1. Background

The ability to learn is essential for all living beings, enabling adaptation and the utilization of past experiences (1). In sports, performance results from the dynamic interaction between the individual, environment, and task. While coaches have historically emphasized physical abilities, research demonstrates that athletic success depends on multiple factors, including training, instruction, innate ability, psychological skills, and motivation (2). Learning is broadly categorized into explicit and implicit types, which are functionally and neurologically distinct. Explicit learning involves the conscious acquisition of rules through demonstrations, verbal cues, feedback, and imagery (3, 4). Conversely, implicit learning occurs without conscious awareness, relying on procedural processes that minimize working memory engagement (5, 6). Another key distinction between explicit and implicit learning lies in their encoding and retrieval mechanisms, which are governed by distinct neural networks (7). Athletes trained implicitly demonstrate advantages under pressure, including reduced susceptibility to “reinvestment”, a phenomenon in which the conscious application of learned rules disrupts automated performance (8, 9). For example, football players trained implicitly exhibited superior penalty accuracy compared to explicitly trained counterparts, despite similar decision-making levels (10).

Even well-learned skills can decline after brief interruptions, a phenomenon known as warm-up decrement (WUD) (11, 12). The WUD is particularly relevant in sports where athletes complete a warm-up routine before competition or intense training (13). These routines are designed to prepare the neuromuscular system, raise muscle temperature, improve flexibility, and enhance psychological readiness (14). The benefits of warm-up can diminish over time, particularly after delays or when task demands differ, making it crucial to understand WUD mechanisms to optimize training and maintain peak performance (15). The set hypothesis suggests that optimal motor performance relies on both the skill itself and the readiness of supporting sensory, perceptual, and cognitive systems, which decline during rest, causing temporary performance drops (WUD). Implicitly learned skills, being more procedural and automated, resist WUD better by enabling quicker reactivation of these systems. In contrast, explicitly learned, rule-based skills are more vulnerable to disruption during pauses (11).

A study on billiards players found that motivational and instructional self-talk, both explicit and implicit, can help reduce WUD during rest periods (16). Another study on imagery techniques suggested that mental imagery is an effective method for minimizing WUD, especially for open motor skills, and recommended the use of external imagery for such tasks (17). Mohammadzadeh et al. (18) showed that post-rest skill recovery in volleyball serves depends on different internal mechanisms, and that pre-performance activities should match the mechanical and visual-motor demands of the target skill to reduce WUD. That study also supported imagery as a valuable strategy for mitigating WUD in volleyball service execution.

2. Objectives

Although explicit and implicit learning have been widely studied, their role in mitigating WUD remains underexplored. Most research has focused on immediate performance, while the resilience of skills to short-term interruptions, such as halftime or game pauses, is unclear. Direct comparisons of these learning strategies on WUD in objective sports tasks, such as basketball free throws, are lacking. This study aims to fill this gap by examining the effects of explicit and implicit learning on WUD in basketball free-throw performance.

3. Methods

3.1. Subjects

This applied quasi-experimental study used a pre-test-post-test design with a convenience sample of 60 female high school students (M = 16.81) from Zeynabieh High School in Ahar. Participants, selected based on G*Power analysis (f2 = 0.4, α = 0.05), had no prior basketball or free-throw experience and were not members of any sports team. While this limits generalizability, the design was suitable for an initial exploratory analysis and hypothesis generation for future research. After homogenizing participants based on age (M = 16.81 years), height (M = 163.65 cm), weight (M = 59 kg), hand length (M = 37.38 cm), and pre-test scores, they were randomly assigned to the explicit (n = 30) or implicit (n = 30) learning group.

The randomization procedure, conducted via a computer-based generator (randomizer.org), involved entering all 60 participant IDs into the software, which then generated a completely randomized list. The first 30 IDs on this list were assigned to the explicit learning group, and the remaining 30 were assigned to the implicit learning group. All participants in this study provided parental consent and personal assent. To ensure a homogeneous sample with no prior basketball experience, eligibility was limited to individuals with no history of structured basketball or free-throw training and no membership on any sports teams. Furthermore, participants were excluded from the study if they had any known motor or neurological impairments, cardiovascular issues, or diagnosed disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism, or Down syndrome.

