1. Background

Infants born between 20 and 37 weeks of gestation are classified as preterm, accounting for approximately 11% of global births (1). Each year, more than 15 million preterm infants are born worldwide, representing over 1 in 10 births (2). In Iran, the rate is even higher, with nearly 12% of all births classified as preterm (3). Numerous factors contribute to preterm births, including maternal demographics and lifestyle choices (4).

Although some risk factors are difficult to prevent, early and cost-effective interventions can save up to three-quarters of preterm infants' lives. Unfortunately, these infants often face challenges in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), which are stressful environments characterized by pain and prolonged separation from parents. Such conditions negatively impact the sensory and environmental experiences essential for normal growth and development (5). As a result, preterm infants may experience complications in physical, cognitive, neurodevelopmental, behavioral, and motor domains (6, 7). Delayed motor development is common among these infants, highlighting the need for timely interventions (8).

Medical treatments in NICUs often include invasive procedures and medications. While these interventions are necessary for survival, they can have negative side effects. Rehabilitation professionals, including occupational therapists, play a vital role in the NICU by helping to prevent secondary complications and supporting normal growth and development (9).

Occupational therapists emphasize non-pharmacological methods tailored to the developmental needs of vulnerable infants, adopting a holistic approach that considers the individual, their environment, and daily activities. Techniques such as jaw muscle strengthening (10) and strategies to reduce sensory stimuli, like light and sound, help create a calm atmosphere to improve sleep (11). Occupational therapists also focus on nutrition and sleep, engaging parents and NICU staff to implement these techniques and alleviate infants' discomfort (12). Additionally, occupational therapists collaborate closely with speech therapists, whose interventions promote earlier transitions to oral feeding in preterm infants (13). As research on occupational therapy (OT) in NICUs expands, it is crucial to continually reassess and integrate evidence-based practices to enhance developmental outcomes for preterm infants.

Among various non-pharmacological interventions, music therapy has gained attention for its positive impact on brain function and structure (14). Music stimulates multiple brain regions and triggers beneficial physiological responses. It has been shown to expand certain cortical areas, such as enhancing the anterior corpus callosum, which is vital for complex motor tasks (15, 16). Furthermore, music enhances sensory processing, emphasizing its importance in the development of preterm infants (17). Thus, integrating music therapy into NICU care may significantly benefit neurological, motor, and sensory development.

In addition to its neurological effects, music serves as a meaningful therapeutic medium in OT. It supports sensory integration, emotional regulation, and engagement in purposeful activity, which are core components of occupational performance. The structured and rhythmic qualities of music align with OT principles that emphasize participation, regulation, and interaction through creative and meaningful experiences (18). This framework positions music not only as a sensory stimulus but also as a tool for promoting interaction, bonding, and early developmental participation.

The primary novelty of this study is its systematic investigation of the effect of music therapy within the specific context of an Iranian NICU, addressing a key cultural and contextual gap in the existing literature. Despite extensive global evidence supporting the benefits of music therapy for premature infants, its systematic application and evaluation within Iranian NICUs remain largely unexplored.

Most previous studies have been conducted in Western healthcare systems, where cultural practices, parental involvement, and environmental conditions differ significantly from those in Iran. Factors such as higher ambient noise levels, limited parental presence due to institutional policies, and different staffing structures may influence how music therapy functions in Iranian neonatal settings (19). Furthermore, this study adopts an OT framework, focusing specifically on functional developmental outcomes rather than purely physiological measures. While previous research has emphasized parameters such as weight gain, heart rate, or oxygen saturation, this study evaluates occupational performance domains.

Previous studies have demonstrated that music interventions in NICUs can yield several positive outcomes, including improved movement planning, reduced noise levels, decreased anxiety, weight gain, and better sleep quality (20). These benefits collectively contribute to shorter hospital stays and reduced healthcare costs. Music therapy also enhances cognitive and sensory functions, leading to improved daily functioning (21). It has been shown to lower heart rates, increase oxygen saturation, and foster emotional bonds between parents and infants (22). Systematic reviews confirm that music therapy can reduce stress and pain in preterm infants, leading to improved developmental outcomes and earlier discharges. Furthermore, parental involvement in music therapy has been associated with reduced anxiety and better bonding, making it a valuable, cost-effective approach in neonatal care (23, 24).

Therefore, incorporating music therapy into standard NICU care offers a low-risk, high-benefit strategy to support vulnerable newborns and their families. This perspective reinforces the integration of music within OT practice as a creative and evidence-based approach to promoting engagement and functional development (18).

