1. Background

Invasive candidiasis is a growing threat in contemporary healthcare, particularly affecting individuals with compromised immune defenses, including those undergoing chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies, recipients of solid-organ transplants, and patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) (1, 2). Over the past two decades, the incidence of candidemia, the most severe manifestation of invasive candidiasis, has increased by an estimated 50 - 70% in many tertiary care centers, reflecting both a broader at-risk population and advances in life-sustaining therapies that inadvertently predispose patients to opportunistic fungal infections (3, 4). Early diagnosis is critical; a delay in initiating appropriate antifungal therapy has been associated with increased attributable mortality (5).

Conventional blood culture techniques, while specific, are hampered by lengthy incubation periods that can exceed 72 hours before yielding definitive results (6, 7). False-negative cultures frequently occur in patients who have already received empirical antimicrobial agents or in those with transient or low-level fungemia (8, 9). Moreover, culture-based identification typically provides species-level resolution only after the initial growth phase, necessitating additional time for biochemical analysis (6). In practice, these delays translate into prolonged empiric therapy, potential overtreatment, and increased healthcare costs (10, 11).

The shifting epidemiology of Candida species in bloodstream infections (12-14) has led to the exploration of molecular detection techniques. Notably, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays targeting conserved fungal genomic regions offer the promise of overcoming the shortcomings of culture-based methods (15, 16). The PCR-based workflows can detect Candida DNA directly from whole blood or aliquots of positive culture media within hours (16). Several commercial and in-house PCR platforms have demonstrated sensitivities exceeding 90% and specificities near 100%; however, widespread adoption has been limited by factors such as high reagent costs, variable DNA extraction efficiencies, and the absence of standardized protocols across laboratories (17).

2. Objectives

The present study aimed to develop and validate an in-house PCR-based assay optimized for the rapid detection of Candida spp. directly from growth-positive blood culture bottles. To achieve this, we implemented an economical, high-yield DNA isolation protocol coupled with sensitive PCR amplification of the hyphal wall protein 1 (HWP1) gene, a well-validated, species-specific marker that provides robust discrimination among Candida species complexes (18). Finally, we performed a comparative analysis of this molecular workflow versus conventional blood culture identification in a cohort of 200 patients with suspected septicemia.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Ethical Considerations

A cross-sectional, laboratory-based study was conducted to detect Candida species in suspected positive blood culture samples. At least 10 - 24 hours had elapsed since their incubation at 35 - 37°C, and they exhibited macroscopic signs indicative of positive blood cultures, such as alarms from the BacT/ALERT system, hemolysis, turbidity, gas production, or formation of blood clots. With statistical consultation from the Statistical Consultation Center of Imam Reza Hospital in Mashhad, between November 2024 and March 2025, 200 blood culture vials exhibiting signs of positivity, namely turbidity, gas production, and/or hemolysis, were collected from patients presenting with suspected bloodstream infections at the Medical Microbiology Laboratory of tertiary hospitals in Mashhad (IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1404.026). Demographic data (age, sex, and underlying conditions) were recorded for downstream analysis.

3.2. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Two hundred (n = 200) positive blood culture vials, confirmed visually by the presence of turbidity, gas formation, or red blood cell lysis, and 20 negative controls were retrieved from conventional incubators or an automated incubator system (BacT/ALERT 3D, bioMérieux, France). A 500 µL aliquot of cultured blood from suspected positive blood culture vials was transferred into sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes and subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles: Rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen for 2 min, followed by thawing at 37°C for 12 min in a water bath. This thermal shock facilitates the mechanical disruption of the Candida spp. cell wall (19). Following the freeze-thaw step, lysis buffer containing 0.5% SDS and 20 µL proteinase K (20 mg/mL) was added to enhance the breakdown of host cells and protein contaminants. The mixture was incubated at 56°C for 30 min with intermittent mixing. Subsequently, 200 µL of 96% ethanol was added, and DNA was purified using a silica spin column protocol (Pars Toos DNA extraction kit, Iran), including two sequential wash steps and final elution in 50 µL of the elution buffer. DNA purity and concentration were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer, and samples were stored at -20°C until PCR amplification. Considering that a bacterial DNA extraction kit from Pars Tous, Mashhad, Iran, was utilized, the influence of potential PCR inhibitors (e.g., heme and proteins) from blood samples did not negatively affect the extracted DNA. Additionally, the beta-2-microglobulin gene was used as an internal control to verify the extraction and PCR processes.

