1. Background

Community-based interventions are recognized as promising strategies for health promotion and disease prevention, although their full potential has not yet been realized (1). These interventions often employ multiple strategies, such as social participation, education, and environmental changes, which can lead to improved behaviors and health outcomes (2). Community participation is crucial for the success of health promotion programs, as it enhances the community’s support and capacity to engage in preventive activities (2, 3). Studies have shown that community participation can lead to positive health outcomes, including increased knowledge and awareness, improved self-efficacy, and better development of health services (3). Some community-based programs have demonstrated significant successes, such as the Healthy Heart Isfahan program, which effectively improved dietary behaviors in a developing country (1, 4). Furthermore, community-based participatory research has been effective in addressing health disparities and improving knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to specific health issues, such as intimate partner violence (5). Despite these successes, community-based health promotion programs often face challenges, including methodological limitations, contextual effects, and difficulties in achieving widespread population changes (1, 2). Addressing these challenges is necessary to fully realize the potential of community-based interventions.

Recent studies suggest that the promotion of kindness in communities can help address these challenges by fostering social cohesion and mutual support, which are critical for effective health promotion. Kindness, by strengthening mutual support and social connections, plays a key role in developing stronger and more supportive communities. Such social cohesion is essential for the success of community health programs, as it encourages collaboration and participation in health promotion activities (6, 7). Acts of kindness have been linked to improved mental health, reduced stress, and better physical health outcomes, such as lower blood pressure and reduced inflammation (8-10). These benefits can enhance the overall effectiveness of community health programs (11, 12).

Kindness promotes positive social interactions that are crucial for reducing feelings of isolation and improving well-being. Stronger social networks support community health initiatives by encouraging members to engage in health-promoting behaviors (7, 13, 14). Acts of kindness can also encourage others to adopt similar behaviors, creating a positive cycle that can amplify the impact of community health efforts (15-17). Promoting kindness can help reduce aggression and violence, leading to safer and more cohesive communities. This environment is essential for the success of community-based health initiatives (18-21).

Evidence supports the importance of community-based health promotion in improving health outcomes and addressing health inequalities (22), highlighting the need for continued investment in community capacity building and participatory approaches. The development of kindness can help overcome the challenges of community health promotion by strengthening community cohesion, improving health outcomes, enhancing social connections, fostering positive social change, and reducing conflict (7).

Existing evidence indicates that innovative, culturally sensitive, and participatory approaches are necessary to reduce inequalities and improve health outcomes at the community level. Within this framework, promoting kindness has emerged as an effective strategy for enhancing social and psychological health. This study aims to elucidate the role of kindness in improving community-based health and to highlight its contribution to strengthening social cohesion and addressing health challenges.

The rationale for this study is fourfold: First, kindness has a positive impact on mental and social health. It can improve social relationships, reduce stress and anxiety, and strengthen social support networks. This is particularly important because many health and social problems stem from a lack of social support and chronic stress. Therefore, promoting kindness can mitigate these issues and directly enhance mental and social well-being.

Second, kindness fosters social cohesion by building empathy and encouraging participation in social activities. In communities with strong cohesion and cooperation, individuals are more likely to engage in health-promoting behaviors, leading to improved quality of life. This social cohesion is essential not only for individual well-being but also for managing collective health challenges.

Third, kindness contributes to conflict reduction and increased cooperation. Social discord can significantly hinder health promotion efforts in many communities. Kindness acts as a catalyst for dialogue and conflict resolution, improving relationships and fostering cooperation, which ultimately benefits public health.

Lastly, this research seeks to deepen understanding of the cultural and social prerequisites for promoting community-based health. The qualitative approach allows for nuanced exploration of kindness within specific cultural contexts, facilitating the development of more effective and culturally appropriate health programs.

2. Objectives

Overall, this study is essential to identify and clarify the role of kindness in promoting community health, providing new insights and practical strategies to strengthen social cohesion and improve health outcomes at the community level. The findings will contribute to the growing body of knowledge on community-based health promotion and inform the design of interventions that harness the power of kindness to enhance social and psychological well-being.

3. Methods

This conventional qualitative study was conducted from 23 November 2023 (23/08/1402) to 20 July 2024 (30/04/1403), involving 58 participants, including clients, healthcare managers, and academic as well as executive experts affiliated with the Ministry of Health and the Iran University of Medical Sciences.

Participants were selected through purposive sampling to ensure a diverse representation of expertise, professional roles, and experiences relevant to community-based health promotion. This strategy enabled the capture of a wide range of perspectives, particularly regarding the socio-cultural aspects of kindness in Tehran. Interviews were held in various settings, including Tehran municipality offices, Iran University of Medical Sciences campuses, and the Heart Center Hospital. Eligible individuals were identified through professional networks, official email invitations, formal letters, and direct referrals from key informants within the organizations, ensuring a systematic and transparent recruitment process.

The study was initiated after obtaining ethical approval from the Research and Technology Department of Iran University of Medical Sciences (IR.IUMS.REC.1402.709). The research strictly adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained before participation, and verbal consent was reconfirmed at the start of each interview. Confidentiality and anonymity were rigorously maintained, and participants were informed of their right to withdraw at any time without consequences.

3.1. Data Saturation and Sample Size Justification

Data saturation was reached after 58 interviews, with no new themes emerging in the final sessions. Although qualitative studies often involve smaller samples, the relatively larger number of participants was intentionally chosen to ensure comprehensive coverage of diverse professional backgrounds, community roles, and levels of engagement with health promotion programs. This approach strengthened the credibility and transferability of the findings.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

1. Inclusion criteria:

- Executive, managerial, or service delivery experience in health or related fields.

- Awareness and involvement in social and community health initiatives.

- Willingness and ability to participate actively in in-depth interviews.

2. Exclusion criteria:

- Inability or unwillingness to provide informed consent.

