1. Background

Parkinson's disease (PD) is one of the most prevalent neurodegenerative disorders, characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) (1). The pathological hallmarks of PD involve the accumulation and oligomerization of a highly soluble unfolded protein called alpha-synuclein within cells, which disrupts the patient’s motor activity (2). However, the main pathogenic processes leading to neuronal loss remain unclear (3). Despite extensive research, no effective treatment has been discovered to prevent or halt the neurodegenerative processes associated with PD. However, several pharmacological compounds are available to alleviate the clinical symptoms of the disease. Among these, levodopa (L-DOPA), commonly known as L-Dopa, is regarded as the gold standard for PD treatment. The L-DOPA is transported to the brain, where it is decarboxylated into dopamine, providing symptomatic relief by increasing dopamine levels in the striatum (4).

Apomorphine (APO) is a short-acting D1 and D2 receptor agonist that has demonstrated efficacy comparable to L-Dopa. However, APO acts earlier and has a shorter duration of action than L-Dopa (5). Recent studies suggest that APO is associated with an earlier onset of motor improvement and an earlier peak response compared to L-Dopa in PD patients experiencing "OFF" episodes (6). Several investigations have been conducted on the effects of L-Dopa, both alone and in combination with other chemical compounds, in animal models of PD. Recent studies have documented the therapeutic effects of L-Dopa-zinc oxide nanoparticles (7), L-Dopa combined with curcumin (8), Astragaloside IV, puerarin (9), metformin (10), OAB-14 (11), and Pelargonium graveolens (12) in PD animal models. However, most recent and previous studies have primarily focused on behavioral evaluations, with or without gene expression analysis.

2. Objectives

This comprehensive study aimed not only to compare the effects of L-Dopa and APO on behavioral and histopathological characteristics but also to evaluate the levels of alpha-synuclein and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) proteins in a rotenone-induced PD animal model. Rotenone is a neurotoxic pesticide known to disrupt oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondria (13). This disruption selectively damages dopaminergic neurons within the nigrostriatal pathway (14).

3. Methods

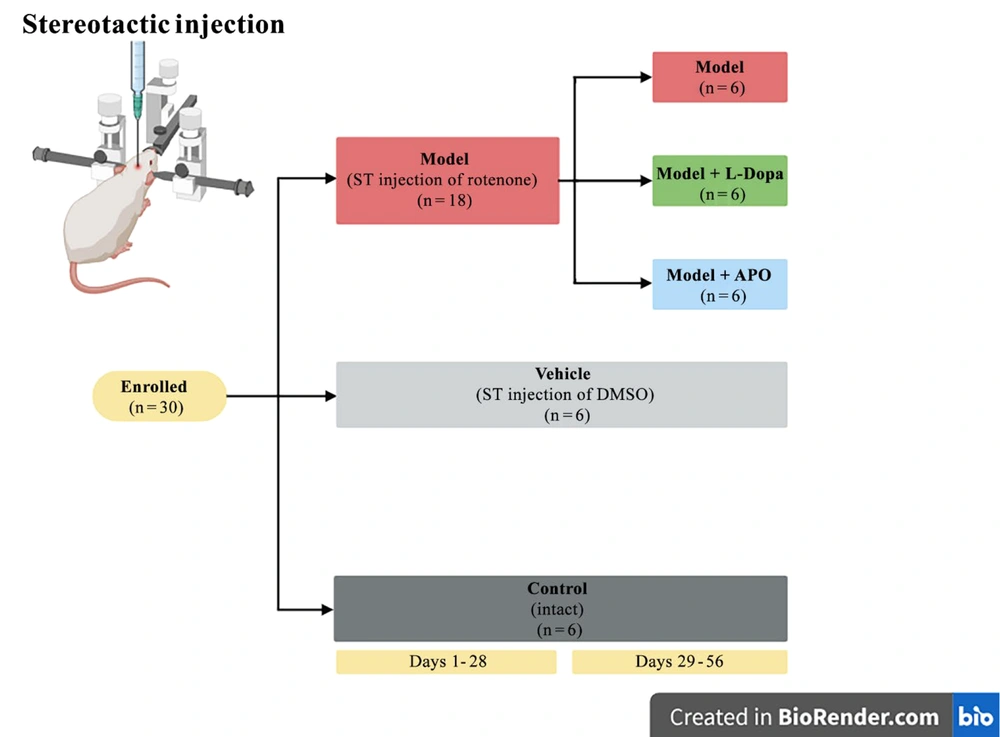

This study was conducted in accordance with the animal care guidelines and was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University (ethical No: IR.MODARES.REC.1400.177). Thirty female Wistar rats were randomly divided into five groups (n = 6): Model, model + L-Dopa, model + APO, vehicle (DMSO), and control groups (Figure 1).