The principles of OT emphasize rhythm and timing in daily functioning. External rhythmic stimuli, such as music, can positively influence internal behavioral organization (25, 26). Previous clinical trials have demonstrated encouraging results. For example, a study comparing live versus recorded music found that live music reduced heart rates and promoted deeper sleep in stable preterm infants (27). Another study on music stimulation reported increased weight gain and shorter hospital stays (28).

Despite these findings, rigorous, context-specific evidence from Iran remains scarce. The present study pioneers this area by generating localized, evidence-based data that can inform neonatal OT practice, guide culturally appropriate intervention design, and establish a foundation for future clinical protocols in Iranian NICUs.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the effects of music therapy on the occupational performance of premature infants in the NICU. It addressed the gap in systematically applying music therapy in the Iranian healthcare context. By rigorously examining motor and behavioral functions in preterm infants, the research sought to provide critical insights into the potential benefits of music therapy. Building on previous research demonstrating that music therapy can improve activity levels, alertness, and neuromotor development in newborns (29), this study was grounded in motor development theory and rehabilitation approaches relevant to OT (30).

The central hypothesis proposed that music therapy would enhance motor performance, improve sleep quality, reduce anxiety, and support weight gain in premature infants. In alignment with this hypothesis, the primary outcome of the study was defined as changes in behavioral regulation measured through Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale (NBAS) domains, including state regulation, habituation, autonomic stability, and social interaction. The secondary outcome was defined as motor performance assessed using the test of infant motor performance (TIMP).

Additionally, it was expected that integrating music into NICU care would shorten hospital stays and reduce healthcare costs. Given the limited research on music therapy in Iranian NICUs, this study holds particular importance for developing culturally appropriate interventions that address the unique developmental needs of preterm infants and advance neonatal care outcomes.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

This research employed a randomized clinical trial design to systematically investigate the effect of music therapy on the occupational performance of premature infants admitted to the NICU at Akbarabadi Hospital, affiliated with the Iran University of Medical Sciences.

3.2. Participants

The study included a total of 40 infants, evenly divided into two groups: Twenty in the intervention group and 20 in the control group. Among the infants in the intervention group, there were 12 males (60%) and 8 females (40%). In the control group, there were 8 males (40%) and 12 females (60%). This gender distribution ensures diversity in examining the effects of music therapy on the occupational performance of preterm infants.

The inclusion criteria for participant selection involved infants with a corrected age of less than 2 months, a gestational age exceeding 36 weeks, parental consent, active participation in meetings with ward nurse approval, and the absence of critical health issues, including any acute medical conditions, such as respiratory distress syndrome, severe infections, or congenital anomalies that could preclude participation. The assessors, trained in evaluating infant performance, were responsible for administering assessments, while a qualified occupational therapist delivered the music therapy. Conversely, exclusion criteria included infant destabilization during the intervention, parental refusal to continue collaboration, and early discharge.

3.3. Randomization and Allocation

A stratified block randomization method (with concealed block size) was used to allocate participants to the intervention and control groups (31), with birth weight serving as the primary stratification factor to achieve a balanced distribution across groups. Initially, infants were categorized based on their birth weights into predefined strata, and random allocation was carried out using a block randomization algorithm to ensure equal distribution across the two groups within each weight stratum. The stratum-based randomization method aimed to maintain a balanced distribution of birth weights within the experimental and control groups, enhancing the robustness of the study's findings. The randomization sequence was generated by an independent researcher not involved in the intervention or assessment, and allocation was concealed in sequentially numbered, opaque envelopes opened only after enrollment.

To ensure methodological rigor, the randomization sequence was generated using a computer-based random number generator. Each envelope contained a single infant’s allocation code and was prepared by a researcher independent from data collection. The envelopes were identical and opaque to prevent any prediction of assignments. The sealed envelopes were opened by the study coordinator only after baseline assessments were completed, thus maintaining allocation concealment.

This stratified randomization strategy ensured a balanced distribution of participants according to birth weight between the intervention and control groups, minimizing selection bias and improving internal validity.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted following approval from the Iran University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (IR.IUMS.REC.1400.094) and registration with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20191109045380N1). Given the cultural context of Iranian NICUs, particular emphasis was placed on obtaining parental consent in a respectful and culturally appropriate manner.

Parents or legal guardians were approached by a trained member of the research team familiar with NICU routines and culturally sensitive communication practices. Study objectives, procedures, potential risks, and anticipated benefits were explained in simple, non-technical language. Parents were given adequate time to ask questions and to consult with spouses or extended family members if desired, reflecting common decision-making norms in Iranian families.

Participation was voluntary, and families were clearly informed that refusal would not affect the infant’s medical or nursing care. Consent discussions were held privately whenever possible, and postponed if parents appeared distressed, ensuring they were fully able to process the information. Written consent was obtained only after parents confirmed their understanding.

Confidentiality was ensured throughout, and all infants in both groups continued to receive standard NICU care.

