1. Context

Thermal methodologies are commonly employed in the production of food items to ensure the creation of safe, edible products with extended shelf life and enhanced quality (1, 2). The utilization of frying, baking, toasting, roasting, and sterilization may yield both favorable and unfavorable consequences (3, 4). Some thermal procedures contribute to the generation of flavors and fragrances, as well as antimicrobial, antioxidant, and antiallergenic properties, and in vitro modulating activity (5-7).

Besides these favorable outcomes, it is crucial to carefully assess the generation of undesired by-products or sequences of thermal processing (8, 9). The loss of nutritional value, such as vitamins and essential amino acids during certain heat processing methods, is one of the main disadvantages (10-12). The most critical defect related to heated food is the formation of trace compounds during thermal processing at high temperatures or with long-term heating. These heat-formed contaminants are considered hazards due to their carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, and cytotoxicity. Major examples of such hazardous compounds include acrylamide, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), furan, heterocyclic aromatic amines (HAAs), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (13, 14).

Given the high occurrence of these heat-formed contaminants in food and insufficient knowledge and attitudes to prevent their formation, continuous monitoring and risk assessment are crucial to guarantee safety. The present study reviews recent findings regarding the formation, occurrence, toxicity, and analysis of major heat-formed contaminants in food.

2. Acrylamide

2.1. Formation and Occurrence of Acrylamide in Food

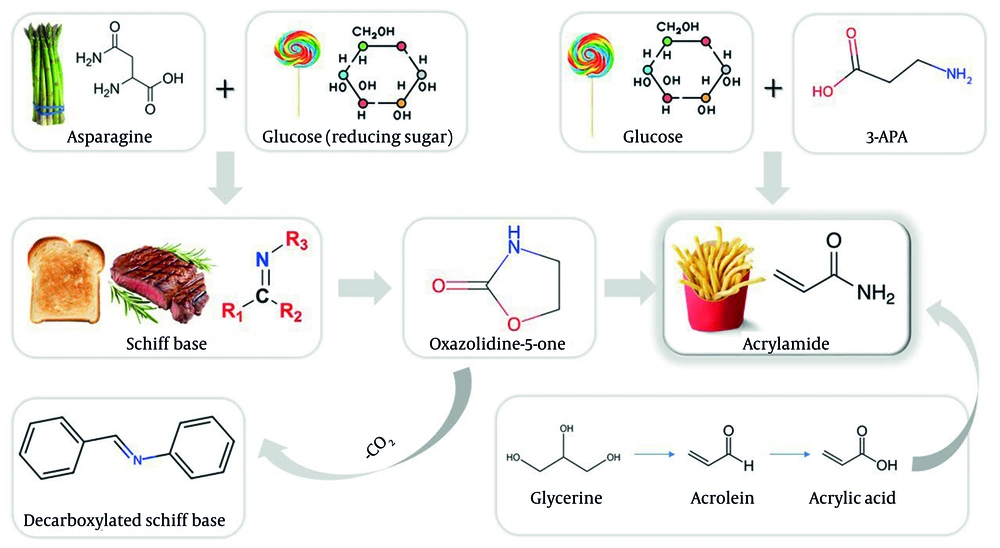

Acrylamide, an organic compound (CH2=CHC(O)NH2), can be formed by the hydration of acrylonitrile. This compound is generated in several heat-treated, carbohydrate-rich (starchy) foodstuffs, including bread, chips, potatoes, crisps, and coffee during high heat processing, above 120°C (248°F) (3, 15). Acrylamide formation occurs via a series of reactions between the amino acid asparagine and reducing sugars such as glucose. The Maillard reaction, in which free asparagine serves as the primary precursor, is the predominant pathway for acrylamide formation in foods following its detection therein (16, 17). Asparagine undergoes thermal decomposition, which proceeds via deamination and decarboxylation processes. However, the presence of a carbonyl source results in significantly elevated levels of acrylamide formation from asparagine (18). The occurrence of acrylamide is commonly reported in frequently ingested items like baked goods and deep-fried potatoes (French fries); other notable items include black olives, dried pears, dried plums, roasted barley tea, and peanuts (Figure 1). It should be noted that the formation of acrylamide is temperature-dependent, as it has not been reported in foods that have been boiled or in unheated foods (19, 20).

