1. Background

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a prevalent and disabling musculoskeletal condition, particularly affecting older adults. The condition is characterized by symptoms such as knee joint pain, stiffness, and functional limitations, all of which severely diminish quality of life and can lead to disability. This condition imposes a significant burden on healthcare systems globally, highlighting the need for effective symptom management and treatment strategies (1). The probability of developing osteoarthritis (OA) rises progressively with advancing age. The prevalence of KOA is highest among individuals aged 70 to 74, reaching up to 40% (2).

The OA is a multifaceted condition influenced by interactions among joint structures, including cartilage, subchondral bone, synovial tissue, ligaments, surrounding fat pads, menisci, and adjacent muscles. Typical radiographic signs of OA involve joint space narrowing, which results from the deterioration of articular cartilage and meniscal tissue. Additionally, bone-related changes such as subchondral sclerosis and the formation of osteophytes (bone spurs) are commonly observed (3).

The cause of cartilage degeneration is not well understood. It is thought that mechanical and enzymatic factors cause dysfunction of cartilage cells and damage to the matrix (4).

However, several internal (endogenous) factors contribute to the risk of developing KOA. These include advanced age, biological sex, genetic predisposition, ethnic background — with a higher prevalence noted among individuals of European descent — and hormonal changes following menopause (4). External risk factors for KOA include macrotrauma, repetitive microtrauma, overweight, joint resection, lifestyle factors (such as alcohol consumption and smoking), post-trauma, malformation, varus/valgus deformities, post-surgical changes, rickets, hemochromatosis, chondrocalcinosis, achondrosis, acromegaly, and hyperparathyroidism.

Individuals diagnosed with OA commonly experience joint pain and limited mobility, particularly in the form of stiffness. Pain is initially associated with physical activity but becomes less predictable over time. Therefore, OA is sometimes considered an inevitable and progressive condition (5).

The typical radiographic features of KOA, as seen on plain radiographs, are categorized using the Kellgren-Lawrence grading system, which ranges from 0 to 4 (6).

Clinical recommendations emphasize that individuals with OA should initially be managed through a core package of non-pharmacological interventions (7). These include patient education, weight reduction for those with excess body mass, and various forms of physical activity — ranging from resistance training and aerobic exercise to mind-body approaches such as yoga or Tai Chi (8).

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are typically regarded as the first-line pharmacological option for managing symptoms associated with OA. For participants who either cannot tolerate NSAIDs or show an insufficient response, intra-articular corticosteroid injections may be considered. These injections generally offer short-term pain relief, typically lasting for several weeks (9). Intra-articular injections of hyaluronic acid derivatives represent an additional therapeutic option for individuals who continue to experience pain despite NSAID therapy.

Emerging regenerative therapies, including growth factor-based injections such as platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and stem cell preparations, are attracting growing interest in the management of OA. Beyond surgical and invasive procedures, a variety of non-invasive conservative treatments are available. These include physiotherapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), acupuncture, thermal therapies such as localized heat or cold application, and laser-based modalities (10).

Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy is an evolving and widely applicable treatment method for musculoskeletal disorders (11).

Exercise therapy is widely recognized as a core component of non-pharmacological management for KOA. Clinical guidelines from the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommend aerobic training, strengthening exercises, and flexibility routines to alleviate pain, enhance joint function, and improve overall mobility. Structured exercise programs have been shown to reduce inflammation, delay disease progression, and substantially enhance quality of life in participants with moderate to severe KOA (12).

The PEMF therapy utilizes time-varying magnetic fields generated by strong electrical currents flowing through a coil. Clinicians can precisely control and adjust the frequency, intensity, and waveform of these magnetic pulses (13).

The PEMF therapy is well-tolerated, non-invasive, and easy to administer. This method effectively reduces pain, improves function in arthritis, accelerates wound healing, reduces inflammation, and facilitates tissue repair in the foot. Studies also show that it may promote the growth of cartilage cells (14).

A study by Ryang We et al., involving 482 participants with OA, found PEMF therapy to be substantially more effective than placebo at both 4 and 8 weeks. An analysis of fourteen trials (482 in the treatment group and 448 in the placebo group) initially demonstrated no significant pain relief across all time points. However, high-quality trials revealed PEMF to be significantly more effective than placebo at both 4 and 8 weeks. Functional improvement was notable 8 weeks post-treatment, with a standardized mean difference of 0.30 (15).

