1. Introduction

Mycetoma is characterized by a triad of tumefaction (large painless tumor-like swellings), draining sinuses, and discharge containing grains. It is more commonly reported from the mycetoma belt, which includes tropical and subtropical regions between 30°N and 15°S (1). The incidence is higher following trauma in agricultural workers who walk barefoot in the fields. Mycetoma is caused by both fungi (eumycetoma) and filamentous bacteria (actinomycetoma) (2). The causative organisms of actinomycetoma include Actinomadura, Nocardia, and Streptomyces. Nocardial actinomycetoma is prevalent in developing countries and is a chronic suppurative granulomatous disease involving the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

Nocardial actinomycetoma begins as a small painless nodule, and the patient may recall an injury to the site. Over the years, soft tissue swelling and multiple nodules develop, which ulcerate and drain through sinuses. It is associated with serosanguinous to purulent discharge containing grains. These may be manifestations of eumycetoma, actinomycetoma, botryomycosis, primary cutaneous actinomycosis, and atypical mycobacterial infection. These differentials pose a diagnostic dilemma. In such cases, appropriate clinical acumen and early laboratory evaluation are necessary for early diagnosis and to prevent complications. Our case report describes nocardial actinomycetoma at a rare site in a non-endemic region of Maharashtra, India.

2. Case Presentation

A 62-year-old male patient from central Maharashtra, an agricultural worker by occupation, presented with the chief complaints of swelling and reddish elevated lesions with discharge around the right knee for the past two years. These lesions became painful and gradually evolved into discharging sinuses. The patient reported a history of intermittent fever associated with chills and rigor. He had suffered trauma to the right knee six years ago and had taken multiple antibiotics from outside sources with partial relief. There was no history of cough with expectoration, weight loss, or similar lesions elsewhere on the body.

On examination, the patient was vitally stable with no pallor, icterus, cyanosis, clubbing, lymphadenopathy, or edema. Systemic examination was within normal limits. Dermatological examination revealed diffuse swelling around the right knee joint, involving the right lower thigh and right lower leg. Multiple erythematous to hyperpigmented papules and nodules with 3 - 4 puckered scars were present over the swelling. Multiple discharging sinuses with purulent discharge were observed, and crusting was present over a few papules and nodules (Figure 1). On palpation, tenderness was noted. There was no regional lymphadenopathy. A clinical differential diagnosis included actinomycetoma, eumycetoma, actinomycosis, botryomycosis, and cutaneous tuberculosis.

