1. Background

Sensory profiles are essential for understanding individual differences in sensory processing. These differences shape how individuals interact with their environment and respond to therapeutic interventions, counseling, and occupational demands (1, 2). The Sensory Profile Questionnaire is a globally recognized, standardized tool for assessing these sensory processing patterns (3). However, its cultural and linguistic adaptation, coupled with psychometric validation, is crucial to ensure reliability and contextual relevance across diverse populations (4-7).

Originally developed by Dunn in 1999, the Adult Sensory Profile contains 39 items distributed across four domains: Sensory seeking, sensory avoiding, sensory sensitivity, and low registration (8). These domains, which span multiple sensory modalities, are rated on a five-point Likert scale. Each domain consists of 15 items, yielding total scores ranging from 15 to 75 (3). Although the tool was initially designed for children (9, 10), it has since been adapted for older age groups as the significance of sensory processing in daily functioning and quality of life has become increasingly evident (11)

In adults, sensory processing disorders — manifesting as hyper- or hyposensitivity — can adversely affect cognitive, emotional, and social functioning. This often leads to anxiety, reduced attention, and impaired interpersonal relationships (12, 13). Accurate assessment using validated instruments is therefore essential, as it facilitates targeted interventions and informs the development of effective rehabilitation strategies aimed at improving quality of life.

The Sensory Profile Questionnaire has been translated and validated in numerous countries, including Turkey (13), Spain (14), China (15), and Saudi Arabia (16). This global application underscores the critical role of cultural factors, as they significantly influence response patterns and the expression of both adaptive and maladaptive behaviors across different populations. Consequently, to ensure linguistic and cultural appropriateness, the preferred approach is often to adapt and validate existing well-established tools rather than develop new ones from scratch.

The Sensory Profile stands out among sensory assessment tools due to its strong standardization, user-friendly design, wide age-range applicability, and ability to monitor changes in sensory processing over time. In contrast, other instruments often face challenges such as complexity, limited validation, and difficulties in interpretation. When properly adapted to cultural and demographic contexts, this tool provides accurate and comprehensive data, enabling researchers and clinicians to assess sensory processing with greater precision and reliability. Its applications extend beyond academic research, making it invaluable for developing targeted interventions and advancing sensory science.

In Iran, the lack of a culturally adapted sensory assessment tool for adults poses a significant barrier to accurate evaluation. Although imported psychometric tools are increasingly used in mental health and social science fields, many are applied without rigorous validation for the local population. This practice increases the risk of misinterpretation and compromises data quality. This study aims to adapt the Adult Sensory Profile culturally and linguistically for healthy Iranian adults and evaluate its psychometric properties, including validity and reliability. The results will provide a scientific basis for the tool’s use in clinical and research settings in Iran and contribute to standardizing sensory assessment for this population. Given the importance of sensory processing in daily functioning and its relevance to fields such as occupational therapy, obtaining validated psychometric data for Iranian adults is both timely and essential.

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties — including face, content, concurrent validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability — of the Sensory Profile Questionnaire in healthy Iranian adults. While previous research in Iran has validated this tool for children (9, 10) and elderly individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (17), no study has yet examined its properties in the general adult population. This research specifically focuses on adults aged 20 - 26, a developmental period marked by stabilized sensory processing patterns and minimal confounding factors such as age-related decline or medical conditions. The absence of major neurological or psychiatric disorders in this age group also allows for the collection of reliable normative data. Selecting this homogeneous cohort enhances result precision, reduces bias, and supports future comparability, addressing a significant gap in the validation of sensory assessment tools for healthy Iranian adults.

3. Methods

This research employed a descriptive cross-sectional study design.

3.1. Research Population

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted among the accessible population of students enrolled at Semnan University of Medical Sciences and Health Services in Semnan city during the academic year of 1401. Participants were selected based on the study's predefined inclusion criteria. The required sample size was estimated to be 166 participants using the standard formula for estimating a population proportion: N = (Z2 × P × q)/d2, where:

- Z = 1.96 (corresponding to a 95% confidence level).

- P = 0.4 (estimated proportion).

- q = 0.6 (1 - P).

- d = 0.05 (desired margin of error).

This calculation assumed a test power of 0.80. Furthermore, to assess test-retest reliability, a subsample of 40 participants (approximately 10% of the total calculated sample) was included (18). Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) Age between 20 and 26 years, (2) a score above 21 on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and (3) an absence of self-reported major medical or psychological conditions. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Failure to complete the Adult Sensory Profile Questionnaire in full, (2) voluntary withdrawal from the study at any stage, and (3) insufficient cooperation during the assessment process.