A study by Bagnato et al. demonstrated that 60 participants with KOA experienced significant improvement in pain [Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)] and function [Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)] scores following one month of PEMF therapy applied for at least 12 hours per day (16).

Iannitti et al. investigated 28 elderly participants with bilateral KOA. The right leg received PEMF therapy (30 minutes, 3 times per week for 6 weeks) in addition to intravenous medications (ketoprofen, sodium clodronate, glucosamine sulfate, calcitonin, and ascorbic acid), while the left leg served as the control. The PEMF therapy significantly improved pain relief (VAS score), reduced stiffness, and enhanced physical function (WOMAC score) three months after treatment (17).

Despite numerous randomized controlled trials, a consensus or clear guideline for clinicians to tailor PEMF therapy regimens — specifically regarding the duration, frequency, and intensity of sessions — remains elusive.

2. Objectives

This study aims to investigate the efficacy of PEMF therapy in participants with OA, summarize the current body of evidence, and propose strategies to enhance the quality of future research.

3. Methods

This randomized, single-blind clinical trial was conducted at the Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinic of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS). The study protocol was registered with the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCTID: IRCT20231007059642N1) and approved by the Ethics Committee (IR.MUI.MED.REC.1402.242).

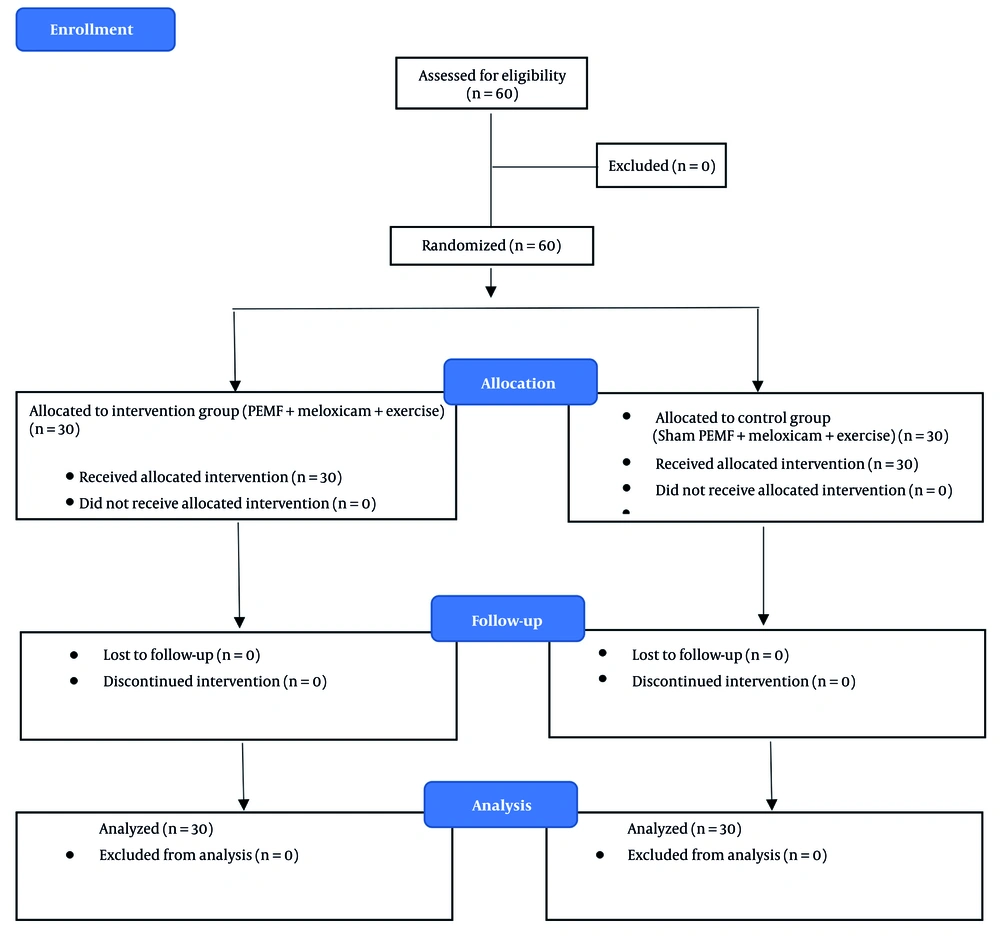

The sample size was determined a prior using the formula for comparing two independent means. Assuming a minimal clinically important difference (MCID) of 1.5 points on the VAS, a standard deviation (SD) of 2.0, α = 0.05, and 80% power, the required sample size was 27 per group. Considering a 10% dropout rate, 30 participants were recruited per group, yielding a total of 60 participants. Convenience sampling was used to recruit eligible participants, who were then randomly allocated into two groups — PEMF and sham — according to a computer-generated random allocation sequence (Figure 1).