3.5. Blinding

The outcome assessor was blinded to group assignment to minimize assessment bias. Due to the practical requirements of clinical care, the occupational therapist delivering the intervention and the NICU nursing staff assisting during sessions were necessarily aware of the allocation.

The families (parents or guardians) were not blind to the group assignment of their infants. Since the intervention involved a clear and observable activity (listening to music through headphones), parents who were present in the NICU could easily recognize whether their infant was receiving the musical intervention or not. Therefore, the parents of infants in the intervention group were aware that their child was receiving additional therapy, while parents of infants in the control group knew that their child was not receiving music therapy.

Although full blinding of parents was not feasible, measures were taken to minimize expectation bias. Parents were instructed not to alter their usual interactions or care routines during the study period, and all infants continued to receive identical nursing and medical care.

3.6. Sample Size Calculation

The sample size calculation, inspired by similar studies (32), ensured that each group comprised fewer than 20 individuals. The specific statistical parameters used in the calculation included a significance level (α) of 0.05, a power (β) of 0.80, standard deviations of the two groups (S₁ = 1.2 and S₂ = 1.5), and a difference in means (X̄₁ - X̄₂) of 2.0.

3.7. Procedure

Upon receiving ethical approval and the necessary authorizations from the Iran University of Medical Sciences, including the allocated IRCT code, an official introductory communication for the research dissertation was obtained from Akbarabadi Hospital, an esteemed affiliate of the university situated in Tehran. Informed consent forms were obtained from the parents or guardians of all participants before the intervention began, ensuring that they were fully aware of the study's aims, procedures, and potential risks. Following due permissions and with the concurrence of the departmental head, the sample selection was meticulously carried out, adhering to the predefined inclusion criteria of the study. The recruitment process commenced on May 22, 2021, and concluded on August 23, 2021. Participants were gradually enrolled, and assessments were performed on the same day.

A qualified occupational therapist, with two years of experience in infant care, administered a comprehensive suite of assessments, including a demographic information questionnaire (5 minutes), the TIMP (20 minutes), and the NBAS (60 minutes-observation). The assessments were performed on the same day, spaced throughout the day with rest periods to prevent fatigue. This timing was selected to accommodate developmental changes in infants and provide an accurate picture of their motor and behavioral status. The initial assessments were repeated after the completion of the ten intervention sessions to monitor any developmental changes that occurred as a result of the interventions.

The assessments were conducted by a qualified assessor, while the interventions were administered by a separate occupational therapist, who is also the primary researcher with a robust three-year proficiency in the specialized care of infants.

In contrast, the control group received conventional nursing, medical, and rehabilitative care. Rehabilitative measures included physical support, feeding assistance, and routine developmental monitoring (33). Excessive ambient noise in the NICU has been shown to affect infant development (34) and functioned as an uncontrolled environmental factor for both groups.

The intervention group underwent a supplementary regimen of music therapy consisting of ten sessions across six days, each lasting approximately 10 minutes. The music therapy protocol was developed based on established principles of neonatal auditory stimulation and evidence from previous research (35, 36), in accordance with the acoustic, rhythmic, and cultural parameters in Supplementary File. The selected compositions included Persian lullabies, Iranian folk music, and a custom composition emphasizing slow tempos (55 - 75 bpm), low-frequency tones (20 - 50 Hz), and minimal instrumentation. These features were selected for their demonstrated ability to support sensory-motor regulation and promote calm engagement in premature infants.

Music selections were chosen for their ability to support motor activity and behavioral regulation (37). The interventions occurred twice daily (except days 1 and 6), with approximately 4 hours between sessions. Each session followed a structured format:

1. Introductory piece to establish familiarity

2. Two movement-stimulating songs

3. A soothing concluding piece

Music was delivered through infant-safe headphones at 55 - 60 dB (38). Hygiene was ensured using disposable covers. Sound intensity was gradually increased and decreased at the beginning and end of each session. Musical piece attributes are presented in Supplementary File.

Infants’ physiological responses were monitored continuously. Sessions were paused if signs of distress occurred.

Although no formal pre-session alertness assessment tool was used, the clinical team conducted routine observational checks before each intervention to ensure infants were in an appropriate behavioral state (e.g., quiet awake or light sleep, not feeding, and not crying) in accordance with standard NICU practice. However, these observations were not quantified using a standardized tool, which is acknowledged as a limitation.

Parental involvement was minimal and limited to providing consent and demographic information. They were present during assessments when necessary but were not involved in administering the intervention.

Upon completion of the ten intervention sessions, infants were re-evaluated using the TIMP and the NBAS.

