1. Background

Physical literacy is a multidimensional concept encompassing motivation, confidence, physical competence, knowledge, and understanding required to engage in physical activity throughout life (1). Individuals with higher levels of physical literacy are more likely to maintain an active lifestyle across their lifespan (2). Despite the increasing recognition of its importance, there is still considerable debate over how to effectively assess physical literacy, given its complex and holistic nature (3). Selecting appropriate assessment tools requires careful consideration of their psychometric properties within specific cultural and contextual frameworks, such as schools or community-based programs.

Reliable and valid instruments are essential for assessing physical literacy across diverse populations. One of the most comprehensive toolsets for this purpose is the physical literacy assessment for youth (PLAY), which evaluates multiple perspectives, including the child, parent, and coach (4). Developed by sport for life in Canada, PLAY provides a broad evaluation of children’s physical literacy across various domains. The multidimensional and comprehensive concept of physical literacy underlying PLAY was primarily developed by Margaret whitehead. The PLAY suite consists of several tools: PLAYfun (self-assessed by the child), PLAYcoach (completed by coaches or physical educators), and PLAYparent, which captures the parent's perspective on their child’s physical literacy.

Parents are crucial in shaping children’s physical activity and literacy development (5). PLAYparent helps parents assess their child’s abilities and identify potential gaps (6). Its primary goal is to evaluate children’s physical literacy based on parental observations in everyday, home-based contexts. The tool covers four subscales: Cognitive domain (knowledge and understanding), motor competence (locomotor and stability skills), object control (e.g., throwing, catching, kicking), and environment (confidence and motivation in various physical activity settings). This framework enables a multidimensional and ecologically valid understanding of children’s physical literacy development (2, 7, 8). Widely used in English-speaking countries, PLAY tools have proven effective in capturing the complex nature of physical literacy (8).

In recent years, efforts to adapt physical literacy tools for non-English-speaking contexts — especially in the Middle East — have increased. This ensures tools retain their conceptual integrity and psychometric validity in new cultural contexts. In Iran, tools like the perceived physical literacy instrument (PPLI) (9), the Canadian Physical Literacy Knowledge Questionnaire (PLKQ-2) (10), the Adolescent Physical Literacy Questionnaire (APLQ) (11), and the Canadian Assessment of Physical Literacy (CAPL) (12) have shown acceptable validity and reliability. However, tools like CAPL often require trained administrators, specific equipment, and structured testing environments, making them time-consuming and resource-intensive, which can limit their feasibility for large-scale or community-based assessments. Similarly, the PPLI, while comprehensive, may be less accessible to parents due to its complexity and focus on educator-based evaluation. While tools such as CAPL and PPLI have been validated in Persian, they are not designed to capture parental observations. Canadian Assessment of Physical Literacy requires formal testing by trained personnel, and PPLI targets youth self-perception. Therefore, these tools overlook the nuanced and ecologically valid insights that parents can provide, highlighting the gap that PLAYparent seeks to fill. The PLAYparent tool offers a practical, parent-friendly, and cost-effective alternative that enables early identification of physical literacy levels from a familial perspective, promoting broader engagement and longitudinal monitoring within everyday environments.

While educators and coaches play a pivotal role in fostering physical literacy among children (13), parental influence is equally critical. Research has shown that parents not only shape their children’s early physical experiences but also hold strong beliefs about their responsibilities in this domain. In one study, 87.7% of surveyed parents stated that they considered themselves primarily responsible for supporting the development of their child’s physical literacy (14). Therefore, including the parental perspective in the assessment process provides a more comprehensive understanding of the child’s physical literacy profile.

Iranian culture, parents play a central role in shaping children’s educational and behavioral development. Given the limited school-based physical education infrastructure and strong parental involvement, assessing physical literacy from the parent's perspective provides meaningful insights into children’s daily activity patterns and support systems. This cultural context underscores the need for a parent-report tool tailored to Iran.