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

To be included, participants were required to be at least 40 years old with a diagnosis of grade II or III KOA according to the ACR criteria. They needed to have experienced symptoms for at least six months, including stiffness and daily pain with an intensity of ≥ 3 on the VAS, and a WOMAC score greater than 48.

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Participants were excluded if they had received intra-articular medication within the past six months; recent systemic corticosteroid use or physiotherapy within the last six weeks; knee pain resulting from non-OA causes (e.g., malignancy, autoimmune, inflammatory, or structural defects); a history of prior knee surgery; poor compliance; pregnancy; or the presence of metal implants such as pacemakers.

3.3. Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomly allocated (1:1) to the PEMF group or the sham-PEMF group using a computer-generated random sequence with permuted blocks of four. Allocation concealment was maintained using sequentially numbered, sealed opaque envelopes prepared by an independent researcher who was not involved in participant recruitment.

Due to the nature of the intervention, complete participant blinding was challenging. However, all participants — regardless of group allocation — were explicitly informed at the beginning of the study that the PEMF device would not produce any heat, vibration, or tactile sensation during therapy. They were told that such characteristics were typical and that it was normal not to feel anything during treatment, even when the device was active. As a result, no participant was able to determine whether the device was active or inactive, which helped maintain effective blinding and minimize expectation bias.

Both participants and outcome assessors were blinded to group allocation. The sham device was identical in appearance to the active one; however, it did not generate an active magnetic field. The treating physician was not blinded due to the nature of the intervention.

3.4. Interventions

The intervention group received eight sessions of PEMF therapy (30 minutes per session over three weeks), in addition to meloxicam (15 mg daily for 18 days) and a standardized home-based exercise program. The exercise program consisted of isometric strengthening and static stretching exercises targeting the quadriceps and hamstring muscles, performed three times per day. Each session included three sets of 20-second contractions or stretches per muscle group (Table 1) (18).

| Components; Exercise Type/Description | Frequency and Duration | Intensity and Progression | Supervision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strengthening | |||

| Isometric quadriceps contractions (knee extension, no movement) | Sets × 20-second, 3 contractions, 3 times/d | Submaximal effort; maintain contraction without pain | Trained individually; technique checked at each PEMF/sham visit |

| Stretching | Trained individually; technique checked at each PEMF/sham visit | ||

| Static quadriceps stretching | Sets × 20-second, 3 contractions, 3 times/d | Hold to mild discomfort; no bouncing | |

| Static hamstring stretching | Sets × 20-second, 3 contractions, 3 times/d | Hold to mild discomfort; no bouncing |

Abbreviation: PEMF, pulsed electromagnetic field.

At the beginning of the study, participants were individually trained to ensure correct performance of the exercises. During each PEMF (or sham) therapy visit, exercise techniques were assessed and corrected as needed. Following the intervention period, during the follow-up phase, participants were routinely questioned to monitor continued adherence to the exercise program.

The control group received the same meloxicam dosage and exercise program as the intervention group; however, instead of active PEMF therapy, they received treatment using a sham device with no electromagnetic output.

3.5. Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Protocol

Patients in the intervention group were positioned supine on a treatment table. A PEMF device (Magno 915G) pulsed by a 70 cm solenoid was applied to the exposed knee area. The PEMF parameters used in this study (75 Hz frequency, 50 Gauss intensity, protracted waveform, 44% duty cycle, for 30 minutes per session, three times per week for eight sessions) were selected based on a combination of previously published research demonstrating efficacy in OA and the clinical protocol recommended by the device manufacturer (15).

3.6. Control Group Protocol

Patients in the control group received the same pharmacological and exercise interventions as the intervention group. Specifically, they were prescribed 15 mg of meloxicam daily for 18 days and followed the same home-based exercise program consisting of isometric strengthening and stretching of the quadriceps and hamstrings. The exercises were performed three times daily, with three sets of 20-second holds per session.