3.8. Data Collection Tools and Methods

The data collection process employed a carefully curated set of instruments to gain comprehensive insights into the demographics, motor performance, and behavioral patterns of the participating infants.

3.8.1. Demographic Information Questionnaire

This extensive questionnaire, collaboratively completed with caregivers, covered crucial demographic details, including the infant's name, gender, date of birth, corrected age, fetal age at birth, weight, delivery method, duration of hospitalization, and noteworthy health conditions, including orthopedic irregularities. It provided a holistic understanding of each infant's background and medical history.

3.8.2. Test of Infant Motor Performance

Tailored for infants from 32 fetal weeks to 16 weeks post-birth, the TIMP emerged as a key motor performance assessment tool. Conducted by occupational therapists and physiotherapists in specialized care and early intervention settings, it consisted of observational aspects, including 13 yes/no questions, and a stimulation component involving 29 questions scored from 0 to 4 or 5. The primary focus was the evaluation of postural control and motor game proficiency in infants. Demonstrating high levels of validity and reliability (ICC = 95%, 98%), the TIMP ensured consistent and robust evaluations (39). The Persian version exhibited high intra- and inter-rater reliability (ICC = 0.98, Kappa = 0.93), test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.98), and internal consistency (α = 0.82) (40).

3.8.3. Neonatal Behavioral Assessment Scale

Administered from 36 weeks of gestation to 2 months post-birth, the NBAS offered a comprehensive appraisal of newborn behavioral performance. Its components covered familiarization items (4 questions), social interaction (7 questions), movement system (5 questions), organization of situations (4 questions), regulation of situations (4 questions), autonomous system (3 questions), laughter (1 question), complementary items (7 questions), and reflex (18 questions). While exhibiting high validity, the NBAS demonstrated low to moderate reliability, a characteristic justified by the dynamic nature of infancy. The scoring spectrum varied across components, with scores ranging between 0 and 9 for most sections. The composite scoring involved averaging scores within each component (41).

3.9. Data Analysis Method

The data obtained from the study underwent thorough analysis utilizing SPSS version 23 software. The significance level for all statistical tests was set at P < 0.05. To assess the normal distribution of the data, the Shapiro-Wilk test was performed. Based on the distribution characteristics, several statistical tests were employed to assess the effectiveness of the intervention. The chosen analytical methods included:

- Wilcoxon signed rank test: This non-parametric test was applied to compare dependent samples, providing insights into the significance of changes within groups over time.

- Mann-Whitney test: As a non-parametric alternative to the independent samples test, the Mann-Whitney test was employed to compare distributions between the experimental and control groups, particularly suited for non-normally distributed data.

Missing data were handled using complete-case analysis. Any infant with missing post-intervention TIMP or NBAS scores was excluded from the corresponding analysis. No data imputation was performed due to the small sample size and non-parametric testing.

4. Results

The study included 40 infants, evenly divided between the intervention and control groups. Most infants (92.5%) were delivered by cesarean section, and Apgar scores at 1 and 2 minutes indicated generally stable neonatal status. Gestational age, head circumference, height, and birth weight were comparable between groups (Table 1).

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Boy | 25 (62.5) |

| Girl | 15 (37.5) |

| Delivery type | |

| Vaginal | 3 (7.5) |

| Cesarean | 37 (92.5) |

| Apgar 1 | |

| 4 | 2 (5) |

| 5 | 2 (5) |

| 6 | 1 (2.5) |

| 7 | 3 (7.5) |

| 8 | 6 (15) |

| 9 | 26 (65) |

| Apgar 2 | |

| 6 | 1 (2.5) |

| 7 | 2 (5) |

| 8 | 1 (2.5) |

| 9 | 6 (15) |

| 10 | 30 (75) |

| Week | |

| 28 | 2 (5) |

| 29 | 1 (2.5) |

| 31 | 2 (5) |

| 32 | 1 (2.5) |

| 34 | 1 (2.5) |

| 35 | 9 (22.5) |

| 36 | 24 (60) |

| Gestational Age (wk) | 34.8 ± 2.3 |

| Head Circumference (cm) | 32.8 ± 2.6 |

| Height (cm) | 44.6 ± 4.8 |

| Weight (g) | 2343.8 ± 657.8 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

