attributed to disrupted proprioceptive feedback from the lumbar spine, which impairs the activation of postural muscle patterns from the back to the ankle. Our study has some limitation such as focusing on male, screening of musculoskeletal problems by self-reporting and lack of balance assessment by more technical tools such as Biodex test.

Overall, the findings of this study confirm that dynamic balance is reduced in athletes with LBP compared to those without the condition. This deficit may be attributed to complications such as muscle weakness and impaired proprioception, which are commonly observed in individuals with LBP. According to the results of the present study, it can be suggested that athletes with non-specific back pain should consider using exercises aimed at improving balance.