- Limited familiarity with community health initiatives.

- Language barriers or communication difficulties preventing effective participation.

This sampling ensured representation from key stakeholder groups, including service users, administrators, and academic or executive experts, providing a holistic understanding of kindness in community health contexts.

3.3. Data Collection

Data were collected using semi-structured, in-depth interviews, guided by a protocol developed specifically for this study. The main guiding questions were:

- How can kindness contribute to the development of community-based interventions?

- What role can the promotion of kindness in society play in improving community health?

Follow-up and probing questions were employed flexibly to clarify ambiguous responses and deepen understanding. Interviews lasted 45 - 75 minutes, were audio-recorded with participants’ consent, and were accompanied by detailed field notes capturing contextual and non-verbal cues.

Prior to each interview, participants were fully briefed on the study objectives, with assurances of confidentiality and anonymity. Participants’ perspectives were carefully documented, ensuring that ethical and methodological rigor was maintained throughout.

3.4. Ethical Considerations and Validation

All interviews were transcribed verbatim immediately after completion. To enhance credibility, member checking was conducted: Transcripts were returned to participants for review and feedback, ensuring accurate representation of their views.

Expert input was incorporated where participants introduced novel ideas, and these concepts were explored further in follow-up sessions, maintaining a comprehensive and rigorous approach to data collection.

3.5. Coding and Data Analysis

Systematic coding and thematic analysis followed Guba and Lincoln’s criteria for trustworthiness: Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (23-25).

1. Credibility: Ensured through member checking, prolonged engagement with participants, and iterative verification of codes.

2. Dependability: Achieved by involving an external auditor experienced in qualitative research to review coding, category formation, and thematic interpretation.

3. Confirmability: Maintained by independent qualitative experts reviewing coding and theme extraction.

4. Transferability: Assessed by comparing findings with similar studies in the literature (26, 27).

Triangulation was applied at multiple levels:

1. Data triangulation: Including healthcare workers, community leaders, and residents.

2. Methodological triangulation: Integrating interview data with field notes and peer debriefing sessions.

3. Expert review: Three qualitative research experts validated the coding framework and thematic structure.

3.6. Data Analysis Framework

Data were analyzed manually using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic content analysis framework (28, 29): (1) Familiarization with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, (6) producing the final report. All interviews were transcribed verbatim immediately after data collection. The process of moving from raw data to 54 initial codes, 8 subthemes, and 4 main themes was performed systematically, documented through an audit trail, and reviewed by both the research team and independent qualitative experts.

Step-by-step coding procedure:

1. Open coding: (A) each transcript was read multiple times to identify meaningful units of text. (B) initial codes (n = 54) were generated line-by-line, capturing explicit statements and implicit meanings related to kindness and community health.

2. Axial coding/grouping: Codes with similar concepts or patterns were grouped together to form categories, based on relationships and underlying dimensions. Example: Codes related to “emotional support”, “listening to others”, and “empathy in interactions” were grouped under the subtheme “Emotional-Social Well-being”.

3. Theme formation: Categories were further analyzed to identify overarching subthemes (n = 8) and main themes (n = 4), reflecting the broader dimensions of kindness in community health. The main themes included: (A) mental and emotional well-being; (B) social cohesion and community support; (C) health promotion and public engagement; (D) social equity and inclusion.

4. Validation and rigor: (A) member checking was conducted by returning transcripts and preliminary codes to participants for feedback. (B) independent qualitative experts reviewed the coding framework and thematic structure to ensure credibility, confirmability, and dependability. (C) triangulation was applied by integrating interview data with field notes, observational records, and peer debriefing.