To maintain blinding and minimize placebo-related bias, a sham PEMF device — identical in appearance to the active device — was applied during treatment sessions. Patients were informed that the device does not produce any heat, vibration, or other sensations during use. This explanation was provided to all participants to ensure that they could not distinguish between active and sham PEMF treatment.

3.7. Outcome Measures

3.7.1. Visual Analog Scale

Pain intensity was measured using a VAS, with scores ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain imaginable).

3.7.2. Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

This self-administered Questionnaire assessed the severity of KOA. It measures three key domains:

- Pain: Assessed using 5 items.

- Stiffness: Assessed using 2 items.

- Physical function: Assessed using 17 items.

Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = none/no difficulty; 4 = extremely severe/unable to perform). The Persian version of WOMAC was used in the current study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.811, an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.80, and an acceptable correlation with the medical outcomes study 20-item short form (MOS-SF-20) (19). Outcomes were evaluated at baseline (before treatment), immediately after treatment, and at 6 and 12 weeks after the last treatment session.

3.8. Procedures

Baseline assessments were performed at enrollment (week 0). Post-intervention assessments were conducted immediately after completion of treatment. Follow-up assessments were performed at weeks 6 and 12 to evaluate the persistence of treatment effects. All measurements were performed by a trained, blinded clinician.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 22. Descriptive statistics were presented as mean ± SD or frequencies (%). Baseline characteristics were compared between groups using independent t-tests or chi-square tests, as appropriate.

For primary and secondary outcomes, a repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine within-group and between-group changes over time. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was additionally performed, adjusting for baseline values (including age, if significant differences existed between groups). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Bonferroni correction.

Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

The mean age of all participants was 57.87 ± 7.80 years (range, 40 - 70), with most being female (70.0%). The intervention group had a mean age of 61.27 ± 5.57 years, and the control group had a mean age of 54.47 ± 8.29 years. A significant difference in mean age was observed between the groups (P < 0.001); however, there was no significant difference in gender distribution (P = 0.091). The ANCOVA was used to control for the effect of age (Table 2).

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

a Independent samples t-test.

b Chi-square (χ2).

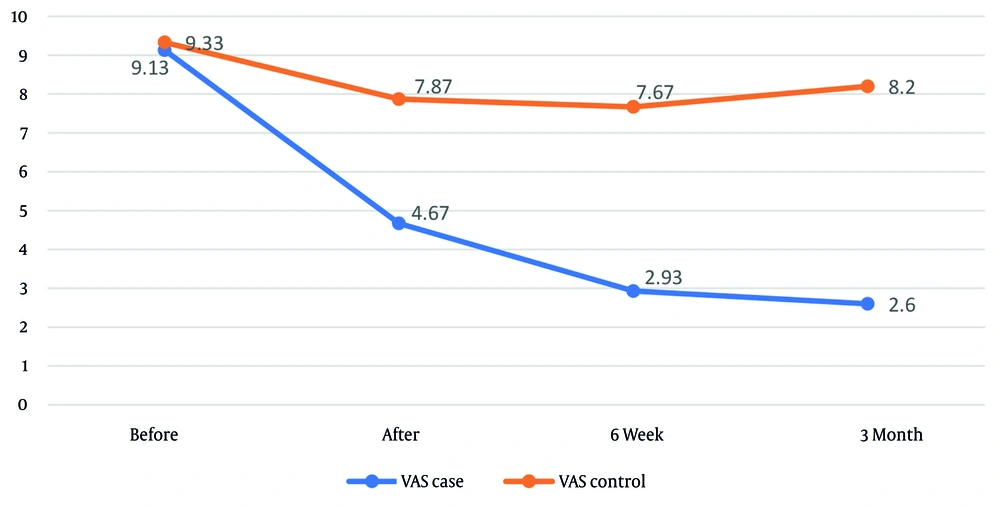

Pain, as measured by the VAS (Table 3), was assessed over time in both the intervention and control groups. The ANCOVA revealed no significant difference in baseline pain scores between groups prior to intervention (P = 0.391). However, at all post-intervention time points — immediately, 6 weeks, and 3 months after treatment — the intervention group reported substantially lower pain compared to the control group (P < 0.001 for all).

