1. Context

The skin, being the largest organ, provides critical protection for the body from extreme temperatures, mechanical damage, ultraviolet radiation, and microbial infection (1). The complex structure of the skin has three distinct tissues: The epidermis (the outer impermeable layer), dermis (below the epidermis), and subcutaneous tissue (2, 3). The epidermis protects against the entry of water and pathogens. This layer comprises keratinocytes (most abundant), melanocytes, Merkel cells, and Langerhans cells. The epidermis also contains the sebaceous glands, sweat glands, and hair follicles (2). The dermis, which provides tensile and cushioning strength, nutrients, and immunity to the skin, is composed of connective tissue rich in extracellular matrix (ECM), fibroblasts, mechanoreceptors, and vasculature. The dermis provides this cushioning and tensile strength through the ECM of collagen fiber bundles (basket-like arrangement) (3, 4). The subcutaneous adipose tissue, located under the dermis, plays the role of energy storage and serves as a permanent source for growth factors (5, 6). In addition, resident immune cells in each layer constantly check the skin for injury (7). This organ is usually exposed to various injuries, causing wounds. When the skin is injured, several cell types in these three layers must be coordinated in exact steps for healing (8). Normal wound healing lasts about two weeks after the injury; wounds that do not show healing after four weeks are considered abnormal. The elderly, patients with diabetes, and patients suffering from genetic disorders (sickle cell disease, etc.) are vulnerable to defective wound healing.

However, the skin, a dynamic organ, relies on the coordinated efforts of various cell types for repair and regeneration following injury. Among these, hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), traditionally known for their role in hematopoiesis, have emerged as key modulators of wound healing processes. This regenerative capacity arises not only from their plasticity but also from their potent paracrine signaling and immunomodulatory effects.

1.1. Skin Repair Mechanism

Skin repair is one of the most complex processes in the body, involving intricate synchronization of diverse cell types in successive steps (8). Wound closure depends on the depth of the wound and usually occurs about two weeks after the damage. It is assumed that acute wounds pass through certain stages in their healing so that they can be repaired in a specific period (5, 9). It should not take more than four weeks for the first characteristic features of the healing procedure to appear; wounds that do not heal over this time are unlikely to heal in another eight weeks as well (10). Wound healing is a complex process consisting of four interrelated phases: Hemostasis, inflammation, angiogenesis/proliferation, and re-epithelialization (tissue remodeling) (11). Myofibroblasts (originating from fibroblasts) are the most important cells that play a role in wound healing. Myofibroblasts can contract, leading to the contraction of the wound (9, 12). The process of angiogenesis is the main component in wound healing, and many types of cells [endothelial cells, endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs), pericytes, and stromal cells] participate in it. At all steps of wound healing, the most abundant types of inflammatory cells are macrophages/monocytes (originating from HSCs) (11, 13).

1.2. Chronic Wounds

When a loss of skin and related tissues does not undergo the proper healing procedure within the typical timeframe for other wounds to heal, it is called a chronic wound. In these wounds, not all wound areas are in the same stage of the healing procedure. Additionally, cells with altered phenotypes can be observed in them. Such features make properly healing these wounds difficult or impossible (5). Several characteristics of the cells found in chronic wounds include: (1) The morphological characteristics and proliferation potential of these cells are similar to senescent cells, and they express growth factor receptors at low levels (characteristic of hypoxic cells); (2) inflammatory mediators harm the ECM and some growth factors; (3) keratinocytes produce fewer growth factors and show poor migration capacity; (4) there is a reduction in the mitogenic potential of fibroblasts (an important feature) as well as a reduction in laminin332 production (14, 15).