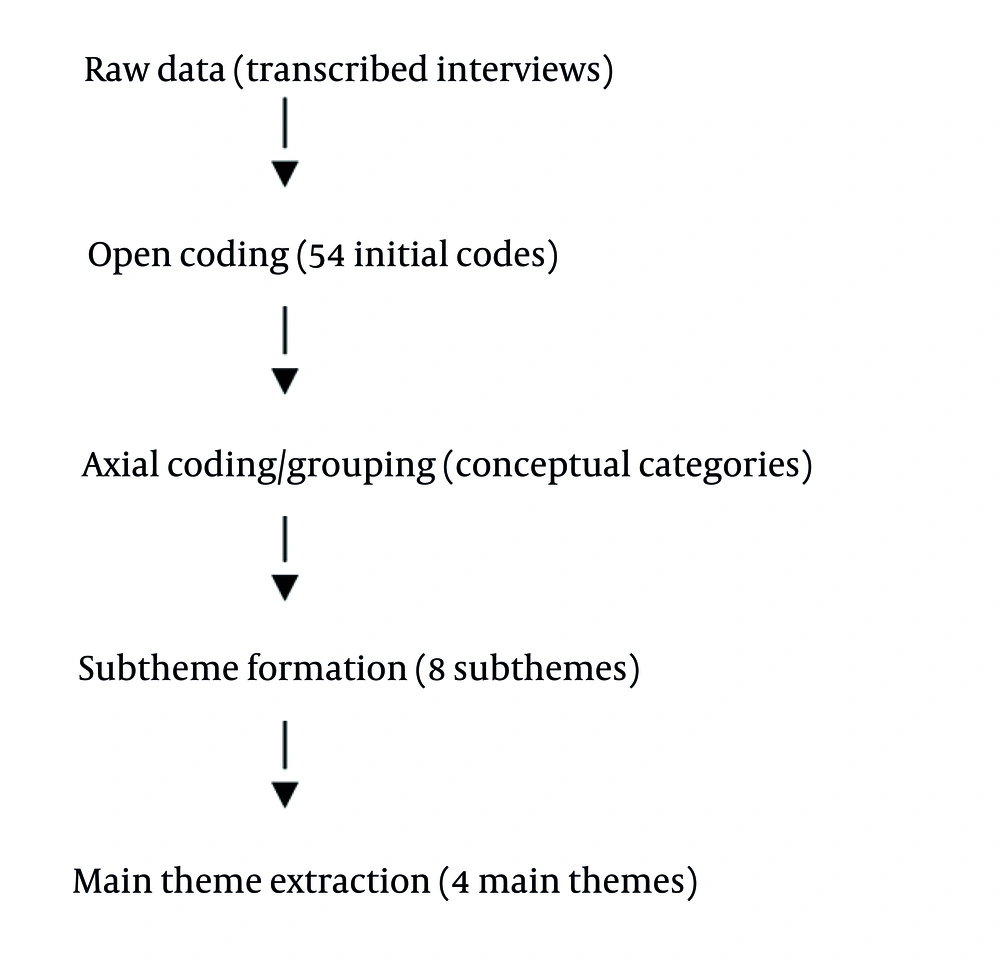

3.7. Flow Diagram

The following flow diagram (Figure 1) depicts the systematic process from raw data to the identification of main themes.

Manual analysis was chosen due to the Persian language of the interviews, allowing nuanced interpretation and context-sensitive theme development that automated software might limit. The transition from 54 codes to 8 subthemes and 4 main themes was performed systematically, documented through an audit trail, and cross-validated by the research team and independent experts to ensure transparency, rigor, and reproducibility.

4. Results

A total of 58 participants were involved in the study, representing a diverse range of professional roles, educational backgrounds, and years of experience. The participants consisted of 55.6% males and 44.4% females, reflecting a relatively balanced gender distribution. The age distribution was as follows: The majority were in the 41 - 50 years age group (38.9%), followed by the 30 - 40 years group (33.3%) and the 51 - 60 years group (27.8%).

In terms of educational background, 50.0% of participants held a master’s degree, 27.8% had a PhD, and 22.2% held a Bachelor’s degree. Regarding professional experience, 50.0% had between 11 - 20 years of experience, 27.8% had between 5 - 10 years, and 22.2% had 21 - 35 years of experience in their respective fields.

Participants came from various professional backgrounds, with the largest group working in public health and policy (38.9%), followed by healthcare management (33.3%) and social/community work (27.8%, Table 1).

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 32 (55.2) |

| Female | 26 (44.8) |

| Age (y) | |

| 30 - 40 | 19 (32.8) |

| 41 - 50 | 22 (37.9) |

| 51 - 60 | 17 (29.3) |

| Level of education | |

| Bachelor's degree | 13 (22.4) |

| Master's degree | 29 (50.0) |

| PhD | 16 (27.6) |

| Years of experience (y) | |

| 5 - 10 | 16 (27.6) |

| 11 - 20 | 29 (50.0) |

| 21 - 35 | 13 (22.4) |

| Field of work | |

| Healthcare management | 8 (13.8) |

| Public health and policy | 6 (10.3) |

| Social work/community engagement | 5 (8.6) |

| Homemaker | 6 (10.3) |

| Retired | 4 (6.9) |

| Education/teaching | 5 (8.6) |

| Market/bazaar worker | 5 (8.6) |

| Unemployed | 4 (6.9) |

| Student | 3 (5.2) |

| Labor worker | 2 (3.4) |

In this study, data saturation was reached after conducting 58 interviews, and qualitative analysis was subsequently carried out. The findings revealed a set of main concepts and sub-concepts regarding the role of kindness in community-based health promotion, explained from both scientific and practical perspectives. These concepts, integrating psychological, sociological, and public health research insights, illustrate the complex relationships between acts of kindness and their effects on individual and community health. Table 2 below presents and elaborates on these concepts in detail.

| Main and Sub-concepts | Sub-sub-concepts |

|---|---|

| Mental and emotional well-being | |

| Improving mental and emotional health | Reduced healthcare costs; increased productivity and economic contribution; improved social relationships and cohesion; lowered risk of social issues; enhanced resilience in times of crisis; promotion of preventive health; breakdown of stigma and promotion of mental health awareness |

| Increasing resilience and coping mechanisms | Better mental health and well-being; improved coping with stressful events; enhanced social support networks; promoting healthier lifestyle choices; improved recovery from adversity; reduced healthcare costs; fostering a culture of positive change |

| Social cohesion and community support | |

| Fostering social cohesion and support networks | Improved mental health through social connections; increased access to resources and assistance; reduction in social isolation; promotion of healthy behaviors; crisis response and community resilience; reduction in crime and social unrest; support for vulnerable populations |

| Reducing violence and conflict | Improved mental health; reduction in physical injuries and mortality; stronger social cohesion; promotion of healthy lifestyles; improved economic stability; fewer social disruptions and strain on public services; increased safety and reduced crime |

| Health promotion and public engagement | |

| Promoting altruism and public health initiatives | Enhanced access to healthcare and resources; encouragement of preventive health practices; strengthening social support networks; increased community engagement in health issues; reduction in health disparities; increased public health awareness and advocacy; promotion of health equity and collective responsibility |

| Improving physical health | Reduced healthcare costs; increased productivity and economic growth; improved mental health; prevention of chronic diseases; social and community engagement; enhanced lifespan and quality of life; healthier children and future generations |

| Social equity and inclusion | |

| Enhancing social equity and inclusion | Improved access to healthcare; reduction in health disparities; increased social determinants of health; stronger community cohesion and social capital; promoting mental health and reducing stress; better health behaviors; building resilient systems and long-term sustainability |

| Encouraging cultural competence | Fostering empathy and understanding; breaking down cultural barriers; promoting inclusive dialogue; cultural awareness in health systems; building trust across cultures |

In this study, the findings revealed that promoting kindness within the community can have a profound impact on various aspects of individuals’ social and emotional health. Four main concepts emerged: Mental and emotional well-being, social cohesion and community support, health promotion and public engagement, and social equity and inclusion. These core concepts collectively illustrate the multifaceted role of kindness in enhancing community health.