3.3. Primer Design and In silico Validation

To amplify the HWP1 gene specific to the genus Candida, multiple sequence alignments were performed using BioEdit software (version 7.2.5; Tom Hall, Ibis Biosciences, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reference sequences for Candida albicans, C. glabrata, C. parapsilosis, C. tropicalis, and C. krusei were retrieved from GenBank. Conserved regions were identified, and primer pairs were manually designed to yield an amplicon size of 128 bp. The primer sequences were as follows: Forward primer (HWP1-F): 5′-CTGTTGTCACTGTTACTTCATGTTC-3′, reverse primer (HWP1-R): 5′-TGGAGTAGTTTCAGTTAATGGACAG-3′. Primer specificity was assessed using BLASTn (NCBI, Bethesda, MD, USA) against the non-redundant nucleotide database. Primers were deemed specific if no significant alignments to non-Candida genera were found (E-value < 1e-5, identity ≥ 90%, coverage ≥ 90%). Primers were synthesized by Metabion (Metabion International AG, Germany) and delivered in a lyophilized form. Upon receipt, each primer was reconstituted in nuclease-free water to a final concentration of 100 µM. Working solutions of 10 µM were prepared by serial dilution (1:10) in sterile distilled water and stored at -20°C.

3.4. Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity Testing

3.4.1. Specificity

To experimentally verify primer specificity, DNA was extracted from reference bacterial strains, including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterococcus faecalis, using the same protocol described above. The PCR was performed using each bacterial DNA as a template (100 ng per reaction) under standard cycling conditions. The absence of amplification confirmed microbiological specificity.

3.4.2. Sensitivity (Limit of Detection)

Genomic DNA from a reference C.albicans strain (ATCC 90028) was quantified spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop 2000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and serially diluted tenfold in nuclease-free water to yield concentrations ranging from 100 ng/µL to 1 fg/µL. Each dilution was tested in triplicate using PCR to determine the lowest concentration at which a visible band was observed by gel electrophoresis. The limit of detection (LOD) was defined as the lowest input DNA concentration yielding consistent amplification in ≥ two of three replicates.

3.5. Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification Protocol

The PCR reactions were assembled in a final volume of 25 µL each. Thermal cycling was performed on a Veriti 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, USA) under the following conditions: Initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 30 s, extension at 72°C for 45 s, and final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Each PCR run included positive controls (genomic DNA from C. albicans ATCC 90028) and negative controls (no-template control containing nuclease-free water instead of DNA) to monitor contamination and assay performance.

3.6. Gel Electrophoresis and Sequencing of Polymerase Chain Reaction Products

The PCR amplicons were resolved by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel alongside a 100 bp DNA ladder, yielding bands of ~128 bp. All PCR-positive samples were subjected to Sanger sequencing, and the sequence data were aligned against the NCBI BLAST database for species-level identification.

3.7. Data Compilation and Statistical Analysis

All amplification results were recorded as binary outcomes (positive or negative). Demographic and clinical parameters (age, sex, underlying diseases, and duration of hospitalization) were extracted from the laboratory records (Table 1). Data were entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Office 2019, Redmond, WA, USA) and subsequently imported into SPSS Statistics software (version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis. Prevalence estimation was calculated as the proportion of PCR-positive samples among all 200 samples tested, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) computed using the Wilson score method. Data visualization was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

| Sample ID | Blood Culture System | Culture Result | PCR Result (±) | Age (y) | Sex (M/F) | Underlying Condition (s) | Hospitalization Duration (d) | Sampling Prior Antimicrobial Therapy (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | BacT/ALERT | Candida spp. | + | 2.5 | F | Cancer | 21 | Y |

| 002 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 67 | M | ICU admission | 15 | Y |

| 003 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 79 | F | ICU admission | 5 | Y |

| 004 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 69 | M | ICU admission | 7 | Y |

| 005 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 52 | F | Burn unit | 18 | Y |

| 006 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 61 | F | Diabetes mellitus | 12 | Y |

| 007 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 64 | M | ICU admission | 10 | Y |

| 008 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 45 | F | Burn unit | 14 | Y |

| 009 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 70 | M | Cancer | 13 | Y |

| 010 | Conventional | Candida spp. | + | 59 | F | ICU admission | 11 | Y |

Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

3.8. Quality Control and Validation

To ensure reliability and reproducibility, the following quality control measures were implemented.