3.2. Study Design

The research procedure was conducted as follows: After obtaining the necessary ethical approval from the Ethics Committee in Biological Research at Semnan University of Medical Sciences (approval number: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1402.011), eligible participants who met the inclusion criteria were provided with a detailed explanation of the study. All participants subsequently read and signed an informed consent form. Participants then completed a Personal Information Questionnaire — capturing demographic and background variables such as age, gender, educational level, income, and medical history — followed by the Adult Sensory Profile Questionnaire.

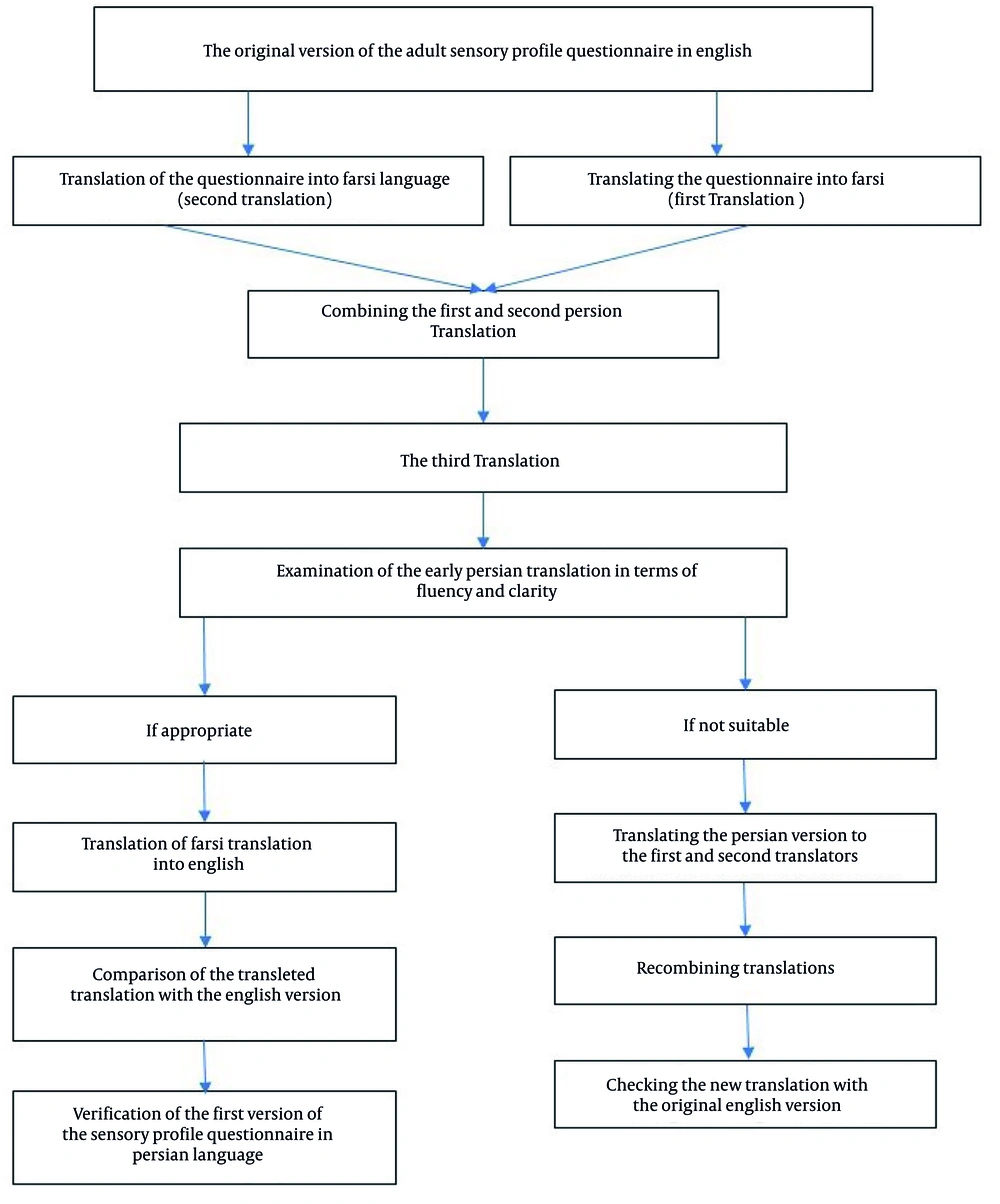

The process of implementing the research and adapting the questionnaire adhered to the World Health Organization (WHO)'s guidelines for the cross-cultural adaptation of instruments (15). This comprehensive process encompassed four key stages:

1. Translation: Independent double back-translation (forward and backward translation).

2. Content validity assessment: Evaluation of the translated questionnaire's content validity by consulting an expert panel.

