1. Introduction

Addressing nail diseases demands a comprehensive understanding of both specific disorders and the elements that comprise the nail unit. It is crucial to recognize how these elements interact with the biomechanics of the extremities and to take into account each patient’s unique comorbidities. This is why we will refer to the nail unit as a dynamic structure throughout the article. This holistic approach is essential for effective diagnosis and treatment. In this article, we share our viewpoint on how to manage challenging nail deformities by showcasing the case of an HIV-positive patient with nail dystrophy and aggregated onychomycosis.

2. Case Presentation

A 43-year-old female patient with a personal history of HIV infection (currently with an undetectable viral load) and multiple documented drug allergies (pregabalin, NSAIDs, egg protein, and etoricoxib) visited the nail clinic due to changes in her nails that began four years before, after experiencing trauma to her right hallux. Although she did not seek medical attention at that time, she noticed alterations in her nail. Two months before her visit, the trauma was repeated when her shoe collided with her toe, resulting in color changes and a portion of the nail falling off, which prompted her to seek consultation. She brought a nail culture that revealed the growth of Fusarium spp. She denied physical activity as part of her daily routine and reported daily use of comfortable shoes and denied other comorbidities.

During the physical examination, it was noted that the upper medial quadrant of the nail plate was absent, and there was a deep Beau’s line in the middle of the nail plate. Additionally, areas of onycholysis and leukonychia were observed, along with nail bed hyperkeratosis (Figure 1A and B). The diagnosis of nail dystrophy with onycholysis secondary to trauma, with a superimposed onychomycosis, was made. A step-by-step treatment approach was initiated over a four-month period, utilizing only topical treatments to avoid unnecessary drug interactions.

One session of mechanical dermabrasion was performed to remove the contaminated plate, remove hyperkeratosis from the nail bed, and stimulate adhesion of the plate (1, 2). The patient was prescribed terbinafine cream 1% to be applied every night in the area left without nail plate based on some cases in the literature that report susceptibility of Fusarium spp. to this medication (3, 4). Topical tretinoin cream 0.05% was initiated three nights a week to prevent hyperkeratosis of the bed. Every morning, an emulsion containing urea, coconut oil, lactate, and thymol was applied to improve nail unit hydration (5, 6) and as complementary antimycotic therapy (7-10). She was instructed to use kinesiology tape on the periungual folds every day during treatment and to gently trim nail bed hyperkeratosis with nail clippers two or three times a week.

The patient was monitored monthly throughout the treatment period to assess the hyperkeratosis of the nail bed, the proper positioning of the kinesiology tape, and her adherence to the treatment regimen. After four months of treatment, she experienced nearly complete resolution of her condition. At the nine-month follow-up, a complete response was achieved (Figure 1C and D).

3. Discussion

Onychomycosis is a frequent cause of chronic onycholysis that can lead to nail dystrophy; unfortunately, the cure rates are low, and the recurrence rate is high (11). Currently, there are few articles that describe the non-surgical management of nail dystrophies (12, 13).

The starting point to manage nail disorders is to understand the nail unit from a functional perspective as two functionally distinctive compartments:

- The support segment consists of the periungual skin and osteoligamentous tissues.

- The germinative segment corresponds to the nail matrix and its products: The nail plate and the nail bed.

These segments are connected through two transitional epithelia: The cuticle and the hyponychium. This statement is reinforced by histologic and immunologic evidence:

- Histologic: The cutaneous portion of the support segment (periungual folds) is similar to other parts of the body skin, while the germinative portion (matrix and nail bed) lacks a stratum granulosum (14).

- Immunologic: The distribution and functional markers of key protagonists of acquired and innate cutaneous immunology differ between the nail matrix and periungual skin. A high density of CD4+ cells is observed in the dermal mesenchyme near the proximal nail fold and hyponychium, while the lowest density of CD4+ is found in the nail mesenchyme surrounding the nail matrix (15). Similar findings are noted for natural killer (NK) cells and mast cells, which are unusually scarce in the vicinity of the nail matrix. Additionally, expression of immunosuppressive factors like insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), alpha melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) is seen in the nail matrix, suggesting a relative immune privilege but potentially affecting its capacity for defense against infections.