2.2. Toxicology and Dietary Exposure of Acrylamide

Since 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has classified acrylamide as a carcinogenic compound. Various studies have confirmed that acrylamide acts as a multi-organ carcinogen, inducing tumor formation in numerous organs, including the skin, uterus, mammary gland, lung, brain, and others (9). The assessment of acrylamide consumption through diet has been estimated for various populations across the globe. A significant range of diversity has been observed among populations with respect to their dietary practices and the methods employed in food preparation and handling (21). Dybing et al. posited a mean daily consumption for adults in close proximity to 0.5 mg/kg body mass (22, 23). The World Health Organization (WHO) approximates a daily dietary uptake of acrylamide of 0.3 - 2.0 mg/kg body mass for the general population, and up to 5.1 mg/kg body mass. The daily intakes of acrylamide in adults and children are estimated at an average of 1 and 4 mg/kg body weight, respectively. The larger consumption of specific acrylamide-containing foods, such as potato crisps and French fries, by children could be attributed to their higher calorie intake relative to body weight. Children tend to consume more acrylamide than adults (22, 24). Heudorf et al. (2009) conducted an evaluation of the dietary intake of acrylamide in children using a biomarker based on the mercapturic acids concentration in urine samples (25).

3. 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural

3.1. Formation and Occurrence of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural in Food

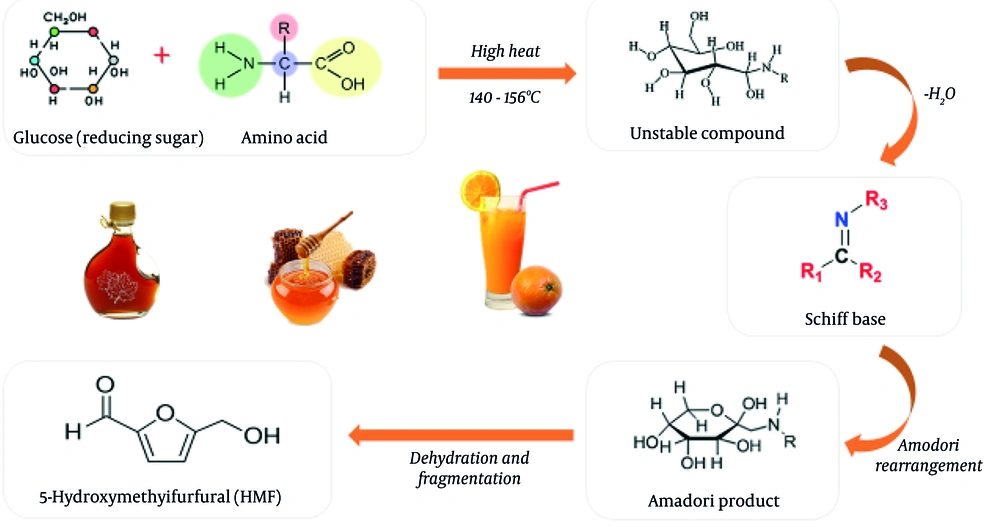

The HMF, a furanic compound named 5-(hydroxymethyl)furan-2-carbaldehyde or HMF, acts as an intermediary in diverse reactions. One such reaction is the Maillard reaction, while it can also be formed through caramelization, which occurs on sugars in acidic media and during thermal food processing (26). The procedure for the creation of HMF involves the identification of 3-deoxyosone as the principal intermediate. This intermediate arises from the 1,2-enolization and dehydration of glucose or fructose. Subsequently, the 3-deoxyosone undergoes additional dehydration and cyclization to produce HMF (Figure 2). Notably, HMF can be generated in acidic environments, and its content may notably increase at elevated temperatures during thermal treatments (27). The level of HMF present in foodstuffs is linked to the temperature used in carbohydrate-rich items, for instance, honey and caramel solutions. Notably, the concentrations of HMF in dried fruits and caramelized foods vary extensively and might surpass 1 g/kg. The HMF can also be generated in other foods, including malt, coffee, bakery products, vinegar, and fruit juices (28-30).