3. Reliability assessment: Determination of the instrument's internal consistency.

4. Stability assessment: Evaluation of test-retest reproducibility.

3.3. Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 20. The normality of the score distributions was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances was examined using Levene's test. The significance level for all statistical analyses was set at P < 0.05. The data analysis corresponded to the four stages of the cultural adaptation and validation process:

1. Face validity: The face validity of the Persian version of the Adult Sensory Profile was established through the independent double back-translation method.

2. Content validity: Content validity was determined by calculating the Content Validity Index (CVI) based on expert panel evaluations. Concurrent validity was assessed by calculating Pearson's correlation coefficient between the questionnaire scores and those of the Adult Sensory Processing Questionnaire (ASPQ).

3. Internal consistency: The internal reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated using Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's omega coefficients. Criterion validity for each subscale was further examined by calculating its correlation with the total score of the questionnaire.

4. Test-retest reliability: The stability of the questionnaire over time was measured using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) or Pearson's correlation coefficient for test-retest reliability.

3.3.1. First Stage: Translation

To assess face validity, the independent double back-translation method was used (19). Four translators collaborated in this process: Two independently translated the questionnaire from English to Persian, then two others merged these into a single version. An expert panel of three occupational therapists and four translators reviewed and refined the translation. The Persian version was then back-translated to English by two separate translators, and the resulting English version was compared and finalized against the original.

3.3.2. Second Stage: Content Validity and Concurrent Validity

To evaluate concurrent validity, a panel of experts in neuroscience and sensory processing was assembled based on predefined criteria (PhD in relevant fields; ≥ 5 years of adult practice experience). Following Yusoff (20), five occupational therapy faculty experts evaluated the Persian questionnaire using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = irrelevant to 4 = highly relevant) across four domains: Relevance, clarity, simplicity, and terminology ambiguity. After incorporating expert feedback, ten participants further assessed these domains. The CVI was calculated as the proportion of experts rating items ≥ 3. The final version integrated all expert and participant feedback. The translation process is summarized in Figure 1.

3.3.3. Concurrent Validity

To evaluate concurrent validity, the ASPQ was employed as an external criterion. The ASPQ assesses sensory processing patterns in adults across key modalities — auditory, visual, tactile, and proprioceptive — and has demonstrated strong psychometric properties and cross-population applicability (4). Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated between the Adult Sensory Profile and ASPQ scores to determine concurrent validity (4).

3.3.4. Internal Consistency

In the third stage, internal consistency was evaluated by administering the questionnaire to all participants and instructing them to respond attentively to each item. Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients to determine the consistency of responses across items and subscales.

3.3.5. Test-Retest Reliability

To evaluate test-retest reliability, the questionnaire was administered to a subset of 40 participants on two separate occasions, with a 14-day interval between administrations. Pearson’s correlation coefficient and the ICC were used to assess the consistency and agreement of scores over time.

4. Results

In this study, 166 participants (127 women and 39 men) with a mean ± standard deviation age of 22.093 ± 7.211 years participated (Table 1). The results of this study indicated that the data were normally distributed.

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 127 (76.5) |

| Men | 39 (23.5) |

| Total number | 166 (100) |

| Age (y) | |

| Female | 22.845 ± 6.550 |

| Men | 21.341 ± 7.873 |

| Total number | 22.093 ± 7.211 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

The content validation of the Persian version of the Adult Sensory Profile was conducted in a two-stage process. In the first stage, five doctoral-level occupational therapy experts evaluated the relevance and clarity of each item. The experts had a mean ± standard deviation age of 38.2 ± 5.069 years and an average of 13.60 ± 2.509 years of professional experience. All items were unanimously endorsed as appropriate, and each achieved a CVI exceeding the recommended threshold (CVI > 0.99), demonstrating excellent content validity. Although the high consistency across items initially supported reporting only the overall CVI, item-level CVI and Content Validity Ratio (CVR) values are provided in Table 2 for greater transparency.

| Items | CVI | CVR |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 3 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 4 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 8 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 9 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 10 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 11 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 12 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 13 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 14 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 15 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 16 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 17 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 18 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 19 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 20 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 21 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 22 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 23 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 24 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 25 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 26 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 27 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 28 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 29 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 30 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 31 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 32 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 33 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 34 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 35 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 36 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 37 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 38 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 39 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 40 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 41 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 42 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 43 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 44 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 45 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 46 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 47 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 48 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 49 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 50 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 51 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 52 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 53 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 54 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 55 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 56 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 57 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 58 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 59 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 60 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Abbreviations: CVI, Content Validity Index; CVR, content validity ratio.

