1. Background

Disability, as defined by the International Classification of Functioning (ICF), Disability and Health, refers to a deficiency or limitation that affects an individual's social participation (1). This condition may involve deficiencies in body functions or structures, limitations in performing activities, and restrictions in participation. Accordingly, the ICF classifies the severity of disability into various degrees: "No disability", "mild", "moderate", and "severe" (1, 2), which allows for interventions to be tailored to the specific needs of different populations.

Among the types of functional disability, those related to manual dexterity and mobility are distinguished (2). The latter refers to difficulties in movement and walking, often necessitating the use of assistive devices such as canes or wheelchairs. Meanwhile, dexterity-related disability, also known as fine motor impairment, involves limitations in performing fine manual tasks such as writing, handling objects, or dressing oneself (2, 3). In this context, the ICF, developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) (4), provides a comprehensive framework for describing health, encompassing body functions, activities, participation, and contextual factors. However, due to its complexity, the ICF's application in population-based surveys is limited, prompting the development of adapted tools such as the Washington Group on Disability Statistics' classification (5), which recommends the use of self-reported questions to assess domains including vision, hearing, mobility, cognition, and self-care.

In the Peruvian context, the approach to disability has been gradually integrated into public health policies and official records. The Ministry of Health of Peru, through its "Technical Health Standard" (2), employs the term "mobility and dexterity disability" to refer to functional limitations affecting the movement and use of upper and lower limbs. In this context, the First National Penitentiary Census was conducted in 2016 by the Instituto National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, in collaboration with the Instituto Nacional Penitenciario of Peru, representing a significant milestone by collecting data on health and disability among the incarcerated population (2, 3). The implementation of such tools within the penitentiary system is particularly relevant, as it is a vulnerable population whose living conditions, characterized by overcrowding, poor nutrition, limited medical services, and chronic stress, contribute to deteriorating health. However, the data collected have not yet been analyzed from a perspective that links disability with other health conditions, such as chronic diseases. Although there is extensive literature addressing the associations between various factors related to these conditions and disability in the general population, studies examining these relationships specifically among incarcerated individuals are considerably more limited. This highlights an important research gap and underscores the need for more in-depth analysis within the prison context.

Among the most common chronic diseases in this population are respiratory, cardiovascular, and metabolic conditions — including diabetes mellitus (6) — which are prevalent in prison populations and associated with risk factors such as age, lifestyle, and incarceration conditions (7, 8). Despite their high prevalence, these diseases have been scarcely studied in prison contexts. For instance, in Spain (9), 50% of individuals deprived of liberty suffer from chronic conditions such as dyslipidemia, hypertension, diabetes, and respiratory diseases. Furthermore, incarcerated individuals with disabilities and chronic illnesses often face discrimination and inadequate medical care (10).

2. Objectives

Therefore, it is essential to identify the presence of chronic diseases in prison populations and examine their association with functional disabilities, such as mobility and dexterity impairments. Although it is well known that chronic diseases and disabilities are common in prison settings, this association has not been quantitatively explored in the Peruvian context using robust and nationally representative data. Such analysis would contribute to strengthening epidemiological surveillance systems and improving the quality of healthcare services within the prison system.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The design of this study is analytical and cross-sectional in nature, based on the analysis of a secondary database corresponding to the 2016 National Prison Population Census (11).

3.2. Study Population and Sample

The study population consisted of 76,180 individuals deprived of liberty incarcerated in 66 correctional facilities nationwide, administered by the National Penitentiary Institute of Peru in 2016. The inclusion criteria were individuals aged 18 years or older, of both sexes, who participated in the census and self-reported the presence or absence of chronic diseases. Individuals who did not respond to questions regarding mobility and dexterity disability were excluded. Additionally, for the analysis of exposure factors, those who did not provide information on pulmonary disease, hypertension, and/or diabetes were excluded. These conditions were identified in the census form using a coding system, in which P107_1 corresponded to pulmonary disease, P107_2 to hypertension, P107_3 to diabetes, and P113_1 to mobility and dexterity disability.

3.3. Variables and Measurement Instrument

This study utilized data from the First National Penitentiary Census of Peru, specifically from the health section of the Census Questionnaire. This self-administered instrument consisted of 405 questions, developed based on the Washington Group on Disability Statistics, which allows for large-scale data collection. The health section collected self-reported information on chronic disease diagnoses made by healthcare professionals. The responses were compiled into a secondary database used for the present analysis. Additionally, a group of enumerators was trained to administer the questions to inmates in order to obtain accurate information.