Although tools such as CAPL and PPLI have been validated in Persian, they do not capture the home-based, parental perspective. Canadian Assessment of Physical Literacy requires formal assessment by trained personnel, and PPLI targets youth self-perception, making them less feasible for family-centered evaluations. Among the PLAY tools, PLAYparent uniquely reflects parents’ views on their child’s motivation, competence, and participation in physical activity.

However, the PLAYparent tool has not yet been validated in the Iranian context. There is a clear lack of culturally and linguistically appropriate tools to assess physical literacy from a parental perspective in Iran. This study addresses that gap by evaluating the psychometric properties of the Persian version of PLAYparent. When used alongside other PLAY tools, it offers a cost-effective and ecologically valid approach to establishing a baseline understanding of children's physical literacy within the family environment (15).

2. Objectives

Therefore, the present study aimed to translate, culturally adapt, and examine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the PLAYparent tool. This validation is a critical step toward providing Iranian researchers, educators, and policymakers with a reliable and culturally appropriate instrument for evaluating physical literacy in youth from the perspective of parents.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

Participants were recruited from parents of healthy male and female children aged 8 to 12 years who were enrolled in grades two through six at conveniently selected elementary schools in Tehran Province, Iran. All schools were located in both urban and rural areas of Tehran province and included both public and private institutions. This mix contributes to the generalizability of the findings across different educational settings. Schools were selected from areas with an average socio-economic status (based on the housing prices in the area), which served as an inclusion criterion. Participation was voluntary, and all parents completed the Persian version of the PLAYparent questionnaire. In total, 212 fully completed questionnaires were collected. This sample size is consistent with Boomsma’s recommendation of a minimum of 100 participants for factor analysis, as well as Bentler and Chou’s guideline of 5 to 10 participants per estimated parameter, as referenced by Whittaker and Schumacker (16) and Kline (17), who suggest 10 to 20 participants per variable.

3.2. Apparatus and Task

3.2.1. Demographic Questionnaire

A demographic questionnaire was used to collect background information about the participants.

3.2.2. PLAYparent Questionnaire

The PLAYparent is a 19-item parent-report instrument designed to assess a child's physical literacy across four domains (7):

1. Cognitive domain – including motivation, confidence, and understanding the importance of physical activity.

2. Motor competence – focusing on locomotor and stability skills.

3. Object control – assessing manipulative skills using both hands and feet.

4. Environment – measuring engagement and confidence in various physical activity contexts.

Items are rated on a 3-point Likert scale (0 = low, 1 = moderate, 2 = high). Each subscale has a distinct scoring system with specific cut-off ranges to classify performance levels:

- Cognitive and motor competence subscales

(1) 8 - 12: Desirable performance

(2) 4 - 7: Moderate performance

(3) 0 - 3: Low performance

- Object control subscale

(1) 5 - 6: High competence

(2) 3 - 4: Moderate competence

(3) 0 - 2: Low competence

- Environment subscale

(1) 6 - 8: High confidence and engagement

(2) 3 - 5: Moderate experience

(3) 0 - 2: Limited experience

Due to differences in scoring systems, direct comparison between subscales is not recommended. Instead, each subscale should be interpreted independently to guide more precise and targeted interventions.

3.3. Procedure

The psychometric evaluation of the Persian PLAYparent questionnaire followed the standardized procedures proposed by Cruchinho et al. (18). Emphasizing systematic translation, cultural adaptation, and validation. This framework includes assessing construct and content validity, as well as measurement invariance, with a recommended sample size of at least 10 participants per item to ensure statistical rigor.

Initially, the questionnaire was translated into Persian by a bilingual expert, followed by independent back-translation into English. The back-translated version was compared with the original to ensure conceptual and semantic equivalence. A panel of three bilingual experts in physical literacy and psychometrics then reviewed the draft to confirm cultural relevance and clarity.

The final version was distributed online to parents of school-aged children who had provided informed consent. A standardized definition of physical literacy was presented to ensure shared understanding, and parents were instructed to complete the questionnaire based on their child’s current physical literacy level. Clear guidance was provided for completing the survey. Confidentiality was assured, and parents were encouraged to answer honestly to support the study's validity. This comprehensive process ensured that the adapted questionnaire maintained its conceptual integrity and cultural relevance within the Iranian context.