| Pain; Groups | Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the End of Treatment | Immediately After Completion of Treatment | 6 wk After Completion of Treatment | 3 mo After Completion of Treatment | P (One-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA) | |

| Pain based on the VAS Scale | |||||

| Intervention | 9.13 ± 1.38 | 4.67 ± 1.72 | 2.93 ± 1.59 | 2.60 ± 1.73 | < 0.001 |

| Control | 9.33 ± 0.88 | 7.87 ± 1.65 | 7.67 ± 1.56 | 8.20 ± 1.90 | < 0.001 |

| P (covariance analysis) | - | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | - |

| ⴄ2 | 0.391 | 0.454 | 0.691 | 0.686 | - |

| Total pain score based on the WOMAC Scale | |||||

| Intervention | 79.93 ± 13.23 | 30.33 ± 12.40 | 23.20 ± 10.59 | 20.80 ± 9.76 | < 0.001 |

| Control | 85.87 ± 6.71 | 71.20 ± 16.96 | 77.40 ± 19.10 | 85.33 ± 7.77 | < 0.001 |

| P (covariance analysis) | - | < 0 .001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | - |

| ⴄ2 | 0.150 | 0.589 | 0.706 | 0.924 | - |

| Pain subscale | |||||

| Intervention | 17.13 ± 3.17 | 6.87 ± 2.43 | 5.00 ± 2.57 | 4.27 ± 2.36 | < 0.001 |

| Control | 18.53 ± 1.85 | 13.73 ± 3.75 | 15.93 ± 4.14 | 17.80 ± 1.49 | < 0.001 |

| P (covariance analysis) | - | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | - |

| ⴄ2 | 0.082 | 0.443 | 0.645 | 0.931 | - |

| Joint stiffness subscale | |||||

| Intervention | 6.73 ± 2.42 | 3.20 ± 1.82 | 1.87 ± 1.10 | 1.73 ± 1.01 | < 0.001 |

| Control | 6.67 ± .88 | 5.67 ± 1.51 | 6.07 ± 1.55 | 6.67 ± 1.02 | < 0.001 |

| P (covariance analysis) | - | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | - |

| ⴄ2 | 0.785 | 0.354 | 0.686 | 0.871 | - |

| Physical performance subscale | |||||

| Intervention | 55.73 ± 10.63 | 22.67 ± 6.68 | 16.33 ± 7.40 | 14.20 ± 7.56 | < 0.001 |

| Control | 59.33 ± 6.88 | 52.80 ± 12.04 | 55.87 ± 12.64 | 60.87 ± 6.10 | < 0.001 |

| P (covariance analysis) | - | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | - |

| ⴄ2 | 0.471 | 0.651 | 0.755 | 0.921 | - |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

The magnitude of the intervention effect was greatest at 3 months post-treatment (0.686) and smallest immediately after treatment (0.454). Following treatment completion, mean pain scores were 3.40 ± 1.54 in the intervention group and 7.91 ± 1.66 in the control group (P < 0.001). The overall effect size of the intervention was 0.656. Repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that pain significantly changed over time within both the intervention and control groups (Figure 2).

