1. Background

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the leading cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for over a third of deaths in developed countries and approximately 50% in Iran (1-3). Among CVDs, coronary artery disease (CAD) is a prevalent condition and a major contributor to global mortality (4). Despite medical advancements, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that CAD prevalence has not declined, with annual deaths estimated to have reached 25 million by 2020 (5). In Iran, societal changes such as industrialization have made CAD a primary cause of death and a common non-communicable disease (6).

Timely diagnosis and effective treatment are crucial for reducing CAD-related mortality and complications (7). Coronary angiography remains the gold standard for diagnosing arterial stenosis, often facilitating simultaneous therapeutic interventions (8, 9). For severe blockages, two main interventional approaches are employed: Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and percutaneous coronary intervention (angioplasty). While angioplasty is less invasive, CABG is frequently necessary, particularly for patients with diffuse lesions, and remains a highly effective treatment (10, 11).

To enhance revascularization in patients with diffuse CAD, where CABG alone may yield suboptimal results, coronary endarterectomy (CE) has emerged as a valuable adjunctive technique (12-14). The CE, initially used to create suitable distal anastomosis sites, improves blood flow and is particularly beneficial in off-pump CABG for diffuse disease (15-18). Studies have shown promising outcomes, with some reporting high survival rates and no major adverse events after left anterior descending (LAD) endarterectomy via an off-pump method (19). Furthermore, off-pump endarterectomy is considered safe, feasible, and associated with better long-term graft patency compared to on-pump methods (20).

However, the definitive role of CE as an adjunct to CABG remains a subject of debate. While some studies suggest that CABG with CE is associated with lower mortality rates compared to CABG alone (12, 18, 21-24), others have indicated potentially higher mortality, though this may be influenced by underlying comorbidities (25). These conflicting findings are often attributed to varying patient population complexity, differences in surgical techniques, and the retrospective nature of many studies, which can introduce selection bias. Given that medical therapy is often less effective for severe coronary stenosis, surgical intervention, particularly with the potential benefits of CE, becomes critical. Given the increasing use of CE and the conflicting evidence regarding its outcomes, a comprehensive examination of its effects on patients is essential.

2. Objectives

In this retrospective study, we aimed to determine the safety and short-term clinical outcomes of adjunctive CE in patients with diffuse CAD who underwent CABG at Kosar Hospital, Semnan, from 2012 to 2021.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included all consecutive patients who underwent adjunctive CE with CABG at Kosar Hospital, Semnan, Iran, between March 2012 and March 2021 (Iranian calendar years 1391 - 1399). A census approach was adopted, including all eligible patients within the specified timeframe, thus negating the need for a formal sample size calculation.

3.2. Criteria

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Patients who underwent CE as an adjunct to CABG were included.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Patients were excluded if their medical records were incomplete or if essential data points for the analysis were missing. Patients who underwent concomitant cardiac procedures (e.g., valve surgery) were excluded to ensure a homogeneous cohort focused on the outcomes of CABG with adjunctive CE.

3.3. Data Collection

Patient medical records were comprehensively reviewed, and data were extracted into a pre-designed checklist. In cases of missing information, attempts were made to contact patients by phone to complete the data where possible. The collected information included: Demographic data (age, gender), comorbidities, pre- and post-operative blood biomarker levels, pre- and post-operative ejection fraction (EF), clinical course details (length of stay in the intensive care unit, number of grafts, involved coronary vessels), and postoperative outcomes (complications, in-hospital mortality). Postoperative complications were documented from patient records.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) was defined according to the KDIGO criteria, which includes any of the following: An increase in serum creatinine by ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours; an increase in serum creatinine to ≥ 1.5 times baseline within the prior 7 days; or a urine volume of < 0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 hours [Goyal, 2025 #69]. Dyspnea was documented based on new or worsening shortness of breath requiring increased respiratory support. Pulmonary edema was defined as clinical and radiological evidence of fluid accumulation in the lungs requiring diuretic therapy or increased respiratory support.

A limitation encountered was the absence of some post-operative blood biomarker measurements in patient records. For analysis, missing data points were not imputed; instead, comparisons were restricted to patients with complete pre- and post-operative data for each specific biomarker.

3.4. Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (version 22). Descriptive statistics were reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean ± SD for continuous variables. Comparisons of pre- and post-operative measurements were performed using paired t-tests or their non-parametric equivalents (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test), based on data distribution. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol received approval from the ethics committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences (ID: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1400.144). Patient confidentiality was strictly maintained throughout the study.