3.2. Procedure

Before starting the study, ethical approval and necessary permits were obtained from the university and relevant authorities (IR.TABRIZU.REC.1404.046). With coordination from the school principal and physical education teachers, the researcher explained the study objectives in class and distributed a questionnaire on personal information and physical activity. After completion, eligible participants were selected to take part in the experimental phase. Each group received a distinct single-session learning intervention designed according to the theoretical distinctions between explicit and implicit learning.

3.2.1. Explicit Learning Group

Participants first viewed a 2-minute instructional video, followed by four verbal cues emphasizing key technical aspects of the basketball free throw: Knee flexion, elbow alignment, wrist release, and follow-through. The researcher confirmed participants’ understanding before practice and provided corrective feedback as needed. In this condition, instruction relied on conscious attention to movement mechanics through verbal guidance and feedback.

3.2.2. Implicit Learning Group

To induce implicit learning, an analogy-based instructional approach was applied, aiming to reduce the acquisition of explicit, rule-based knowledge. Participants watched the same 2-minute silent video as the explicit group but received no technical instructions. Instead, they were given the following analogy: "Imagine you are throwing a crumpled paper ball into a wastebasket across the room. Make your movement smooth and gentle, just like that." This analogy encouraged natural, fluid movement without reliance on conscious control. Participants then practiced for 15 minutes under this condition. The paper ball analogy, though ecologically different, promotes smooth, purposeful free-throw execution and supports implicit learning by fostering movement patterns resistant to conscious interference (19).

3.3. Warm-up Decrement Protocol

The WUD assessment protocol was conducted immediately after the learning phase. Following the learning phase, all participants performed a 15-minute block of free-throw practice. Scores from the final 10 throws of this block were recorded. Participants then underwent a 5-minute seated rest period. Immediately thereafter, they performed a 10-throw block, all of which were scored (post-rest 1). The average results of the 10 throws before and after the 5-minute rest were quantified. The steps mentioned above were then repeated once more with a 2-minute rest interval.

3.3.1. Manipulation Check

To assess the effectiveness of the intervention, immediately after the final throw, participants in the implicit learning group were interviewed with two open-ended questions: "What was your strategy for performing the throw?" and "What rules or techniques did you use for the shot?" Their responses were recorded and analyzed. Participants who provided more than two technical rules related to free-throw shooting (e.g., referring to elbow position, knee bend, follow-through) were classified as having acquired explicit knowledge, potentially contaminating the group. None of the participants met this exclusion criterion. The implicit condition used analogy learning to limit conscious rule formation. Post-task verbal reports confirmed that implicit learners could not articulate movement rules, verifying the manipulation.

3.4. Performance Assessment

Free-throw performance was evaluated using a standardized basketball free-throw test that provided a structured, quantitative measure of accuracy. Scoring was based on a 5-point scale: Five points for a basket, 3 points for hitting the hoop, 2 points for contacting both the hoop and backboard, 1 point for hitting only the backboard, and 0 points for missing both. Participants used a women’s regulation Molten size 6 basketball and shot from a standard 6-meter distance. This scoring procedure ensured objective assessment of shooting performance across all participants.

3.5. Data Analysis

The normality of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Since the results indicated deviations from normality, non-parametric statistical methods were employed for further analyses. Specifically, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to examine between-group differences, whereas the Friedman and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were applied to evaluate within-group comparisons.