1.3. Treatment of Chronic Wounds by Stem Cells

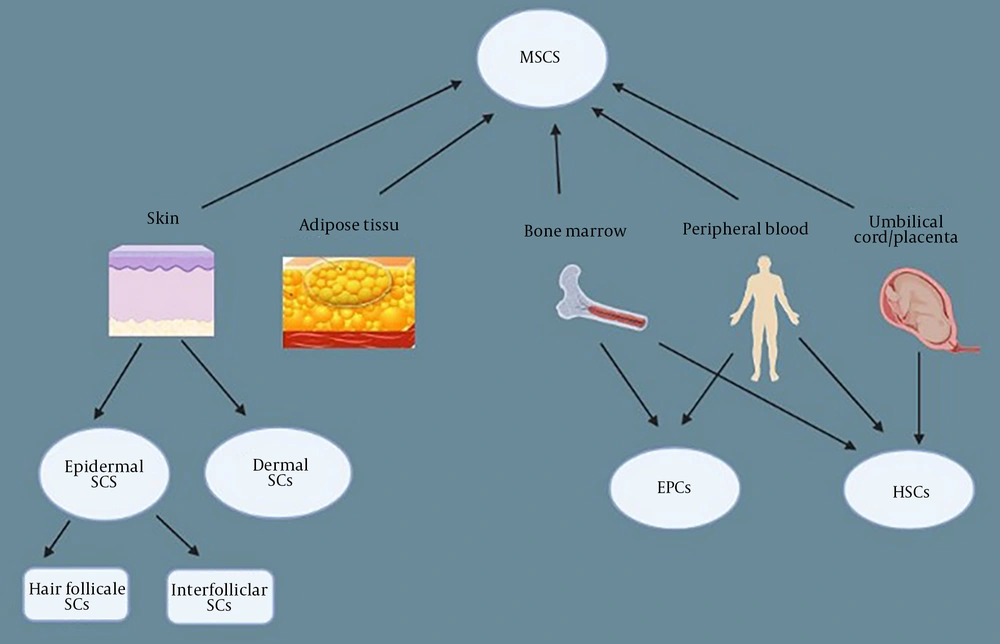

A proper healing procedure for a chronic wound is inhibited at one of its steps or after the injury. In the inflammatory phase of the wound, there are large numbers of early-stage macrophages, neutrophils, fibrin clots, and platelet plugs in the wound bed. The wound healing procedure begins at this stage (16). Without any therapy, inflammatory-related cells (macrophages and neutrophils) remain in the wound bed, and the uptake of endogenous stem cells is impaired, which in turn causes an imbalance in the harmony of the procedure. Granular tissue formation is inhibited due to the absence of myofibroblast differentiation, angiogenesis, re-epithelialization, and collagen deposition (17). Treating these wounds requires special medical skills and can be long-term and challenging (18). New methods of chronic wound therapy include various dressings (occlusive, hydrogel, gauze, etc.), skin grafts, growth factors, and hyperbaric oxygen (19, 20). Although these methods are easy to use and well-studied, they have many limitations and disadvantages that have not significantly impacted the situation and are only moderately effective. Therefore, the necessity for more effective treatments for healing wounds is felt (21). Many other types of therapies, including cell factors, tissue engineering, stem cells, and so on, have been tested by researchers (5, 22). The newest findings show the enormous potential of stem cell therapy in regenerative medicine, such as in the healing of chronic wounds. Stem cells have been shown to increase wound healing through several direct or indirect procedures, such as stimulation of resident cells, releasing growth factors, inflammation, and angiogenesis (23). Using stem cells to treat chronic wounds has many benefits not found in traditional methods. Local or systemic exogenous stem cells mobilize the patient's resident stem cells to participate in the wound healing and granulation tissue (GT) formation process by facilitating angiogenesis (24). Experiments have proven that the administration of stem cells positively affects the biochemistry of the healing process, which speeds up the wound closure period. They not only can proliferate and differentiate but also can increase migration, angiogenesis, and immunomodulation of cells in vivo (25, 26). The main types of stem cells that play a role in wound healing are mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), EPCs, epidermal stem cells, dermal stem cells, and hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells (HP/SCs) (5). Apart from stem cells found in the skin (epidermal and dermal), the other three stem cells (MSCs, EPCs, HP/SCs) are the aqueous portion of the enzymatic digestion of lipoaspirate, which is itself used to treat healing wounds (27, 28) (Figure 1). Hematopoietic and MSCs are the most widely used cells in therapy (29).

1.4. Unlocking the Potential of Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Wound Healing

The HSCs, sometimes called hematopoietic progenitor stem cells (HPCs), are multipotent cells capable of giving rise to all blood cell types. In this manuscript, the term HSCs is used consistently. There are three sources of HSCs: Bone marrow, peripheral blood, and cord blood. These three sources vary by collection methods, cellular composition, and transplantation outcomes (5). The HSCs are, as indicated by their name, progenitors of most blood cells with the ability for self-renewal and differentiation to form red blood cells, platelets, and white blood cells (30, 31). Most HSCs are CD45 marker positive, and some also express CD34. Since MSCs lack such markers, CD34 and CD45 distinguish between HSCs. The most common type of stem cell in the bone marrow is the CD34+HSC, which can be extracted from either peripheral blood or bone marrow (32-34).