3.8.1. DNA Extraction Controls

For every batch of 24 samples, one extraction control (sterile water) was processed to monitor cross-contamination during DNA isolation. Extraction controls were subjected to subsequent PCR steps.

3.8.2. Negative and Positive Controls in Polymerase Chain Reaction

Each PCR run included at least one positive control (known C. albicans DNA) and one negative control without a template. The absence of amplification in the negative controls confirmed the integrity of the reagents.

3.8.3. Limit of Detection Determination

The reproducibility of the LOD experiments was confirmed by performing triplicate runs, and the lowest concentration detected in ≥ two replicates was accepted as the assay LOD.

3.8.4. Sequencing Confirmation

A subset of PCR-positive amplicons was sequenced to validate that the primers generated Candida-specific products. Sequence identities ≥ 98% to reference Candida species were considered confirmatory.

4. Results

4.1. Polymerase Chain Reaction Detection of Candida spp. in Blood Culture Samples

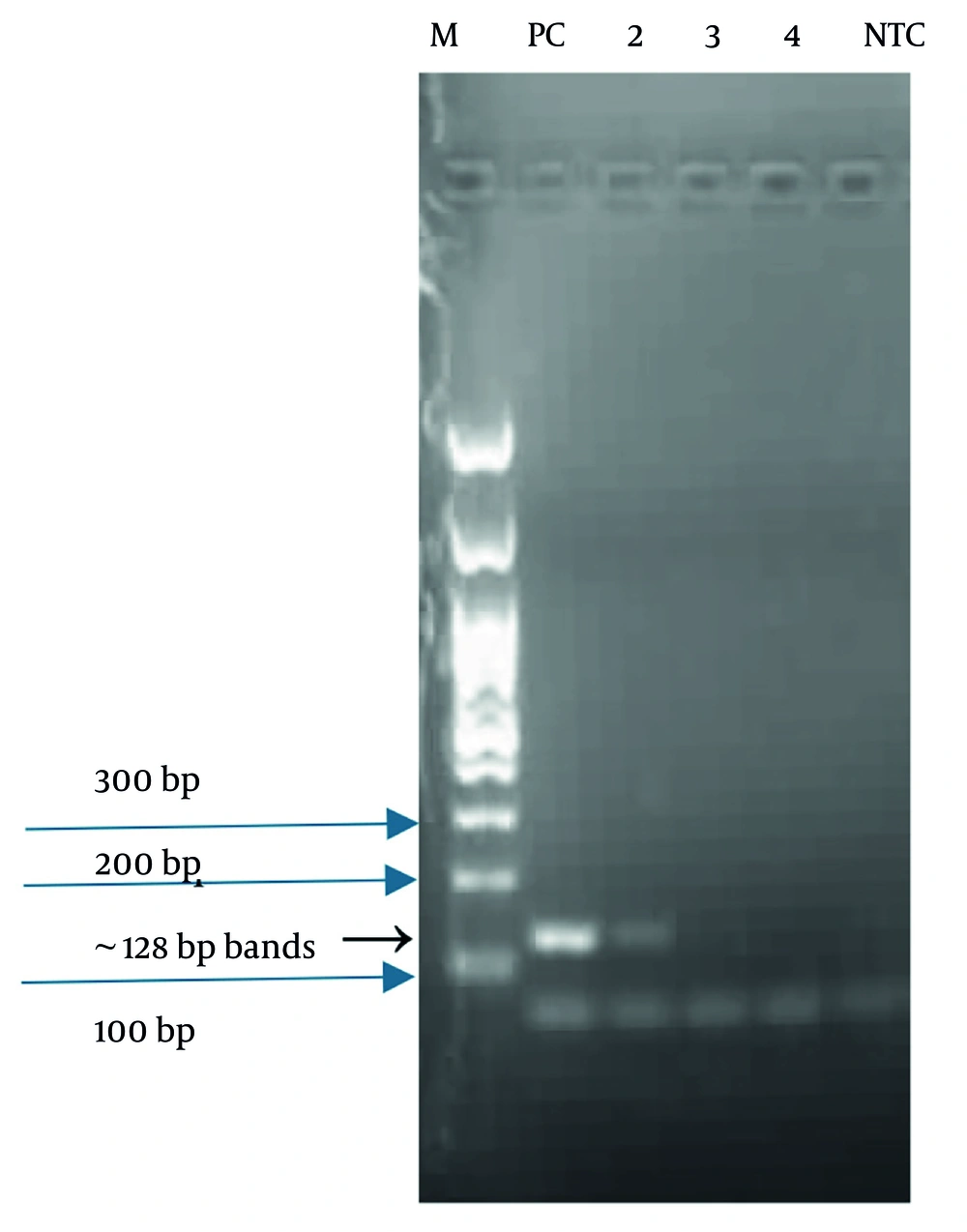

Of the 200 blood culture vials analyzed, 10 samples (5.0%; 95% CI: 2.7 - 9.0%) tested positive for Candida spp. using the in-house PCR assay targeting the HWP1 gene. The PCR products resolved on 1.5% agarose gels produced clear bands of ~128 bp, consistent with the expected amplicon size (Figure 1). All positive samples showed a single, distinct band without nonspecific amplification.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-amplified Candida hyphal wall protein 1 (HWP1) gene fragments. Lane M: 100 bp DNA ladder (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA); Lane 1: Positive control (Candida albicans ATCC 90028); Lane 2: Positive clinical sample exhibiting specific ~128 bp band); Lanes 3 and 4: Negative clinical samples without any specific band; Lane 5: No-template control (NTC), negative control.

4.2. Concordance with Conventional Culture Results

All PCR-positive samples (n = 10) were culture-positive for Candida spp. identified via conventional methods. No discordant cases (PCR-positive/culture-negative or PCR-negative/culture-positive) were observed among the tested samples. As mentioned in Table 2, the in-house HWP1-PCR assay demonstrated 10 true positives (TP), 190 true negatives (TN), and no false positives (FP = 0) or false negatives (FN = 0), resulting in 100% sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and overall diagnostic accuracy (200/200). These findings indicate perfect concordance between molecular and conventional phenotypic methods within this sample set. However, it is important to emphasize that such diagnostic performance metrics can be substantially influenced by the sample size and number of positive cases. Given the relatively low number of confirmed positive samples (n = 10), the calculated values may not fully reflect the real-world diagnostic variability. If the study population is expanded or the number of positive cases increases, the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values are likely to change, potentially yielding different interpretations. Therefore, while the current results are promising, large-scale validation is warranted to ensure the generalizability and robustness of the assay performance.

