1. Background

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most prevalent form of oral cancer, accounting for over 90% of oral malignancies and affecting approximately 377,000 individuals annually worldwide (1, 2). Despite advances in therapy, OSCC continues to carry a poor prognosis, with a global 5-year survival rate of less than 50%, primarily due to late-stage diagnosis and high recurrence rates. Survival is strongly stage-dependent: Early-stage OSCC (stage I) has a 5-year survival rate exceeding 80%, whereas advanced-stage disease (stage IV) often falls below 20% (1-4). It often arises from precancerous lesions, including oral lichen planus (OLP), a chronic inflammatory condition that affects about 0.5% to 2.6% of adults globally (3-6). Although the precise etiology of OLP remains unclear, immune-mediated mechanisms are thought to play a key role (3, 4, 7, 8). Since the first documented case in 1910 linking OLP to malignant transformation, subsequent studies have indicated that erosive and atrophic forms of OLP may carry a risk of progression to OSCC, with transformation rates reported between 0.5% and 10%, depending on follow-up duration (3, 9, 10).

Recent advances have explored innovative treatments such as topical palifermin and tacrolimus for early management of oral mucositis and ulcers. Palifermin, as an epithelial growth factor analog, has shown promise in reducing mucosal damage during cancer therapy (11). Tacrolimus, an immunosuppressant, has been effective in treating inflammatory oral conditions, further supporting its utility in oral mucosa-related disorders (12). Although these treatments target inflammation or tissue repair, there remains a need for reliable molecular markers to assess malignancy risk in oral potentially malignant disorders such as OLP.

Genetic alterations in oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and DNA repair genes significantly contribute to cancer development, including OSCC (13-19). MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression by inhibiting translation or promoting the degradation of target mRNAs. These molecules are involved in regulating critical cellular processes such as growth, differentiation, and proliferation, making them key players in cancer biology. Depending on their specific roles, miRNAs can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors (17, 20-24).

While extensive research has established the involvement of miRNAs in various cancers, comparative studies focusing on their role in OLP and OSCC are relatively limited (17, 20-25). Among these, miRNA 146a has emerged as a candidate due to its regulatory role in immune responses and oncogenic pathways (8, 26, 27).

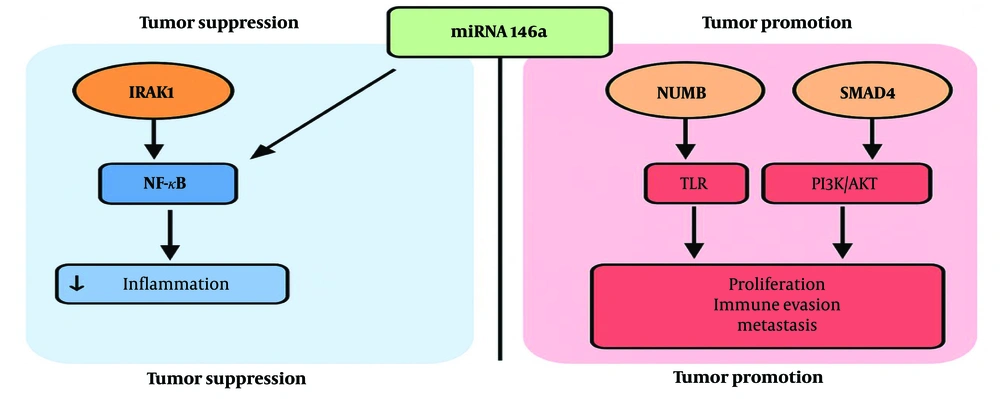

The miRNA 146a is biologically significant because of its dual regulatory function (Figure 1). It is involved in inflammation-driven carcinogenesis via NF-κB signaling, PI3K/AKT, and Toll-like receptor (TLR) pathways, and it modulates mediators such as interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1) and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) (28-30). Several studies have reported elevated miRNA 146a expression in OSCC compared to premalignant and normal tissues, suggesting its potential as a discriminatory marker (31). Unlike other oncogenic miRNAs, such as miR-21 and miR-31, which primarily promote proliferation and invasion, miRNA 146a also impacts immune regulatory networks, making it a relevant target for mechanistic exploration (29, 31).