The skin regeneration potential of the HSCs is due to their involvement in the angiogenesis procedure and their high plasticity (35). Chimerism of the skin (i.e., donor-derived epithelial cells in the recipient) has been observed after HSC transplantation (BM or PBMC), supporting the hypothesis of HSC plasticity and their therapeutic role in chronic wound regeneration (36-38). In addition to their plasticity, HSCs play a critical role in angiogenesis, as shown in myocardial infarction models, which supports their involvement in wound vascularization and tissue repair (39).

Mature HSCs are traditionally classified into two lineages: Myeloid and lymphoid. The lymphoid lineages include T, B, and natural killer (NK) cells, whereas the myeloid lineage includes neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, erythrocytes, megakaryocytes, and granulocytes. Myeloid-derived cells, such as monocyte-derived macrophages and neutrophils, are crucial in the inflammatory and remodeling phases of wound healing (40, 41). Current studies emphasize this significant role of myelopoiesis, and a deficiency in this may delay the healing of the wound, especially in chronic inflammation (13).

Mechanistically, HSCs control the wound microenvironment via multiple pathways. They promote macrophage polarization from the pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, facilitating tissue remodeling and inflammation resolution. This phenotypic conversion is regulated by cytokines such as IL-10 and TGF-β secreted by HSCs following injury (42, 43). The HSCs also regulate ECM remodeling. They inhibit matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), halting spontaneous degradation of collagen, and at the same time secrete collagen and stimulate fibroblast proliferation, thereby facilitating dermal reconstruction (17). The two-handed effect — suppression of MMPs and collagen synthesis — is likely context-dependent and varies between acute and chronic wound models (e.g., diabetic ulcers and traumatic wounds) (44).

The interaction of mesenchymal and epithelial cells is a critical phenomenon in the differentiation and proliferation of keratinocytes, which may play an important role in re-epithelialization and cutaneous wound healing. The expression of CD133 and CD34 cells in dermal fibroblasts and follicular matrix during embryogenesis is evidence of the role of HSCs in controlling molecular aspects of epithelial-mesenchymal cell interactions (45).

However, while preclinical data are growing, the use of HSCs for wound healing has not yet been thoroughly explored clinically. Few trials have examined their direct therapeutic use, and challenges such as viability, homing to the hypoxic wound bed, and immune compatibility must be addressed. There are few comparative studies between HSCs and other stem cells like MSCs. Since both cell types have immunomodulatory and regenerative capabilities, future research will need to elucidate their relative efficacy in models of chronic wounds (46). Notably, several types of stem cells have already been applied for skin regeneration, as summarized in Table 1, supporting the rationale for considering HSCs as potential alternatives. The HSCs are also hypothesized to have applications beyond wound healing, such as in stroke, muscular dystrophy, and cystic fibrosis. Such potential applications, however, are only speculative and must be proven rigorously.

| Stem Cells | Context of Study | Clinical or Preclinical | Number of Patients and Interventions | Main Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSCs | Experimental evaluation of the effectiveness of applying CD93 HSCs with PCL‐gelatin scaffold, in diabetic wound healing in a rat model | Rat model | Forty clinically healthy Wistar rats | Co-application of CD93+HSCs with PCL‐gelatin nanofiber scaffold significantly promotes the healing of diabetic wound (47). |

| HSCs | Assessment of feasibility, safety, and potential impact of stem cells on chronic wounds through a pressure sore model | Pilot study phase I/II study | Cohort of 5 patients in pilot study | Facilitated healing of uncomplicated wounds, improved healing outcomes for complicated (chronic, non-healing) wounds (48). |

| BMMSCs | Autologous stem cells from bone marrow, used to accelerate pressure ulcers healing in patients suffering from SCI | Observational study | Twenty-two SCI patients suffering from stage IV pressure ulcers lasting over 4 months | Full healing of longstanding stage IV pressure ulcers in 19 of the 22 patients (86.36%) with spinal cord injury after a mean time of 21 days; hence, BMMNCs could be a promising treatment stage IV pressure ulcers (49). |

| BMMSCs | Therapeutic application of autologous bone marrow aspirate for skin tissue engineering and tissue regeneration | Case-control study | Out of 75 chronic wound patients, 50 patients received BM aspirate or cultured BM as a treatment, and 25 were given daily saline dressings were used as controls. | Patients treated with Cultured BM cells exhibited a significantly higher percentage reduction in wound size compared to those received freshly applied BM aspirate and normal saline dressing (50). |