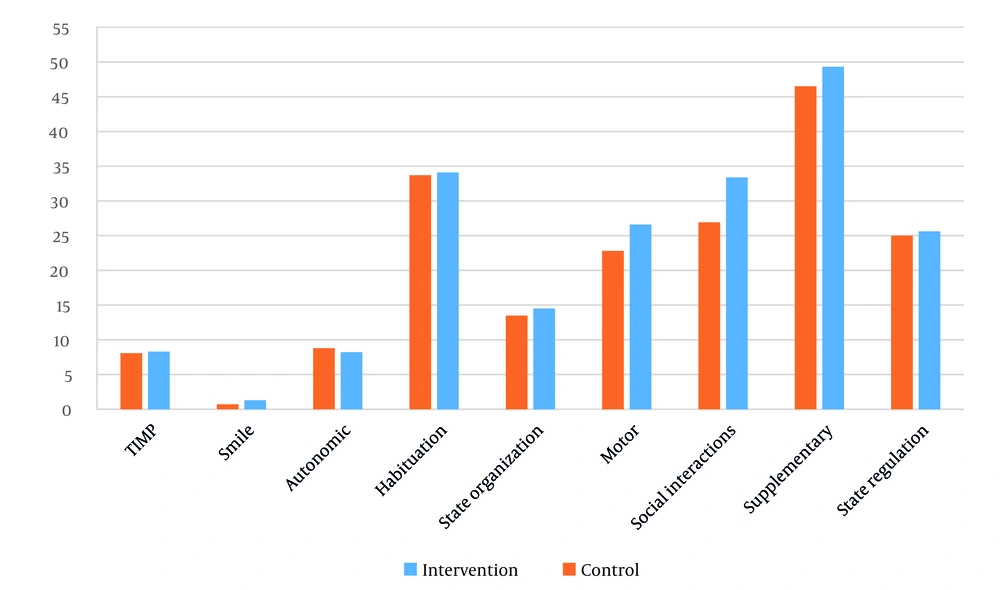

Table 2 shows that the intervention group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in state regulation, supplementary items, social interactions, habituation, and autonomic functioning compared with the control group. No significant between-group differences were found for motor performance, state organization, or infant smiling.

| Group | Pre-test | Post-test | Z-Score | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State regulation | -3.474 | 0.001 a | ||

| Control | 23.5 (4.3) | 25.0 (3.7) | ||

| Intervention | 22.0 (4.2) | 25.6 (3.3) | ||

| Supplementary | -3.197 | 0.001 a | ||

| Control | 44.8 (6.1) | 46.5 (6.4) | ||

| Intervention | 44.8 (5.5) | 49.3 (4.4) | ||

| Social interactions | -3.319 | 0.001 a | ||

| Control | 24.6 (5.6) | 26.9 (4.9) | ||

| Intervention | 29.1 (6.3) | 33.4 (5.8) | ||

| Motor | -0.792 | 0.429 | ||

| Control | 20.3 (4.2) | 22.8 (4.2) | ||

| Intervention | 23.8 (4.2) | 26.6 (2.9) | ||

| State organization | -0.069 | 0.945 | ||

| Control | 14.4 (5.1) | 13.5 (4.1) | ||

| Intervention | 14.9 (4.8) | 14.5 (4.1) | ||

| Habituation | -2.30 | 0.021 a | ||

| Control | 33.0 (3.1) | 33.7 (2.3) | ||

| Intervention | 32.7 (3.3) | 34.1 (2.8) | ||

| Autonomic | -2.792 | 0.005 a | ||

| Control | 8.6 (1.9) | 8.8 (1.6) | ||

| Intervention | 9.0 (1.6) | 8.2 (1.4) | ||

| Smile | -0.875 | 0.382 | ||

| Control | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.7) | ||

| Intervention | 1.0 (1.1) | 1.3 (1.1) |

a Indicates statistically significant results.

Table 3 summarizes within-group changes. The control group showed significant improvements in state regulation, state organization, social interactions, motor items, and supplementary items, while changes in habituation, autonomic system, and smile were non-significant.

| Variables | Control Group | Intervention Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-Score | P-Value | Z-Score | P-Value | |

| Habituation | -1.931 | 0.053 | -2.773 | 0.006 a |

| State regulation | -3.097 | 0.002 a | -3.316 | 0.001 a |

| Social interactions | -3.008 | 0.003 a | -3.432 | 0.001 a |

| State organization | -1.974 | 0.048 a | -0.884 | 0.377 |

| Motor | -3.243 | 0.001 a | -3.064 | 0.002 a |

| Autonomic | -0.940 | 0.347 | -2.085 | 0.037 a |

| Smile | -0.047 | 0.963 | -0.893 | 0.372 |

| Supplementary | -3.016 | 0.003 a | -3.435 | 0.001 a |

a Indicates statistically significant results.

In the intervention group, significant improvements occurred in habituation, state regulation, social interactions, autonomic system, motor items, and supplementary items, with non-significant changes in state organization and smile.

Together, these findings and Figure 1 illustrate that the intervention had selective benefits for behavioral regulation but did not produce measurable changes in motor performance.