However, due to the complexity of miRNA interactions and redundancy in regulatory pathways, reliance on a single marker limits interpretability. A more robust understanding may eventually require multi-marker profiling. Nevertheless, evaluating miRNA 146a as an individual marker may provide foundational insight into its relevance in OLP and OSCC. There is a clinical need for molecular markers that can distinguish benign inflammatory lesions from malignant neoplasms. Identifying such markers may help stratify OLP cases by transformation risk and guide clinical management. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine miRNA 146a expression specifically in erosive OLP and well-differentiated OSCC using samples from an Iranian patient cohort. This novel regional analysis contributes new population-specific insight into a biomarker with established roles in oral inflammation and carcinogenesis.

2. Objectives

This study aims to compare the expression levels of miRNA 146a in OLP and OSCC tissue samples to assess its potential utility as a molecular discriminator between benign and malignant oral lesions.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Sample Selection

This retrospective, cross-sectional study included 30 OSCC and 18 OLP formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples. All specimens were obtained from the pathology archive of the Cancer Institute of Imam Khomeini Hospital, Tehran, Iran, and were collected from Iranian patients who underwent surgery between 2018 and 2021. The sample size reflects the availability of qualified specimens within the archival collection that met the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. Given the limited availability of archived, high-quality, histologically confirmed samples, the groups were unequally distributed (30 OSCC vs. 18 OLP). Only cases meeting strict inclusion criteria (erosive OLP and well-differentiated OSCC with sufficient RNA integrity) were selected. This unbalanced sample size reflects the constraints of retrospective archival availability and not biological or analytical preference. Future prospective studies should aim to recruit balanced cohorts based on power analysis.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria for OLP cases were a clinical diagnosis of erosive OLP and histopathological confirmation according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, with explicit exclusion of epithelial dysplasia. The OSCC cases were included only if they were confirmed as well-differentiated. Cases with insufficient tissue or poor RNA quality were excluded. All slides were independently reviewed by two experienced oral pathologists to confirm the diagnosis of erosive OLP and to exclude epithelial dysplasia. Dysplasia was assessed according to the WHO histopathological criteria, and only cases with complete consensus between reviewers regarding the absence of dysplasia were included.

Normal mucosa was used only during qPCR assay validation and was not included in the statistical analysis due to the limited availability of matched healthy tissue samples with sufficient RNA integrity. The absence of a healthy control group is acknowledged as a limitation, as it restricts the scope for comparative interpretation of baseline miRNA 146a expression levels. Future studies should aim to incorporate healthy oral mucosal tissues to establish more robust baseline reference values.

3.3. Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IAU.DENTAL.REC.1398.071). For the retrospective use of archival FFPE tissue samples, informed consent was waived by the committee in accordance with institutional and national ethical guidelines.

3.4. RNA Extraction

The target RNA was extracted from the tissue samples using the RiboEX RNA extraction kit (Genall, South Korea). Initially, a piece of tissue weighing between 50 - 100 mg was excised, finely minced with a sterile bistoury on sterile foil, and placed into a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube. For homogenization, 1 mL of RiboEX solution was added to the tube to lyse the cells, which was then inverted multiple times and vortexed 2 - 3 times until no visible tissue mass remained. To separate RNA from DNA and proteins, 200 µL of chloroform was added, the mixture was inverted 2 - 3 times, and centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4°C for 15 minutes, resulting in three distinct phases: RNA in the upper aqueous phase, DNA in the interphase, and proteins in the lower organic phase. The upper RNA-containing layer was carefully transferred to a new tube, and 400 µL of cold isopropanol was added to precipitate the RNA, which was then stored at -20°C for at least 12 hours. Following incubation at room temperature for 10 minutes, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 g at 4°C for 4 minutes to form a white RNA pellet. The pellet was washed twice with 1 mL of 75% ethanol, centrifuging at 7500 g at 4°C for 5 minutes each time, to remove any residual impurities, such as salts. After the final wash, the ethanol was carefully removed, and the pellet was air-dried for at least 5 minutes, ensuring not to over-dry it to maintain solubility. Finally, the RNA pellet was resuspended in 50 µL of DEPC-treated water to achieve a homogenous RNA solution.