3.2. Toxicology and Dietary Exposure of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural

It has been observed that higher levels of HMF are related to irritation of the eyes, cytotoxicity, and afflictions of the respiratory system, skin problems, and mucous membranes. In rats, Ulbricht et al. have determined an LD₅₀ of 3.1 grams of HMF per kilogram body weight (31). In a distinct inquiry, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (1992) has approximated a lethal dose 50% (LD50) of 2.5 grams per kilogram for males and 2.5 - 5.0 grams per kilogram for females, in the case of acute oral exposure. The carcinogenic potential of HMF has been studied, indicating it could induce and elevate aberrant crypt foci (ACF, preneoplastic lesions) in rats’ colons (32, 33). Zhang et al. highlighted a significant dose-dependent elevation in ACF among rats subsequent to the ingestion of a sole dosage of HMF ranging from 0 - 300 mg/kg body weight (34).

Conversely, Surh et al. reported the emergence of skin papillomas via the administration of 10 - 25 mmol HMF to rats (35). The growth of lipomatous tumors in rats' kidneys via administration of HMF was stated by Schoenthal, Hard, and Gibbard in their research (36). The HMF has been recently identified as a carcinogen in multiple intestinal neoplasia in mice, resulting in progressive growth of adenomas. Additionally, in toxicology research based on a two-year gavage, it was found that HMF could result in rising hepatocellular adenomas in females (29, 32).

4. Furan

4.1. Formation and Occurrence of Furan in Food

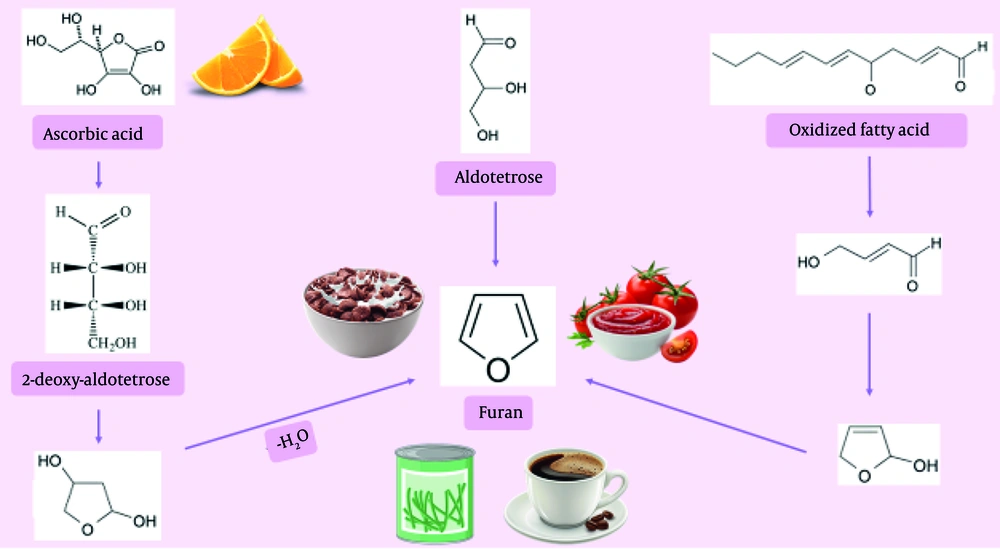

Furan (C4H4O) is a heterocyclic aromatic contaminant generated from multiple routes, including those involving sugars, unsaturated fatty acids, and ascorbic acid. The most prominent reaction is the Maillard reaction, which leads to non-enzymatic browning during food cooking and processing. Additionally, simple foods may generate substantial quantities of furanic components (37, 38). Perez Locas and Yaylayan (2004) conducted research on the genesis of furan in systems containing sugars processed at a temperature of 250°C (11). High levels of furan were observed during the thermal processing of ascorbic acid and dehydroascorbic acid. However, by heating amino acids and sugars alone, the generation of significant amounts of furan is precluded (Figure 3).