On day 28 following rotenone injection, the APO group received intraperitoneal injections of 1 mg/kg APO hydrochloride for four weeks, administered on alternate days (15). In the L-Dopa group, L-Dopa/carbidopa tablets (250/25 mg) were dissolved in water, and the rats were administered 12 mg/kg of the solution via gavage twice daily for four weeks (16) (further details on the methods are provided in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File).

3.1. Behavioral Tests

To confirm the induction of the Parkinson's model, the APO-induced rotation test was performed (5). The bar test was used to evaluate catalepsy, a condition characterized by impaired movement and posture maintenance (17). Forepaw stride length measurement was done to assess motor function impairments. Muscle stiffness was analyzed by the Morpurgo test (5, 17).

3.2. Histochemical Analysis of the Brain Tissue

For histological analysis, at week 8 post-rotenone injection, the rats were sacrificed, and their brains were removed, fixed in 10% formalin, and embedded in paraffin. The paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned for immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis of alpha-synuclein and TH. Amyloid fibril deposition was studied through Congo red (CR) staining. Four microscopic images were taken from the left and right SNc areas of each rat at 40X magnification, and the mean percentage of immunoreactivity for alpha-synuclein was measured using ImageJ software. Additionally, images were captured from the aforementioned areas at 10X magnification for all groups, and the total number of TH-positive cells was counted on each side of the SNc using ImageJ software. The mild to severe amyloid formation was defined by an expert pathologist. When the amyloid formation was less than 5% of the whole section, 5 - 10%, and more than 10% at high magnification, it was defined as mild, moderate, and severe, respectively.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

Two-way ANOVA was used to analyze the data using Prism version 10 software. The analysis was followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Behavioral Findings

4.1.1. Morpurgo Findings

There was no significant difference among the groups in terms of Morpurgo findings.