3.5. Quantitative and Qualitative RNA Evaluation

The concentration and purity of the extracted RNA were assessed using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, UK). Absorbance ratios of 260/280 and 230/260 nm were measured, with acceptable purity ranges being 1.8 - 2.2 and 1.7 - 1.9, respectively. RNA integrity was assessed by visual inspection of 28S/18S band resolution on agarose gel electrophoresis, as RIN values could not be obtained due to the fragmented nature of RNA from FFPE samples and the lack of a Bioanalyzer. Instead, purity ratios (A260/280 and A230/260) and electrophoretic banding patterns were used to confirm acceptable RNA quality for downstream qPCR analysis.

3.6. The cDNA Synthesis

The cDNA synthesis was performed using the THERMO kit. After quantifying the RNA with the Nanodrop device, all RNA samples were normalized to a concentration of 1000 ng/µL. A reaction mix containing RNA, water, oligo, and random primers was incubated at 65°C for 5 minutes, followed by cooling on ice. After adding 10 µL of RT Master Mix enzyme, the reaction proceeded as follows: 25°C for 10 minutes (primer binding), 42°C for 60 minutes (cDNA synthesis), and 70°C for 10 minutes (enzyme inactivation).

3.7. The cDNA Quality Control

To validate cDNA synthesis and RNA quality, real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was conducted using ACTB and GAPDH control primers. ACTB was chosen as the reference gene due to its consistent and stable amplification across all samples, as verified by melt curve analysis and gel electrophoresis. The specificity of ACTB amplification was confirmed by a single sharp peak in the melt curve and a single band of expected size on the agarose gel, indicating the absence of non-specific products or primer dimers. A master mix containing nuclease-free water, template cDNA, and Master Mix PCR Amplicon was prepared. Each reaction received 19 µL of this mix along with 0.5 µL of each forward and reverse primer. The samples were then placed in a PCR device according to the protocol given in Table 1. Post-reaction, samples were analyzed on 1.5% agarose gel to confirm product specificity.

| Protocol; Steps | (°C) | Time | No. of Cycles |

|---|---|---|---|

| cDNA control | |||

| Initial denaturation | 95 | 5 min | 1 |

| Denaturation | 95 | 30 s | 30 - 38 |

| Annealing | 60 | 30 s | |

| Extension | 72 | 30 s | |

| Final extension | 72 | 5 min | 1 |

| RT-PCR | |||

| Initial denaturation | 95 | 15 min | 1 |

| Denaturation | 95 | 15 s | 40 |

| Annealing | 60 | 30 s | |

| Elongation | 72 | 20 s |

Abbreviation: RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction.

3.8. Primer Design and Validation

Primers for the target genes and ACTB (reference gene) were designed using OligoAnalyzer and Primer3 Plus, and validated with BLAST for specificity. Primer efficiencies were calculated using standard curves and fell within the acceptable range of 90 - 110% for both miRNA 146a and ACTB. ACTB primers amplified a 151 bp fragment (forward: 5ˋ-GATCAAGATCATTGCTCCTCCTG-3ˋ, reverse: 5ˋ-CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGAC-3ˋ). GAPDH primers (used for cDNA quality control) amplified a 219 bp fragment (Forward: 5ˋ-TCGGAGTCAACGGATTTG-3ˋ, Reverse: 5ˋ-CCTGGAAGATGGTGATGG-3ˋ).