| Diagnostic Indicator | Value |

|---|---|

| TP | 10 |

| FP | 0 |

| TN | 190 |

| FN | 0 |

| Sensitivity | 100% (10/10) |

| Specificity | 100% (190/190) |

| PPV | 100% |

| NPV | 100% |

| Overall diagnostic accuracy | 100% (200/200) |

Abbreviations: TP, true-positives; FP, false-positives; TN, true-negatives; FN, false-negatives; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

4.3. Sanger Sequencing Confirmation

To validate the specificity of the PCR amplification, all PCR-positive samples were subjected to Sanger sequencing. BLAST analysis of the resulting sequences revealed ≥ 98% identity to reference sequences of C. albicans, confirming the taxonomic accuracy of the assay.

4.4. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

As reported in Table 3, of the 10 PCR-positive patients, 60% were female (n = 6), and the median age was 61 years (range: 2.5 - 79 years). The underlying conditions included ICU admission (n = 5), cancer (n = 2), diabetes mellitus (n = 1), and burn injuries (n = 2). The median hospitalization duration prior to sample collection was 13.5 days [interquartile range (IQR): 10 - 18]. The IQR of 10 - 18 days indicates that the middle 50% of PCR-positive patients had hospitalization durations between 10 and 18 days. This metric reflects the central spread of the data and reduces the influence of outliers. All patients received antifungal or broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy prior to sampling.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of PCR-positive patients | 10 |

| Mean age (y) | 57.6 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 4 (40) |

| Female | 6 (60) |

| Underlying conditions | |

| ICU admission | 5 (50) |

| Cancer | 2 (20) |

| Burn unit | 2 (20) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (10) |

| Mean hospitalization duration (d) | 13.6 |

| Median hospitalization duration | 13.5 (IQR: 10 - 18) |

| Prior antimicrobial therapy | 10 (100) |

Abbreviations: PCR, polymerase chain reaction; IQR, interquartile range.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

4.5. Statistical Analysis of Associated Risk Factors

Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests indicated no statistically significant association between Candida positivity and sex (P = 0.72) or underlying conditions when grouped by ICU-related vs. non-ICU admissions (P = 0.65). Continuous variables, such as age and hospitalization duration, were not normally distributed (Shapiro-Wilk P < 0.05); hence, Mann-Whitney U tests were applied. No significant difference in hospitalization duration was observed between the PCR-positive and PCR-negative groups (median 13.5 vs. 11 days, P = 0.41).