Certain investigations have indicated that roasting temperature and the quantity of unsaturated fatty acids are directly associated with the emergence of furan (39-41). Reports exist regarding furan occurrences in some heat-processed foods packaged in cans and jars. The results of an investigation disclosed data for 334 specific food items, many of which were frequently purchased baby foods and infant formulae, meat, seafood, coffee, nourishing beverages, pasta condiments, fruit conserves, and alcoholic beverages. The analytical approach utilized was limited by a quantification threshold of roughly 5 mg/kg, or parts per billion, for the majority of foods. The highest concentration of furan was detected in vegetables, specifically beans, sweet potatoes, and squash, which were packaged in jars or cans. Moreover, a substantial quantity of furan, varying from 20 to 200 mg/kg, has been recorded in unconventionally sealed food products, such as crackers, chips, loaves of bread, potato chips, and toasted bread (42, 43).

4.2. Toxicology and Dietary Exposure of Furan

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has stated that furan is evidently carcinogenic in both mice and rats. Additionally, the acquired data indicate that the carcinogenicity induced by furan may be attributed to a genotoxic mechanism (44). The assessment of furan's toxicity has revealed its remarkable capacity to induce carcinogenesis, with deleterious impacts on multiple bodily organs. The administration of low maximum doses of furan over a 13-week period resulted in weight loss, increased liver and kidney weights, decreased thymus weight, and toxic lesions in the liver and kidney of mice and rats, with severity increasing with dosage. Mortalities were observed in the rat species, with a larger percentage of males (90%) than females (40%) experiencing such incidences. However, no mortalities were noted among the mouse population, regardless of sex.

The administration of furan, at dosages of either 8 or 15 mg/kg body weight for a duration of 5 days per week over a course of 2 years, resulted in noteworthy weight loss at 15 mg/kg body weight and a significant increase in carcinomas and hepatocellular adenomas. Conversely, the implementation of higher maximum dosages (30 mg/kg furan via gavage 5 days per week) instigated cholangiocarcinoma of the liver in all 50 male rats. Furthermore, it was observed that 6 out of the total 40 rats subjected to furan dosage exhibited the presence of hepatocellular carcinomas after 9 months. Similarly, cholangiocarcinomas were found in all 10 male rats that continued to survive after 9 and 15 months (37, 45, 46).

5. Chloropropanols

5.1. Formation and Occurrence of Chloropropanols in Food

Chloropropanols, specifically 3-chloropropanediol (3-MCPD) and 2-chloropropanediol (2-MCPD), are contaminants that arise during the processing and production of specific food products due to the reaction between glycerol and hydrochloric acid. The process suggested for the formation of 3-MCPD and 2-MCPD is attributed to the interaction between hydrochloric acid and lipids. Specifically, the production of vegetable proteins and soy sauces by acid hydrolysis leads to the development of 3-MCPD and 1,3-dichloropropanol (1,3-DCP).

Research has demonstrated that various lipids, namely mono-, di-, and triacylglycerols, glycerol, triolein, and lecithin, possess the potential to function as precursors to the genesis of 3-MCPD and 2-MCPD following exposure to hydrochloric acid-induced heating. Additionally, investigations have disclosed that higher processing temperatures lead to the generation of these substances (47-49). Notifications regarding the presence of 2-MCPD in food were mostly confined to soy sauces and their corresponding products.

A monitoring study revealed that soy sauces contained 2-MCPD in quantities as high as 18 mg/kg, while other sauces contained up to approximately 9 mg/kg. In another study, significant amounts of both 2-MCPD and 3-MCPD were found across all tested samples of infant formulas. In China, an examination of soy sauces indicated that 2-MCPD was present in roughly 48% of samples (mean level of 0.01 mg/kg). A further survey revealed that the mean concentrations of 3-MCPD fatty acid esters in edible oils, fried foods, and baked confections were 0.862, 0.249, and 0.451 milligrams per kilogram, respectively (50, 51).