3.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (central tendency and variability) summarized the data. Internal consistency was assessed via composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), and Cronbach’s alpha (≥ 0.70 acceptable). Construct validity was examined through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using structural equation modeling (SEM). A second-order CFA evaluated the original factor structure’s fit in the Persian context. Model fit was assessed using the normed chi-square (χ²/df), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). In addition, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess internal consistency, with values above 0.70 considered acceptable (19). Analyses were conducted in SPSS (v27) and AMOS (v24).

4. Results

4.1. Item Analysis

To evaluate the precision and contribution of each item to the overall construct, item analysis was conducted using the discrimination index and the loop method. The discrimination index, calculated as the correlation between each item and the total score, indicates whether an item effectively differentiates between individuals with high and low levels of the measured trait. The results showed that all items — except for item 4 of the cognitive subscale — had statistically significant correlations with the total score.

These findings suggest that the items generally demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency and were retained for subsequent analyses. However, item retention should not rely solely on the discrimination index. According to the loop method, if Cronbach’s alpha decreases upon deletion of an item, it implies that the item positively contributes to internal consistency. The analysis revealed that removing any item — except for item 4 of the cognitive subscale — led to a decrease in reliability, confirming that all remaining items demonstrated acceptable homogeneity.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

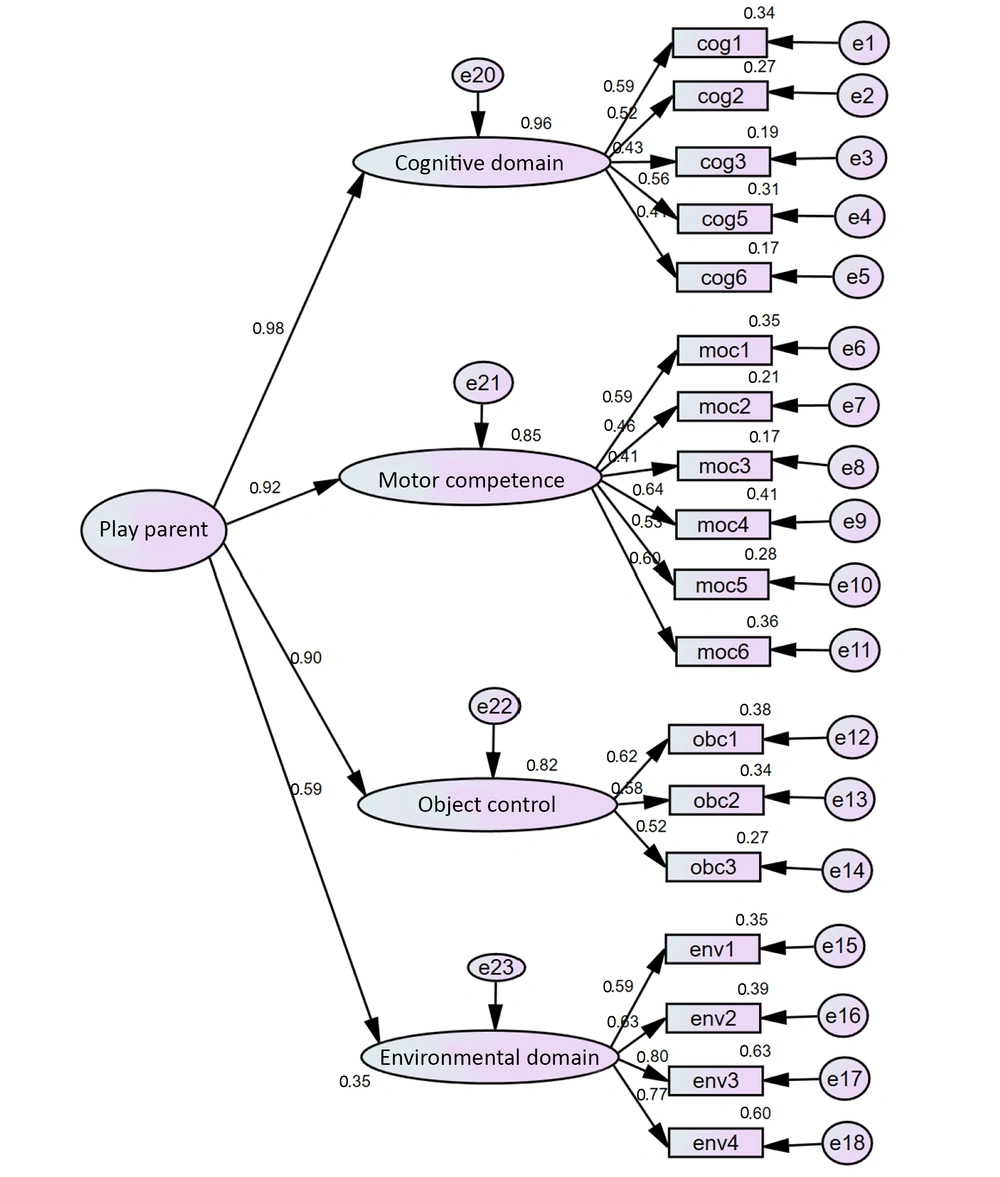

Construct validity was assessed using CFA, which is appropriate when a theoretical model is specified a priori. Item 4 of the cognitive subscale was excluded from further analysis due to poor internal consistency and a low factor loading of 0.10 (below the acceptable threshold of 0.30). A second-order CFA was then performed based on a four-factor model consisting of 18 items (excluding item Cog4) (Figure 1).