4.1.2. Right Stride Length Findings

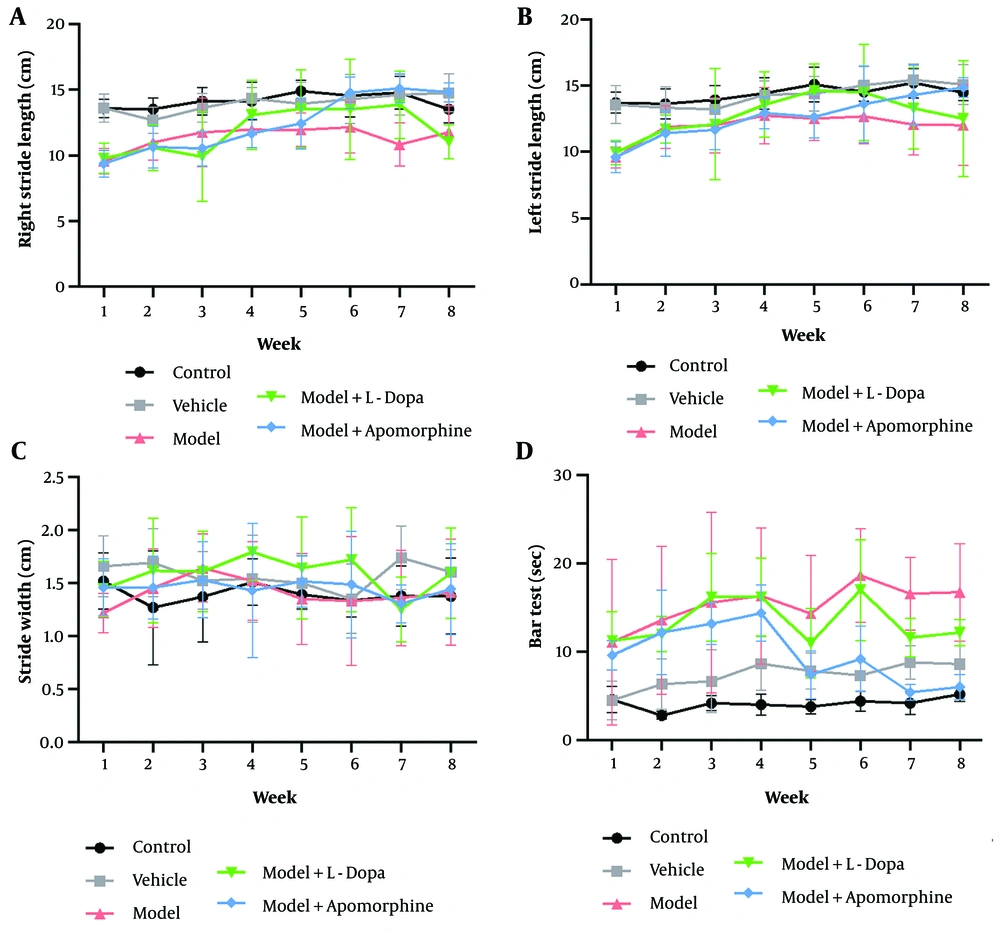

In the model, model + L-Dopa, and model + APO groups, the right stride length was significantly decreased compared to the control and vehicle groups during the first week after rotenone injection. By the third week, the right stride length in the model + L-Dopa and model + APO groups remained significantly lower than that of the control group. On the seventh week, the right stride length in the model group was significantly reduced compared to the control and vehicle groups. However, in the model + L-Dopa and model + APO groups, the right stride length showed a significant increase compared to the model group, with no significant difference observed when compared to the control and vehicle groups. By the eighth week, the right stride length in the model and model + L-Dopa groups was significantly reduced compared to the vehicle group. In contrast, the model + APO group exhibited a significant increase in right stride length compared to the model group. Notably, the right stride length in the model + L-Dopa group was significantly lower than that in the model + APO group during the eighth week (Figure 2A). The significance of the differences is presented in table 1 in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

The right stride length (A), the left stride length (B), the stride width (C), and the bar test (D) in various groups over the course of eight weeks (four weeks pretreatment and four weeks post-treatment); all significant differences between the various groups at all time points are presented in tables 1 - 3 (in Supplementary File) in the supporting information. No significant differences in stride width were observed among the groups at any time point (all data are presented as mean ± standard deviation; n = six animals in each group).

4.1.3. Left Stride Length Findings

In the model, model + L-Dopa, and model + APO groups, the left stride length was significantly decreased compared to the control and vehicle groups in the first week post-rotenone injection. The model group also showed a significantly lower left stride length than the vehicle group in the seventh and eighth weeks (Figure 2B). The significance of the differences is presented in table 2 in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File. The differences among the groups at other time points were not significant.

4.1.4. Stride Width Findings

No significant differences in stride width were observed among the groups at any time point (P > 0.05) (Figure 2C).

4.1.5. Bar Test Findings

There was no significant difference among the groups in terms of bar scores in the first week of the study. A significant increase in the bar score was found in the model groups compared to the control and vehicle groups in the second week. The bar score was significantly higher in the model + APO group than in the control groups in the second week. The bar score was also significantly higher in the model, model + APO, and model + L-Dopa groups than in the control groups in the third week. In the fourth week, the bar score of the control group was significantly lower than those of the model, model + APO, and model + L-Dopa groups. There was a significant difference between the control and model groups in terms of the bar score in the fifth week. The bar score was significantly higher in the model and model + L-Dopa groups than in the control and vehicle groups in the sixth week. Hence, the bar score was also significantly lower in the model + APO groups than in the model groups in the sixth week. In the seventh and eighth weeks, the model groups showed a higher bar score than those of the control and vehicle groups. At these times, a significant decrease in the bar score was seen in the model + APO group compared to the model group (Figure 2D). The significance of the differences is presented in table 3 in Appendix 1 in Supplementary File.