5.2. Toxicology and Dietary Exposure of Chloropropanols

Chloropropanols exhibit high gastrointestinal tract absorption rates and, at elevated doses, may elicit deleterious effects on the heart, liver, and kidneys. Nonetheless, a NOAEL dose of 2 mg/kg has been established for this compound (52). Limited records are available pertaining to the probable toxicity of these compounds. Nevertheless, various research has postulated that these substances possess the capacity to obstruct the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme, in addition to interfering with the glycolysis process. The development of 3-MCPD and 2-MCPD on the myocardium of rats has also been investigated, whereby it was found that cardiac muscle exhibited greater susceptibility to the toxicity of 3-MCPD. The aforementioned compounds have been observed to exhibit toxicity towards various other internal organs, with the kidney and testis being recognized as the primary organs targeted by the toxic effects of 3-MCPD (53, 54).

6. Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines

6.1. Formation and Occurrence of Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines in Food

The HAA are chemical compounds containing multi-ring aromatics with two different elements (one or more nitrogen atoms) and one amine group. The HAAs can be created during cooking (notably frying) of food items, especially meat, at high temperatures. The application of elevated temperatures for prolonged durations is crucial to the formation of HAAs. The non-polar group, which includes common pyridoindole or dipyridoimidazole moieties, is regularly allocated as pyrolysis yields of amino acids and is produced during thermal processing. The polar category, which includes the imidazoquinoxaline, imidazoquinoline, and imidazopyridine types, is produced from amino acids, carbohydrates, and creatinine at 150 to 250°C.

Recently, over 25 types of HAAs have been discovered and isolated in heated foods (55-57). Certain cooking methods have been correlated with decreased HAA formation; for instance, findings showed that the use of oven bags leads to a decrease in HAA content. Additionally, an investigation suggested that roasting meat at a temperature lower than 175°C and within 1.5 - 2 minutes resulted in lower levels of HAA. Furthermore, charcoal grilling methods resulted in the generation of higher levels of HAA compared to other cooking styles.

6.2. Toxicology and Dietary Exposure of Heterocyclic Aromatic Amines

The HAAs have been observed to display significant mutagenic and carcinogenic features. Humans are frequently exposed to these substances through both their diet and the environment. The IARC designates certain contaminants, namely 2-amino-3-methylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline (IQ), as a potential human carcinogen (class 2A), and 2-amino-3,4-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoline (MeIQ) and 2-amino-3,8-dimethylimidazo[4,5-f]quinoxaline (MeIQx) as possible human carcinogens (class 2B). An epidemiological inquiry revealed that HAAs may be linked to an elevated risk of breast, prostate, colorectal, pancreatic, and other cancers (58-62).

7. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

7.1. Formation and Occurrence of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Food

The PAHs are a significant type of environmental pollutant with aromatic rings consisting of five or six carbon atoms. Their formation takes place due to improper combustion of fossil fuels as well as during food processing, with smoked foods being the primary source of these compounds. It is noteworthy that raw foods, such as vegetables and fruits, can serve as a common source of PAHs, as they can absorb these compounds from soil, air, and water. The PAHs can also occur in foods through other processing methods such as drying, smoking, and packaging. Interestingly, some studies have reported the possibility of biodegrading PAHs in food by probiotic microorganisms, such as Bacillus velezensis and Lactobacillus brevis (14, 63-65).

7.2. Toxicology and Dietary Exposure of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons

It is noteworthy that PAHs are recognized as the most significant group of chemical carcinogens. As such, the European Scientific Committee on Food evaluated the risk posed by 33 PAHs on December 4, 2002. The committee concluded that 15 PAHs, including benzo[a]anthracene, benzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[j]fluoranthene, benzo[k]fluoranthene, benzo[a]pyrene, benzo[g,h,i]perylene, chrysene, cyclopenta[c,d]pyrene, dibenz[a,h]anthracene, dibenzo[a,e]pyrene, dibenzo[a,h]pyrene, dibenzo[a,i]pyrene, dibenzo[a,l]pyrene, indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene, and 5-methylchrysene, have clear genotoxicity (66-68).