3.9. Real-time Polymerase Chain Reaction

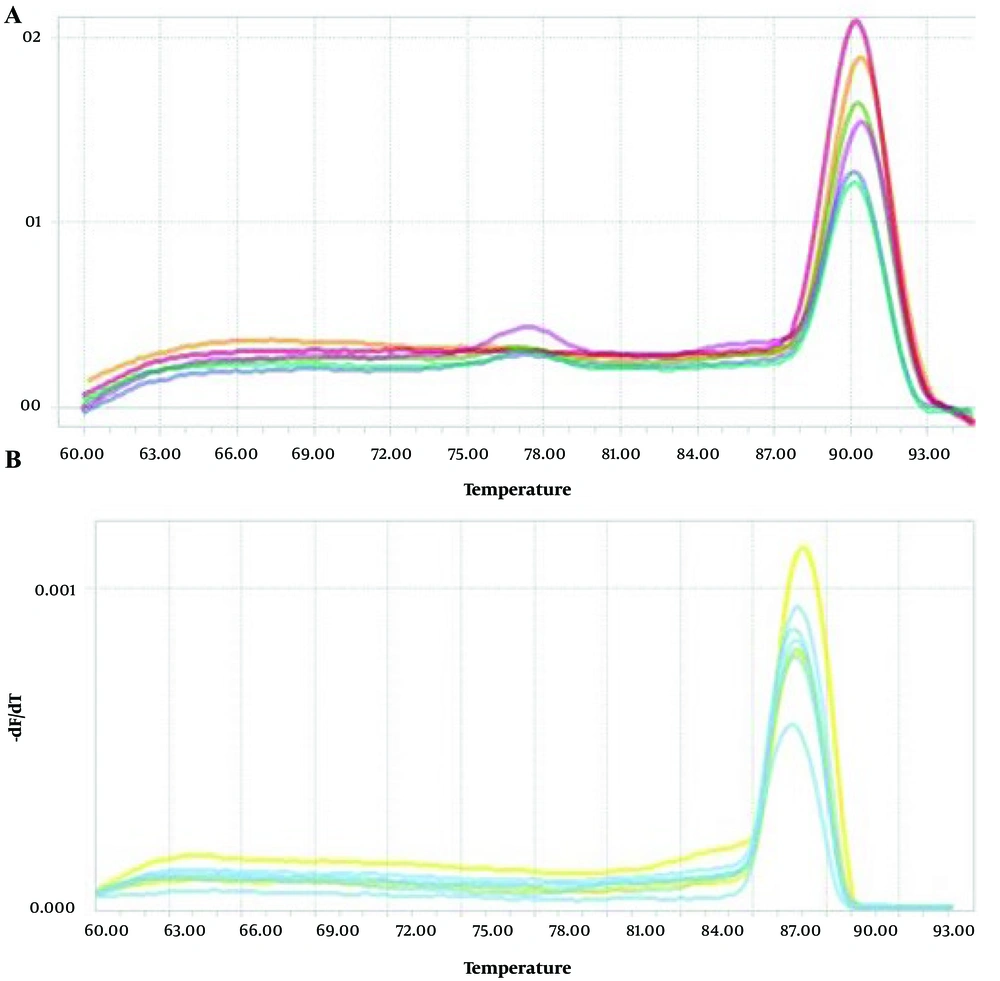

Relative quantification was performed using REST 2009 software, which normalizes target miRNA expression to ACTB as the internal reference gene. ACTB expression was confirmed to be stable across all samples with minimal variation in Ct values. Specific amplification of both miRNA 146a and ACTB was confirmed by melt curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis, ensuring amplification fidelity and product purity.

Expression changes were assessed using RT-PCR with the SYBR-Green kit (Takara Bio; Japan). A master mix including nuclease-free water, primer mix, and SYBR-Green was prepared, and 18 µL was aliquoted per reaction. Following the addition of 2 µL of cDNA, the tubes were run under the following conditions: Initial enzyme activation at 95°C for 15 minutes, denaturation at 95°C for 15 seconds, annealing at 60°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 20 seconds (Table 1). Specific amplification and absence of primer-dimers were confirmed by analyzing melting curves and electrophoresis on 2% agarose gel.

3.10. Data Analysis

Expression data were analyzed using REST 2009 software (Qiagen), which normalizes target gene expression to the reference gene (ACTB) and applies the Pairwise Fixed Reallocation Randomization Test. No ΔCt or ΔΔCt calculations were applied manually. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for group comparisons. A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Due to the high standard deviation (SD) observed in the OSCC group (SD = 4.54), no log transformation or outlier exclusion was applied in this analysis. This decision was based on the limited sample size and the exploratory nature of the study.