| BMMSCs | Local delivery of autologous mBMC, obtained from bone marrow aspirate | Case report | A type 2 diabetic patient suffering from chronic venous disease and neuro-ischemic complications | Following 7 d of treatment, there was a significant reduction in the size of chronic venous and neuroischemic wounds, along with the enhanced vascularization, and mononuclear cells infiltration (51). |

| BMMSCs | Application of marrow-derived stem cells to promote the healing process in chronic wounds | Case series report | Three cases with complex lower extremitychronic wounds | Reduction size of chronic wounds in 3 patients (100%) of different etiologies, may be a useful and safeadjunct to wound simplification and ultimateclosure. |

| Progenitor cell | Pilot study of progenitor cell therapy for sacral pressure ulcers using a novel human chronic wound model | NCT00535548 clinical trial | Three patients | Decreased chronic wound size of 50% (all patients: 3) over 3 wk of therapy (n = 3 patients) (52). |

| BMMNCs | Exposure to bone marrow cells and using subsequent epidermal sheet grafting in patients with chronic wounds caused by diabetes mellitus | Nonrandomized controlled trials | Twenty patients | Epidermal grafting led to a significant acceleration in the healing of diabetic foot ulcers (P = 0.042) without exposed bones, along with site-specific differentiation (53). |

| BMMNCs | Evaluation of the potential of autologous bone marrow-derived cells for healing chronic wounds in the lower extremities | Randomized clinical trial | Out of the 48 patients in the study, 25 were randomized to receive the study treatment and 23 to the control treatment. | A single dose of autologous bone marrow-derived cells accelerates the healing process and reduced wound area by 17.4% (n = 25 patients) at 2 wk, compared to 4.84% decrease in the control group (n = 23 patients) for chronic lower extremity wounds during the early phase of treatment (54). |

| BMMNCs | Management of human chronic wounds with application of autologous ECM/stromal vascular fraction gel | A STROBE-compliant study | Twenty patients | The ECM/SVF gel group exhibited an average weekly wound healing rate of 34.55 ± 11.18%, while the negative pressure wound therapy group showed a rate of 10.16 ± 2.67% (P < 0.001) that shows ECM/SVF gel was effective (55). |

| WJSCs | The healing effects of Wharton's jelly-derived stem cells onto biological scaffold for chronic skin ulcers | Randomized clinical trial | Five patients ranging from 30 to 60 years old, with chronic diabetic wounds | The wound healing time and wound size significantly decreased, in chronic diabetic patiants, and 6 and 9 days post-treatment, the wound size significantly diminished (P < 0.002), suggesting that amniotic membrane- seeded WJSCs could play a key role in accelerating the healing process in them (56). |

Abbreviations: HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells; PCL, polycaprolactone; BMMSCs, bone marrow mononuclear stem cells; mBMCs, mononuclear bone marrow cells; UCSCs, umbilical cord Wharton's jelly stem cells.

1.5. Wound-Healing Potential of Human Umbilical Cord Blood and Peripheral Blood

The umbilical cord carries oxygen and nutrients from the mother to her fetus. While once human umbilical cord blood (HUCB) was considered medical waste, it is now recognized as a valuable source of stem cells. The cord blood is collected after birth from the umbilical cord for preservation and later use (57). The HUCB, which is a rich resource of hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs), is increasingly used in the treatment of various diseases. The HUCB differentiates into both hematopoietic (erythroid, myeloid, and lymphoid) and non-hematopoietic (epithelial, endothelial, and mesenchymal) progenitor cells (58, 59).