4.2. Immunohistochemistry Findings

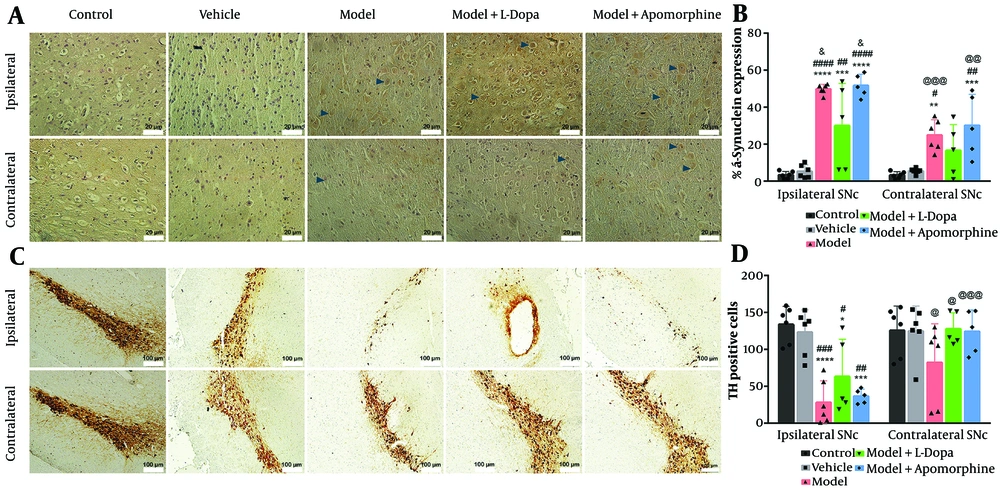

The mean percentage of alpha-synuclein expression and the total number of TH-positive cells counted by ImageJ software in the ipsilateral and contralateral SNc of different groups are shown in Figure 3B and D, respectively.

Immuno-reactivity for alpha-synuclein (A), and The mean percentage of alphasynuclein expression (B), and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) (C) in various groups within ipsilateral and contralateral areas of substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc); the brown colors (dark blue arrowhead) in A and the brown colors in C show immuno-reactivity for alpha-synuclein, and TH immunohistochemical (IHC) staining respectively. The mean TH positive cells (D) were shown in various group within ipsilateral and contralateral areas of SNc (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, and ****P < 0.0001 illustrate comparison with control group; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001, and ####P < 0.0001 illustrate comparison with vehicle group; &P < 0.05 illustrate comparison with model + levodopa (L-Dopa) group; @P < 0.05, @@P < 0.01, and @@@P < 0.001 illustrate comparison of ipsilateral SNc with contralateral SNc in each group. All data presented as mean ± standard deviation; n = six animals in each group).

The mean percentage of alpha-synuclein protein expression in both ipsilateral and contralateral SNc regions showed no significant differences between the control and vehicle groups. However, the mean expression of alpha-synuclein protein in both ipsilateral and contralateral SNc regions was significantly higher in the model and model + APO groups compared to the control and vehicle groups (P < 0.05). Although the mean expression of alpha-synuclein protein in the ipsilateral SNc of the model + L-Dopa group was significantly increased compared to the ipsilateral SNc of the control and vehicle groups (P < 0.01), the mean expression of alpha-synuclein in the contralateral SNc was not significantly different among the model + L-Dopa, control, and vehicle groups (P > 0.05). Furthermore, the mean expression of alpha-synuclein protein in the ipsilateral SNc of the model + L-Dopa group was significantly lower compared to the model and model + APO groups (P < 0.05). In addition, the mean expression of alpha-synuclein within the ipsilateral SNc of the model and model + APO groups was significantly increased compared to the contralateral SNc of the model and model + APO (P < 0.01). Hence, there was no significant difference between the ipsilateral and contralateral SNc of the model + L-Dopa in terms of the mean percentage of alpha-synuclein protein expression (Figure 3B). The microscopic images of the immune-stained tissue sections for alpha-synuclein are shown in Figure 3A.

The contralateral and ipsilateral SNc of the control and vehicle groups showed no significant difference in terms of TH-positive cells (P > 0.05). The TH-positive cells inside the contralateral SNc in all groups were not significantly different (P > 0.05); however, the TH-positive cells within the ipsilateral SNc of the model, model + L-Dopa, and model + APO groups were significantly decreased compared to the control and vehicle groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 3D). The microscopic images of the immune-stained tissue sections for TH are shown in Figure 3C.