3.3.1. Mobility and Dexterity Disability

This variable was assessed through question P113_1: "Do you have permanent problems moving or walking, or using your arms and legs?" Respondents were instructed to consider “permanent” any functional limitation that was irreversible and that affected their activities of daily living. Those who responded affirmatively were asked to self-assess the severity of their disability (mild, moderate, or severe) based on the level of limitation experienced in such activities.

3.3.2. Chronic Diseases

Three chronic diseases were considered: Diabetes, hypertension, and chronic respiratory diseases (asthma, bronchitis, or emphysema), as these were the only conditions specifically recorded in the instrument. Other conditions, such as obesity, were not included due to the lack of data on weight and height. Similarly, disorders such as depression or anxiety were excluded, as they were grouped under the category “other diseases” along with conditions like cancer, allergies, and anemia, among others, which hindered their proper classification.

For chronic diseases, a composite variable was constructed using two questionnaire items: One on self-report of the condition (P107), in which respondents answered “yes/no” regarding the presence of the disease, and a subsequent question on medical confirmation (P107_1), which asked whether a healthcare professional had diagnosed the condition. Individuals who reported having the disease and had a professional diagnosis were classified as “Yes”, while all others were classified as “No”.

3.3.3. Multimorbidity

A variable for multimorbidity was created to identify individuals presenting none, one, two, or all three of the aforementioned chronic diseases at the time of the census.

3.4. Procedures

3.4.1. Data Collection

A secondary database obtained from the official website of the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics of Peru was used for this study.

3.4.2. Data Analysis

The collected database was downloaded and organized into five coded folders for use with SPSS software. Subsequently, the files were integrated, relevant variables were selected, and the data were transferred to Stata 14 software for analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA 14 (Stata Corp-Texas). A descriptive analysis of categorical variables was conducted using absolute frequencies, relative frequencies, and percentages. For the bivariate analysis, the association between the dependent variable (mobility disability, including locomotion and dexterity) and the independent variables (chronic diseases) was assessed. The chi-square test (chi2) was applied, considering associations with a P-value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

In the multivariate analysis, crude and adjusted prevalence ratios (PRs) were calculated with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI), and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A Poisson regression model with robust variance was used.

A Poisson regression model with robust variance was used to estimate PR and their 95% CIs. This approach was chosen over the log-binomial model because of its numerical stability and convergence reliability, particularly when outcome prevalence is high or covariates are correlated, as recommended in previous methodological studies.

The adjusted models included potential confounding variables between the exposure and the outcome (mobility disability). Additionally, the absence of multicollinearity among included variables was verified.

- Model 1: Sociodemographic variables: Sex, age, and educational level.

- Model 2: Lifestyle-related variables: Drug use, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and participation in sports activities.

- Model 3: Chronic diseases (pulmonary, hypertension, and diabetes), in addition to sex, age, educational level, drug use, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and participation in sports activities.

- Model 4: Sex, age, educational level, drug use, alcohol consumption, tobacco use, and participation in sports activities.

3.4.3. Ethical Consideration

The study was approved by the Ethics Subcommittee of the Faculty of Health Sciences at Peruvian University of Applied Sciences (CEI/071-06-19// PI051-19). Data collection was conducted ethically and authorized by Ministerial Resolution, with the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics and the General Directorate of Criminal and Penitentiary Policy designated as responsible for the census. Both institutions assigned trained personnel to carry out the fieldwork.