4. Results

This study included 50 patients who underwent coronary artery endarterectomy between 2012 and 2021. The mean ± SD age was 63.96 ± 9.35 years (range: 40 to 81 years), and 33 patients (66%) were male. The mean ± SD length of hospital stay was 147.12 ± 51.51 hours (range: 48 to 336 hours). The mean ± SD EF significantly decreased from 48% ± 8.77 preoperatively to 44% ± 9.28 postoperatively (P = 0.002). Among the patients, 28 had diabetes, 33 had hypertension (HTN), 12 had hyperlipidemia, and 15 had a history of ischemic heart disease, with some patients presenting with more than one comorbidity.

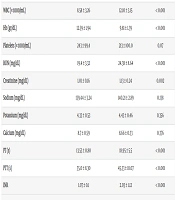

As shown in Table 1, significant changes were observed in several hematological and biochemical markers post-surgery. White blood cell (WBC) counts, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine levels, prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), and international normalized ratio (INR) all increased significantly postoperatively (P < 0.001 for WBC, BUN, PT, PTT, INR; P = 0.002 for creatinine). Conversely, hemoglobin (Hb) levels significantly decreased (P < 0.001). No significant changes were observed in platelet counts or sodium, potassium, or calcium levels.

| Markers | Before Surgery | After Surgery | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (× 1000/mL) | 8.58 ± 3.26 | 12.10 ± 3.15 | < 0.001 |

| Hb (gr/dL) | 12.59 ± 1.94 | 9.81 ± 1.39 | < 0.001 |

| Platelets (× 1000/mL) | 243 ± 99.4 | 213 ± 100.0 | 0.07 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 19.4 ± 3.32 | 24.38 ± 8.64 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.01 ± 0.16 | 1.13 ± 0.24 | 0.002 |

| Sodium (mg/dL) | 139.44 ± 3.24 | 140.21 ± 2.89 | 0.138 |

| Potassium (mg/dL) | 4.33 ± 0.53 | 4.43 ± 0.46 | 0.356 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 8.7 ± 0.59 | 8.66 ± 0.33 | 0.376 |

| PT (s) | 13.53 ± 0.80 | 18.95 ± 5.5 | < 0.001 |

| PTT (s) | 35.0 ± 8.30 | 45.33 ± 18.07 | < 0.001 |

| INR | 1.07 ± 0.1 | 2.03 ± 1.12 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; PT, prothrombin time; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; INR, international normalized ratio.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Paired t-test.

The majority of patients (46%) received four grafts, followed by three grafts (26%). As presented in Table 2, the LAD artery was the most common site for endarterectomy (44% of cases), followed by the right coronary artery (RCA, 40%).

| Vessel Site | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| RCA | 20 (40) |

| PDA | 14 (28) |

| PLV | 10 (20) |

| D1 | 3 (6) |

| D2 | 3 (6) |

| LAD | 22 (44) |

| LCX | 1 (2) |

| OM | 3 (6) |

Abbreviations: RCA, right coronary artery; PDA, posterior descending artery; PLV, posterior left ventricular branches; D, diagonal branches; LAD, left anterior descending; LCX, left circumflex artery; OM, obtuse marginal.

Table 3 summarizes the frequency of postoperative complications. The AKI was the most frequent complication (38%), followed by dyspnea (28%) and pulmonary edema (20%). The in-hospital mortality rate was 2%. Complications such as arrhythmia, re-intubation, tracheostomy, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and the need for dialysis were not observed in this cohort.

| Vessel Site | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Hemorrhage | 2 (4) |

| Dyspnea | 14 (28) |

| Arrhythmia | 0 (0) |

| Pulmonary edema | 10 (20) |

| Renal impairment | 19 (38) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 3 (6) |

| Need for balloon pump | 4 (8) |

| Re-intubation | 0 (0) |

| Tracheostomy | 0 (0) |

| CVA | 0 (0) |

| Need for dialysis | 0 (0) |

| AF | 2 (4) |

| RBBB | 6 (12) |

| Tamponade | 6 (12) |

| Chest pain | 8 (16) |

| Ventricular fibrillation | 1 (2) |

| Mortality | 1 (2) |

Abbreviations: CVA, cerebrovascular accident; AF, atrial fibrillation.

5. Discussion

This retrospective study analyzed the clinical outcomes of 50 patients who underwent CE as an adjunct to CABG at Kosar Hospital, Semnan, between 2012 and 2021. During this period, CE was performed in 3.84% (50 out of approximately 1300) of all CABG surgeries at our center. This incidence is lower than some reports, such as 11% by Livesay (26), potentially reflecting variations in surgical practices, patient selection, or the regional prevalence of diffuse CAD.

Our patient cohort frequently presented with HTN, affecting 66% of individuals. This is consistent with other studies by Sabzi et al. (27), Balaj et al. (28), and Alreshidan et al. (12), underscoring HTN as a common comorbidity in patients requiring coronary revascularization. Furthermore, the mean number of grafts used was 3.02, aligning with reports by Sabzi et al. (3.07) (27) and Ranjan et al. (3.3) (29). This suggests appropriate surgical decisions regarding the extent of revascularization for these complex cases. The LAD artery was the most frequently endarterectomized vessel (44%), which is consistent with Ranjan et al.'s findings (29), though Sabzi et al. reported a higher rate in the RCA (27).