5. Discussion

The objective of this study was to explore the impact of music therapy on the social communication, emotional regulation, and physiological responses of premature infants in the NICU. In the NICU, the maternal voice serves as a crucial tool for social communication and emotional and physiological regulation, particularly when physical proximity between parents and infants is restricted (42). This family-centered approach is cost-effective, as it reduces reliance on staff while utilizing the naturally available maternal voice (43). Unlike speech, which is less rhythmic, music provides structured auditory stimulation that supports infant engagement (44). The interactive nature of the intervention, as shown in studies by Malloch et al. (45) and Palazzi et al. (46), fosters positive social interaction in premature infants — an essential component of family-centered care for neurodevelopment (47). The use of recorded music and maternal voice recordings provides a sustainable, low-cost intervention that can be easily integrated into existing NICU routines (48).

Habituation, characterized by a reduced response to repeated stimuli, holds significance in infant learning and behavioral responses (49). Premature infants show weaker habituation to sensory stimuli, which may be worsened by ambient NICU noise (50, 51). Because excessive environmental noise is a well-documented stressor for premature infants, its presence in the NICU may have influenced several behavioral outcomes in the present study. High and unpredictable sound levels from alarms, equipment, conversations, and routine care activities can disrupt physiological stability, reduce the infant's ability to achieve organized behavioral states, and interfere with self-regulation (52). These effects may have increased variability in responses across both groups and may have partially masked the full potential impact of the music therapy on domains such as state regulation and autonomic stability. The inclusion of noise as an uncontrolled environmental factor is therefore important to consider when interpreting the magnitude and consistency of the observed effects. Given that both groups were exposed to the same high-noise NICU environment, it is also possible that uncontrolled background noise disproportionately affected the control group by increasing physiological stress and reducing opportunities for effective self-regulation. This may have widened the apparent difference between groups on NBAS domains related to autonomic stability and state organization. Conversely, the therapeutic music delivered to the intervention group may have acted as a buffering stimulus, partially counteracting the dysregulating influence of environmental noise, whereas the control group lacked such modulation. Therefore, some of the observed group differences may reflect not only the benefits of the intervention but also the adverse impact of NICU noise on infants who did not receive structured auditory support.

Consistent with Standley (53), the present study found that music facilitated habituation and regulated behavioral responses, suggesting its use as a soothing alternative when maternal voice or direct therapist involvement is unavailable.

The stability of state organization, a key characteristic of healthy infants (54), is influenced by non-conscious wakefulness. Infants displaying heightened non-conscious wakefulness exhibit less stability in state organization (55). Although the study did not aim to induce relaxation through music, it was not effective in controlling infant crying. Previous research on music's effect on infant crying, including studies by Gooding (56), Keith et al. (57), and Kemper et al. (58), has yielded varied results. State organization, encompassing infant excitability, is positively influenced by music, reducing arousal levels and promoting homeostasis. Persistent arousal from ambient noise hinders the transition from wakefulness to sleep, impacting sleep quality critical for neurodevelopment (59). Recorded music thus offers a practical, scalable intervention that can benefit multiple infants simultaneously while preserving individualized care (60).

Premature survivors often struggle with self-regulation, which is disrupted by stress and environmental overstimulation (61). Similar to Haslbeck (20), Haslbeck and Bassler (62), and Cevasco et al. (63), the present study suggests that music promotes self-regulation and stress reduction. Music’s influence on neural communication (64) and its impact on stress-related biomarkers (65) underscore its potential to enhance both immediate and long-term neurobehavioral outcomes.

However, the lack of significant improvement in motor performance, as reflected by non-significant TIMP results, requires careful interpretation. While behavioral domains such as state regulation and social interaction showed measurable enhancement, motor function improvements may not have reached statistical significance due to several factors. First, the short duration of intervention (six days) might have been insufficient to produce observable neuromotor changes, as motor development typically requires longer-term sensory-motor engagement. Second, the TIMP, although a validated measure, may lack sensitivity to detect subtle, short-term changes in infants’ spontaneous movement or postural control. Prior studies have reported similar findings (27, 53), noting that significant improvements in motor outcomes often emerge after extended intervention periods or when live, interactive music sessions are employed. This aligns with the present results, suggesting that the behavioral effects of music may precede measurable motor gains.

In interpreting these findings, it is also important to consider the measurement characteristics and inherent limitations of the TIMP and NBAS, particularly when used in short-duration intervention studies. The TIMP, although widely validated for assessing postural and motor control, is most responsive to developmental changes occurring over longer intervals, and its sensitivity to subtle, short-term neuromotor shifts is limited (66). Day-to-day physiological variability further influences TIMP performance, reducing its capacity to detect modest improvements arising from brief sensory-based interventions. Likewise, the NBAS demonstrates domain-specific differences in responsiveness. While domains such as autonomic stability, habituation, and state regulation respond relatively well to short-term auditory modulation, expressive and motor-related items including the smile and motor system scores require more mature neurobehavioral organization and show limited change during brief observation periods (67). These measurement properties help explain why certain behavioral domains improved while others did not, even when infants appeared to tolerate the intervention well.