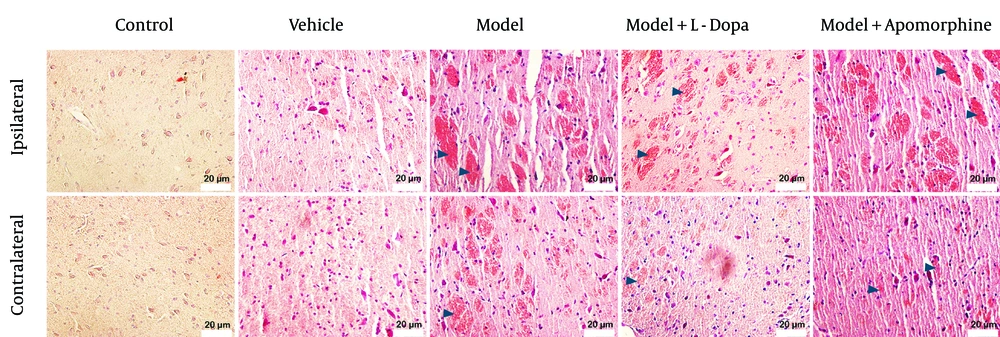

4.3. Congo Red Findings

No amyloid deposits were formed in the contralateral and ipsilateral SNc of the control and vehicle groups. A severe deposition of amyloids was observed in the ipsilateral SNc of the model and model + APO groups, as well as in the contralateral SNc of the model group. A moderate deposition of amyloids was found in the ipsilateral SNc of the model + L-Dopa group. There was mild deposition of amyloids in the contralateral SNc of the model + L-Dopa and model + APO groups (Figure 4).

5. Discussion

Among the available treatments, L-DOPA and APO administration are widely used for managing PD. This study provides a comparative analysis of the therapeutic effects of L-DOPA and APO on behavioral and histopathological changes, as well as the expression of alpha-synuclein and TH, in a rotenone-induced PD rat model. In rat models of PD, the duration of studies varies according to the specific model employed and the research objectives. Some investigations utilize 8 or 16 days after PD induction (18), while others consider 4 weeks or more after PD induction to assess the effects of pharmacological interventions (19). However, in this study, the animals were investigated for 4 weeks post-PD induction.

The absence of differences between the treatment groups (APO and L-Dopa) and the control group in terms of right stride length, a motor function indicator, during weeks five to eight post-induction suggests that both treatments effectively improved the rotenone-induced impairment in right stride length. Conversely, the left stride length remained unaffected from the second week post-induction through the treatment period. A significant increase in bar scores, indicative of catalepsy (20), was observed in all groups compared to the control group during the second week following PD induction. By the fifth week post-induction, corresponding to one week after treatment initiation, the elevated bar scores in the model and treatment groups, compared to the control group, suggest that none of the treatments effectively improved bar scores within this timeframe. However, the lower bar scores in the model + APO group compared to the model group during weeks six to eight suggest that APO administration may be a more effective strategy for addressing catalepsy in the PD model. The APO is commonly used in the management of PD to alleviate motor fluctuations and reduce “off” episodes. The APO may improve overall motor function, potentially mitigating symptoms associated with cataleptic states (21). In this study, APO treatment significantly improved performance in the bar test as a measure of cataleptic behavior, yet failed to improve stride length, a parameter of ambulatory gait patterns in rats. These findings suggest that APO could selectively improve certain motor deficits associated with PD, but not others. Considering that catalepsy predominantly arises from impaired dopaminergic signaling, the observed effects of APO as a dopamine agonist align with its expected pharmacodynamic properties. In contrast, locomotor parameters like stride length are modulated by more integrative neural pathways encompassing not only dopaminergic circuits but also cerebellar, spinal, and sensorimotor networks (22, 23). This differential response underscores the heterogeneous neurophysiological basis of motor impairments in PD.

Recent studies have demonstrated that L-Dopa effectively alleviates behavioral deficits in mice with PD symptoms (24). Although L-Dopa and APO are the two most effective therapies for PD in a rat model (7, 25), it remains unknown whether these drugs have any effect on the formation of pathogenic abnormal α-synuclein in vivo. There is a discrepancy in the reported efficacy of L-Dopa treatment in SNc-lesioned rodents overexpressing α-synuclein. While acute L-Dopa treatment has been found to possess rewarding properties in rodents overexpressing α-synuclein in rodent PD models (26), other studies indicate that L-Dopa fails to condition a rat model of PD (27). It has been recently shown that L-DOPA regulates α-synuclein accumulation in a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine non-human primate model of PD (28). Conversely, APO has been shown to inhibit α-synuclein fibrillation, leading to the formation of large oligomeric species in primary cell cultures (29). In this study, the administration of L-Dopa and APO did not alleviate the overexpression of α-synuclein induced by rotenone in the ipsilateral and contralateral regions of the SNc in the rat PD model.