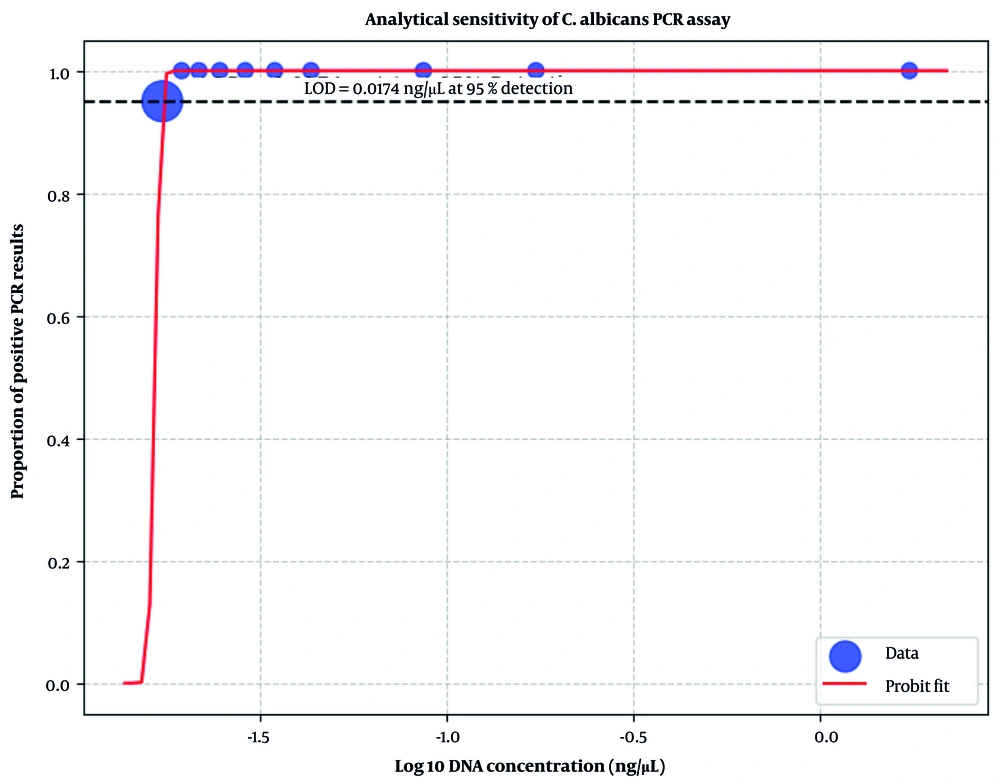

4.6. Assay Specificity and Analytical Sensitivity

No amplification was observed when the assay was performed on DNA from common bacterial species (E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, and E. faecalis), confirming the high microbiological specificity. Ten serial dilutions of C. albicans DNA (initial concentration: 1.74 ng/μL, final concentration: 0.0174 ng/μL at 1:100 dilution) were tested in triplicate. The LOD was the lowest concentration with positive amplification in ≥ 2/3 replicates. Confirmation involved 20 replicates at this concentration, requiring ≥ 95% positivity. Probit regression was used to model detection probability vs. log10(concentration) using statsmodels (Python v3.12), with binomial family and probit link, weighted by replicates. LOD95 was calculated as the concentration yielding a 95% detection probability. Analytical sensitivity testing established an LOD of 0.0174 ng/μL for C. albicans DNA, with positive PCR in all triplicates up to this dilution and 19/20 (95%) positive in confirmation replicates. Probit regression (β0 = 35.20, β1 = 19.07; deviance ≈ 0) confirmed the LOD95 at 0.0174 ng/μL (Figure 2), although the flat curve reflected a high detection efficiency across dilutions.

5. Discussion

The HWP1 gene encodes a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored protein located in the cell wall that is covalently linked to glucans (20). This gene is essential for hyphal development, adhesion to host cells — particularly through interactions with mammalian transglutaminases — and biofilm formation in C. albicans and closely related species (21). Its expression is predominantly confined to hyphal forms, which are frequently associated with active infections. Notably, the HWP1 gene displays considerable sequence polymorphism among various Candida species, especially within the C. albicans complex, which includes C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, and C. africana (22, 23). This polymorphism facilitates the differentiation of these closely related species based on variations in their amplicon size or sequence. Compared to the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions, which are commonly utilized for fungal identification, HWP1 may provide superior discrimination for specific species complexes (18). Although ITS regions are effective for general fungal identification, interspecies variation within certain Candida groups can be limited, suggesting that HWP1 could serve as a more precise tool in these instances (18).