4. Results

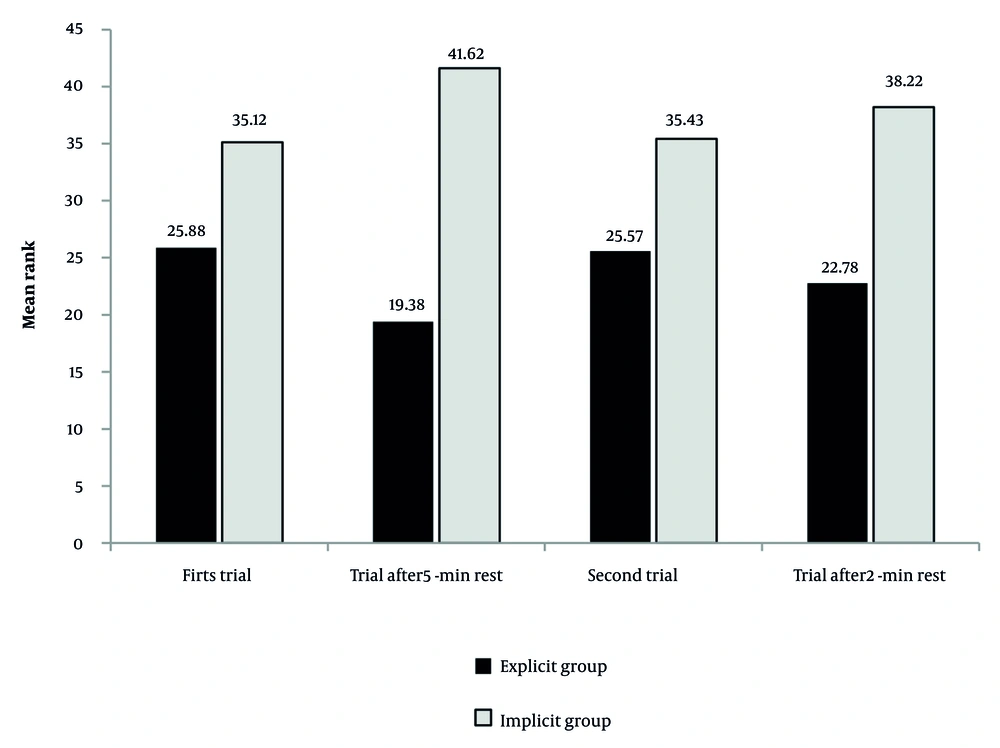

The descriptive statistics of the free-throw shooting performance are presented in Table 1.

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Mean Rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit G. | Implicit G. | Explicit G. | Implicit G. | |