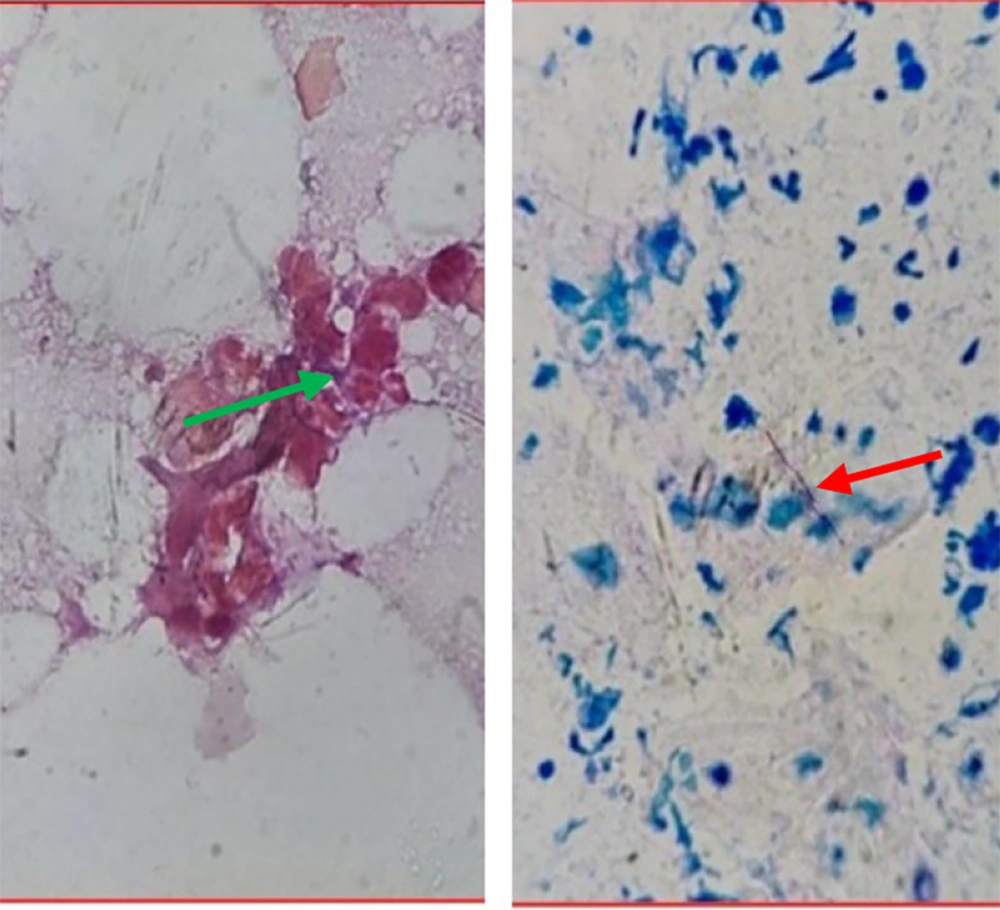

Discharge from multiple sinuses was collected, smeared on sterile glass slides, and sent to the laboratory for 10% KOH (potassium hydroxide) mount, Gram stain, and Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stain. The KOH mount was negative for fungal filaments, while the Gram stain showed Gram-positive filamentous bacilli (Figure 2, left). The ZN stain was negative, but Kinyoun’s modification with 1% sulfuric acid (Modified ZN stain) showed positive partially acid-fast filamentous bacilli (Figure 2, right). The discharge was also sent for culture and sensitivity testing. It was inoculated onto Lowenstein-Jensen (LJ) medium, with no growth despite repeated attempts.

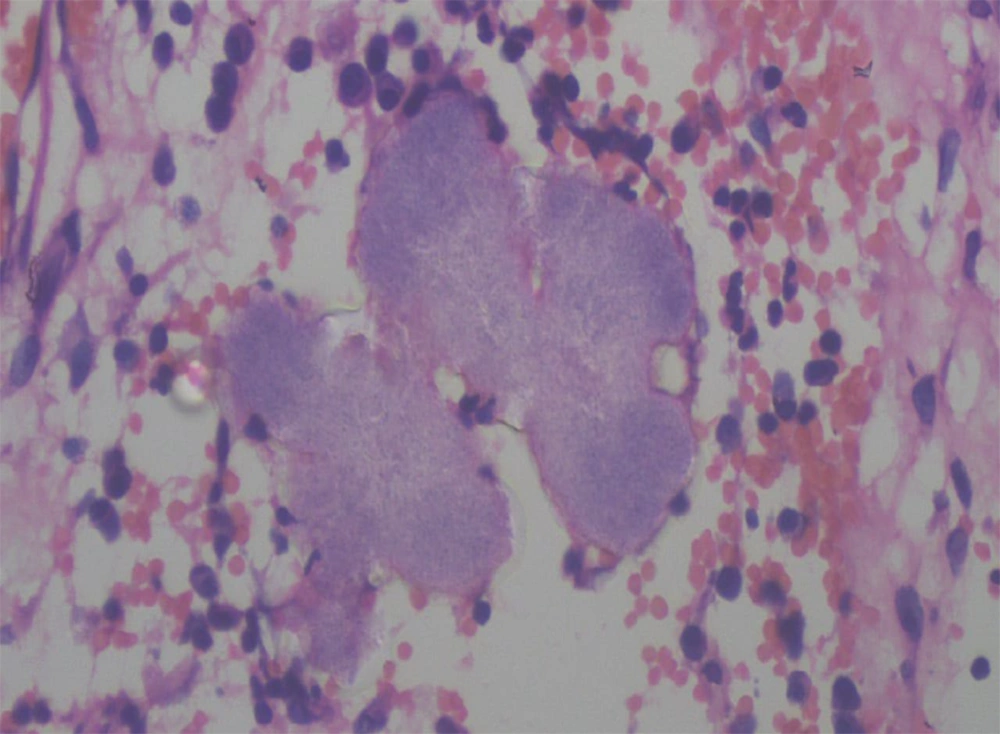

On histopathology, the subcutaneous tissue showed granulation with dense infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and polymorphs, with a focal area of granulomatous reaction comprised of histiocytes and lymphocytes. Actinomycotic colonies showed multiple closely-packed granular, not easily discernible interlacing filaments with surrounding epithelioid cell granuloma (Figure 3).

