1. Background

Physical inactivity is a pressing global public health issue, causing an elevated risk of chronic diseases, disabilities, and premature mortality (1). In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) released updated guidelines on physical activity, recommending that adults engage in 150 to 300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity, 75 to 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity, or an equivalent combination of both intensities weekly, in addition to regular resistance training. Adults failing to meet these recommendations are classified as physically inactive (2).

Globally, physical inactivity ranks among the top ten risk factors for mortality, with more than a quarter of adults not achieving the recommended levels of physical activity (3, 4). In 2012, it was officially recognized as a global pandemic due to its widespread prevalence and significant health implications (5).

A sedentary lifestyle is closely linked to an elevated risk of developing chronic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, obesity, specific cancers, and mental health disorders, including depression and anxiety (5, 6). Beyond its health consequences, physical inactivity imposes a substantial economic burden, with billions of dollars lost annually due to healthcare expenditures and reduced productivity (7).

Men, in particular, face a heightened vulnerability to chronic conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers. This disparity is influenced by a complex interplay of factors, including biological differences (e.g., hormonal variations), genetic and immune system responses, behavioral tendencies (e.g., unhealthy lifestyle habits and poor dietary patterns), and psychosocial and cultural influences (e.g., lower rates of healthcare-seeking behavior and greater exposure to occupational hazards). Collectively, these factors contribute to a greater disease burden and higher mortality rates among men (8, 9).

Sedentary behaviors have become increasingly common, further exacerbating the risks associated with physical inactivity. Prolonged sedentary time is linked to adverse cardiovascular outcomes, including elevated blood pressure, unfavorable lipid profiles, and vascular dysfunction, all of which significantly increase the risk of coronary artery disease (10). Prolonged sitting, particularly in physically inactive individuals, are associated with heightened risks of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. However, adherence to the WHO-recommended levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity can substantially mitigate or eliminate these risks (11).

In addition to its cardiovascular effects, physical inactivity contributes to rising obesity rates among men. Sedentary lifestyles disrupt energy balance, leading to excessive fat accumulation, particularly in visceral fat depots. This accumulation fosters systemic inflammation, which plays a central role in the development of chronic conditions such as insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, neurodegeneration, and certain cancers (12).

In the Middle East, including Iran, the prevalence of physical inactivity considerably high. According to the most recent report, among Iranian adult men aged 18 years and older, the prevalence of insufficient physical activity in 2022 was 35.9%. If the trends observed from 2010 to 2022 continue, the projected prevalence for 2030 is expected to increase to 41.6% (95% uncertainty interval: 24.6 - 60.7%) (13).

In Tehran, a rapidly urbanizing metropolitan area, lifestyle changes have further intensified the prevalence of physical inactivity among men, increasing their vulnerability to chronic diseases. In Iran and the broader Middle East, rapid urbanization, limited access to recreational spaces, and cultural norms contribute to lower physical activity levels (14, 15).

2. Objectives

Addressing this urgent public health concern, this study aims to assess physical activity levels and estimate the status of physical inactivity before COVID-19 pandemic among adult men in Tehran.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design with a descriptive-analytical approach to assess physical activity levels among adult men in Tehran. The target population included all men aged 18 to 64 years residing in Tehran (16). According to the 2016 Iranian national population and housing census, the adult male population in Tehran was estimated at approximately 3 million (17). Participants were recruited from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds across the city. Inclusion criteria required participants to be at least 18 years old, have resided in Tehran for at least six months (18, 19), and provide informed consent.

The sample size was calculated using statistical parameters (α = 0.05,

3.2. Data Collection

The data collection methodology mirrored that of a prior study conducted on women (19), although data specific to men had not been previously analyzed or reported. To achieve the study's objectives, a pilot study was conducted in District 6 of Tehran with 50 male participants. Challenges in participation rates were revealed in the pilot study, leading to an expansion of recruitment efforts. In order to recruit, the strategy involved setting up booths at four exhibitions held at the Tehran International Exhibition Center between 2018 and 2019, where study invitations were announced.