As shown in Table 1, standardized estimates using maximum likelihood (ML) indicated that all regression weights were significantly different from zero. Each item showed a significant loading on its corresponding latent factor, supporting the reliability of items in measuring their intended constructs.

| Observed and Latent Variables Relationship | Standard Estimate a |

|---|---|

| PLAYparent-cognitive domain factor | 0.98 |

| PLAYparent-motor competence factor | 0.92 |

| PLAYparent-object control factor | 0.90 |

| PLAYparent-environment domain factor | 0.59 |

| Cognitive domain factor-item cog1 | 0.59 |

| Cognitive domain factor-item cog2 | 0.52 |

| Cognitive domain factor-item cog3 | 0.43 |

| Cognitive domain factor-item cog5 | 0.56 |

| Cognitive domain factor-item cog6 | 0.41 |

| Motor competence factor-item moc1 | 0.59 |

| Motor competence factor-item moc2 | 0.46 |

| Motor competence factor-item moc3 | 0.41 |

| Motor competence factor-item moc4 | 0.64 |

| Motor competence factor-item moc5 | 0.53 |

| Motor competence factor-item moc6 | 0.60 |

| Object control factor-item obc1 | 0.62 |

| Object control factor-item obc2 | 0.56 |

| Object control factor-item obc3 | 0.52 |

| Environment domain factor-item env1 | 0.59 |

| Environment domain factor-item env2 | 0.63 |

| Environment domain factor-item env3 | 0.80 |

| Environment domain factor-item env4 | 0.77 |

Abbreviations: Cog, cognitive domain; moc, motor competence; obc, object control; env, environmental domain.

a P < 0.01.

Factor loadings identified the most influential items in each domain: Item 1 in cognitive (0.59), item 3 in motor competence (0.64), item 1 in object control (0.62), and item 3 in environment (0.80). These items demonstrated the strongest predictive power for their respective latent variables. No path removal or model modification was required. The validity of the proposed four-factor structure and the item-subscale assignments was further examined through a second-order CFA. Model fit indices, calculated using AMOS software and the ML estimation method, are summarized in Table 2.

Abbreviations: CFI, Comparative Fit Index; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation.

a χ² = Chi-square.

b Normed chi-square.