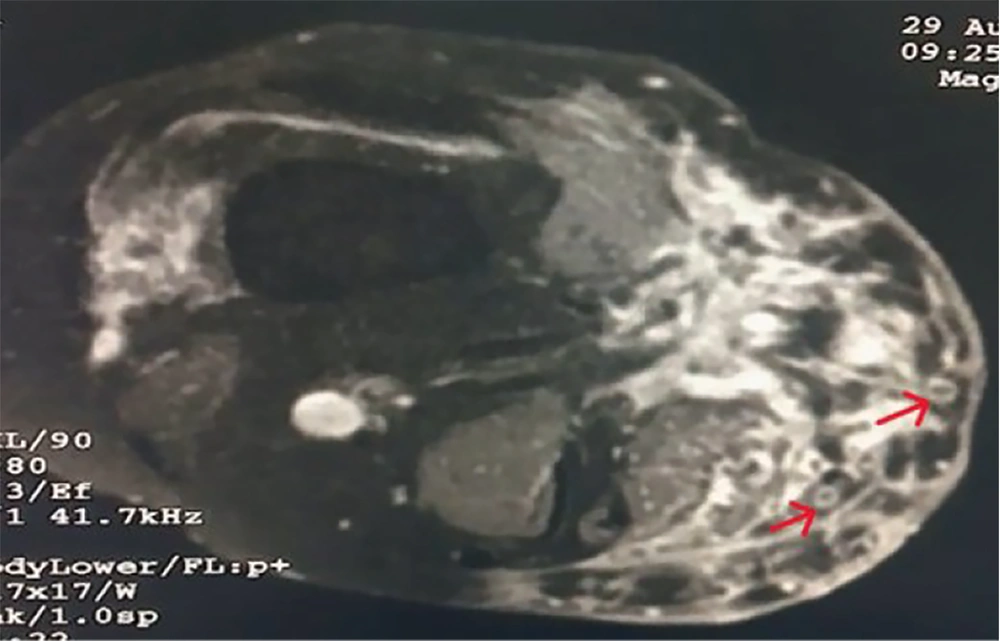

Radiological examination of the right knee included a local X-ray, which showed subcutaneous soft tissue swelling in the right knee joint region with heterogeneity, more pronounced on the medial aspect. Findings from the local ultrasound (USG) revealed multiple hypoechoic, interconnecting tracts, some of which were opening onto the skin. Diffuse subcutaneous thickening was noted involving the right knee joint. MRI (plain and contrast) was suggestive of heterogeneous altered signal intensity in areas involving the anteromedial aspect of the lower thigh, knee, and upper leg, with extensions and a peripheral hyperintense (circle) with a central hypointense area, known as the ‘Dot in circle sign’ (Figure 4).

Based on clinical, microbiological, radiological, and histopathological findings; diagnosis of nocardial actinomycetoma was made. Patient was treated with a combination therapy (Modified Welsch regimen) consisting of Injection Amikacin 15mg/kg/day intravenously (IV) in two divided doses with oral trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole) 35mg/kg/day and oral rifampicin 10mg/kg/day. Injection amikacin for 21 days constituted one cycle. Two such cycles were administered at an interval of 15 days. Oral co-trimoxazole and rifampicin were given daily without interruption. The size of the lesions and the discharge were reduced after a single cycle of amikacin. By the end of second cycle, all lesions had dried up and with no discharge observed. A few lesions were healed with post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation (Figure 5). He completed two cycles of therapy but was subsequently lost to follow-up.