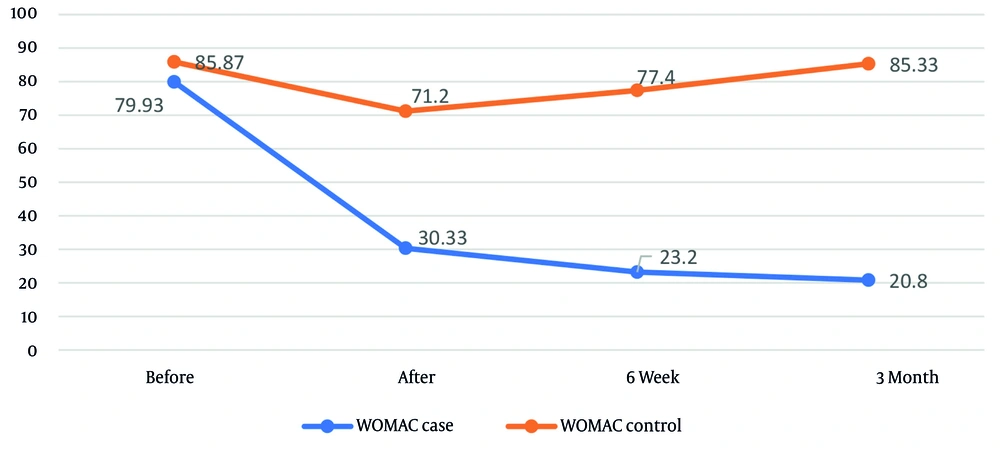

The ANCOVA revealed no significant difference in WOMAC pain scores and subscales between the groups before the intervention (P > 0.05). However, at all post-intervention time points, the intervention group exhibited substantially lower WOMAC scores than the control group (P < 0.001). The intervention’s effect size on WOMAC scores was greatest at 3 months post-treatment and smallest immediately after treatment (Figure 3). Repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that WOMAC scores and subscales changed significantly over time within both the intervention and control groups (P < 0.001 for both, Table 3).

The two-way Bonferroni test revealed significant pain reductions within both groups (Table 4). In the intervention group, pain was substantially lower at all post-intervention time points compared to baseline (P < 0.001), and pain continued to decrease over time. In the control group, pain was substantially lower at all post-intervention time points compared to baseline (P < 0.05), with pain at 6 weeks significantly lower than at 3 months (P = 0.002). Baseline VAS pain scores were 79.93 ± 13.23 and 85.87 ± 6.00, while post-treatment scores were 24.77 ± 9.34 (intervention) and 77.97 ± 13.05 (control).

| Pain; Groups | Before˜ Immediately Afterwards | Before˜ 6 wk Later | Before˜ 3 mo Later | Immediately Afterwards˜ 6 wk Later | Immediately Afterwards˜ 3 mo Later | 6 wk Later˜ 3 mo Later |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain based on the VAS | ||||||

| Intervention | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.004 |

| Control | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.025 | 0.338 | 0.094 | 0.002 |

| Total pain score based on the WOMAC Scale | ||||||

| Intervention | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.797 |

| Control | < 0.001 | 0.105 | 0.999 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.100 |

| Pain subscale | ||||||

| Intervention | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.009 |

| Control | < 0.001 | 0.029 | 0.028 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | 0.101 |

| Joint stiffness subscale | ||||||

| Intervention | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.999 |

| Control | 0.003 | 0.173 | 0.999 | 0.031 | 0.004 | 0.144 |

| Physical performance subscale | ||||||

| Intervention | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.024 |

| Control | 0.031 | 0.941 | 0.999 | 0.020 | < 0.001 | 0.032 |

Abbreviations: VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; WOMAC, Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index.

The ANCOVA confirmed that post-treatment VAS pain was significantly lower in the intervention group (P < 0.001; effect size = 0.821). Similarly, the intervention group demonstrated substantially lower scores on the WOMAC subscales for pain (5.37 ± 2.17 vs. 15.82 ± 2.54, P < 0.001; effect size = 0.799), joint stiffness (2.26 ± 1.15 vs. 6.13 ± 1.19, P < 0.001; effect size = 0.725), and physical function (17.73 ± 6.56 vs. 56.51 ± 9.59, P < 0.001; effect size = 0.829).

In the intervention group, the two-way Bonferroni test (Table 4) revealed significant differences in total WOMAC scores and stiffness subscale scores at all time points, except for the comparison between 3 months and 6 weeks post-treatment (P < 0.001). Pain and physical function subscale scores were significantly lower at all three post-intervention time points compared to baseline and continued to decrease over time (P < 0.001).

In the control group, WOMAC pain scores and all subscales decreased significantly immediately after treatment compared to baseline but increased significantly at 6 weeks and 3 months after treatment compared to immediately post-treatment (P < 0.05). The findings further demonstrated that pain subscale scores decreased significantly at 6 weeks and 3 months after treatment compared to baseline, whereas physical function subscale scores increased significantly at 3 months compared to 6 weeks after the intervention (P = 0.032; Table 3).

The observed reductions in both VAS and WOMAC scores exceeded their respective MCID thresholds (VAS ≥ 1.5 cm; WOMAC ≥ 12 points), indicating that the improvements were not only statistically significant but also clinically meaningful.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the effect of magnet therapy on participants with grade II and III OA. The results demonstrated a significant reduction in pain, as measured by both the VAS and WOMAC Scales. The greatest reduction in pain was observed three months after the intervention, while the smallest reduction occurred immediately following the intervention. Additionally, significant improvements in physical function and joint stiffness were noted at follow-up compared with the control group. However, the magnitude of pain reduction was greater than the improvements observed in physical functioning and joint stiffness.