To further illustrate these findings, participant statements provide real-world insights into how kindness influences community health. These concepts, as derived from the interviews, reflect both the practical and theoretical understanding of kindness’s role. The explanations below are supported by participant perspectives, with demographic details provided in parentheses for context.

4.1. Mental and Emotional Well-being: Improving Mental and Emotional Health, Increasing Resilience and Coping Mechanisms

One participant emphasized the importance of kindness in improving mental health, stating, “Kindness creates a sense of belonging and emotional safety, which helps reduce stress and anxiety. It encourages people to feel supported, and that support helps them deal with difficult situations more effectively” (male, 41 - 50 years, master’s degree, 11 - 20 years of experience, healthcare management). Another participant added, “When kindness is present in everyday interactions, it creates a supportive atmosphere where people feel valued and understood. This emotional support significantly reduces feelings of loneliness and depression in the community” (female, 35 - 45 years, master’s degree, clinical psychology).

Another participant added, “When we show kindness to each other, we build resilience. It helps people handle life’s challenges better, because they know they are not alone in their struggles” (female, 30 - 40 years, PhD, 21 - 35 years of experience, public health and policy). This statement highlights the connection between kindness and the increased resilience and coping mechanisms individuals develop through social support.

The concept of Improving Mental and Emotional Health underscores how kindness enhances resilience and coping mechanisms, allowing individuals to better manage stress and life challenges. Participants consistently described how kindness fosters a sense of belonging and emotional safety, which acts as a buffer against stress and anxiety.

In this context, the connection between mental and emotional health and increasing resilience and coping mechanisms is clearly demonstrated. Participants emphasized that kindness builds resilience by providing social support, enabling individuals to cope better with challenges. This shows that kindness not only helps alleviate emotional strain but also promotes psychological well-being through supportive networks.

4.2. Social Cohesion and Community Support: Fostering Social Cohesion and Support Networks, Reducing Violence and Conflict

A participant with extensive experience in social work explained, “By promoting kindness, we create stronger social bonds within the community. It allows individuals to feel part of a larger group, and this sense of community reduces the likelihood of conflict and division” (male, 51 - 60 years, bachelor’s degree, 11 - 20 years of experience, social work). This reinforces the idea that kindness plays a central role in fostering social cohesion and support networks, ensuring that people feel connected and supported.

Another interviewee shared, “When we interact with compassion, it not only prevents violence but also helps in resolving existing conflicts peacefully. People start to understand each other better and approach differences with empathy” (female, 41 - 50 years, master’s degree, 11 - 20 years of experience, public health and policy). Similarly, another participant remarked, “In neighborhoods where kindness is common, there is a noticeable increase in community participation, whether in volunteer activities or local decision-making. This collective spirit improves the community’s ability to solve health problems together” (female, 40 - 50 years, bachelor’s degree, community health worker). Furthermore, “Kindness encourages reciprocity; when one person acts kindly, it inspires others to do the same, creating a network of mutual help that strengthens the social fabric” (male, 45 - 55 years, master’s degree, social work). “Kindness spreads. One small act can change the whole mood of the neighborhood” (Participant 33, male, 29).

The spread of kindness within a community strengthens social support networks and reduces violence and conflict. Participants noted that kindness helps create strong bonds within the community, reducing the likelihood of conflict and division. This demonstrates how kindness contributes to social cohesion and community support, ensuring people feel connected and supported.

Notably, statements about reducing violence and conflict reflect how kindness serves as a preventative factor in mitigating social unrest and conflicts. This aligns with Putnam’s social capital theory, which argues that community trust and cooperation are associated with better health outcomes. These insights are consistent with Putnam’s theory of social capital, which posits that community trust and cooperation are closely associated with improved health outcomes (30, 31).

4.3. Health Promotion and Public Engagement: Promoting Altruism and Public Health Initiatives, Improving Physical Health

From a public health perspective, one participant noted, “Kindness fosters a spirit of cooperation, which is vital for public health initiatives. When people are kind to one another, they’re more likely to participate in community health programs and adopt healthier behaviors” (male, 30 - 40 years, master’s degree, 11 - 20 years of experience, public health and policy). This aligns with the concept of promoting altruism and public health initiatives, where kindness drives collective action for the betterment of public health.

Another participant remarked, “Being kind not only affects mental health but also physical well-being. When individuals support one another, it promotes healthier lifestyles and better health outcomes overall” (female, 41 - 50 years, PhD, 21 - 35 years of experience, social work). Another participant explained, “When kindness motivates people to share health information and resources, it breaks down barriers to access and encourages early intervention for illnesses” (female, 30 - 40 years, PhD, public health education). Moreover, “Kindness is the glue that binds community members together in health campaigns. It fosters trust in healthcare providers and boosts attendance in preventive screenings and vaccination programs” (male, 55 - 65 years, master’s degree, health policy expert). “When someone helps you without expecting anything, you feel seen and valued. It gives you hope” (Participant 12, female, 45). These observations align with studies indicating that prosocial behavior correlates with improved cardiovascular and immune function (32-34).

The concept of Promoting Altruism and Public Health Initiatives emphasizes the importance of kindness in improving physical health and fostering collective efforts toward health goals. Participants highlighted how kindness drives participation in health programs and encourages healthier behaviors.

Here, the direct relationship between kindness and increased participation in public health initiatives and adoption of healthier lifestyles is evident. These findings align with existing studies showing that prosocial behaviors are linked to better cardiovascular and immune function.