An SMS campaign was also launched. A total of 5,000 SMS invitations were sent across Tehran’s five main regions (north, south, east, west, and center), with 1,000 messages per region. To ensure equitable distribution, 500 numbers from each of the two national mobile operators (MCI and Irancell) were selected for each region. Although the total number of invitations was documented, detailed records of positive responses, screenings, and enrollments by recruitment source (SMS or exhibition) were not systematically preserved. Consequently, while the final sample size (n = 860) was achieved through both channels.

Although the initial study design sought multistage geographic coverage, recruitment ultimately relied on voluntary participation via exhibition booths and SMS invitations. Because participants self-selected into the study, the final sample represents a non-probability (convenience/purposive) sample rather than a probability-based one.

Participants' physical activity levels and daily sitting time were assessed using the Short International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) through face-to-face interviews to ensure accuracy and reliability. Originally developed by Ainsworth et al. (2000), the IPAQ's concurrent validity was assessed by Craig et al., who reported acceptable agreement between the short and long forms. Its criterion validity, based on correlations with accelerometer data, demonstrated moderate to good agreement (21). The Persian version of the IPAQ was validated in a study involving 30 female students, yielding a high test-retest reliability with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.92 (22). Based on IPAQ results, participants were categorized into low, moderate, or high levels of physical activity (23). The IPAQ is a widely used tool for measuring physical activity levels in various studies (14, 15). The questionnaire began with questions about demographic characteristics, such as age and education level.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data were summarized using descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation. Inferential statistical analyses were conducted to explore relationships and differences between variables. Independent t-tests were used to compare physical activity levels between single and married participants. Chi-square tests, one-way ANOVA, and post-hoc Scheffe tests were employed to examine differences across age groups and educational levels. Correlations between variables were assessed using Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 27 and Microsoft Excel, with the level of statistical significance set at P ≤ 0.05.