A comprehensive assessment of model fit considered both global fit indices and the significance of individual parameter estimates. Accordingly, the analysis included goodness-of-fit indices (where higher values indicate better model fit) and badness-of-fit indices (where higher values indicate poorer fit). No single fit index can independently determine the adequacy of a measurement model. Instead, model evaluation should rely on a combination of fit indices, each offering distinct and complementary insights into model performance. As recommended by Kline, a robust evaluation typically includes absolute fit indices, comparative (incremental) fit indices, and parsimonious fit indices (17). In this study, the overall fit of the proposed four-factor model was assessed using several indicators: χ², χ²/df, RMSEA, CFI, and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI).

Although the χ² statistic was significant, it is important to note that this index is highly sensitive to sample size. In studies with large samples, even minor discrepancies between the model and the observed data can lead to statistically significant results (17, 20). Therefore, researchers have recommended relying on additional fit indices such as χ²/df, CFI, RMSEA, and TLI to more accurately assess model fit (21). In the present study, despite the significant χ², the other fit indices fell within acceptable ranges, indicating an overall good model fit (CFI = 0.92, TLI= 0.91, RMSEA = 0.045, χ²/df = 1.50). For the CFI and TLI, values greater than 0.90 are generally interpreted as indicative of good model fit, while values exceeding 0.95 reflect an excellent fit. RMSEA values below 0.06 suggest a well-fitting model (Xia & Yang, 2019, as cited in Hu & Bentler, 1999) (21, 22). Although there is no universally agreed-upon threshold for the normed chi-square (χ²/df), values below 3 are commonly considered desirable (17) and some scholars regard values between 2 and 5 as indicating an acceptable level of fit (23).

Considering both the individual parameter estimates and the set of model fit indices — each evaluated against established benchmark criteria — the proposed four-factor structure, designed to assess Iranian parents’ perceptions of their children’s physical literacy, demonstrates satisfactory model adequacy. Specifically:

(1) Items 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 correspond to parents’ cognitive evaluations of their children’s physical and motor development.

(2) Items 7 through 12 reflect perceived motor competence, including locomotor, stability, and balance skills.

(3) Items 13 to 15 assess perceptions of the child’s object control abilities.

(4) Items 16 to 18 pertain to environmental opportunities that facilitate the child’s engagement in physical activities.

4.3. Internal Consistency and Reliability

Although the overall Cronbach’s alpha for the 212 parents was 0.85, recent research in behavioral and social sciences has moved beyond sole reliance on this index. More robust indicators like CR and AVE are now preferred. Cronbach’s alpha assumes tau-equivalence — that all items have equal loadings on the latent construct — which is often violated, leading to over- or underestimation of reliability (24). In contrast, CR and AVE, derived from SEM, reflect actual factor loadings, offering more accurate assessments.

Composite reliability measures internal consistency by accounting for varying loadings and is considered more valid than alpha (25). Average variance extracted indicates convergent validity, showing how well a construct explains the variance of its indicators. Together, they provide a more theoretically grounded evaluation of reliability in SEM.

In this study, CR values (Equation 1) were 0.946 (total scale), 0.831 (cognitive), 0.854 (motor competencE), 0.745 (object control), and 0.798 (environment). Average variance extracted values (Equation 2) met or approached the 0.50 benchmark for all subscales, with object control slightly below (0.494) but acceptable due to its strong CR.

Note: λi = factor loading of item i; θi = error variance of item i; CR = Composite reliability; AVE = Average variance extracted.

These findings indicate that the instrument demonstrates satisfactory internal consistency and acceptable convergent validity.

The scale effectively captures four key domains: Cognitive understanding, motor competence (including locomotion and stability), object control, and environment opportunities. Finally, descriptive statistics reflecting parents’ evaluations of their children’s physical literacy are presented in Table 3.

| Scale | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| PLAYparent | 24.86 ± 7.26 |

| Cognitive domain factor | 7.87 ± 2.54 |

| Motor competence | 8.12 ± 2.82 |

| Object control | 4.06 ± 1.65 |

| Environment domain | 4.83 ± 2.09 |

5. Discussion

This study evaluated the psychometric properties — validity and reliability — of the Persian PLAYparent questionnaire. Valid, culturally adapted tools are crucial for assessing physical literacy in diverse, especially non-Western, populations (1). The translation and adaptation followed Cruchinho et al. (18), emphasizing systematic validation and confirmatory testing across cultures (26). The main goal was to verify if the original PLAYparent factor structure is valid in Iran, using CFA, CR, and AVE as robust internal consistency indicators (27).