4.4. Social Equity and Inclusion: Enhancing Social Equity and Inclusion, Encouraging Cultural Competence

A participant with experience in healthcare management stated, “Kindness ensures that everyone, regardless of their background, has an equal opportunity to participate in health programs. It promotes inclusivity and ensures that no one feels left out” (male, 41 - 50 years, master’s degree, 11 - 20 years of experience, healthcare management). This reflects the concept of enhancing social equity and inclusion, where kindness creates opportunities for all individuals to access the benefits of health promotion.

Lastly, a participant emphasized the importance of cultural competence, saying, “When people are kind, they are more likely to appreciate cultural differences. This appreciation leads to more inclusive and respectful environments, which is crucial for addressing the health needs of diverse communities” (female, 51 - 60 years, PhD, 21 - 35 years of experience, public health and policy). A further perspective added, “A culture of kindness ensures that marginalized groups feel seen and heard in health initiatives, which helps reduce health disparities and builds trust” (female, 48 - 58 years, master’s degree, health equity advocate). Another participant noted, “Kindness challenges prejudices and promotes empathy, which are essential for culturally sensitive healthcare that respects diverse beliefs and practices” (male, 42 - 52 years, PhD, medical anthropology). These testimonies reinforce the concept that kindness is integral to social justice and equity, echoing principles in public health ethics (35, 36).

Kindness enhances social inclusion and promotes cultural competence within diverse communities. Participants pointed out that kindness creates equal opportunities for everyone to participate in health programs, ensuring no one is left behind. These concepts demonstrate that kindness can act as a tool for breaking down prejudices and creating inclusive, respectful environments in health initiatives. Kindness fosters social justice and equity by helping marginalized groups feel seen and heard in health efforts, thereby reducing health disparities.

These statements from participants highlight how kindness, when integrated into community practices, can have a profound and far-reaching impact on mental and emotional well-being, social cohesion, health promotion, and social equity.

The core concepts and sub-concepts derived from this study clearly demonstrate that promoting kind behaviors can lead to improved mental health, stronger social cohesion, enhanced support networks, and ultimately, the promotion of public health and social justice within communities. The results provide a scientific foundation for the design and implementation of human-centered, compassionate community-based health programs.

Collectively, these themes, along with the perspectives shared by participants, emphasize that kindness is not just a moral virtue but a vital social determinant. It has the potential to enhance mental health, strengthen community bonds, encourage public participation in health initiatives, and advance social justice. By expanding kind behaviors, communities can build resilience, reduce conflict, and create environments conducive to holistic health improvements.

These findings provide a scientifically grounded framework that can guide the development and implementation of community-based health programs. Specifically, integrating kindness as a core value in health promotion strategies enhances their effectiveness by addressing psychological, social, and cultural dimensions of health in a comprehensive manner.

In conclusion, this study elucidates the profound and multifaceted effects of kindness on community health. Kindness enhances mental and emotional well-being, strengthens social cohesion, stimulates active involvement in health initiatives, and advances social equity and inclusion. The insights obtained from participants offer rich, context-specific evidence that can inform health policymakers, practitioners, and researchers in designing compassionate, human-centered public health interventions that are closely aligned with the needs of the community.

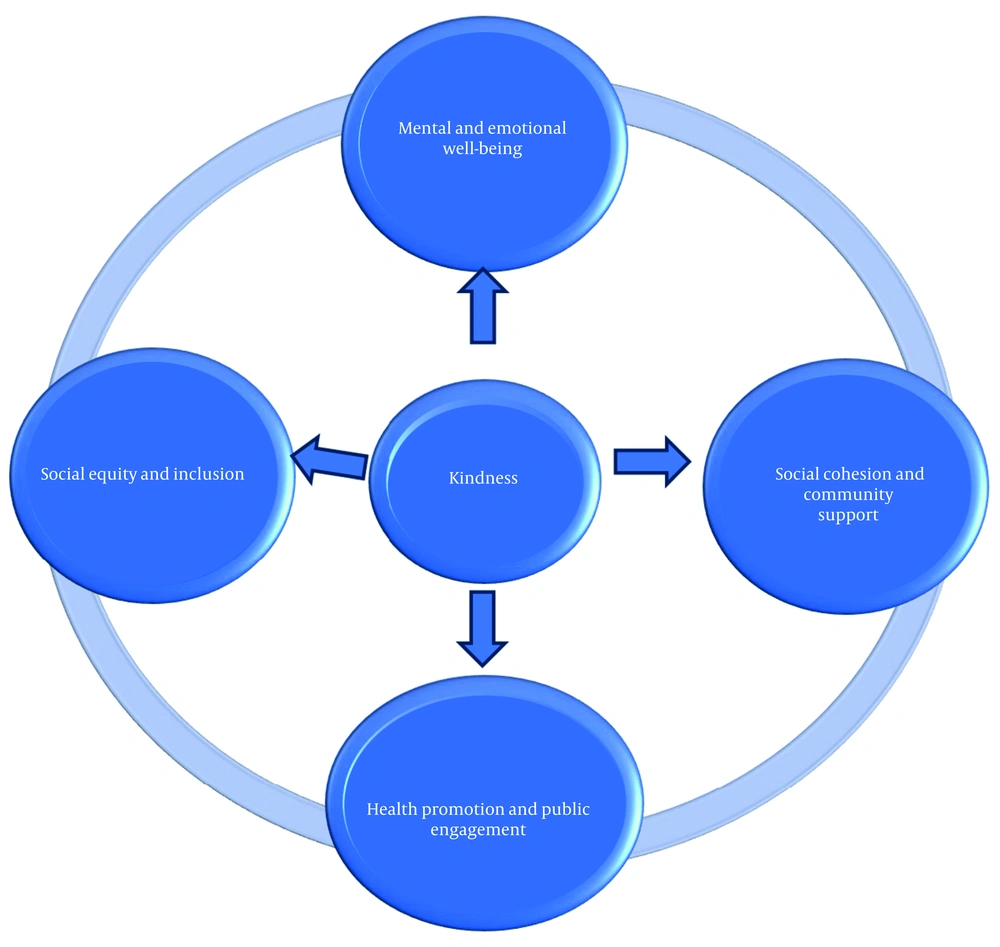

4.5. Conceptual Model: The Role of Kindness in Enhancing Community-Based Health

This conceptual model highlights the central role of kindness as a transformative social determinant that influences various dimensions of community health. Based on thematic analysis of qualitative data, kindness is framed not merely as a moral value but as a dynamic mechanism that drives engagement, equity, and well-being within communities. The model illustrates how kindness functions as an integral, multifaceted element in improving community health outcomes. Figure 2 below depicts the conceptual model derived from this study.