Moreover, all these compounds, except benzo[g,h,i]perylene, are carcinogenic for animals. The committee also considered benzo[a]pyrene as a marker for the presence and effect of carcinogenic PAHs in food groups. Furthermore, on June 9, 2008, the EFSA approved an opinion titled "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Food”. In this opinion, the EFSA determined that benzo[a]pyrene is not a reliable marker for the existence of PAHs in food. Therefore, they recommended four compounds, namely, benzo[a]pyrene, chrysene, benzo[a]anthracene, and benzo[b]fluoranthene, as the most appropriate indicators of PAHs in food (69, 70).

8. Analysis Methods for Heat-Formed Contaminants

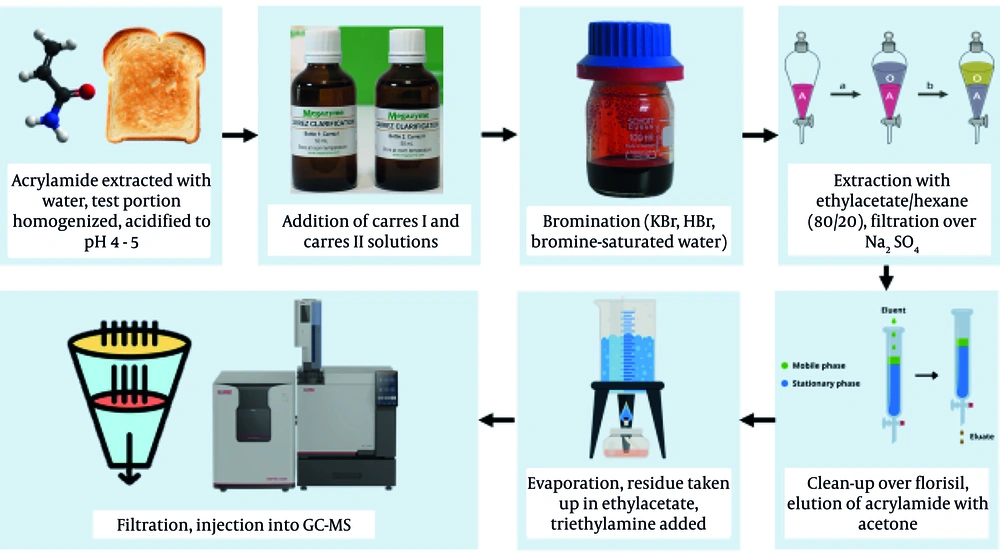

The most considered analysis methods and conditions used for quantification of heat-formed contaminants in food are listed in Table 1. It was observed that chromatographic methodologies are the most commonly considered techniques for the determination of trace concentrations of food contaminants such as heat-formed compounds (Figure 4). Owing to the intricate nature of food matrices and the concentration of acrylamide, HMF, furan, HAAs, and PAHs in processed or cooked foods, the methodologies used require particular clean-up conditions. The accurate detection and confirmation of trace amounts of these contaminants depend on precise preparation and separation procedures (71, 72).

| Analyte and Matrix | Sample Preparation | Separation Technique | LOD | LOQ | Recovery (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide | ||||||

| Dried fruits, edible seeds | QuEChERS | LC/MS | 2.0 µg/kg | 5.0 µg/kg | 61 - 82 | (73) |

| Bread | UAE-DLLME | GC-MS | 0.54 ng/g | 1.89 ng/g | 98 | (74) |

| Potato-based foods | HS-SPME | IMS | 4 ng/g | 10 ng/g | - | (75) |

| Bread, potato chips, cookie | SDME | GC-ECD | 0.6 µg/L | 2.0 µg/L | 97 - 104 | (76) |

| Fried food | DSPE | SERS | 2 μg/kg | 5 μg/kg | 73.4 - 92.8 | (77) |

| Fried food | DSMIPs–GO–Fe3O4 | HPLC-UV | - | - | 86.7 - 94.3 | (78) |

| HMF | ||||||

| Vinegar, soy sauce | UALLME | CE-UV | 0.03 mg/L | 0.10 mg/L | 1.24 - 109.39 | (79) |

| Fruit puree, juice | DLLME | HPLC-UV | 1.47 µg/L | 5.28 µg/L | 98.4 | (80) |

| Honey | HS-SPME | Polyoxometalate coated piezoelectric quart crystal | 3.4 µg/g | 11.4 µg/g | - | (81) |