- Mechanical: The two functional parts of the nail unit are dynamic, and their movements are determined by their individual keratinization processes and interactions. A change in one part triggers a change in the other one; for example, if the hyponychium is affected by microtrauma, infections, excessive moisture, etc., it can lead to the detachment of the nail plate from the nail bed (onycholysis). When this condition persists chronically, the architecture of the nail bed becomes altered, developing an acral skin-like appearance in a phenomenon known as disappearing nail bed (12). In response to this structural change, the nail plate may undergo compensatory thickening to fit into the reduced nail bed space, because the mitotic activity of the nail matrix remains stable.

It is important to note that the movement of the germinal segment is influenced by several factors: The proximal fold, the adhesion of the nail plate to the nail bed, the containment provided by the lateral folds, and its relationship with the underlying phalanx (16). All these elements contribute to the forward movement of this segment. In contrast, the support segment is not restricted to these factors, allowing for more variability in its movement.

3.1. A Practical Approach to Nail Unit Dystrophy

Nail dystrophy is occasionally the result of a minor insult that was not addressed promptly, such as traumatic onycholysis, cuticle absence, or inflammation of the periungual folds. These disturbances can modify the balance between the two functional segments of the nail unit, potentially impairing nail plate integrity and growth. Therefore, in our experience, restoring the morphology and kinetics of the nail unit is the cornerstone of the effective treatment of nail unit diseases (Figure 1).

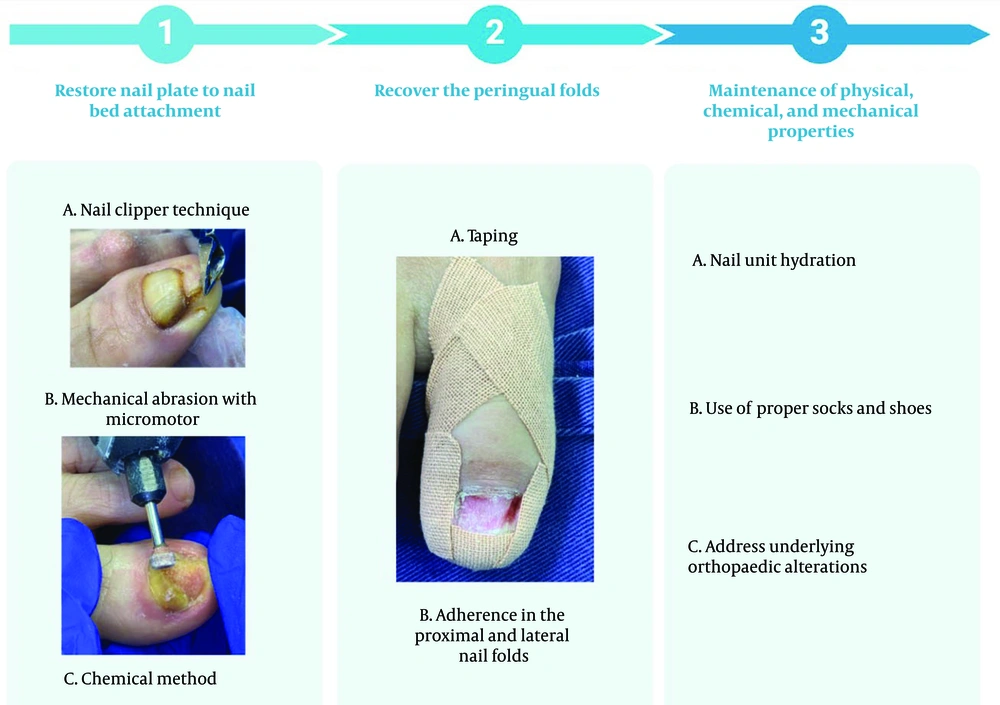

We propose focusing on three key objectives that must be addressed at the same time (Figure 2):

3.1.1. To Restore Nail Plate to Nail Bed Attachment

In patients with onycholysis, the damaged portion of the nail plate or onycholytic band should be trimmed back. If hyperkeratosis is also present, it must be removed. This could be achieved through mechanical or chemical methods:

- Nail clipper technique: Trim the detached portion of the nail plate. Following this, carefully remove any hyperkeratosis and debris within the subungual space, ensuring the cutting edges of the instrument do not come into contact with the nail bed.