4. Results

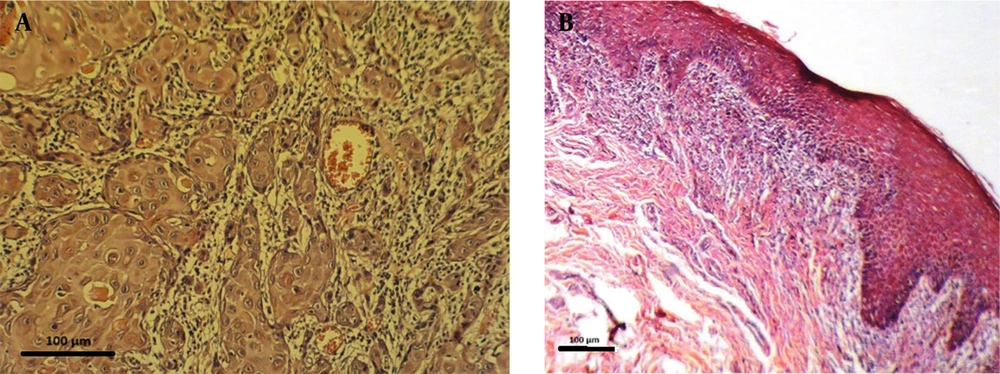

In this study, miRNA 146a expression was measured in 30 OSCC samples and 18 OLP tissue samples. Demographic and clinical variables such as patient age, sex, lesion location, and disease duration were not available due to the retrospective nature of the study and limitations in archived pathology records. The absence of these data introduces potential confounding variables that may influence miRNA expression, such as differences in age-related gene regulation, hormonal influences, anatomical variation, or disease chronicity. Figure 2 shows representative histopathological images of OSCC and OLP tissues, with scale bars and annotations included.

The expression of miRNA 146a was significantly higher in OSCC (4.77 ± 4.54) compared to OLP (1.91 ± 0.97), with a P-value of 0.011. The effect size, calculated using Cohen’s d, was 1.84, indicating a very large magnitude of difference between the two groups (Figure 3A). This corresponds to an approximate 2.5-fold increase.

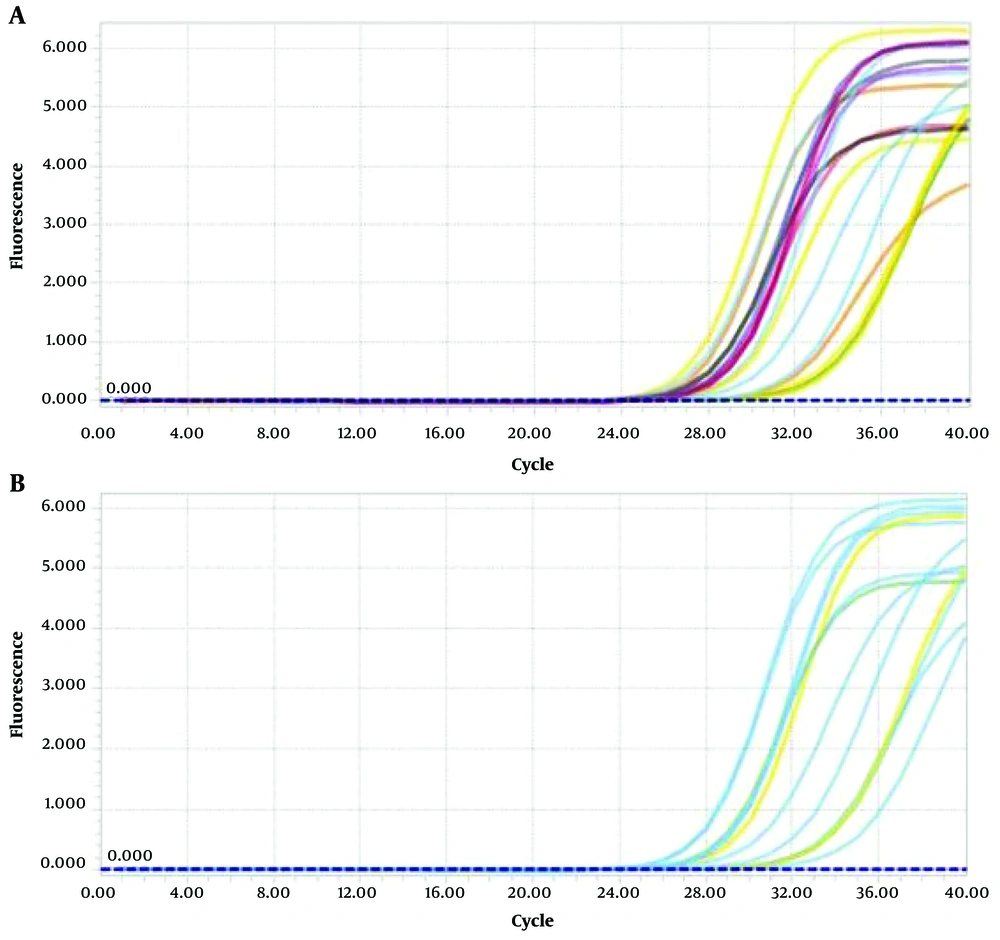

Due to the high SD in the OSCC group, no data transformation or outlier detection was applied; this variability is acknowledged as a study limitation. We have now added a boxplot (Figure 3B) to the Results section to illustrate the distribution and potential outliers in miRNA 146a expression between OSCC and OLP groups. This visual representation complements our statistical analysis and highlights the broader variability in the OSCC group. Figures 4 and 5 illustrate the amplification and melting curves for miRNA 146a and ACTB, confirming the specificity of qPCR amplification.