4. Results

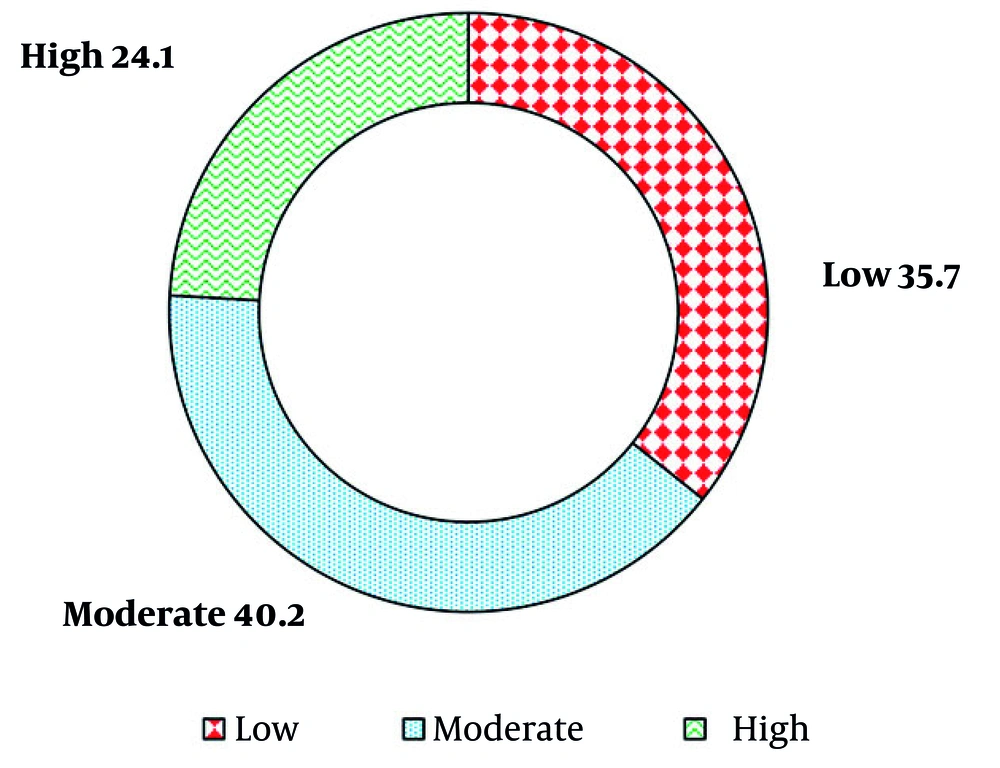

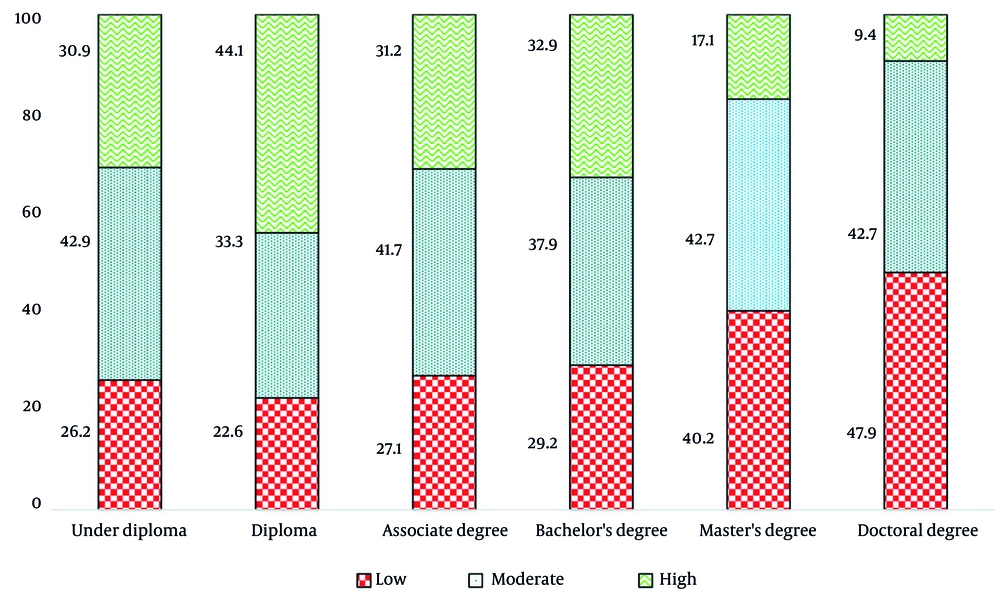

As depicted in Figure 1, the prevalence of physical inactivity among adult male residents of Tehran was 35.7%. Table 1 shows that the average energy expenditure among participants was 1600.80 MET-min/week, while the average daily sitting time was 8.07 hours. Physical inactivity increased with age up to 49 years and subsequently declined. Furthermore, the prevalence of inactivity increased with increasing levels of education (Figure 2).

| Variables | Energy Expenditure | Daily Sitting Time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean ± SD | No. | Mean ± SD | |

| Total | 860 | 1600.80 ± 1407.01 | 846 | 8.07 ± 3.51 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 377 | 1846.39 ± 1356.86 | 369 | 8.01 ± 3.43 |