- Mechanical abrasion with micromotor or drill: For this procedure, it is recommended to wear an N95 mask, latex gloves, antiseptic alcohol, hydrogen peroxide or saline solution, gauze, and sterile cylindrical tungsten, carbide, or diamond drill bits along with a high-speed micromotor (from 15,000 to 22,000 rpm). Alcohol is applied to reduce the heat generated by the friction between the micromotor and the tissue, as well as to control aerosol and dust dispersion resulting from the pulverization of the nail plate and subungual debris. If the objective is solely to remove hyperkeratosis from the nail bed, care should be taken to avoid bleeding. However, if the goal is the treatment for a “disappeared nail bed”, pinpoint bleeding is necessary. This method is not recommended for beginners, as there is a risk of burns or irreversible damage to the nail bed. A comprehensive description of how this technique is executed can be found in our prior papers (1, 2).

- Chemical method: Apply 40% urea cream daily to dissolve the nail plate within 18 - 20 days. Alternatively, for a supervised approach, the physician applies the cream in a thick layer, protects the surrounding skin, and covers it with an occlusive glove. After 8 days, the occlusion is removed, and the softened nail plate is gently curetted (17).

3.1.2. To Recover the Periungual Folds

- Taping: In the absence of the nail plate, either due to the primary condition or following repair as described in step one, taping should be applied to prevent the interruption of nail growth by the skin and to avoid the keratinization of the nail bed. The key to effective nail unit taping is to retract the periungual folds. Tape should be applied to the medial and lateral folds elliptically to avoid compressing the finger’s vascular supply. At the distal tip, tape should be applied from the dorsal to the volar skin to maintain traction. This technique can be performed with various elastic materials, such as kinesiology tape, Steri strips™, or Medipore dressings™. The choice of material depends on the condition of the nail unit, whether it’s a finger or toe, and the level of force needed to keep the skin away from the nail plate and nail bed area (18). Taping should be continued for as long as necessary for the nail plate to fully grow and reattach to the nail bed. The duration of taping depends on the rate of nail growth and the size of the affected area. Tapes should be replaced whenever they lose the tension needed to retract the folds, typically every one to two days. It is advisable to remove the tape gently, using petroleum jelly to minimize the risk of irritant contact dermatitis.

- Restoration of adherence in the proximal and lateral nail folds: Separation of the nail folds can occur due to microtrauma, aggressive manicures, friction, or excessive moisture. This separation allows areas of the nail unit that should be impermeable to come into contact with water and microorganisms, leading to inflammation of the folds, known as paronychia. If left untreated, this condition can progress to abscesses and even total nail plate dystrophy. A study utilizing 16S rRNA sequencing investigated the key microorganisms associated with inflammation in the periungual folds. The results revealed distinct clusters of skin microbiota in patients with varying severities of inflammation. Severe paronychia was characterized by a higher abundance of anaerobic microorganisms, such as Parvimona, Prevotella, and Peptoniphilus, while Lactobacillus was notably absent. Functional analysis suggests that disturbances in the microbiome may impair microbial metabolism and tissue repair in the skin. We emphasize the importance of restoring the nail unit barrier to achieve a microbial balance, which is important for proper nail plate morphology (19). The objective of this step is to “reseal areas that must remain sealed”. This is achieved by applying hydrophobic polymers, such as cyanoacrylates, copolymer acrylates, or polyvinyl acetate. An appropriate amount is applied every 2 to 4 days to keep the area sealed. Treatment should continue until the folds are fully repaired. Any changes observed in the nail plate, such as Beau’s lines or median canaliform dystrophy, may take longer to resolve, typically around 6 to 9 months.