5. Discussion

This study found significantly higher expression of miRNA 146a in OSCC compared to OLP, indicating its potential role as a biomarker for malignancy risk in OLP lesions. This result is consistent with Hung et al.'s research (28), which showed elevated miRNA 146a levels in OSCC tissues and plasma, and a notable decrease after surgical removal of the tumor. These findings suggest miRNA 146a's potential as a biomarker for OSCC diagnosis and monitoring. Moreover, Hung’s study demonstrated that treatment with a miRNA 146a-blocker significantly weakened xenografted tumor cells, highlighting its potential therapeutic application (28).

Similarly, Dang et al.’s research on miRNA 137 indicated that its activity contributes to the progression of OLP lesions into OSCC via p16 gene methylation (34). Their findings revealed significant increases in p16 methylation in OSCC lesions compared to OLP and healthy tissues. This supports the use of miRNA profiles to assess the risk of malignancy in OLP lesions. Gholizadeh et al. (31) investigated miRNAs regulating the MAPK pathway and found that decreased expression of miRNA-4731 and miRNA-603 was linked to the progression from OLP to OSCC, contrasting with the increase in miRNA 146a observed in this study. These findings suggest that variations in miRNA expression can provide insights into malignant transformation.

Our findings are also consistent with the progression model suggested by Arao et al. (30), who reported significantly higher miRNA 146a expression in OLP lesions compared to healthy oral mucosa. While their study highlighted the inflammatory upregulation of miRNA 146a in OLP, our results extend this pattern by showing even greater expression in OSCC samples. This suggests a possible continuum of miRNA 146a upregulation from inflammatory to malignant states, further supporting its role as a molecular link between chronic inflammation and carcinogenesis.

Additionally, Ikehata et al. (29) explored the role of TLRs in OSCC and found significant overexpression of miRNA 146a. They suggested that miRNA 146a contributes to OSCC progression by suppressing the CARD10 gene, leading to resistance to apoptosis. This reinforces the role of miRNA 146a in OSCC development. The transformation of normal epithelium into a neoplastic state is driven by a series of genetic mutations that disrupt cellular control mechanisms and apoptosis, leading to abnormal cell differentiation (35, 36). These mutations result in increased mitotic activity and enhanced cell survival, creating conditions that favor the accumulation of further genetic alterations and changes in the maturation of epithelial cells. Early stages of carcinogenesis are often marked by alterations in miRNA expression, which can serve as early indicators of malignant transformation (37).

The miRNA 146a regulates multiple oncogenic, immune, and apoptotic pathways by targeting key genes involved in tumor progression, inflammation, and metastasis. In the NF-κB signaling pathway, miRNA 146a downregulates IRAK1 and TRAF6, leading to reduced inflammatory responses and immune evasion, which are critical in chronic inflammation-driven cancers such as OSCC (28, 29). Additionally, miRNA 146a modulates the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway by targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1), influencing cell proliferation, survival, and metabolic adaptation (31). In the TLR pathway, miRNA 146a suppresses TLR2, TLR4, and CARD10, disrupting innate immune signaling and inflammation-associated tumorigenesis. Furthermore, miRNA 146a plays a role in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and metastasis by regulating Notch Regulatory Factor (NUMB) and SMAD family member 4 (SMAD4), which promote cell migration, invasion, and cancer progression (30). In the DNA damage and apoptosis pathways, miRNA 146a influences p16/cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) and breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1), impacting cell cycle arrest and genomic stability, which may contribute to chemoresistance and tumor aggressiveness. Through its broad regulatory network, miRNA 146a plays a central role in OSCC pathogenesis, making it a crucial target for biomarker development and therapeutic interventions.