In this model, the relationships between the different domains and the central core are depicted with arrows, emphasizing the interconnectedness and mutual reinforcement of the various dimensions of community health. The model is structured around four interrelated domains:

1. Mental and emotional well-being: Kindness fosters emotional safety, empathy, and interpersonal support. These emotional resources enhance individuals’ ability to manage stress, cope with adversity, and build psychological resilience. Participants described how even simple acts of kindness can alleviate feelings of isolation and emotional fatigue.

- Pathways: Emotional validation and psychological safety; reduced anxiety and emotional distress; improved resilience and adaptive coping.

2. Social cohesion and community support: Kindness contributes to the formation of trusting, cooperative relationships. By nurturing positive social interactions, kindness strengthens community bonds, expands support networks, and reduces social fragmentation. Participants emphasized how kindness-driven relationships deter violence and foster conflict resolution.

- Pathways: Strengthened interpersonal connections and mutual aid; community trust and collective identity; decreased aggression and improved conflict resolution.

3. Health promotion and public engagement: Kindness enhances prosocial motivation, encouraging individuals to engage in altruistic behaviors and participate in community health initiatives. It lowers social barriers and increases willingness to contribute to collective goals, including preventive health behaviors and civic participation.

- Pathways: Increased public trust in health systems and authorities; motivation to support others’ health and well-being; improved participation in health education and outreach.

4. Social equity and inclusion: Kindness underpins inclusive practices by promoting cultural humility, respect for diversity, and fairness in access to resources. It reduces stigmatization and fosters environments where all individuals — regardless of background — feel valued and supported. Participants noted that kindness often acted as a bridge between social groups.

- Pathways: Greater inclusion of marginalized groups; reduced health disparities; enhanced cultural competence among providers and stakeholders.

4.6. Interconnections Between Domains

These four domains are interdependent and often reinforce one another. For instance, emotional well-being enhances an individual’s capacity to engage socially; stronger community bonds encourage greater public health participation; and inclusive environments promote better mental health outcomes and resilience. Kindness operates not as a standalone factor, but as a cross-cutting catalyst that facilitates positive change across multiple levels of community health infrastructure.

4.7. Role of Kindness in Community Health

The expansion of kindness plays a profound and multifaceted role in promoting health and well-being at all levels — from individuals to communities and beyond. Kindness is not merely a moral or ethical virtue; it is a powerful social force with tangible benefits for public health. It enhances both physical and mental well-being, strengthens social bonds, reduces interpersonal and societal conflict, promotes social equity, and contributes to the development of more compassionate and resilient communities. When kindness becomes embedded as a core element of social culture, it has the potential to foster a healthier, more cohesive, and flourishing society.

4.8. Comparative Analysis with Existing Theories and Models

This model extends and refines existing theories of social health, community participation, and social cohesion. The findings align with theories such as social capital theory (Putnam, 2000) (31, 37, 38) and community-based participatory research (39, 40), which emphasize the importance of community engagement and trust in fostering health and well-being. However, this model differentiates itself by specifically highlighting the role of kindness as a unique, active agent in building social capital and cohesion, going beyond abstract notions of social support. For example, while theories of social support (Cohen and Wills, 1985) stress the importance of supportive relationships, this model emphasizes how kindness-driven actions directly contribute to the formation of those relationships and the well-being of the entire community (41, 42).

Moreover, unlike conventional public health models that may focus primarily on health behaviors or access to services, this model foregrounds the psychological and social benefits of kindness as essential components of health promotion. By incorporating the subjective experiences of participants in Tehran, it highlights the cultural specificity of kindness, particularly within the context of collectivist cultures where interpersonal relationships and community solidarity are foundational to social life. This aspect underscores the novelty of the model and its relevance to Iranian culture, where kindness, hospitality, and familial values are deeply embedded in social norms.

4.9. Why This Model Is Relevant to Tehran and Iranian Culture

This model’s emphasis on kindness as a central force in community health is especially relevant in the Tehran context, where societal challenges such as urbanization, socioeconomic disparities, and cultural fragmentation are prevalent. Kindness in this setting is not just an abstract ideal but a pragmatic and deeply embedded social practice, cultivated through shared values like family ties, collectivism, and religious compassion. By embedding kindness into community health interventions, this model proposes an approach that resonates with the cultural norms of Tehran and provides a contextually relevant solution to health disparities.

Furthermore, this model introduces a new framework for understanding how kindness can be institutionalized as a social determinant of health. Rather than focusing solely on individual behavior or policy changes, this conceptual model underscores the collective impact of everyday acts of kindness in creating more cohesive, supportive, and health-conscious communities. Its novelty lies in its ability to bridge the gap between cultural values and public health goals, offering a culturally responsive and actionable strategy for improving community health.

4.10. Implications for Community-Based Health Programs

This model provides a conceptual foundation for the design of community-based interventions that prioritize compassion, inclusivity, and collective engagement as central strategies for improving public health outcomes. By embedding kindness into the fabric of community health programs, these interventions can create more supportive environments, reduce social divisions, and contribute to the overall well-being of individuals and communities. This approach, which directly integrates kindness into health promotion, allows for greater cultural resonance and improved health outcomes through increased community involvement and social connectedness.