3.1.3. Maintenance of the Physical, Chemical, and Mechanical Properties of the Nail Unit

- Nail unit hydration: The correct moisturization of the nail unit should consider three factors: Water content, protein structure, and lipid content.

- Water content: A healthy nail contains approximately 18% to 25% water to maintain optimal elasticity. Ingredients like panthenol, urea, lactic acid, and hyaluronic acid increase the water-holding capacity of the nail (5, 6).

- Protein structure: Hydration can modify the molecular structure of the matrix protein. Sulfur-rich ingredients, silicon, and formaldehyde can promote keratin crosslinking (5).

- Lipid content: The nail plate contains approximately 1 - 2% lipids, with cholesterol being the primary component (20). These lipids are essential for retaining moisture within the nail plate. To help replenish lipid levels, oils such as coconut oil, jojoba oil, and borage oil can be beneficial. It is important to avoid solvents found in nail polish removers, as they can deplete these lipids. Although they are not antimicrobial treatments per se, urea and lactic acid may shift pH, facilitate commensal growth, and physically modify the nail plate surface, contributing to a balanced microbiome (10, 21).

- Use of proper socks and shoes: Wearing socks with low friction against the skin reduces shear forces, helping to prevent foot and nail lesions. For active use, synthetic fibers like polyester and nylon are preferred due to their superior moisture-wicking capabilities. While cotton can be acceptable for short durations, it should be changed promptly. When wet, cotton retains heat, which can lead to discomfort and an increased risk of blisters (22, 23). Shoe needs vary greatly and depend on the patient’s foot structure, gait patterns, etc. However, there are general recommendations to help select well-fitting shoes that reduce the risk of nail injuries.

- Roomy toe box: Shoes should provide enough space at the front (10 - 12 mm) or the width of a thumb to avoid crowding and pressure on the toes, preventing nail trauma and ill-fitting footgear that improperly restricts motion during gait, can cause nail unit impingement, repetitive impingement breaks the hyponychial seal and produces onycholysis (24).

- Breathable materials: Shoes made from materials like mesh, nylon, or leather allow airflow, reducing moisture buildup around the nails.

- Avoid tight shoes: Shoes that are too tight or made from rigid materials can damage the nails.

- Address underlying orthopedic alterations: Many nail deformities can develop from untreated musculoskeletal and biomechanical issues, particularly in the feet. It is important to address these conditions to achieve effective long-term outcomes.

3.2. Major Open Questions and How to Answer These

The development of nail dystrophies due to minor traumatic events can delay early diagnosis and treatment, as patients often seek medical help years after the initial injury. This delay complicates treatment strategies and highlights the need for more research into the timing of tissue remodeling that leads to permanent nail damage. Understanding this timeline is essential for optimizing interventions. Another important aspect of managing nail dystrophies is the tendency for changes to persist or recur. The nail unit is highly sensitive to surrounding biomechanical forces, as well as individual comorbidities and lifestyle factors. A thorough, multidisciplinary approach that identifies risk factors and emphasizes patient education is crucial for effectively managing these conditions. Collaboration with orthopedic specialists and physiatrists who have expertise in this area can significantly improve clinical outcomes for affected patients. Our method has some limitations, including the necessity for strict home care and adherence to the previously outlined pharmacological, non-pharmacological, and lifestyle modifications. This adherence must be maintained over a variable but generally prolonged period, due to the slow growth rate of the nails.

3.3. Conclusions

Recognizing the nail unit as a dynamic barrier that adapts to intrinsic and extrinsic factors is essential for effectively treating nail deformities. We present a fresh perspective on how to approach nail unit diseases, particularly nail dystrophies. This approach provides dermatologists with a step-by-step framework based on three key pillars that aim to restore the nail's normal structure and function, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes and nail health.