Our findings demonstrate significantly higher miRNA 146a expression in OSCC lesions compared to OLP, highlighting its potential as a valuable biomarker for assessing malignancy risk and predicting the prognosis of OLP lesions. In addition to the importance of early local treatments, such as tacrolimus, in managing oral mucositis and preventing malignant progression in OLP — thereby enhancing quality of life by reducing lesion severity and associated discomfort — the observed weakening effect of miRNA 146a blockers on cancer cells in preclinical models suggests promising therapeutic applications. Nevertheless, further research with larger cohorts of human samples is essential to validate these findings and comprehensively investigate the therapeutic potential of targeting miRNA 146a.

Also, the observed variability in miRNA 146a expression levels (SD of approximately 50%) is attributed to the inherent biological diversity among samples. Factors such as heterogeneity in lesion stages, genetic differences within the population, and variability in inflammatory responses contribute to this high SD. This variability underscores the complex role of miRNA 146a in the progression of OLP to OSCC, emphasizing the need for further analysis.

While the observed variability in miRNA 146a expression within the OSCC group may reflect true biological heterogeneity or sample-specific effects, the lack of log transformation or formal outlier analysis is a limitation. Incorporating such statistical approaches in future studies could help reduce skewness, normalize distributions, and improve the robustness of differential expression estimates.

While the current study offers valuable insights, it also has some limitations. Firstly, all samples were sourced from the Iranian population, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to more diverse populations. Additionally, the study focused exclusively on well-differentiated OSCC and erosive OLP, as classified by the WHO. While this approach reduces histopathological variability and improves internal consistency, it limits generalizability across the full spectrum of disease severity. Notably, we did not analyze tumor gradation beyond the well-differentiated category; therefore, possible variations in miRNA 146a expression related to tumor differentiation level were not captured. Future studies should include OSCCs of varying grades to assess whether miRNA 146a expression correlates with histological progression or aggressiveness. Furthermore, our study did not analyze sociodemographic and clinical data, such as patient age, gender, and lesion characteristics. This limitation hampers our ability to explore potential correlations between these factors and miRNA expression. Addressing these limitations in future research could help to further validate and expand upon the findings of this study.

In addition to tissue-based analyses, cell line models have been crucial for studying OSCC and related pathologies. Various OSCC cell lines, such as CAL-27, SCC-9, and HSC-3, are commonly used in research to explore tumorigenic processes, miRNA regulation, and drug sensitivity (7). However, to date, there are no well-established cell lines that specifically model the progression from OLP to OSCC. While studies have used OSCC cell lines to investigate potential biomarkers like miRNA 146a, future research efforts should focus on developing or identifying cell line models that can more accurately reflect the early stages of OLP and its transformation to OSCC. Such models would enhance our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying this process and allow for more targeted therapeutic testing.

Despite the valuable insights provided by tissue samples in this study, the lack of dedicated cell line models that accurately mimic the malignant progression of OLP to OSCC highlights an important gap in current research. Future work should prioritize the development of such models to better investigate miRNA-related molecular pathways and explore new therapeutic interventions.

A major limitation of this study is the relatively small and uneven sample size (30 OSCC vs. 18 OLP), which may compromise statistical robustness and limit the generalizability of our findings. This constraint was primarily due to the retrospective design and the limited availability of high-quality, histologically confirmed samples. Additionally, the large SD observed, particularly in the OSCC group, may reflect true biological heterogeneity but also further reduces confidence in effect size estimates. Future prospective, multicenter studies with larger, demographically diverse cohorts are necessary to validate and extend these findings.

Another limitation is the lack of access to comprehensive demographic and clinical information for the samples studied. Because the tissue blocks were retrieved from archival pathology material, variables such as age, sex, lesion location, and lesion duration were not consistently recorded or retrievable. These factors could have influenced miRNA 146a expression and represent potential confounders. For instance, age and sex may impact immune regulation and miRNA profiles, while lesion site and chronicity could affect the local inflammatory environment. We recommend that future prospective studies include these variables to allow stratified analysis and adjust for confounding.

Because this study employed a cross-sectional design, it captures miRNA 146a expression at a single time point without follow-up. Therefore, it does not provide evidence for the predictive or causal role of miRNA 146a in the transformation of OLP to OSCC. The observed expression differences should be interpreted as associative rather than indicative of progression risk. Longitudinal cohort studies are required to establish whether elevated miRNA 146a levels in OLP lesions precede malignant transformation.