4. Results

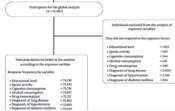

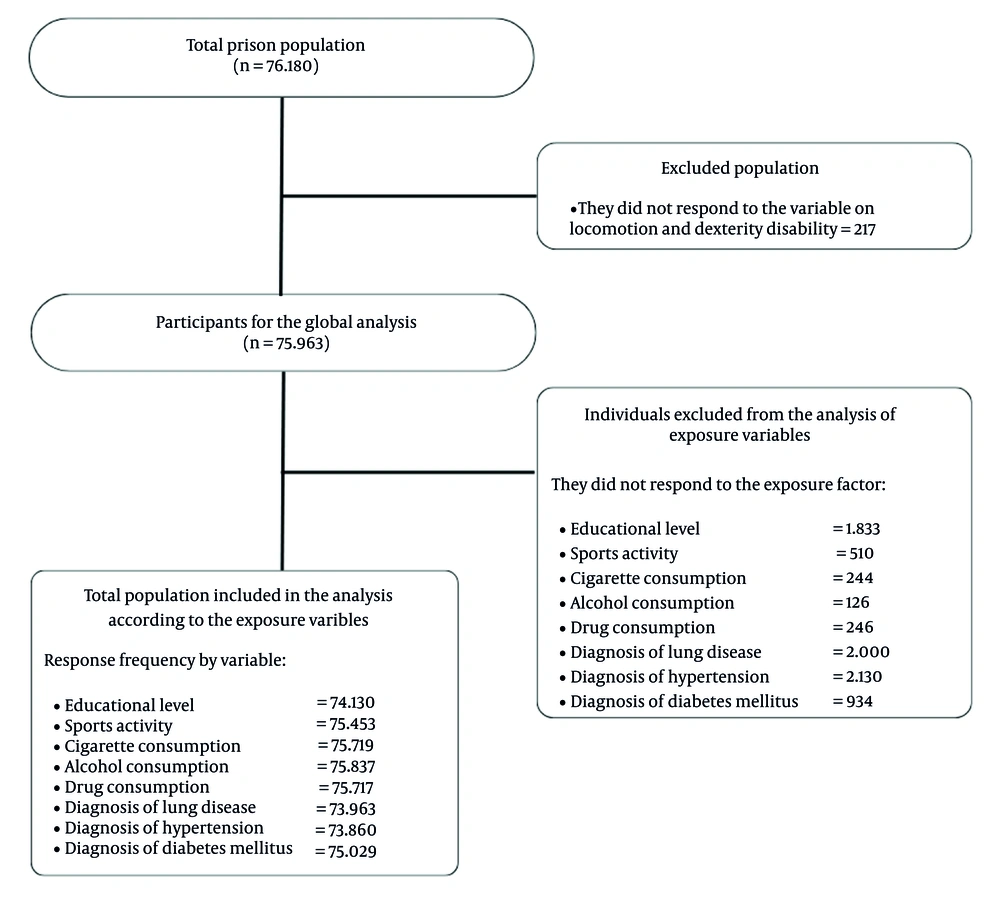

The first national penitentiary population census of 2016 recorded a total of 76,180 participants. For this study, individuals who did not respond to the outcome variable representing locomotion and dexterity disability were excluded (n = 217). As a result, 75,963 inmates were included in the final population analyzed in the study (Figure 1).

4.1. Population Characteristics

A total of 75,963 inmates who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the study. The majority of the prison population was male (94%), which may result in different outcomes when compared to the female population. Furthermore, the largest age group was early adulthood (30 - 34 years), representing 43.26% of the total. Additionally, 32.65% reported not having completed secondary education. A higher percentage of the population reported consuming alcoholic beverages (67.59%), while 65.1% stated they currently engage in sports activities (Table 1).

| Characteristics | No. (%), N = 75,963 |

|---|---|

| Sex (n = 75,963) | |

| Male | 71,416 (94.01) |

| Female | 4,547 (5.99) |

| Age group (n = 75,963) | |

| Young | 12,254 (16.13) |

| Young adult | 13,827 (18.2) |

| Early adult | 32,865 (43.26) |

| Middle adult | 14,031 (18.47) |

| Late adult | 2,986 (3.93) |

| Marital status (n = 75,963) | |

| Common-law marriage | 28,965 (38.13) |

| Married | 8,947 (11.78) |

| Widowed | 992 (1.31) |

| Divorced | 775 (1.02) |

| Separated | 2,905 (3.82) |

| Sigle | 33,379 (43.94) |

| Education level (n = 74,130) | |

| No education level | 1,675 (2.26) |

| Early childhood education | 106 (0.14) |

| Incomplete primary education | 11,762 (15.87) |

| Complete primary education | 6,897 (9.3) |

| Incomplete secondary education | 24,200 (32.65) |

| Completed secondary education | 20,293 (27.37) |

| Incomplete non-university higher education | 2,572 (3.47) |

| Completed non-university higher education | 2,795 (3.77) |

| Incomplete university higher education | 2,075 (2.8) |

| Completed university higher education | 1,673 (2.26) |

| Postgraduate | 82 (0.11) |

| Sport activities (n = 75,453) | |

| Yes | 49,117 (65.1) |

| No | 26,336 (34.9) |

| Cigarette consumption (n = 75,719) | |

| Yes | 25,187 (33.26) |

| No | 50,532 (66.74) |

| Alcohol consumption (n = 75,837) | |

| Yes | 51,259 (67.59) |

| No | 24,578 (32.41) |

| Drug consumption (n = 75,717) | |

| Yes | 18,641 (24.62) |

| No | 57,076 (75.38) |

a The data obtained from the missing population corresponds to the participants who did not answer the question or for whom information was not available.