In the second phase, face validity was evaluated with a sample of 10 adult participants (mean ± standard deviation age = 21.60 ± 0.966 years). Most participants reported that the items were clear and comprehensible; however, several were identified as linguistically ambiguous and were subsequently refined to improve clarity. Examples of modifications include:

- Item 11: Changed from “Sense of movement in escalators and elevators” to “Riding escalators and elevators and sensing their movement.”

- Item 12: “Objects” was replaced with “Items”.

- Item 15: “Discomfort” was revised to “Insecurity”.

- Item 20: “Nervous” was substituted with “Frustrated”.

- Item 25: “Carnival” was replaced with “Demonstration”.

These adjustments were made exclusively to enhance linguistic precision and did not modify the conceptual foundation of the instrument. The final Persian version preserved all original items and remained conceptually consistent with the Source Questionnaire.

4.1. Internal Consistency

To assess internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients were computed for each subscale and the total score. Standard errors (SE) were also derived to evaluate the precision of the reliability estimates. The results are summarized in Table 3.

| Factors | SE | Cronbach's Alpha | Macdonald's Omega Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensory registration | 0.032 | 0.744 | 0.751 |

| Sensory seeking | 0.028 | 0.761 | 0.756 |

| Sensory avoidance | 0.035 | 0.721 | 0.747 |

| Sensory sensitivity | 0.030 | 0.735 | 0.712 |

| Total score | 0.026 | 0.740 | 0.742 |

Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

Both Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega values exceeded 0.70 for all subscales and the total score, indicating satisfactory internal consistency. As a more robust estimator for multidimensional constructs, omega yielded results consistent with those of alpha. The low SE further affirmed the precision and stability of these reliability estimates. Among the subscales, sensory seeking demonstrated the highest internal consistency, while sensory avoidance showed the lowest — a pattern that may reflect inherent individual differences in the processing of avoidant sensory stimuli.

4.2. Validity

Criterion validity was examined by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients between each subscale and the total score of the Adult Sensory Profile. Confidence intervals (95%) were also reported to evaluate the strength and precision of these associations. The results indicated robust and statistically significant correlations across all subscales.

Based on the results presented in Table 4, strong correlations were observed between the total score and the sensory seeking, sensory sensitivity, and sensory avoidance subscales, indicating good criterion validity. Although the correlation for the low registration subscale was somewhat lower, it remained within an acceptable range, supporting the relevance of all subscales to the overall construct.

| Subscales | The Total Score of the Sensory Profile Questionnaire | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson Correlation Coefficient | 95% Confidence Interval | P-Value | |

| Sensory registration | 0.807 | 0.76 - 0.84 | < 0.001 |

| Sensory seeking | 0.847 | 0.81 - 0.88 | < 0.001 |

| Sensory avoidance | 0.722 | 0.68 - 0.76 | < 0.001 |

| Sensory sensitivity | 0.791 | 0.75 - 0.83 | < 0.001 |

4.3. Test-Retest Reliability

To evaluate temporal stability, a test-retest analysis was conducted with a two-week interval in a sample of 40 participants. Both Pearson’s correlation coefficient and the ICC were calculated to ensure a comprehensive assessment of reliability. The results were as follows:

- Pearson’s R = 0.743 (95% CI: 0.68 - 0.81), indicating acceptable linear consistency.

- The ICC (two-way mixed model, absolute agreement) = 0.765 (95% CI: 0.70 - 0.83), reflecting good agreement and temporal stability.

While Pearson’s R captures the strength of the linear relationship between test and retest scores, the ICC provides a more rigorous measure by accounting for both systematic and random errors, thereby offering a fuller picture of reliability. The obtained ICC value confirms that the Adult Sensory Profile exhibits good stability over time in healthy adults. All analyses adhered to the International Test Commission (ITC) guidelines (19) and the American Psychological Association’s AERA standards (21).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to culturally adapt and evaluate the psychometric properties of the Adult Sensory Profile for use with healthy Iranian adults. The resulting Persian version provides a valuable tool for clinicians and therapists working with Persian-speaking populations, enabling them to monitor sensory changes, assess test-retest reliability, and evaluate sensory adaptation. The translation methodology aligns with established cross-cultural adaptation approaches, such as those employed by Png et al. in Malaysia and Gandara-Gafo et al. in Spain (4, 15). The CVI obtained in this study (> 0.99) is consistent with the results reported by Png et al. (15), underscoring the robustness of item relevance across cultural settings. Similarly, studies by Zaree et al. (17) and Shahbazi et al. (10) confirmed the appropriateness of all items, further validating the questionnaire’s comprehensive coverage of sensory processing domains.