Another limitation of our study is the absence of evaluation of inflammation severity in OLP tissues. The miRNA 146a is known to be regulated by inflammatory signaling pathways, and variations in local immune cell infiltration or cytokine activity could influence its expression. Since OLP is a chronic inflammatory disorder with variable activity, failure to quantify or stratify inflammation may have introduced heterogeneity in the expression data. Future studies should incorporate histological or molecular grading of inflammation to clarify the relationship between miRNA expression and inflammatory severity.

Another methodological limitation is that the sample size was not determined through prospective power analysis. This reflects the retrospective nature of the study, which relied on the availability of archived specimens.

Another limitation relates to the high variability in miRNA 146a expression observed within the OSCC group (SD = 4.54). This may reflect true biological heterogeneity; however, no formal outlier detection or data transformation was applied. Future studies should consider using log-transformation or robust statistical models to address variance and identify influential points.

Although miRNA 146a demonstrates significant differential expression between OLP and OSCC, it is unlikely to serve as a standalone diagnostic marker. Instead, its clinical utility may be enhanced when used as part of a multimarker panel alongside other established or emerging miRNAs. So, a further limitation of this study is its exclusive focus on miRNA 146a. While this marker is mechanistically relevant to both inflammatory and neoplastic pathways, evaluating only a single miRNA restricts the breadth of molecular insight. The miRNAs such as miR-21, miR-31, and miR-155 have also been implicated in oral carcinogenesis and may interact synergistically or antagonistically with miRNA 146a. Future studies should employ multi-marker profiling approaches to comprehensively assess miRNA networks and improve diagnostic and prognostic accuracy.

A limitation of this study is the absence of raw qPCR data, such as Ct and ΔCt values, which were not retained due to the use of REST 2009 software for analysis. This tool reports only relative expression and does not store individual amplification values. While commonly used in exploratory settings, this limits reproducibility and transparency. Future studies should include full Ct datasets to enhance validation and data sharing.

Although this study was conducted on a well-defined Iranian cohort, it did not include comparative analysis with other local or regional datasets. This limits the ability to contextualize the observed expression patterns of miRNA 146a within broader epidemiological trends in OSCC or OLP across the Middle East or neighboring regions. While our primary objective was molecular rather than population-based, future research should aim to incorporate regional comparisons to enhance the epidemiological relevance and external validity of biomarker findings.

Although our findings suggest that miRNA 146a expression differs significantly between OLP and OSCC, we did not conduct receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to establish diagnostic thresholds or quantify sensitivity and specificity. This limits our ability to formally evaluate the biomarker’s diagnostic performance. The absence of ROC-based thresholding was due to the small and uneven sample size, which could yield unstable estimates. Future studies with larger and balanced cohorts should include ROC analysis to validate the diagnostic accuracy of miRNA 146a and define clinically meaningful cutoff points.

Another limitation of the current study is the absence of correlation between miRNA 146a expression and histopathological severity or specific microscopic features of OLP and OSCC lesions. Factors such as epithelial thickness, ulceration, lymphocytic infiltration, dysplasia in OLP, or invasion depth and perineural spread in OSCC were not systematically recorded or analyzed. This limits the clinical applicability of our findings in stratifying lesion severity or prognostic potential. Future research should include standardized histopathologic scoring and correlate these variables with miRNA expression to better define clinical relevance.

Another limitation is the absence of ROC curve analysis to evaluate the diagnostic performance of miRNA 146a. Without ROC-based metrics such as sensitivity, specificity, and area under the curve (AUC), we cannot determine an optimal diagnostic threshold or validate the clinical utility of this marker. This was primarily due to the limited and unbalanced sample size, which would likely yield unstable estimates. Future studies with larger, prospectively recruited cohorts should include ROC analysis to formally assess biomarker performance.

5.1. Conclusions

This study identified significantly higher expression of miRNA 146a in OSCC compared to OLP, suggesting its potential role as a diagnostic biomarker to distinguish malignant from premalignant oral lesions. However, due to limitations in sample size, variability, and lack of longitudinal data, these findings should be interpreted as associative rather than predictive. Future multicenter, prospective studies incorporating multi-marker panels and robust statistical methods are needed to confirm the clinical utility of miRNA 146a in oral lesion management.