Regarding health and disability, 7,402 inmates (9.74% of the total population) reported having locomotion and dexterity problems. When breaking down the severity of the disability, 39.44% were classified as mild, 37.08% as moderate, and 23.48% as severe. Furthermore, the proportion of the population with chronic diseases diagnosed by a physician was as follows: Pulmonary disease 6.3% (4,660 individuals), hypertension 4.8% (3,574 individuals), and diabetes 2.5% (1,897 individuals). Among those with these conditions, only 56.7% reported receiving treatment (Table 2).

| Characteristics (Health and Disability) | No. (%), N = 75,963 |

|---|---|

| Presence of locomotion and dexterity disability | |

| No | 68,561 (90.26) |

| Yes | 7,402 (9.74) |

| Level of disability to move | |

| Mild | 2,919 (39.44) |

| Moderate | 2,745 (37.08) |

| Severe | 1,738 (23.48) |

| Suffering from pulmonary disease (n = 73,963) | |

| No | 69,303 (93.7) |

| Yes | 4,660 (6.3) |

| Treatment for pulmonary disease (n = 4,660) | |

| No | 2,420 (51.93) |

| Yes | 2,240 (48.07) |

| Suffering from hypertension (n = 73,860) | |

| No | 70,286 (95.16) |

| Yes | 3,574 (4.84) |

| Treatment for hypertension (n = 3,574) | |

| No | 1,371 (38.36) |

| Yes | 2,203 (61.64) |

| Suffering from diabetes (n = 75,029) | |

| No | 73,132 (97.47) |

| Yes | 1,897 (2.53) |

| Treatment for diabetes (n = 1,897) | |

| No | 593 (31.26) |

| Yes | 1,304 (68.74) |

| Chronic multimorbidity (n = 71,602) | |

| None of the three | 63,200 (88.27) |

| One disease | 7,338 (10.25) |

| Two diseases | 966 (1.35) |

| Three diseases | 98 (0.14) |

a The data obtained from the missing population corresponds to the participants who did not answer the question or for whom information was not available.

4.2. Factors Associated with Locomotion and Dexterity Disability

A significant association was observed between various sociodemographic variables and locomotion and dexterity disability (P < 0.001). However, no association was found with sports activity (P = 0.26) or cigarette consumption (P = 0.76, Table 3). Regarding health-related variables, a significant association was established between most of them and locomotion and dexterity disability (P < 0.001), except for the variable "treatment for hypertension" (P = 0.14). The analysis of the association between multimorbidity (pulmonary disease, hypertension, and diabetes) and locomotion and dexterity disability was also significant (P < 0.001, Table 4).

| Characteristics (Sociodemographic) | Locomotion and Dexterity Disability (N = 75,963) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P a | |

| Sex (n = 75,963) | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 6,820 (9.55) | 64,596 (90.45) | |