| First trial | 3.39 ± 0.37 | 3.61 ± 0.37 | 25.88 | 35.12 |

| Trial after 5-min rest | 1.12 ± 0.26 | 1.61 ± 0.72 | 19.38 | 41.62 |

| Second trial | 2.86 ± 31 | 3.07 ± 0.33 | 25.57 | 35.43 |

| Trial after 2-min rest | 2.23 ± 0.38 | 2.55 ± 0.29 | 22.78 | 38.22 |

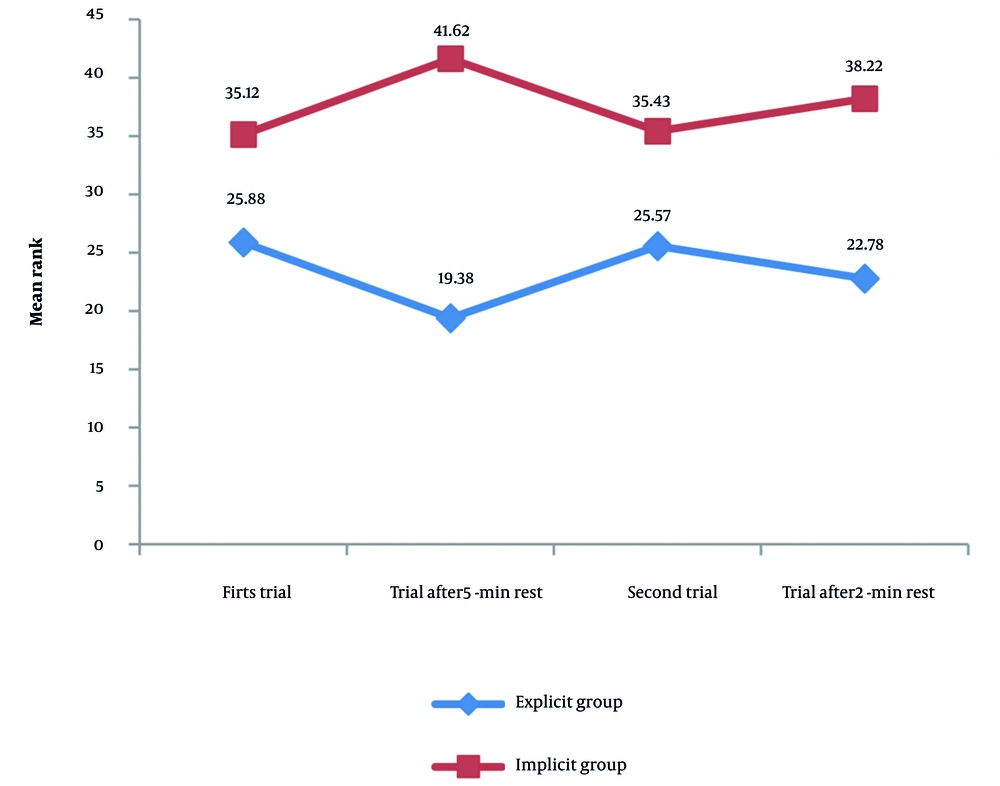

These results indicated that the implicit group performed better compared to the explicit group. Also, the mean scores of participants decreased following both five-minute and two-minute rest intervals, and the decline in free-throw performance appeared to be greater after the five-minute rest interval compared to the performance after the two-minute rest interval. To examine whether such differences are statistically significant, a Mann-Whitney U test was conducted (Table 2 and Figure 1).

| Indices | First Trial | Trial After 5-min Rest | Second Trial | Trial After 2-min Rest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mann-Whitney U | 311.50 | 116.50 | 302.00 | 218.50 |

| Wilcoxon W | 776.50 | 581.50 | 767.00 | 683.50 |

| Z | -2.26 | -5.01 | -2.44 | -3.58 |

| P-Value | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| R a | 0.29 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.46 |

a It stands for the rank-biserial correlation coefficient as the effect size measure.

As presented in Table 2 and Figure 1, there was a significant difference between the explicit group and the implicit group in terms of the first trial, the trial after a five-minute rest, the second trial, and the trial after a two-minute rest (P < 0.05), with the implicit group outperforming its counterpart. Additionally, the results of the Friedman test revealed that, depending on the condition under which the shooters threw the ball, there was a statistically significant difference in the shooting performance of the implicit group (P < 0.05). The same result was observed for the explicit group (P < 0.05). The changes in the free-throw shooting mean ranks from the first trial to the last trial are well illustrated in Figure 2.

The results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank tests (Tables 3 and 4) indicated that the implicit group showed a significant decline in shooting performance from the first trial to the trial conducted after the five-minute rest period (P < 0.05). A similar pattern was observed between the second trial and the trial following the two-minute rest period (P < 0.05), although the decline in performance appeared less pronounced after the shorter rest interval. For the explicit group, the Wilcoxon tests similarly revealed a significant decrease in shooting performance from the first trial to the trial following the five-minute rest (P < 0.05), as well as from the second trial to the trial after the two-minute rest period (P < 0.05). However, the magnitude of performance decline did not differ substantially between the two rest intervals. The Mann-Whitney U test results further demonstrated that the implicit learning group significantly outperformed the explicit learning group in both the two-minute and five-minute post-rest trials (P < 0.05).

| Groups and Indices | N | Mean Rank | Sum of Ranks | Z | P-Value | R a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implicit group | ||||||

| First trial and trial after 5-min rest | -4.61 | 0.00 | 0.59 | |||

| Negative ranks | 27 | 15.00 | 405.00 | |||

| Positive ranks | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Ties | 2 | - | - | |||

| Total | 30 | - | - | |||

| Second trial and trial after 2-min rest | -4.30 | 0.00 | 0.55 | |||

| Negative ranks | 26 | 16.92 | 440.00 | |||

| Positive ranks | 4 | 6.25 | 25.00 | |||

| Ties | 0 | - | - | |||

| Total | 30 | - | - | |||

| Explicit group | ||||||

| First trial and trial after 5-min rest | -4.78 | 0.00 | 0.61 | |||

| Negative ranks | 30 | 15.50 | 465.00 | |||

| Positive ranks | 0 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |||

| Ties | 0 | - | - | |||

| Total | 30 | - | - | |||

| Second trial and trial after 2-min rest | -4.77 | 0.00 | 0.61 | |||

| Negative ranks | 29 | 16.00 | 464.00 | |||

| Positive ranks | 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| Ties | 0 | - | - | |||

| Total | 30 | - | - |

a It stands for the rank-biserial correlation coefficient as the effect size measure.