According to the Synactive Theory of Development (68), self-regulation integrates movement, state control, and social interaction. Achieving this balance supports cardiorespiratory stability before discharge. Although medical equipment can restrict motor development (69), the present study suggests that music supports motor coordination, aligning with Provasi et al. (70). While some research has linked decreased movement with increased attention to music, the observed co-occurrence of heightened attention and movement in this study reflects a complex neurobehavioral response to auditory stimulation (29, 71).

The multidimensional nature of this intervention, combining gentle sensory and auditory stimulation, likely contributed to improved tolerance and alertness. These results are consistent with Standley (72), Nöcker-Ribaupierre (73), and Wood (74). Facilitating alert states through music supports early learning and cognitive engagement in preterm infants (75). Although no significant change was found in motor or smile scores, these findings highlight the nuanced timeline of developmental response to sensory input and emphasize the need for longer or repeated interventions to reveal full effects. Future research should explore extended intervention durations, larger samples, and longitudinal assessments to better capture delayed or cumulative motor benefits.

Even non-significant findings yield insights into developmental variability and guide refinement of future interventions. Recognizing that early behavioral regulation may serve as a foundation for later motor improvements strengthens the interpretation of partial findings as meaningful developmental progress rather than absence of effect.

Importantly, several NBAS domains showed significant improvement, particularly state regulation, social interaction, autonomic stability, and habituation. These areas may have been more sensitive to the rhythmic, low-frequency, and predictable auditory features of the intervention, which align closely with mechanisms known to support early behavioral regulation and sensory processing (76). The intervention targeted these domains indirectly by providing structured auditory input that reduces physiological stress, enhances orienting responses, and supports smoother transitions between behavioral states. This explains why domains such as state regulation and social interaction improved as expected under the initial hypothesis, which emphasized enhanced behavioral organization and emotional regulation. In contrast, domains like motor performance or smiling, which depend on longer developmental timelines and multimodal input, showed limited short-term responsiveness. Overall, the selective pattern of NBAS improvement supports the hypothesized benefits of music therapy on early behavioral regulation while clarifying that more extended or intensive interventions may be necessary to influence broader developmental domains.

In contrast to domains such as state regulation or habituation, infant smiling did not demonstrate measurable change, which is consistent with developmental expectations for this age group. Smiling in premature infants is largely reflexive and infrequent during the neonatal period and is highly dependent on physiological stability rather than external stimulation (77). Because premature infants often conserve energy for essential autonomic functions, expressive behaviors like smiling emerge later and show limited responsiveness to short-term sensory interventions. Additionally, previous work indicates that the NBAS smile item has relatively low sensitivity for detecting brief or subtle behavioral shifts in medically vulnerable infants (67). The duration and intensity of the music exposure in this study, which primarily targeted regulation and calming rather than social engagement, may also have been insufficient to influence early social behaviors that require more mature interactional capacities. Therefore, the absence of change in this domain likely reflects both normal developmental constraints and the measurement characteristics of the NBAS, rather than a lack of therapeutic potential.

Overall, the pattern of findings aligns with the study’s hypotheses in a domain-specific manner. Improvements in state regulation, autonomic stability, habituation, and social interaction support the hypothesis that music therapy enhances emotional and physiological regulation in premature infants. Conversely, the absence of significant improvement in TIMP motor performance indicates that the motor enhancement hypothesis was not supported within the brief intervention window, likely due to both developmental timing and instrument sensitivity. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the hypothesized benefits of music therapy were partially confirmed, predominantly in behavioral domains, while motor outcomes may require longer or more intensive intervention to manifest.

5.1. Implications for Occupational Therapy

Occupational therapy plays a crucial role in the rehabilitation and well-being of premature infants. Therapist training should combine theoretical knowledge with hands-on practice to address key developmental needs in this population. Programs must emphasize self-regulation, sensory processing, and family-centered care, with a focus on applying evidence-based interventions such as music therapy within the NICU setting.

Therapists should be trained to identify developmental delays and design individualized care plans that address specific infant needs, including their ability to engage in meaningful occupations.

Training programs should also focus on promoting infant participation in activities that enhance physiological, emotional, and social development. These activities can improve infants’ overall quality of life while reducing caregiver stress. Education should combine structured coursework with in-unit mentorship, ensuring that therapists are equipped to apply interventions effectively within real clinical settings.

Furthermore, OT education should prioritize family engagement, helping parents understand their infant’s developmental needs and empowering them to contribute meaningfully to care routines.