| Female | 582 (12.8) | 3,965 (87.2) | |

| Age group (n = 75,963) | < 0.001 | ||

| Young | 590 (4.81) | 11,664 (95.19) | |

| Young adult | 853 (6.17) | 12,974 (93.83) | |

| Early adult | 2,908 (8.85) | 29,957 (91.15) | |

| Middle adult | 2,156 (15.37) | 11,875 (84.63) | |

| Late adult | 895 (29.97) | 2,091 (70.03) | |

| Marital status (n = 75,963) | < 0.001 | ||

| Common-law marriage | 2,667 (9.21) | 26,298 (90.79) | |

| Married | 1,295 (14.47) | 7,652 (85.53) | |

| Widowed | 219 (22.08) | 773 (77.92) | |

| Divorced | 120 (15.48) | 655 (84.52) | |

| Separated | 352 (12.12) | 2,553 (87.88) | |

| Sigle | 2,749 (8.24) | 30,630 (91.76) | |

| Education level (n = 74,130) | < 0.001 | ||

| No education level | 290 (17.31) | 1,385 (82.69) | |

| Early childhood education | 17 (16.04) | 89 (83.96) | |

| Incomplete primary education | 1,631 (13.87) | 10,131 (86.13) | |

| Complete primary education | 719 (10.42) | 6178 (89.58) | |

| Incomplete secondary education | 2,148 (8.88) | 22,052 (91.12) | |

| Completed secondary education | 1,596 (7.86) | 18,697 (92.14) | |

| Incomplete non-university higher education | 211 (8.2) | 2,361 (91.8) | |

| Completed non-university higher education | 240 (8.59) | 2,555 (91.41) | |

| Incomplete university higher education | 177 (8.53) | 1,898 (91.47) | |

| Completed university higher education | 161 (9.62) | 1,512 (90.38) | |

| Postgraduate | 10 (12.2) | 72 (87.8) | |

| Sport activities (n = 75,453) | 0.264 | ||

| Yes | 4,824 (9.82) | 44,293 (90.18)0 | |

| No | 2,520 (9.57) | 23,816 (90.43) | |

| Cigarette consumption (n = 75,719) | 0.757 | ||

| Yes | 2,440 (9.69) | 22,747 (90.31) | |

| No | 4,931 (9.76) | 45,601 (90.24) | |

| Alcohol consumption (n = 75,837) | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 4,814 (9.39) | 46,445 (90.61) | |

| No | 2,577 (10.48) | 22,001 (89.52) | |

| Drug consumption (n = 75,717) | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 1,985 (10.65) | 16,656 (89.35) | |

| No | 5,392 (9.45) | 51,684 (90.55) | |

a P-values obtained through the chi-square test (chi2).

| Characteristics (Health) | Locomotion and Dexterity Disability (N = 75,963) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P a | |

| Suffering from pulmonary disease (n = 73,963) | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 6,148 (8.87) | 63,155 (91.13) | |

| Yes | 885 (18.99) | 3,775 (81.01) | |

| Treatment for pulmonary disease (n = 4,660) | 0.002 | ||

| No | 419 (17.31) | 2,001 (82.69) | |

| Yes | 466 (20.8) | 1,774 (79.2) | |

| Suffering from hypertension (n = 73,860) | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 5,939 (8.45) | 64,347 (91.55) | |

| Yes | 1,007 (28.18) | 2,567 (71.82) | |

| Treatment for hypertension (n = 3,574) | 0.14 | ||

| No | 367 (26.77) | 1,004 (73.23) | |

| Yes | 640 (29.05) | 1,563 (70.95) | |

| Suffering from diabetes (n = 75,029) | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 6,661 (9.11) | 66,471 (90.89) | |

| Yes | 543 (28.62) | 1,354 (71.38) | |

| Treatment for diabetes (n = 1,897) | 0.001 | ||

| No | 140 (23.61) | 453 (76.39) | |

| Yes | 403 (30.9) | 901 (69.1) | |

| Chronic multimorbidity (n = 71,602) | < 0.001 | ||

| None of the three | 4,729 (7.48) | 58,471 (92.52) | |

| One disease | 1,434 (19.54) | 5,904 (80.46) | |

| Two diseases | 329 (34.06) | 637 (65.94) | |

| Three diseases | 55 (56.12) | 43 (43.88) | |

a P-values obtained through the chi-square test (chi2).

4.3. Association Between Locomotion and Dexterity Disability and Exposure to Chronic Diseases

A significant association (P < 0.001) was established between the variables analyzed in each model and locomotion and dexterity disability among individuals exposed to chronic diseases (Table 5). As a result, the prevalence of locomotion and dexterity disability was 3.33 times higher among individuals with hypertension compared to those without. Moreover, the likelihood of experiencing this type of disability increases 7.5 times when all three chronic conditions (respiratory disease, hypertension, and diabetes) are present simultaneously (PR = 7.63, 95% CI: 6.40 - 9.09).