Additionally, this study demonstrated good internal consistency across all subscales of the Adult Sensory Profile — low registration, sensory seeking, sensory sensitivity, and sensory avoidance. These results align with previous validations of the instrument in other cultural contexts, including the Malaysian (15), Greek (22), and Turkish (13) versions. The strong internal consistency may be attributed to high inter-item correlations and their alignment with the total score, supporting the reliability of the adapted tool.

In this study, the sensory seeking subscale demonstrated the strongest correlation with the total score, whereas the sensory avoidance subscale exhibited the weakest. These findings align with those of Png et al., who similarly reported the highest correlation (R = 0.84) within the sensory seeking domain. This pattern may reflect a natural inclination among adults to actively seek out varied sensory stimuli and novel experiences, thereby enhancing engagement in sensory-seeking behaviors. Previous research suggests that positive sensory encounters may reinforce motivational mechanisms underlying sensory exploration, contributing to higher activity levels and stronger inter-item consistency within this subscale (15).

Conversely, the relatively lower correlation observed in the sensory avoidance subscale may be attributed to environmental variability and individual differences in sensitivity to specific sensory inputs. In certain individuals, neurological predispositions may favor withdrawal from sensory stimulation, resulting in avoidance behaviors that operate somewhat independently of other sensory processing patterns. This is consistent with reports by Zaree et al., who noted significant differences in sensory avoidance and low registration between healthy older adults and those diagnosed with dementia (17). Similarly, Png et al. observed that sensory registration (likely referring to low registration) showed the lowest correlation (R = 0.75) with the total score in their sample (15)

To evaluate the temporal stability of the Adult Sensory Profile, a test-retest analysis was performed using Pearson’s correlation. The results demonstrated satisfactory reliability over time (R = 0.743), confirming the instrument’s consistency in measuring sensory processing traits. These findings are consistent with earlier Persian validations by Zaree et al. (17) and Shahbazi et al. (10), as well as with international adaptations such as those by Chung (23) and Ucgul et al. (13), supporting the tool’s cross-cultural reliability.

The high test-retest correlation suggests that sensory processing traits in adults remain relatively stable over time and that the questionnaire’s standardized structure elicits consistent responses across repeated administrations. This reinforces the robustness of the Adult Sensory Profile in capturing enduring sensory characteristics. The authors conclude that the instrument is well-suited for the precise and reliable assessment of sensory processing across multiple dimensions in healthy adults (10, 17, 24, 25)

Moreover, this version of the questionnaire overcomes limitations of earlier Persian adaptations, which were designed for specific populations such as children or individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. By focusing on sensory experiences relevant to daily life and social functioning, the current instrument offers improved applicability for the general adult population and enhances the clinical and research utility of sensory assessment in Persian-speaking contexts.

A key strength of this study is its careful semantic and cultural adaptation of the Adult Sensory Profile. The translation prioritized natural expression and accessibility, avoiding literal phrasing to ensure comprehensibility across diverse cognitive and educational backgrounds. A multi-step expert review further refined the instrument, resulting in a linguistically accurate and culturally appropriate tool. Rigorous psychometric validation — including assessments of concurrent validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability — confirmed the tool’s precision and reliability for use with Persian-speaking adults.

However, the study had several limitations, including incomplete participant responses that required additional sampling and increased resource use. The absence of inter-rater and intra-rater reliability assessments, as well as factor analysis, restricted deeper insights into measurement consistency and structural dimensions. Despite these limitations, the study successfully evaluated core psychometric properties and optimized the tool for the target population.

Future research should improve participant engagement to reduce attrition, incorporate inter-rater and intra-rater reliability evaluations, and perform factor analysis to further validate the questionnaire’s structural framework. These steps would contribute to developing a more comprehensive and psychometrically robust sensory assessment tool for Persian-speaking adults.

5.1. Conclusions

The findings demonstrate that the Persian version of the Adult Sensory Profile shows satisfactory validity and reliability, supporting its use in both clinical and research settings. This instrument enables Persian-speaking clinicians and researchers to identify sensory processing patterns, assess sensory functioning, and better address the needs of individuals with sensory challenges. It can also inform rehabilitation planning, monitor therapeutic progress, and track sensory changes over time.

Future studies should investigate the questionnaire's factorial structure and conduct more advanced psychometric analyses. Additional validation across diverse cultural subgroups would enhance its generalizability and clinical utility, contributing to the development of more refined sensory assessment tools.