The findings indicate that PEMF therapy, when combined with meloxicam and structured exercise, produces superior improvements in pain and function compared with the control group. Nonetheless, because exercise therapy is an evidence-based intervention for OA, its contribution to the observed outcomes should be acknowledged. The synergistic effects of PEMF and exercise may explain the magnitude of improvement reported in this study.

One limitation of this study is the absence of a PEMF-only treatment group, which restricts the ability to isolate the independent effect of PEMF therapy. Including a third group receiving PEMF alone could have provided more insight into its specific contribution. Regarding blinding, although a single-blind design was used, all participants were explicitly informed that the PEMF device would not produce any heat, vibration, or other sensations — regardless of whether it was active or inactive. This approach minimized the risk of unblinding and reduced potential placebo- or expectation-related bias. Nonetheless, the exercise protocol, although standardized, may not be generalizable to other clinical settings.

These findings align with previous research suggesting that PEMF can reduce inflammation and stimulate tissue repair. For example, Iannitti et al. reported that PEMF therapy in participants with bilateral KOA significantly decreased pain but did not alter stiffness or physical functioning. Notably, the Iannitti et al. study employed PEMF for 30 minutes, three times per week for six weeks, in combination with intravenous medication. Consistent with Iannitti et al., the present study also demonstrated a more pronounced reduction in pain compared with improvements in stiffness and physical function (17).

In the study by Elboim-Gabyzon and Nahhas, the effect of magnet therapy was compared with low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in patients with KOA. The results demonstrated that PEMF therapy significantly reduced pain on the WOMAC Scale and improved timed up and go (TUG) test results compared with LLLT, indicating superior efficacy. The PEMF sessions were conducted over six sessions in three weeks, with each session lasting 15 minutes. Therefore, the present study is fully consistent with their findings (20).

In the study by Xu et al., the combined effect of PEMF and PRP therapy was investigated in patients with primary KOA. Participants were divided into three groups: The PEMF alone, PRP alone, and a combination of both. The PEMF sessions were administered once daily, five times per week, for 12 weeks, while PRP was injected once per month for three months. The results showed that pain reduction based on the VAS Scale was greater in the combined treatment group than in the other two groups, and knee mobility improved significantly. Therefore, the current study aligns with their findings, although the number of PEMF sessions in our protocol was fewer, and the effect of PEMF therapy was evaluated independently (21).

In the study by Bagnato et al., PEMF therapy was administered for 12 hours daily for one month. The results demonstrated that the treatment significantly reduced pain. Thus, our study is consistent with their findings, although the number and duration of sessions in our protocol were considerably shorter (16).

Importantly, the mean changes in pain and function scores exceeded the established MCID thresholds for KOA, confirming that the improvements observed were not only statistically significant but also clinically relevant and likely to be perceived as beneficial by participants.

No complications were reported during the study period. However, this study had several limitations. A primary limitation was the relatively small sample size and the short follow-up duration. In addition, the study was not fully blinded. One of the strengths of this investigation was the inclusion of a sham therapy in the control group, which strengthened the methodological rigor. Future studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are needed to confirm these findings and to evaluate the long-term effects of PEMF therapy.

5.1. Conclusions

The PEMF therapy appears to be a promising adjunct treatment for improving pain and physical function in participants with KOA.

5.2. Limitations

The study did not include a PEMF-only treatment group, which limits the ability to isolate the independent effects of PEMF therapy. Although a single-blind design was employed, maintaining participant blinding is inherently challenging in device-based interventions. To mitigate this, all participants — regardless of group assignment — were informed at the outset that the PEMF device would not generate any perceptible sensations such as heat, vibration, or light. This information was provided uniformly to prevent assumptions about treatment allocation. We believe this approach minimized expectation bias and helped maintain blinding integrity. However, a degree of perceptual bias cannot be completely excluded.

A significant age imbalance was also present between groups at baseline, although statistical adjustment was applied using ANCOVA to account for this difference. Furthermore, the standardized exercise protocol used in this study lacked external validation and may not be generalizable across diverse clinical or cultural settings.