| Chronic Diseases | Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model 1 | Unadjusted Model 2 | Adjusted Model 3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR | IC 95% | P | PR | IC 95% | P | PR | IC 95% | P | PR | IC 95% | P | |

| Pulmonary disease | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | ||||||||

| Yes | 2.14 | 2.00 - 2.28 | 1.83 | 1.72 - 1.96 | 2.12 | 1.98 - 2.26 | 1.63 | 1.52 - 1.75 | ||||

| Hypertension | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.33 | 3.14 - 3.53 | 2.25 | 2.11 - 2.40 | 3.38 | 3.19 - 3.58 | 1.94 | 1.81 - 2.09 | ||||

| Diabetes | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | ||||||||

| Yes | 3.14 | 2.91 - 3.38 | 2.09 | 1.93 - 2.26 | 3.15 | 2.92 - 3.40 | 1.71 | 1.56 - 1.87 | ||||

| Multimorbidity (HTA, EPC y diabetes) | Unadjusted Model | Adjusted Model 1 | Unadjusted Model 2 | Adjusted Model 4 | ||||||||

| PR | IC 95% | P | PR | IC 95% | P | PR | IC 95% | P | PR | IC 95% | P | |

| None of the three | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | 1 - Reference | ||||||||

| One disease | 2.61 | 2.47 - 2.75 | < 0.001 | 2.07 | 1.95 - 2.19 | < 0.001 | 2.6 | 2.46 - 2.74 | < 0.001 | 2 | 1.89 - 2.12 | < 0.001 |

| Two diseases | 4.55 | 4.15 - 4.98 | < 0.001 | 2.99 | 2.71 - 3.30 | < 0.001 | 4.61 | 4.20 - 5.06 | < 0.001 | 2.89 | 2.62 - 3.20 | < 0.001 |

| Three diseases | 7.5 | 6.28 - 8.95 | < 0.001 | 4.23 | 3.53 - 5.07 | < 0.001 | 7.63 | 6.40 - 9.09 | < 0.001 | 3.91 | 3.25 - 4.70 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a Model 1: Adjusted for sex, age, and educational level; model 2: Adjusted for drug use, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and sports activities; model 3: Adjusted for chronic diseases (pulmonary, hypertension, and diabetes), sex, age, educational level, drug use, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and sports activities; model 4: Adjusted for sex, age, educational level, drug use, alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and sports activities.

b P obtained using a generalized linear Poisson model with robust variances.

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates that incarcerated individuals with respiratory disease are 2.12 times more likely to develop locomotion and dexterity disability. Likewise, individuals with diabetes have 3.15 times higher, and those with hypertension are 3.138 times more likely to develop it. Furthermore, having all three chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes, and chronic respiratory diseases) results in a 7.63 times greater likelihood of experiencing locomotion and dexterity disability compared to those without these conditions, even after adjusting for factors such as drug, alcohol, tobacco use, and sports activities.

5.1. Pulmonary Disease and Locomotion and Dexterity Disability

Our findings show an association between respiratory disease and a higher prevalence of locomotion and dexterity disability, with an adjusted PR of 2.12 (95% CI: 1.98 - 2.26). This aligns with studies linking COPD to an increase in years lived with disability (YLD), which rose globally from 2.3% in 1990 to 2.9% in 2019, positioning COPD as the sixth leading cause of YLD (12). In COPD, ventilatory function progressively deteriorates due to loss of pulmonary elasticity and increased airway resistance, leading to symptoms such as dyspnea and cough. Physical activity in individuals with COPD can exacerbate these symptoms by inducing pulmonary hyperinflation and functional limitation, ultimately contributing to disability (13). Consequently, these patients tend to experience muscle atrophy in the limbs, further contributing to the burden of disability associated with COPD (14).

In prison settings, the prevalence of respiratory diseases is high, mainly associated with both active and passive smoking (15, 16). This has prompted policy reviews to improve surveillance and interventions, which should be maintained post-release due to the high risk of relapse and re-exposure (17, 18).

5.2. Hypertension and Disability in Mobility and Dexterity

A significant association was found between arterial hypertension and a higher prevalence of locomotion and dexterity disability, with an adjusted PR of 3.38 (95% CI: 3.19 - 3.58). While it remains under debate whether HTN leads to disability or vice versa, studies have shown that reduced mobility and slower gait speed are associated with a higher risk of HTN (17-19).

This relationship may be due to neurological damage, such as brain microlesions caused by HTN (20), which affect motor control and mobility. Therefore, HTN is not only a cardiovascular risk factor but is also associated with physical disability, falls, and mobility limitations (21). In turn, physical disability may increase the risk of HTN due to limitations in self-care. However, increasing physical activity and making lifestyle modifications may help reduce this risk in individuals with disabilities (22, 23).