Loss of TH in rotenone-induced rat models of PD has been widely documented (30, 31). Rotenone has been well established to reduce TH-positive neurons and dopamine receptor-expressing neurons throughout the central nervous system (CNS) (32). Interestingly, drugs that inhibit TH have demonstrated protective effects against neurodegeneration in various animal models of PD (33). In this study, similar immunoreactivity for TH was observed in the contralateral SNc across all groups. However, in the ipsilateral SNc, a significant reduction in TH-positive cells was observed in the model, model + L-Dopa, and model + APO groups compared to the control group, indicating that neither treatment was able to restore the decreased TH-positive cell population in the PD model.

This result contrasts with the findings of a previous study reporting elevated TH levels in the striatum and substantia nigra following L-DOPA treatment in a mouse model of PD (24). In that study, PD was induced by administering 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine at a dose of 25 mg/kg/day directly into the substantia nigra and striatum, followed by L-DOPA treatment at 8 mg/kg/day. The discrepancy between the findings may be attributed to differences in PD induction methods, L-DOPA dosing regimens, and the duration of the experimental protocols.

Amyloid-like deposits have been observed in the brains of rat models of PD induced by rotenone injection. It has been shown that rotenone exposure can lead to amyloidogenic changes, including the formation of amyloid fibrils and protein aggregates in regions like the SNc (34, 35). The severe amyloid deposition observed in the ipsilateral SNc of the model and model + APO groups, along with the moderate deposition of amyloid in the ipsilateral SNc of the model + L-Dopa group, suggests that L-Dopa is more effective than APO in reducing amyloid formation in the ipsilateral region of the PD model. Furthermore, the severe beta-amyloid formation in the contralateral SNc of the model group, compared to the mild amyloid deposition in the contralateral SNc of the model + L-Dopa and model + APO groups, indicates that both treatment approaches can reduce amyloid deposition.

Amyloid reduction may occur without changes in the levels of TH and alpha-synuclein due to a few potential mechanisms. One possibility is that the reduction in amyloid is due to the removal or destabilization of pre-existing oligomers or seeds, which are the initial nucleation sites for amyloid fibril formation, rather than a change in the overall levels of alpha-synuclein (36). Moreover, other factors like changes in the conformation or modification of alpha-synuclein, or altered amyloid fibril formation kinetics, could lead to a decrease in amyloid deposition without affecting the total amount of alpha-synuclein (37). In addition, increased oxidative stress has been shown to accelerate the aggregation of alpha-synuclein into amyloid fibrils (38). However, further investigation is needed to unravel the exact mechanism of the reduction of amyloid deposition by the administration of L-Dopa/APO in the developed PD model.

In summary, while L-DOPA and APO are among the most effective drugs for the symptomatic treatment of PD in humans, in this study, their administration led to only partial improvement in the behavioral abnormalities and some levels of reduction in amyloid deposition in the contralateral SNc region. The differences in drug effects between humans and animal models arise from a complex interplay of biological, physiological, and methodological factors. Notably, absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiles can vary significantly across species (39). For example, a drug may be rapidly metabolized in rodents but exhibit prolonged retention in humans. Additionally, differences in receptor binding affinities and downstream signaling pathways may influence both drug efficacy and toxicity (40). Another critical factor is the method of animal model development. In this case, the model was chemically induced, which fails to fully replicate the multifactorial and progressive nature of human pathophysiology.

5.1. Conclusions

Although APO and L-Dopa are among the most conventional treatments for PD, they could only improve some behavioral changes of PD in the rotenone-induced rat model of PD. Both treatment approaches could reduce amyloid deposition in the contralateral SNc of the PD model without affecting the alpha-synuclein and TH levels. These findings underscore a key translational gap, highlighting the limitations of animal models in drug development. Although animal models have played a pivotal role in drug development for decades, they may fail to reliably predict clinical outcomes in humans. The limitations of animal testing stem from a combination of interspecies biological differences and artificially controlled experimental conditions.