In summary, the conceptual model presented in this study highlights kindness as a critical social determinant of health, offering both theoretical insights and practical applications for improving community-based health. By connecting mental well-being, social cohesion, public engagement, and social equity, the model presents a holistic, culturally grounded approach that can be adapted and applied to urban settings like Tehran and beyond. Through further empirical testing, the model could serve as a valuable tool for shaping future health interventions that leverage the transformative power of kindness to build healthier, more resilient communities.

5. Discussion

This qualitative study aimed to explore the role of promoting kindness in enhancing community-based health within the specific cultural context of Tehran, Iran. The findings revealed that kindness can function as a multidimensional strategy for public health improvement, influencing four interconnected domains: Mental and emotional well-being, social cohesion and community support, health promotion and public engagement, and social equity and inclusion. This study offers a unique contribution by examining the role of kindness as a community health tool within Tehran’s sociocultural environment, an area less explored in the existing literature. Below, we discuss how these findings align with and differ from previous studies.

5.1. Mental and Emotional Well-being

This study found that kindness plays a central role in enhancing mental and emotional well-being, acting as a catalyst for community health improvement. Unlike prior studies that primarily focused on individual benefits, participants in this study consistently described kindness as a collective factor contributing to psychological stability, emotional resilience, and coping with daily stressors. In high-stress or underserved communities, kindness served as a low-cost mechanism for fostering mental health equity. This is a novel contribution, demonstrating that kindness, when promoted within a community, can create systemic support structures for mental health beyond individual interventions.

These findings align with a growing body of literature that highlights the biological and psychological impact of prosocial behaviors. Acts of kindness are linked to the release of serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin — neurotransmitters that promote emotional bonding, happiness, and stress reduction (11, 12, 21, 43). However, our study uniquely contextualizes these biochemical responses within the lived experiences of participants in Tehran, adding cultural depth to the existing research. Fryburg (7) and others have reported similar psychological benefits, but our study is one of the few to emphasize kindness as a community-driven, sustainable intervention supporting mental health at a larger societal level.

5.2. Social Cohesion and Community Support

In addition to its psychological benefits, kindness was found to be a powerful driver of social cohesion and community resilience. Participants described how acts of kindness fostered feelings of belonging, mutual respect, and solidarity — particularly in neighborhoods experiencing economic hardship or social fragmentation. This observation supports findings from Baldassarri and Abascal, who demonstrated that prosocial behaviors such as volunteering and mutual aid enhance social capital and reduce community division (44). Our study extends these findings by emphasizing that kindness also acts as a community-level tool to reduce social isolation, a key social determinant of health.

Participants emphasized that kindness reduced isolation by promoting inclusion and reciprocal support, thus enhancing social networks. These insights build on work by Theron et al., who noted the protective role of social support in improving mental health and cardiovascular outcomes (45). Our study uniquely links these findings to everyday, informal expressions of kindness, such as helping a neighbor or showing empathy, which can significantly enhance community-level resilience and public health.

Furthermore, the study corroborates the biological impact of social connection, confirming that kindness contributes to cardioprotective effects (lower blood pressure, reduced cortisol, and inflammation) — factors that lower the risk of chronic diseases like cardiovascular conditions and diabetes (6, 10, 46-48). These findings offer a holistic view of kindness as both a psychological and physiological mechanism for enhancing community health.

5.3. Health Promotion and Public Engagement

This study highlighted that promoting kindness positively influences health promotion and public engagement at the community level. Acts of kindness, such as volunteering and helping others, were linked to improved physical functioning, reduced systemic inflammation, and lower mortality rates (16). This confirms and extends prior research, particularly the work by Foy et al., which linked prosocial behaviors to better physical health and increased community participation in health programs (49).

Kindness also fosters a deep sense of belonging, motivating individuals to actively engage in health promotion initiatives. Our study further demonstrates how kindness inspires community-driven health projects, such as neighborhood cleanups and caregiving networks, which enhance mutual accountability and solidarity. This participatory aspect of kindness, which motivates collective action for health, is a novel insight compared to studies that focus only on individual-level health behaviors.

While earlier research emphasized the psychological and social benefits of volunteering and prosocial behavior, our study shows that kindness directly impacts public health by promoting collective health action — a significant departure from existing literature that primarily focuses on individual mental health benefits.

5.4. Social Equity and Inclusion

A key finding of this study was the critical role of kindness in promoting social equity and inclusion. Participants consistently emphasized that kindness fosters respect for diversity, empathy, and non-judgmental interactions, helping bridge divides in ethnically and economically diverse neighborhoods. Our study offers a unique contribution by illustrating how kindness is linked to fairer service delivery, particularly in healthcare settings, where kindness was reported to prioritize marginalized or vulnerable populations.

These findings are in line with the work of Cuadrado et al., who found that prosocial behavior can reduce social exclusion and promote inclusivity (50). However, our study further emphasizes kindness as a cultural and organizational value, shaping equitable practices and guiding inclusive behaviors across various sectors, including healthcare and community services. This is an innovative aspect of the research, showing that kindness does not just affect interpersonal relationships but can be institutionalized to reduce health disparities.

Additionally, kindness functioned as both a “social lubricant” and a “moral compass”, encouraging inclusive behavior across different cultural backgrounds. A significant innovation in this study is its attention to the biological and physiological effects of kindness, showing that kindness can improve sleep, reduce anxiety, and even lower blood pressure — effects that contribute to broader health equity outcomes. This multidimensional view of kindness as a social determinant of health is a new contribution to the field.

The cultural context of Tehran, where collectivism and religious compassion are central, is integral to understanding how kindness functions in this study. While Iranian society’s collectivist values enhance the applicability of kindness within this context, these findings may have limited generalizability to more individualistic or secular societies. Therefore, future research should explore how kindness operates across diverse cultural frameworks to assess its role and limitations as a universal health strategy.