| Married | 483 | 1397.20 ± 1415.60 | 472 | 8.10 ± 3.57 |

| Age groups (y) | ||||

| 20 - 29 | 311 | 2011.17 ± 1418.45 | 307 | 8.04 ± 3.44 |

| 30 - 39 | 267 | 1470.84 ± 1328.06 | 263 | 7.83 ± 3.54 |

| 40 - 49 | 159 | 1225.72 ± 1358.45 | 157 | 8.46 ± 3.61 |

| 50 - 59 | 89 | 1269.28 ± 1330.86 | 87 | 8.39 ± 3.49 |

| 60 - 64 | 34 | 1477.40 ± 1461.56 | 32 | 7.63 ± 3.42 |

| Education level | ||||

| Under diploma | 42 | 2262.93 ± 1667.43 | 41 | 5.63 ± 2.91 |

| Diploma | 84 | 2167.42 ± 1466.68 | 80 | 5.83 ± 3.49 |

| Associate | 48 | 1835.72 ± 1423.12 | 47 | 6.97 ± 3.49 |

| Bachelor | 240 | 1870.72 ± 1556.12 | 239 | 8.01 ± 3.50 |

| Master | 286 | 1376.37 ± 1250.88 | 283 | 8.50 ± 3.23 |

| Doctoral | 117 | 1049.21 ± 992.04 | 115 | 9.30 ± 3.26 |

Table 2 indicates that 29.2% of single participants and 40.8% of married participants classified as physically inactive. Also, 56.5% of participants reported sitting for more than 8 hours per day, with individuals holding higher educational qualifications more likely to fall into this category.

| Variables | Physical Activity Classification | Daily Sitting Time Classification (h) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | Vigorous | More Than 8 | 6 to 8 | 4 to Less Than 6 | Less Than 4 | |

| Total | 307 (35.7) | 346 (40.2) | 207 (24.1) | 478 (56.5) | 136 (16.1) | 139 (16.4) | 93 (11.0) |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Single | 110 (29.2) | 141 (37.4) | 126 (33.4) | 210 (56.5) | 68 (18.3) | 50 (13.4) | 44 (11.8) |

| Married | 197 (40.8) | 205 (42.4) | 81 (16.8) | 268 (56.5) | 68 (14.3) | 89 (18.8) | 49 (10.3) |

| Age groups (y) | |||||||

| 20 - 29 | 82 (26.4) | 106 (34.1) | 123 (39.5) | 170 (55.4) | 53 (17.3) | 51 (16.6) | 33 (10.7) |

| 30 - 39 | 102 (38.2) | 118 (44.2) | 47 (17.6) | 144 (54.8) | 44 (16.7) | 39 (14.8) | 36 (13.7) |

| 40 – 49 | 75 (47.2) | 66 (41.5) | 18 (11.3) | 90 (57.3) | 24 (15.3) | 34 (21.7) | 9 (5.7) |

| 50 - 59 | 37 (41.6) | 39 (43.8) | 13 (14.6) | 57 (65.5) | 9 (10.3) | 12 (13.8) | 9 (10.3) |

| 60 - 64 | 11 (32.4) | 17 (50.0) | 6 (17.6) | 17 (53.1) | 6 (18.8) | 3 (9.4) | 6 (18.8) |

| Education level | |||||||

| Under diploma | 11 (26.2) | 18 (42.9) | 13 (31.0) | 9 (22.0) | 8 (19.5) | 16 (39.0) | 8 (19.5) |

| Diploma | 19 (22.6) | 28 (33.3) | 37 (44.0) | 23 (28.7) | 14 (17.5) | 17 (21.3) | 26 (32.5) |

| Associate | 13 (27.1) | 20 (41.7) | 15 (31.3) | 22 (46.7) | 8 (17.0) | 7 (14.9) | 10 (21.3) |

| Bachelor | 70 (29.2) | 91 (37.9) | 79 (32.9) | 137 (57.3) | 33 (13.8) | 44 (18.4) | 25 (10.5) |

| Master | 115 (40.2) | 122 (42.7) | 49 (17.1) | 166 (58.7) | 59 (20.8) | 41 (14.5) | 17 (6.0) |

| Doctoral | 56 (47.9) | 50 (42.7) | 11 (9.4) | 87 (75.7) | 11 (9.6) | 12 (10.4) | 5 (4.3) |