5.3. Diabetes and Disability in Locomotion and Dexterity

Regarding diabetes, our study found that it increases the prevalence of locomotion and dexterity disability, with an adjusted PR of 3.15 (95% CI: 2.92 - 3.40), consistent with the literature on its growing disability burden (24, 25). Diabetes-related complications include stroke, heart disease, neuropathy, cancer, and functional disability. Between 47% and 84% of individuals with diabetes experience functional limitations in the lower limbs (26), contributing to increased disability (27) and a higher risk of dementia (28). Diabetes often coexists with cognitive decline, stroke, and depression (29, 30). Diabetic neuropathy is associated with greater mobility-related disability (31). In prison settings, comorbidity with depression is common among older inmates, and dietary habits significantly influence diabetes management (32, 33). Additionally, cardiovascular risk factors are prevalent in this population (34).

5.4. Multimorbidity and Disability in Locomotion and Dexterity

Our results show that the probability of locomotion and dexterity disability increases significantly in the presence of all three chronic diseases (multimorbidity), with an adjusted PR of 7.63 (95% CI: 6.40 - 9.09). Evidence suggests that chronic diseases increase the risk of disability and that adequate management may delay its onset (35). However, due to the cross-sectional design of this study, it is not possible to establish a definitive causal relationship between chronic conditions and locomotion and dexterity disability. This type of analysis does not allow for determining the temporal order of events; therefore, it is possible that pre-existing disability contributed to the development of chronic diseases or that unmeasured factors influenced both conditions. Nevertheless, studies have shown that these factors exhibit a bidirectional relationship, in which diseases can lead to disability, and disability can, in turn, increase disease risk. Previous studies have also highlighted the influence of muscle strength and body weight on the development of both chronic diseases and disability (36, 37). Therefore, it is recommended to analyze multimorbidity rather than individual diseases, as the combination of conditions amplifies the risk, as reflected in our data, where multimorbidity exceeds the sum of individual PRs (15).

In this context, incarcerated populations face a high risk of chronic conditions, exacerbated by adverse prison conditions such as overcrowding, older age, sentence duration, and insufficient medical care (38). In addition, unhealthy lifestyles in prison, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, and sleep disorders contribute to the development of chronic diseases and functional decline (39). This has been observed in inmates over 50 years of age, who present a high prevalence of chronic diseases attributable to physical inactivity and poor diets rich in fats and sodium (38). A significant association has also been demonstrated between a history of incarceration and the development of morbidity and mortality linked to cardiovascular disease. Overcrowded and confined conditions result in low physical activity levels and poor nutritional status, affecting inmates' quality of life (38). Although the social model of disability predominates, the constraints of confinement exacerbate these issues. Nonetheless, chronic diseases and disabilities are not inherent to incarceration; thus, targeted preventive strategies and interventions, such as disability acceptance, and pain and fatigue management, are essential to improve inmates' quality of life (40). Likewise, the periodic assessment of disability in incarcerated individuals could allow for its early identification and reduce potential complications.

Additionally, the lack of information regarding the duration of incarceration, as well as access to and quality of health and rehabilitation services within prisons, limits the ability to fully contextualize the observed associations and to control for unmeasured confounding factors. Additionally, the use of self-reported data without verification through medical records represents another significant limitation of this study, as such instruments may underestimate or overestimate the measurement of disability or chronic disease. These findings highlight the importance of implementing routine screening for functional disability in prison settings. Such screening would not only enable the early identification of individuals with mobility and dexterity limitations but could also guide the more efficient allocation of limited rehabilitation resources, prioritizing those with multimorbidity and greater vulnerability within the prison system.

Moreover, the use of self-reported data without verification through medical records represents another significant limitation of this study, as such instruments may underestimate or overestimate the measurement of disability or chronic disease. These findings underscore the importance of implementing routine screening for functional disability in prison settings. Such screening would not only allow for the early identification of individuals with mobility and dexterity limitations but could also guide a more efficient allocation of available rehabilitation resources, prioritizing those with multimorbidity and greater vulnerability within the prison system.

5.5. Conclusions

The presence of diabetes, respiratory diseases, arterial hypertension, and their comorbidities increases the prevalence of locomotion and dexterity disability among incarcerated individuals in Peruvian prisons.