We observed several expected physiological responses to cardiac surgery, including significant increases in WBC, BUN, creatinine, PT, PTT, and INR, alongside a significant decrease in Hb. These changes are largely attributable to the systemic inflammatory response, potential renal dysfunction, anticoagulation, and intraoperative blood loss. A notable finding was the significant decrease in EF post-operation (48% to 44%, P = 0.002). While a transient EF reduction is common post-cardiac surgery due to myocardial stunning, the statistical significance warrants further investigation into its long-term clinical implications and resolution.

The in-hospital mortality rate of 2% in our study is encouraging. Although a direct, unadjusted comparison to the general CABG population is scientifically inappropriate due to the higher-risk profile of CE patients, this low rate suggests that CE can be performed with acceptable short-term outcomes. Our finding is comparable to similar studies, such as the 1.9% reported by Ranjan et al. (29), and is notably lower than the 4.3% reported by Livesay (26). This supports the notion that with careful patient selection, adjunctive CE is a reliable procedure for managing diffuse CAD.

The mean length of hospital stay was 147.12 ± 51.51 hours. This duration appears longer than some reports (e.g., Ranjan et al.'s 36.6 ± 6.7 hours ICU stay) (29), primarily because, at our center, patients are directly discharged from the open-heart ICU. Thus, our reported "ICU stay" effectively represents the total "hospital stay".

The incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF) in our cohort was 4%, considerably lower than rates reported by GÜVenÇ et al. (37%) (30) and Ranjan et al. (15%) (29). This discrepancy could be influenced by variations in patient characteristics, surgical techniques, or postoperative protocols. The incidence of pleural effusion was 20%, which is lower than the 40% reported by Rossolatou et al. (31) but falls within the wide range (3.1% to 63%) reported in the literature (32-35).

Our most frequent complication was AKI at 38%. This high rate, defined by KDIGO criteria, highlights the vulnerability of this complex patient population to renal impairment post-surgery, likely exacerbated by baseline comorbidities. Dyspnea (28%) was the second most frequent complication. Overall, our findings suggest that adjunctive CE is associated with a low in-hospital mortality rate. Although the procedure carries expected risks for complex cardiac surgery, such as renal impairment and pulmonary edema, the outcomes support its viability as a treatment option for patients with diffuse CAD.

5.1. Conclusions

In our cohort, CE as an adjunct to CABG was associated with a low in-hospital mortality rate and a predictable profile of complications. While transient changes in biomarkers and events like bleeding occurred, these are often manageable consequences of complex cardiac surgery and necessary anticoagulation. Therefore, our findings support adjunctive CE as a viable and effective treatment strategy for patients with diffuse CAD. Based on these outcomes, CE can be considered a safe and effective method for treating CAD patients, particularly those with diffuse lesions.

To address the limitations of this study, we recommend larger, multi-center prospective studies with long-term follow-up. These studies should aim to further investigate the influence of comorbidities, the specific artery involved, and different surgical techniques on postoperative complications and long-term clinical outcomes.

5.2. Limitations

This study has several limitations inherent to its design. First, its retrospective nature may have led to incomplete data capture. Second, the small sample size (n = 50) limits the generalizability of our findings and the statistical power to detect smaller differences or rare complications. Furthermore, the single-center design may introduce selection bias related to our institution's specific practices and patient demographics. Finally, the lack of long-term follow-up data is a major limitation, preventing insights into the durability of revascularization and long-term survival. Future multi-center, prospective studies with larger cohorts and long-term follow-up are necessary to validate these findings and provide a more comprehensive understanding of this procedure's outcomes.

5.3. Implications for Health Policy, Practice, Research, and Medical Education

This study, conducted at Semnan's sole cardiac surgery center, offers crucial insights into the outcomes of CE combined with CABG. With a low in-hospital mortality rate (2%) and an acceptable complication profile, our findings affirm CE as a safe and effective revascularization strategy for diffuse CAD. This reinforces its continued use in clinical practice, particularly in cases where complete revascularization is otherwise challenging.

The observed longer hospital stays, directly linked to our center's practice of discharging patients from the ICU, highlight a need for tailored postoperative care pathways and efficient resource allocation in similar healthcare settings. This research underscores the importance of regional data in shaping health policy and medical education. It advocates for the continued provision of resources for CE services and suggests incorporating our real-world findings into medical training to better prepare professionals for managing these complex patients.

Furthermore, this study paves the way for future prospective, multi-center trials with larger cohorts to validate these outcomes, investigate long-term graft patency, and explore the impact of specific comorbidities, ultimately refining our understanding and improving patient care in cardiac surgery.