| Furan | ||||||

| Baby food, fruit juice | HS-SPME | GC-FID | 0.001 - 0.00025 ng/mL | 0.005 - 0.0005 ng/mL | 92 - 103 | (82) |

| Fruit juices | HS-SPME | GC-FID | 0.056 - 0.23 ng/mL | 0.14 - 0.76 ng/mL | 90.2 - 110.1 | (83) |

| Baby foods | HS-LPME | GC-MS | 0.021 - 0.038 ng/g | 0.069 - 0.126 ng/g | 89.33 - 103.64 | (84) |

| Chloropropanols | ||||||

| Soy sauces | SPE | LC-MS, GC-MS | 0.01 mg/kg | 0.05 mg/kg | 85.09 - 98.88 | (85) |

| HAAs | ||||||

| Hamburger patties | MAE-DLLME | HPLC-UV | 0.06 - 0.21 ng/g | 0.15 - 0.70 ng/g-1 | 90 - 105 | (86) |

| Aqueous samples | DLLME-SFO | UPLC-MS/MS | 0.7 - 2.9 ng/mL | 2.2 - 8.7 ng/mL | 92 - 106 | (87) |

| Meat products | QuEChERS | HPLC-DAD-ESI-MS/MS | - | 0.005 - 0.1 ng/g | 56.51 - 113.97 | (88) |

| Roasted coffee | SPE | HPLC-FLD | 0.21 - 0.51 ng/g | 0.38 - 0.93 ng/g | 40 - 56 | (89) |

| PAHs | ||||||

| Smoked fish | MAE-DLLME | GC-MS | 0.11 - 0.48 ng/g | 0.36 - 1.6 ng/g | 82.1 - 105.5 | (90) |

| Coffee Samples | MAE-DLLME | GC-MS | 0.1 - 0.3 ng/g | 0.3 - 0.9 ng/g | 88.1 - 101.3 | (91) |

| Baby food | QuEChERS- LDS-DLLME | GC-MS | -0.3 μg/kg | 0.25-1 μg/kg | 72 - 106 | (92) |

| Water and milk | IT-SPME | HPLC-FLD | 0.017 - 0.23, 0.10 - 2.36 ng/L | 0.057 - 0.97, 0.33 - 7.78 ng/L | 78.5 – 118, 75.5 - 119 | (93) |

Abbreviations: HMF, 5-hydroxymethylfurfural; QuEChERS, quick, easy, cheap, effective, rugged, and safe; LC/MS, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; UAE-DLLME, ultrasound-assisted extraction-dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction; HS-SPME, headspace solid-phase microextraction; HAA, heterocyclic aromatic amin; PAH, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon; IMS, ion mobility spectrometry; SDME, single drop micro extraction; GC-ECD, gas chromatography-electron capture detector; DSPE, dispersive solid-phase extraction; SERS, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy; DSMIPs–GO–Fe3O4, dummy-surface molecularly imprinted polymers on a magnetic graphene oxide; GC-FID, gas chromatography-flame ionization detector; HS-LPME, headspace liquid-phase micro-extraction; MAE-DLLME, microwave-assisted extraction-dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction; DLLME-SFO, dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction with solidification of the floating organic droplets; UPLC-MS/MS, ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; MDES, magnetic deep eutectic solvent.

9. Food Safety Measures of Heat-Formed Contaminants

The Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) records information regarding safety issues associated with food and feed items. Data from the monitoring of products and recalls are proposed to protect public health. The contaminated products are notified based on contaminant type, country, and defined category of products. The implementation of protocols, data management, and efficient risk management is crucial for tracing and controlling food product safety. Table 2 provides information on recent food recalls of some major heat-formed contaminants alarmed by the RASFF during 2020 to 2024.