3. Discussion

Mycetoma is a neglected tropical disease and can be caused by both fungi (eumycetoma) and bacteria (actinomycetoma) (2, 3). Nocardial infections occur worldwide particularly in tropical and subtropical areas. Most frequent primary site of involvement is pulmonary (73%). Dissemination can occur to other organ systems. Secondary sites are brain (45%), meninges and spinal cord (23%), skin and subcutaneous tissue (9%), pleura and chest wall (8%) (4). Primary cutaneous nocardial infections occur due to direct implantation of pathogenic Nocardia from soil to the skin. Its incidence was reported as 5% in western literature, although data regarding overall incidence of primary nocardiosis was not available in India as only few cases have been reported. Primary cutaneous nocardial infections are divided into (A) primary cutaneous nocardiosis (cellulitic and Sporotrichoid forms), (B) actinomycetoma caused by Nocardia, (C) disseminated disease (secondary to pulmonary involvement) (5).

Nocardia accounts for 90% of actinomycotic mycetoma cases in South and Central America and Mexico (6). The number of reports of nocardial infection is limited in India, though it has been documented in Himachal Pradesh, Mumbai, and Karnataka. Actinomycotic mycetoma due to Nocardia was found in 21% of cases in a study from Madras (7). Sharma et al. reported four cases of actinomycotic mycetoma caused by Nocardia from Himachal Pradesh (8). In a study from central India, 7 out of 11 cases were of actinomycotic mycetoma diagnosed on histopathological examination (9). In the Indian scenario, common organisms causing actinomycetoma are A. madurae and A. pelletieri. In a study from Pune, Maharashtra, a total of 18 cases of actinomycetoma were reported, out of which 3 were nocardial actinomycetoma. The most common site of mycetoma is the foot. A single case of actinomycetoma caused by A. madurae has been reported on the thigh (10). Two cases of actinomycetoma over the knee have been reported from central India, though the causative organism could not be identified (9).

Our patient presented with swelling and multiple discharging sinuses of chronic duration around the right knee, typically seen in mycetoma. Nocardial mycetoma is usually associated with white grains (size 80 - 130 μm) (11). It may present without grain formation, as seen in our case, where only purulent discharge was present without granules. Several staining techniques are used for the rapid identification of causative agents of mycetoma. The causative organisms of actinomycetoma are Gram-positive filamentous bacilli. The Modified ZN staining technique is superior in discriminating between actinomycotic agents; Actinomadura spp. and Streptomyces somaliensis are ZN negative, while Nocardia spp. are ZN positive. In our case, Gram-positive filamentous bacilli were seen on Gram staining, while on Modified ZN staining, partially acid-fast filamentous bacilli were observed, suggesting Nocardia as the causative organism. However, microscopy has low sensitivity and specificity.

The discharge was also sent for culture on LJ medium, but the organism failed to grow. Identification of the organism was challenging in our setup due to limited resources, the stringent growth requirements of the organism, and the partial treatment the patient received from outside sources. On histopathological examination, the colony morphology was consistent with Nocardial actinomycetoma (12).

Radiological examination revealed subcutaneous soft tissue with heterogeneity. Early bone involvement is more common in actinomycetoma compared to eumycetoma. Although MRI has high sensitivity for diagnosing mycetoma, with the ‘Dot in circle’ sign seen in both actinomycetoma and eumycetoma, it cannot identify the causative organism (13).

The patient was treated with the Modified Welsch regimen, consisting of amikacin, co-trimoxazole, and rifampicin (10). Multidrug therapy was preferred in our case to avoid drug resistance and reduce residual infection, as the patient had previously taken multiple antibiotics with partial relief. Amikacin is an aminoglycoside that irreversibly binds to the 30S subunit of the bacterial ribosome, blocking protein synthesis in bacteria. Co-trimoxazole inhibits the conversion of folic acid into its active form, tetrahydrofolate, ultimately inhibiting bacterial growth. Rifampicin acts on DNA-dependent bacterial RNA polymerase and has been reported as a good second-line drug for actinomycetoma (14). Our patient showed a good clinical response after this combination therapy without any notable adverse effects.

Nocardial actinomycetoma poses a diagnostic challenge. Although Nocardia is a rare pathogen, it deserves consideration in the etiological differential diagnosis of mycetoma. Astute clinical examination combined with prompt laboratory evaluation can facilitate an accurate diagnosis. Early identification and timely initiation of effective and specific therapy are crucial for achieving a favorable outcome and preventing complications.