Overall, this study contributes to the emerging view of kindness as a social determinant of health, offering a unique, culturally grounded perspective on how kindness functions as a community-driven, multidimensional resource for health improvement. It extends previous research by emphasizing kindness not only as a moral or psychological virtue but also as an actionable, biologically relevant public health tool.

We recommend that future research explore how kindness can be institutionalized at the policy level, particularly in healthcare design, public education, and urban development, especially in low-resource, high-stress environments where low-cost, culturally relevant interventions are most needed.

5.5. Conclusions

This qualitative study highlights the multidimensional and culturally grounded role of kindness as a strategic determinant of community-based health. Drawing on insights from 58 participants in Tehran, the study demonstrates that kindness operates across four interconnected domains — mental and emotional well-being, social cohesion and community support, health promotion and public engagement, and social equity and inclusion — each reinforcing the others to strengthen collective health outcomes.

Unlike prior research that has primarily conceptualized kindness as a moral or emotional construct, this study identifies it as a socially embedded and actionable health mechanism. Kindness was shown to enhance psychological resilience, foster trust and reciprocity, and mobilize collective participation in health-related behaviors. Participants consistently emphasized that both every day and organized acts of kindness reduced stress, built belonging, and encouraged civic engagement — findings that extend existing theories of social capital and collective efficacy into a new, culturally specific context.

Importantly, kindness emerged as a protective factor against anxiety, depression, and social alienation, aligning with growing biomedical evidence on its neurophysiological benefits (e.g., reduced cortisol and improved emotional regulation). Moreover, during periods of collective strain — such as public health crises or economic stress — kindness acted as a stabilizing and resilience-building force, enhancing social solidarity and mutual aid.

A distinctive contribution of this study lies in demonstrating how kindness functions as a culturally resonant public health strategy in Iranian society, where compassion and communal responsibility are deeply rooted in social and religious values. However, the use of purposive sampling in a single urban setting limits generalizability, and participants’ responses may reflect social desirability bias inherent in collectivist cultures. Future studies across diverse sociocultural contexts are therefore warranted.

From a policy perspective, the findings suggest that kindness should be institutionalized within health promotion frameworks — not merely as a moral ideal but as a measurable, actionable component of public health practice. Incorporating kindness into educational initiatives, community volunteering, and organizational health programs could strengthen social cohesion, reduce health disparities, and enhance community resilience, particularly in resource-constrained environments.

Ultimately, this study positions kindness as a low-cost, high-impact lever for advancing mental health, social justice, and collective well-being. In a global climate of rising stress and fragmentation, fostering kindness provides a practical, evidence-informed, and culturally adaptive approach to building healthier, more compassionate, and more equitable societies.

5.2. Limitations of the Study

This qualitative study has several inherent limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, as is typical in qualitative research, the relatively small sample size and purposive sampling approach limit the generalizability of results to broader populations. Although the study involved a diverse group of 58 participants, the findings are context-dependent and may not reflect experiences in other sociocultural or geographical settings.

Second, while qualitative methods such as interviews, focus groups, and observations offer in-depth insights, they also introduce potential biases. Participants may have been influenced by social desirability or cultural expectations, particularly given the strong religious and collectivist norms present in Iranian society. Similarly, researcher interpretation may introduce subjectivity. Although strategies such as data triangulation and member checking were employed to enhance credibility and trustworthiness, some residual bias is inevitable.

Third, the sample was composed primarily of experts and stakeholders affiliated with Iran University of Medical Sciences and the Ministry of Health, which may limit the applicability of findings to the general public or marginalized populations. Their perspectives — though valuable — may not fully capture the lived experiences of less privileged or underrepresented groups.

Fourth, the study’s cross-sectional design restricts causal inference. While associations between kindness and improved health outcomes were observed, causal directionality cannot be established. Longitudinal or mixed-methods research is needed to explore the evolving relationship between kindness and community health over time.

Fifth, the study’s contextual and cultural specificity must be acknowledged. The research was conducted in Tehran — an urban setting with distinct religious, cultural, and socioeconomic dynamics. Perceptions and expressions of kindness are deeply shaped by these contextual factors and may not be directly transferable to communities with different cultural orientations (e.g., individualistic or secular societies). Although cities were purposefully selected for their diversity in socioeconomic status and availability of community health programs, more culturally comparative studies are warranted.

Finally, time and resource constraints limited the depth and scope of data collection and analysis, particularly given the multifaceted nature of kindness as a social determinant of health. While efforts were made to extract meaningful insights from available data, a more prolonged engagement with participants could have yielded additional layers of understanding. Future research should consider larger samples, longitudinal follow-up, and cross-cultural comparisons to validate and extend these findings.

5.3. Suggestions for Future Research

Future research should explore the implementation and effectiveness of kindness-based interventions across diverse cultural and socioeconomic contexts to assess their sustainability and real-world impact. Particular attention should be given to marginalized and underserved populations, where kindness can serve as a low-cost, community-driven strategy for improving health equity.

Further studies should examine the biological, psychological, and social mechanisms linking kindness to health outcomes. Adopting mixed-methods approaches that integrate qualitative and quantitative data would enable a more comprehensive understanding of these pathways and clarify causal relationships between kindness, mental health, and social cohesion.

Expanding research to include larger and more diverse samples — across different ages, genders, and cultural backgrounds — will improve the generalizability of findings. In addition, targeted and longitudinal studies focusing on specific groups, such as adolescents, older adults, or vulnerable populations, can reveal how kindness interventions influence long-term well-being and community resilience.

Overall, these directions will deepen our understanding of kindness as a social determinant of health and inform evidence-based, culturally responsive policies that promote compassion, inclusivity, and collective well-being.