Beyond the NICU, occupational therapists can guide families in incorporating simple, developmentally appropriate sensory activities at home, such as gentle rocking, skin-to-skin contact when possible, visually engaging toys with soft lighting, and predictable daily routines that support regulation. Therapists can also teach parents how to use calming auditory strategies, including recorded maternal voice, soft rhythmic humming, or culturally familiar lullabies, to promote smoother state transitions and support emerging self-regulation.

Therapists can specifically target state regulation through structured auditory interventions such as individualized music selections, recorded parental voices, or soft rhythmic patterns designed to stabilize arousal and help infants maintain quiet alert states that support learning. These strategies can be practiced during therapy sessions and taught to parents for use during feeding, sleep routines, and soothing times.

Recognizing that many families face barriers to frequent NICU presence, occupational therapists can support engagement by providing written or recorded guidance, scheduled virtual consultations, or brief training sessions during visiting hours. They can also help caregivers participate indirectly by recording their voices, reading short stories, or singing lullabies to be played for the infant during times when parents cannot be physically present. Such approaches help ensure that all families, including those with work constraints or geographic limitations, remain active contributors to their infant’s developmental care.

By fostering early engagement in sensory-motor play, improving sucking ability, and supporting social participation, occupational therapists can make a substantial impact on developmental outcomes for premature infants. These approaches not only strengthen immediate functional abilities but also support long-term participation and family well-being.

In summary, occupational therapists are uniquely positioned to bridge the gap between medical care and developmental support in the NICU. Through the integration of music and sensory-based interventions, therapists can promote both infant recovery and parental confidence.

5.2. Limitations

This study faced several limitations. Controlling for factors such as family history, genetic predispositions, and medication effects was challenging, potentially influencing outcomes. The short-term design without post-discharge follow-up limited insights into long-term benefits. Future longitudinal studies are needed to confirm sustained effects. Additionally, focusing on relatively mature preterm infants limits the generalizability to critically ill infants; tailoring interventions based on health status could be more effective. Measurement tools used, particularly the binary movement questionnaire, may have lacked sensitivity, potentially missing subtle changes. Additionally, infant behavioral state (alertness/sleep readiness) was not formally scored before each session. Although routine clinical observations were used to confirm infant stability prior to intervention, the absence of a standardized behavioral state tool limits precision in determining whether intervention timing aligned with optimal infant readiness. Another limitation was the use of non-parametric statistical methods due to the small sample size and non-normal data distribution; while appropriate for this dataset, such methods restrict advanced comparative analysis. Future research could benefit from interval-scaled measures for more nuanced assessments and larger samples that allow for robust statistical models such as ANCOVA or mixed-effects analysis.

5.3. Recommendations and Offers

The findings suggest several strategies for clinical practice and research. Training parents to address psychological trauma can enhance parent-infant attachment, reduce stress, and support infant development. Encouraging family participation in the NICU, using recorded music with coaching, could be a cost-effective way to improve bonding and developmental outcomes. Structured discharge and follow-up plans with interdisciplinary collaboration are also recommended to support ongoing development. Enhancing occupational therapists’ NICU-specific skills would improve their capacity to address complex challenges affecting infant and parent performance.

Future research should also incorporate validated pre-intervention state assessments (e.g., alertness or sleepiness scales) to improve accuracy and interpretability of outcomes, ensuring that music is administered at developmentally appropriate times.

Finally, future studies should expand to include infants experiencing higher stress or environmental deprivation to optimize intervention strategies for neurodevelopmental support. It is also recommended that future studies employ larger samples and more advanced statistical approaches, such as ANCOVA, to better control for covariates and strengthen interpretation of between-group differences, particularly in motor performance outcomes.

5.4. Conclusion

This study highlights the potential of music interventions in neonatal care for premature infants, with significant effects observed in areas such as state regulation, social interactions, and autonomic system responses. However, the intervention did not produce significant improvements in motor performance as measured by the TIMP, indicating that short-term musical exposure may influence behavioral regulation more readily than neuromotor development. These findings suggest that music’s impact may vary by developmental domain, with behavioral responsiveness showing earlier change than motor control.

Despite these mixed results, music interventions, particularly recorded music and maternal voice recordings, offer a cost-effective, easily implemented tool in neonatal care. Nevertheless, conclusions regarding motor outcomes should be interpreted cautiously due to the limited duration of the intervention, the small sample size, and the potential insensitivity of short-term motor assessments. Further research is needed to refine intervention strategies, explore long-term effects, and assess the role of family involvement in enhancing outcomes.

Overall, while the present study supports music therapy as a promising adjunct for improving behavioral regulation, its role in motor development remains inconclusive and warrants more rigorous investigation.