| Variables | Percentile | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 25th | 50th | 75th | |

| Implicit group | |||

| First trial | 3.37 | 3.37 | 4.01 |

| Trial after 5-min rest | 1.20 | 1.34 | 1.53 |

| Second trial | 3.01 | 3.01 | 3.16 |

| Trial after 2-min rest | 2.25 | 2.62 | 2.62 |

| Explicit group | |||

| First trial | 3.28 | 3.37 | 3.37 |

| Trial after 5-min rest | 1.07 | 1.09 | 1.20 |

| Second trial | 2.58 | 3.01 | 3.01 |

| Trial after 2-min rest | 1.83 | 2.25 | 2.62 |

5. Discussion

The present study aimed to compare the magnitude of WUD in a basketball free-throw task following explicit and implicit learning approaches. Findings revealed a significant performance decline after rest, regardless of the learning method, confirming the occurrence of WUD (20-22). However, the implicit learning group consistently outperformed the explicit learning group across both rest intervals. Moreover, a more pronounced decline was observed following the 5-minute rest compared to the 2-minute rest, suggesting that longer interruptions may exacerbate the magnitude of WUD. It should be noted that these findings are specific to novice participants and short-term rest periods, and therefore should be interpreted cautiously when generalizing to skilled athletes or longer intervals.

According to the set hypothesis proposed by Wrisberg and Anshel, motor skill execution depends on the activation of related support systems, which may become less responsive following rest (20). The free-throw task, which requires prior planning and decision-making, may be negatively affected under certain conditions. This framework provides a theoretical basis for the superior performance of the implicit learning group in maintaining skill execution. Among the proposed explanations for WUD, such as the forgetting hypothesis, the inhibition hypothesis, and the set hypothesis, the latter currently has the strongest empirical support (23). This theory emphasizes that WUD is related to the type and timing of preparatory activity and reflects insufficient readiness to re-engage the necessary control systems for optimal performance. Supporting this notion, Silva et al. (24) reported that structured warm-up strategies and shorter rest intervals enhanced explosive performance in team sports.

Implicit learning appears to foster more stable motor execution by minimizing conscious control, thereby reducing susceptibility to errors or performance breakdowns after rest or under pressure. Conversely, explicit learning, which relies heavily on conscious monitoring and verbalized rules, may lead to “reinvestment” — the conscious control of movements that should be automatic — resulting in performance deterioration (3, 25). Previous studies have also demonstrated that implicit learners maintain higher stability under physical and mental fatigue, reflecting greater resistance to stress and cognitive disruption (8). Overall, the present findings underscore the critical role of learning approaches in mitigating WUD. Although both explicit and implicit strategies have instructional value, implicit learning appears particularly effective in preserving performance after rest (26). This approach allows motor skills to operate at a more automatic, procedural level, reducing the need for conscious reactivation and conserving cognitive and physical energy. Nonetheless, explicit learning remains beneficial for enhancing theoretical understanding and early-stage skill development, suggesting a complementary relationship between the two approaches (27).

This study’s limitations include the use of a homogeneous sample of novice female students, which restricts generalizability to other populations and genders. The ecological validity of the paper ball analogy, while theoretically grounded, may not fully replicate basketball-specific demands. Future research should investigate gender differences, include skilled athletes across diverse sports, and examine longer retention intervals and varied rest periods to enhance practical applicability. Coaches, trainers, and therapists should combine implicit learning strategies with structured warm-ups to enhance skill acquisition, performance, and resistance to WUD. Future research could examine feedback types, mental practice during rest, and gender differences.