Several factors exist in the human umbilical cord that can induce cell proliferation, migration, growth, and tissue differentiation (60). Umbilical cord blood and peripheral blood are enriched with progenitor cells expressing CD133 and CD34 markers. These multipotent cells exhibit neovascularization potential in ischemic models. It has been reported that CD133+ or CD34+ cells can accelerate wound closure in preclinical models (61, 62). The evidence shows that HUCB cells can heal wounds as well as traumatic bone injuries. In a study, HUCB-derived CD34+ cells were used for treating skin wounds that were resistant to conventional treatment (for example, surgery) for one year. After using cord blood, the wound was healed in 2 patients. Moreover, no graft versus host disease (GVHD) was observed after follow-up for 3 - 7 months. However, the lack of statistical power in such small-scale studies limits their generalizability and calls for cautious interpretation (63, 64). The ability of cord blood-derived CD34+ cells expanded by nanofibers has been demonstrated in an in vitro cellular model as well as in a mouse excisional wound model. After systemic use, they reach the wound bed and can facilitate the procedure of wound healing. It has been demonstrated that wound healing is accelerated via cord blood-derived CD34+ cell treatment. These cells at the wound bed inhibit some matrix MMPs, which in turn prevent collagen degradation and enhance the amount of collagen components in the wound bed (65). In another study, unlike the previous experiment, it has been demonstrated that cord blood-derived CD34+ stem cells expanded by nanofiber can speed up wound closure through secreting collagen, thus positively participating in the ECM, which indicates that treatment with CD34+ stem cells has the potential to heal refractory wounds caused by traumatic skin injuries or diabetes (66). Lymphocytes derived from HUCB are immunologically naïve and can produce only a small number of activating cytokines. Studies have also indicated that HUCB cells have the capacity for differentiating into chondroblasts, keratinocytes, adipocytes, osteoblasts, and hematopoietic cells (58, 59).

In the case of peripheral blood, it has also been shown that the healing of thick skin lesions in diabetic mice was accelerated by human CD34+ peripheral blood mononuclear cells, which in turn speed up revascularization and epidermal healing (67). Similar results were found in a report in which treatment with cord blood-derived CD34+ cells (in a paracrine manner) accelerated wound healing in diabetics by promoting fibroblast proliferation, stimulating keratinocytes, and enhancing neovascularization (67). These findings suggest that skin lesions in complex pathological conditions (such as diabetes) may be treated using the therapeutic potential of blood-derived progenitors.

1.6. Comparative Analysis of Hematopoietic and Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Skin Regeneration

Among the different cell-based therapies under investigation, HSCs and MSCs are two of the most commonly explored. A comparison between HSCs and MSCs highlights each cell type's specific advantages and limitations in the context of wound healing and skin regeneration. Both HSCs and MSCs possess key therapeutic properties, including paracrine signaling through the secretion of growth factors and cytokines, immunomodulatory activity, and tissue regenerative capacity. However, notable differences exist in source accessibility, differentiation potential, and clinical safety profiles (68, 69).

The MSCs, predominantly isolated from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and the umbilical cord, exhibit broad mesodermal differentiation potential and can give rise to osteoblasts, chondrocytes, and adipocytes. These cells have demonstrated significant safety and efficacy in numerous preclinical and clinical studies, leading to their widespread application in tissue regeneration, particularly in cutaneous repair. Their anti-inflammatory properties and ability to stimulate fibroblast proliferation and activity are among the key mechanisms through which MSCs accelerate healing in chronic wounds such as diabetic ulcers (70).

The HSCs, on the other hand, are primarily committed to hematopoietic lineages and play a critical role in reconstituting and maintaining the hematopoietic system. Studies have indicated that HSCs can contribute directly to angiogenesis and the modulation of immune responses — features that support their potential as adjunctive agents in tissue repair and wound healing. Despite increasing preclinical and emerging clinical evidence supporting the efficacy of HSCs in wound healing, direct comparative studies between HSCs and MSCs remain limited. No head-to-head clinical trials have been published that systematically evaluate their relative effectiveness in wound healing settings (71). Table 2 summarizes the key features, mechanistic distinctions, and clinical applications of HSCs and MSCs based on current evidence.

| Feature | HSCs | MSCs |

|---|---|---|

| Primary sources | Bone marrow, peripheral blood, and cord blood | Bone marrow, adipose tissue, umbilical cord, and placenta |

| Lineage potential | Hematopoietic (myeloid and lymphoid) | Mesenchymal (osteocytes, adipocytes, and chondrocytes) |

| Role in wound healing | Angiogenesis, immune modulation, and ECM regulation | Immunomodulation, fibroblast activation, and re-epithelialization |

| Marker expression | CD34+, CD45+, and CD133+ | CD90+, CD73+, and CD105+ (lack CD34/CD45) |

| Immunogenicity | Generally low, especially in UCB-derived cells | Low, immune evasive properties |

| Clinical use in wounds | Emerging evidence; limited trials | Multiple trials, especially for chronic wounds |

| Mechanistic focus | Macrophage reprogramming (M1→M2) and cytokine secretion | Anti-inflammatory, pro-angiogenic, and ECM remodeling |

| Limitations | Homing inefficiency and less clinical data | Risk of senescence and source variability |

Abbreviations: HSCs, hematopoietic stem cells; MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; ECM, extracellular matrix; UCB, umbilical cord blood.