| Notifications and Category | Food type |

|---|---|

| Acrylamide | |

| Confectionery | Biscuits, waffle cups, oatmeal, cookies |

| Cereals and bakery products | Potato chips |

| Prepared dishes and snacks | Biscuits, corn waffle, rye flakes, crispy, extruded flatbread |

| Fruits and vegetables | Vegetable crisps, chips |

| Cocoa and cocoa preparations, coffee and tea | Instant coffee |

| Hydroxymethylfurfural | |

| Honey and royal jelly | Forest bee honey |

| Furan | |

| Prepared dishes and snacks | Baby-Food |

| Cocoa and cocoa preparations, coffee and tea | Roasted ground coffee |

| PAHs | |

| Cocoa and cocoa preparations, coffee and tea | Chocolates |

| Dietetic foods, food supplements and fortified foods | Ginseng extract, food supplement Spirulina |

| Fats and oils | Olive pomace oil. organic hemp oil, sunflower oil |

| Cereals and bakery products | Rice cakes for infants and young children, rice wafers, unripe wheat. roasted wheat (freekeh) baby chocolate biscuits |

| Fish and fish products | Smoked fish |

| Dietetic foods, food supplements and fortified foods | Valerian extract |

| Cocoa and cocoa preparations, coffee and tea | Chocolate powder, matcha tea powder |

| Herbs and spices | Dried green jalapeno pepper, lovage root ground, garam masala, organic paprika powder, white pepper, sliced organic wild garlic, ginger powder, cinnamon, dried bay leaves, and paprika powder |

Abbreviation: PAHs, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

10. Risk Assessments and Mitigation Strategies

The risk assessment of food contaminants is a multi-step process using toxicological and exposure data to protect public health (94). Human health risk assessments of contaminants in food involve the analysis of accurate content of hazardous compounds and the calculation of carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk in both adults and children (95, 96). Therefore, continuous monitoring of heat-formed contaminants in high-risk food items is necessary for estimating intake by individuals. On the other hand, the concentration of these trace contaminants in heat-processed food reflects the style of cooking and processing by producers or consumers. In terms of food security, hazard identification, hazard characterization, exposure assessment, and risk characterization are urgent (97, 98).

There are several practical strategies to mitigate the generation and occurrence of heat-formed contaminants in food. Mitigation strategies must be performed across the food supply chain, from agricultural practices to final cooking, to significantly reduce the formation of prominent contaminants such as acrylamide, furan, heterocyclic amines, and PAHs, as potential health concerns (99). Raw material supply is the primary step to control the composition of food materials. According to agronomical studies, the selection of potato and wheat varieties containing lower contents of free asparagine and reducing sugars (glucose, fructose) is considered the first acrylamide-reducing strategy.

Additionally, controlling the temperature (>8 °C) in sorting and storage of potatoes prevents the accumulation of reducing sugars (100). Some food preparation processes, such as meat marinating and the use of certain additives, can scavenge free radicals, which are precursors for the formation of some aromatic compounds. A key mitigation strategy is the reformulation and alteration of food recipes in both kitchens and industries. Also, controlling the two processing parameters of time and temperature is the most direct and effective factor in mitigating heat-formed contaminants in food (101-103).

Major helpful cooking practices include cooking carbohydrate-rich foods to a golden yellow, not a dark brown appearance, avoiding excessive frying and baking, using blanching or soaking for French fries or chips, using moist-heat methods (boiling, steaming, stewing), cooking before grilling, avoiding overheating of meat, and trimming and cleaning cooking equipment.

11. Conclusions

The application of thermal processes in food, particularly via the use of heat, possesses the capacity to give rise to the creation of perilous compounds, encompassing acrylamide, HMF, furan, HAAs, and PAHs. These process contaminants have the potential to be carcinogenic and exhibit acute or chronic toxicity. The formation of these contaminants can be influenced by factors such as the type of oil, refining conditions, and the presence of certain precursors. The concentrations of these contaminants in foods are typically low and may not pose a significant risk when consumed in moderation.

However, excessive consumption of specific foods or intensive heat treatment can increase the risk of exposure to these contaminants. The food industry and researchers continue to work on mitigating the formation of these process contaminants and lowering their levels in food products. Additional investigation is required to enhance comprehension regarding the formation, occurrence, and potential health risks associated with these process impurities in various food items.