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Table 3 presents the comparative analysis of variables among subgroups. Overall, single men reported greater energy expenditure and were less likely to be classified as physically inactive compared with married men. Physical inactivity was more common among married participants, reflecting lower engagement in active behaviors. Age differences showed that younger adults (20 - 29 years) had the highest energy expenditure, whereas activity levels declined notably among those aged 30 - 49 years. Although inactivity decreased slightly after age 50, middle-aged adults remained the most sedentary group.

| Categories | Energy Expenditure | Daily Sitting Time | Physical Activity Classification | Daily Sitting Time Classification | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t or F | P | t or F | P | t or F | P | t or F | P | |

| Marital status | 4.690 | < 0.001 | -0.390 | 0.697 | 35.055 | < 0.001 | 6.293 | 0.098 |

| Age groups (y) | 11.905 | < 0.001 | 1.106 | 0.353 | 70.236 | < 0.001 | 15.722 | 0.204 |

| Education level | 12.216 | < 0.001 | 16.397 | < 0.001 | 55.720 | < 0.001 | 103.779 | < 0.001 |

a An independent t-test was used for marital status, and a one-way ANOVA was used for comparisons among the age group and educational level categories..

Educational attainment was also closely linked to lifestyle patterns. Men with lower education levels (below diploma or diploma holders) reported higher energy expenditure and shorter daily sitting times. In contrast, participants with postgraduate degrees, particularly doctoral holders, showed the lowest levels of activity and the longest sitting durations. Education level increased, physical activity declined, and sedentary behavior became more prevalent. The correlation analysis results between the study variables are displayed in Table 4.

| Variables | Energy Expenditure | Age | Body Mass | Daily Sitting Time | Physical Activity Classification | Marital Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy expenditure | - | |||||

| Age | R = -0.208; P < 0.001 | - | ||||

| Body mass | R = -0.830; P = 0.016 | R = 0.049; P = 0.154 | - | |||

| Daily sitting time | R = -0.397; P < 0.001 | R = 0.028; P = 0.423 | R = 0.041; P = 0.235 | - | - | |

| Physical activity classification | R = 0.833; P < 0.001 | R = -0.242; P < 0.001 | R = -0.087; P = 0.012 | R = 0.356; P < 0.001 | - | |

| Marital status | R = -0.189; P < 0.001 | R = 0.680; P < 0.001 | R = 0.172; P < 0.001 | R = 0.007; P = 0.847 | R = 0.183; P < 0.001 | - |

| Education level | R = -0.236; P < 0.001 | R = -0.029; P = 0.403 | R = 0.037; P = 0.299 | R = 0.285; P < 0.001 | R = 0.234; P < 0.001 | R = -0.059; P = 0.093 |

5. Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate physical activity levels and the status of physical inactivity before COVID-19 pandemic among adult men in Tehran, focusing on the relationships between variables such as marital status, age, education level, energy expenditure, daily sitting time, and body mass. The findings revealed a significant prevalence of physical inactivity, with 35.7% of participants classified as inactive, underscoring a pressing public health concern in Tehran.

The global prevalence of physical inactivity has been increasing, with the WHO reporting an increase from 23.4% in 2000 to 31.3% in 2022 (13). In Iran, the prevalence of insufficient physical activity among Iranian adult men was estimated at 35.9% in 2022 (13). Therefore, our findings are consistent with previous and recent studies conducted in Iran and other Middle Eastern countries, which have reported physical inactivity rates ranging from 20% to 40% among adult men (4, 13, 14).

Participants in this study reported an average daily sitting time of 8.07 ± 3.51 hours, reflecting a sedentary lifestyle. This trend is likely influenced by technological advancements, mechanized lifestyles, and shifts in daily routines. Prolonged sedentary behavior, including excessive sitting and screen time, has been linked to an increased risk of all-cause mortality (24). Physiologically, extended periods of sitting impair peripheral blood flow, vascular function, and blood glucose regulation, contributing to preventable conditions such as cardiovascular disease, stroke, and diabetes (25, 26).