The in-house HWP1-PCR assay identified Candida DNA in 10 of 200 (5.0%; 95% CI: 2.7 - 9.0%) growth-positive blood culture bottles, yielding complete concordance with the conventional phenotypic identification. The PCR assay for C. albicans achieved an LOD of 0.0174 ng/μL, as confirmed by probit regression with 19/20 positive replicates at this concentration (Figure 2). This sensitivity supports its utility in detecting low fungal loads in clinical samples. The most common Candida spp. reported by Dolatabadi et al. were C. parapsilosis (n = 58/160, 36%) and C. albicans (n = 52/160, 33%) in Mashhad candidemia cases in 2024 (24). In our study, sequencing data of all representative amplicons confirmed C. albicans in all sequenced samples. Arastehfar et al. observed a notable proportion of C. albicans (56/113; 49.5%), followed by C. glabrata (26/113; 23%) in Shiraz isolates (25). According to the aforementioned studies, our data did not detect non-albicans species, suggesting potential geographic or temporal shifts in regional epidemiology or a small number of positive cases in the study population.

While previous studies have leveraged multiplex real-time PCR panels to achieve rapid detection, our simpler, single-target HWP1 assay achieved equivalent sensitivity and specificity with reduced complexity and cost (26-30). By applying HWP1-PCR directly to growth-positive blood culture fluids, we reduced the time to species identification by over 48 hours compared to culture alone. This rapid turnaround extends the observations of Park et al., who reported similar time savings using a complex 9-plex panel, by demonstrating that a single amplicon, gel-based workflow can deliver comparable performance (31). Our 5.0% detection rate aligns with lower prevalence estimates from broader Iranian studies (32) but is lower than that of ICU-focused cohorts (25), likely reflecting differences in patient populations and prior antimicrobial therapy in our cohort.

This study validates an HWP1-targeted PCR assay as a cost-effective, high-resolution alternative to both traditional culture and multiplex platforms. Targeting the HWP1 gene, which is linked to hyphal wall dynamics and pathogenicity, provides robust species discrimination and may, in future work, correlate with virulence phenotypes (18). Practically, gel-based readouts require minimal infrastructure, making them especially suitable for resource-limited laboratories. The rapid and accurate identification of C. albicans in positive blood culture bottles has immediate implications for antimicrobial stewardship. Given that delayed appropriate therapy increases, the > 48-hour reduction in time to identification afforded by our assay could enable earlier de-escalation or escalation of antifungal regimens, thereby optimizing patient management and potentially improving outcomes.

5.1. Conclusions

In summary, the in-house HWP1-PCR assay demonstrated robust performance for the rapid identification of C. albicans directly from growth-positive blood culture bottles, achieving 100% sensitivity and specificity and reducing time to species determination by over 48 hours compared to conventional methods. By integrating an in-house, cost-effective, high-yield DNA extraction protocol with single-target PCR and gel-based readout, this approach offers a streamlined workflow that is readily implementable in resource-limited laboratories. The exclusive detection of C. albicans in our cohort aligns with regional epidemiological trends and underscores the reliability of the assay when applied to clinical specimens. Our results establish HWP1-PCR as a valuable adjunct to existing diagnostic paradigms and contribute to advances in the molecular detection of candidemia in patients with suspected septicemia.

5.2. Limitations

It is evident that this study did not investigate whether the C. albicans isolates were genetically identical or derived from diverse clades. Addressing this issue would require additional sequencing analyses at the DNA level, and examining the HWP1 gene alone is insufficient for such an assessment. Furthermore, this issue falls outside the scope of the present study. Detailed antifungal susceptibility and patient outcome data were not within the scope of this study; integrating minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) profiles and clinical endpoints in future studies would clarify the therapeutic impact of the assay. Our single-center design may limit generalizability to other regions of Iran; multicenter studies are needed to validate these findings across diverse settings. Finally, although no PCR inhibition was observed in this cohort, the direct application of the protocol to whole blood specimens may require additional steps for adaptation of the protocol for direct blood testing with optimized inhibitor-removal strategies.