Initial item analysis showed 18 items with satisfactory inter-item and item-total correlations, supporting internal consistency. Confirmatory factor analysis results indicated high CR values for the total scale (0.946) and subscales — cognitive (0.831), motor competence (0.854), object control (0.745), and environment (0.798) — demonstrating strong reliability. Average variance extracted values met or nearly reached the 0.50 threshold. Although the object control subscale’s AVE was slightly below 0.50 (0.494), it is acceptable given its adequate CR [> 0.70 (according to Fornell and Larcker, satisfactory CR can compensate for marginal AVE] (27), indicating acceptable internal consistency and convergent validity for this subscale (28).

The second-order factor model strongly supports the structural validity of the Persian PLAYparent questionnaire. All factor loadings were significant, confirming that each item meaningfully contributes to its higher-order latent construct (17), consistent with the multidimensional framework of physical literacy. Goodness-of-fit indices confirmed that the four-factor model fits the data well. The normed chi-square (χ²/df) was 1.50, well below the threshold of 3, indicating a good balance between model complexity and fit (16). The RMSEA was 0.045, below the cutoff of 0.06, suggesting minimal residual variance and close model fit. CFI and TLI values of 0.92 and 0.91 exceeded the 0.90 benchmark for acceptable fit (20, 21). These indices indicate that the model explains the data better than a null model. Overall, strong factor loadings and fit indices confirm the robustness of the four-factor model and support the conceptual integrity of the Persian PLAYparent, consistent with the findings of Caldwell et al. (7).

Compared to prior Persian tools like PPLI (9), this study uniquely validates a parent-report instrument capturing children’s physical literacy in everyday settings, with a multidimensional structure covering motivational, cognitive, motor, and environmental domains. This aligns with Caldwell et al.’s emphasis on preserving multidimensionality in assessments (7).

According to the questionnaire’s scoring guidelines, results indicated that children in this sample demonstrated desirable levels of motor competence, suggesting they are generally able to move efficiently and effectively through space. However, the other three subscales — object control, cognitive, and environment — were rated at average levels. This finding implies that while foundational motor skills may be relatively well-developed, further support and encouragement are necessary to foster broader engagement with physical activity. For example, while many children showed a solid base in bilateral coordination and the use of both dominant and non-dominant limbs, there remains room for improvement. Similarly, although basic hand and foot coordination was present, additional practice is needed to reach higher proficiency. These observations highlight the critical role of diverse motor experiences, along with environment and familial support, in cultivating well-rounded physical literacy (1).

These indices collectively support the psychometric soundness and cultural applicability of the four-factor structure proposed in the original English PLAYparent tool. Strong factor loadings and fit indices confirm the adequacy of the Persian version, preserving the conceptual and measurement integrity of the original. While broadly consistent with English-speaking contexts, cultural differences — such as Iranian parents' potential emphasis on academic over physical development — may influence responses. Further cross-cultural research is warranted.

Limitations include reliance on parent-reports, prone to bias from expectations and limited observation; missing demographic data on parents (gender, age, education, SES, physical activity) that could affect perceptions; geographic restriction to Tehran province; and cross-sectional design limiting causal inference. Future research should test test-retest reliability (ICC), examine concurrent validity with other tools, conduct longitudinal intervention studies, and perform cross-cultural comparisons.

In conclusion, the Persian PLAYparent demonstrates strong structural validity, reliability, and conceptual alignment with the original tool. It is culturally and psychometrically suitable for Iran and contributes to global cross-cultural physical literacy assessment. It serves educators, researchers, and policymakers in identifying at-risk children and guiding parent-focused, school, and policy interventions to foster holistic physical literacy in families and communities.