1.7. Challenges and Clinical Considerations in Hematopoietic Stem Cell-based Therapies

Despite promising preclinical data, the clinical application of HSC therapies in wound healing faces serious biological and practical challenges. A significant limitation in allogeneic transplantation is that HSCs may induce GvHD, particularly in partially or mismatched donor-recipient histocompatibility. The incidence of GvHD in incompatible grafts is up to 70%, requiring long-term immunosuppressive therapy, the development of which is hazardous and the completion of which is detrimental to wound healing mechanisms (72, 73).

Apart from immunologic challenges, the practical clinical function of HSCs is equally dependent on their ability to home to the target wound and engraft into damaged tissue. While dominant chemokine receptor axes, such as SDF-1/CXCR4, have been identified as the central axis of this process, efficient trafficking of HSCs to peripheral injury sites remains suboptimal outside the bone marrow environment. Poor homing reduces therapeutic gain and may necessitate local delivery systems or tissue scaffolds (74). Moreover, the pro-inflammatory microenvironment of chronic wounds or hypoxia further inhibits cell survival and colonization. Preconditioning, hydrogel encapsulation, or 3D culture systems have been investigated to promote survival and engraftment. However, they are currently mostly in preclinical stages and require further evaluation with clinical trials.

There is a theoretical concern regarding tumorigenesis, particularly when HSCs undergo high degrees of ex vivo manipulation, such as gene editing or long-term expansion. Although clinical evidence has not yet shown a significant carcinogenic risk, careful observation and long-term follow-up are necessary (75).

Collecting HSCs also raises clinical concerns, especially with autologous therapy. Donor mobilization with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) is a standard method for concentrating peripheral blood HSCs. However, it is associated with side effects such as bone pain, splenic rupture, transient leukocytosis, and acute respiratory distress. Such side effects require careful clinical monitoring and may limit the use of autologous protocols in vulnerable patients (76).

Finally, regulatory and ethical issues also pose challenges to clinical applications. Allogeneic HSC therapies carry immunological and donor-related risks, while agencies highly regulate stem cell-based products. The availability of standardized cell preparations, quality control, and potency assays remains a significant barrier to widespread clinical use. There is a need for a concerted effort to develop reproducible and safe clinical-grade HSC products, with robust data from controlled trials to demonstrate efficacy in both acute and chronic wound models (77).

Despite promising preclinical data, the scientific literature on HSC-mediated wound healing is somewhat inconsistent. While several studies report increased angiogenesis, accelerated GT formation, and improved wound closure, others — especially in chronic wound models like diabetic wounds — fail to demonstrate statistically significant improvements. Discrepancies may arise from variations in animal models, transfer methods, and definitions of clinical endpoints. Additionally, the heterogeneity of HSC preparations and differences in patient immune status complicate the comparison between studies (78).

These gaps in the literature highlight the importance of standardized protocols, larger clinical trials, and rigorous mechanistic studies to establish the reliability and reproducibility of HSC-based interventions in different wound settings.

2. Conclusions

Despite the several treatment options currently being used, chronic wounds remain a significant concern for healthcare specialists. The HSCs are responsible for producing effector innate immune cells such as neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages. Dysfunction of HSCs is associated with risk factors for non-healing wounds related to diabetes, obesity, atherosclerosis, chronic infection, and aging. It has also been found that patients with chronic wounds or non-healing wounds are at high risk of developing chronic inflammatory conditions. Various studies demonstrate that the biochemistry of the healing process has been positively affected by administered HSCs and that they can shorten the time of overall wound closure. Not only do they proliferate and differentiate, but they can also stimulate cells in vivo for immunomodulation, migration, and regeneration via the paracrine procedure. Wound healing by HSCs can be enhanced by joint cultures, as well as by applying proper scaffolds.

Despite promising preclinical data, the scientific literature on HSC-mediated wound healing is conflicting. While several studies report increased angiogenesis and accelerated wound closure, others — especially in chronic models such as diabetic wounds — do not show significant improvement. Such discrepancies emphasize the need for more standardized protocols and mechanistic studies. To uncover details of the mechanisms linked to stem cells' action, further research is needed to ensure the safety of their use and increase their therapeutic efficacy in treating patients. Future research should focus on clarifying the context-dependent effects of HSCs — particularly their interaction with different wound microenvironments. Investigating HSC homing efficiency, paracrine signaling, and survival under hypoxic conditions will be critical to optimizing their therapeutic potential.