Marital status emerged as a significant determinant of physical inactivity, with married men displaying higher rates of inactivity than their single counterparts (40.8% vs. 29.2%). This disparity may stem from lifestyle changes associated with marriage, including increased familial responsibilities and reduced leisure time. Prior studies have similarly shown that single individuals often exhibit higher activity levels due to fewer time constraints and greater social support for recreational activities (27, 28).

Age-related trends in physical inactivity followed a U-shaped curve, peaking in the 40 - 49 age group before declining in older adults. This pattern may reflect midlife constraints, such as occupational and familial responsibilities, which limit opportunities for physical activity. Conversely, the observed decrease in inactivity among older adults could result from increased health awareness or engagement in light physical activities post-retirement. However, caution is warranted when interpreting this trend, as other research has reported higher sedentary behavior in older populations due to reduced physical capacity and motivation (29). Encouraging light activities, such as walking or gentle exercises, among older adults can mitigate health risks and promote well-being.

Educational attainment was positively associated with both physical inactivity and sedentary behavior. Participants with doctoral degrees exhibited the highest inactivity rates (47.9%) and reported longer sitting durations, often exceeding eight hours daily. These findings align with evidence that professional occupations requiring advanced qualifications tend to be more sedentary (30). This underscores the need for workplace interventions to promote physical activity, particularly among highly educated individuals.

Beyond individual characteristics, specific cultural and environmental factors in Tehran play a crucial role in shaping physical activity behaviors. As a rapidly urbanizing metropolis, Tehran faces challenges such as heavy traffic congestion, prolonged commuting times, and a lack of pedestrian-friendly infrastructure, all of which limit opportunities for active commuting and outdoor exercise. Moreover, restricted access to safe and affordable sports facilities, compounded by air pollution and other environmental stressors, further discourage engagement in outdoor physical activity. Cultural and occupational factors, including long working hours and predominantly sedentary office-based jobs, also contribute to excessive daily sitting times. Collectively, these environmental, cultural, and occupational barriers help explain the high prevalence of sedentary lifestyles observed in this study.

Based on the findings of this study and in alignment with WHO’s Global Action Plan on physical activity, several multi-level interventions are recommended to address the high prevalence of physical inactivity among adult men in Tehran. Urban-level interventions should prioritize active infrastructure development, including pedestrian corridors and bicycle lanes in under-served areas. Workplace wellness initiatives such as active breaks and ergonomic redesigns can mitigate sedentary time among professionals. At the community level, expanding affordable recreational opportunities and subsidized municipal sports facilities can promote equitable access. Policy frameworks that provide fiscal incentives for active mobility planning, alongside culturally sensitive health campaigns emphasizing feasible activity patterns and family-based participation, are also warranted. Together, these approaches can create a supportive ecosystem for reducing sedentary behaviors and fostering active lifestyles among Tehran’s adult male population.

The cross-sectional design of this pre-COVID-19 study and the use of a non-probability (convenience/purposive) sampling approach limit the generalizability of the findings, as participants self-selected into the study and may not fully represent Tehran’s broader adult male population. Moreover, since the study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, subsequent changes in physical activity behaviors may have altered the relevance of certain patterns observed. The reliance on self-reported measures introduces potential recall and social desirability biases, which may affect the accuracy of physical activity estimates. Future research should employ objective measurement tools, such as accelerometers, to validate self-reported data and conduct longitudinal studies to establish causal relationships between demographic factors and physical activity behaviors, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the determinants of inactivity in this population.

The study highlights the high prevalence of physical inactivity before COVID-19 pandemic among adult men in Tehran, emphasizing the urgent need for preventive strategies and interventions. Given the established association between physical inactivity and chronic diseases, policymakers should strengthen programs and policies aimed at promoting physical activity. Addressing this public health challenge requires tailored approaches targeting specific demographic groups to mitigate the adverse effects of inactivity and foster healthier lifestyles.