1. Context

Viral hepatitis B and C (HBV, HCV) are significant global public health threats, with a global prevalence of approximately 4.1% and 3%, respectively (1, 2). While these viruses primarily cause liver damage that can lead to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), they are often asymptomatic, complicating efforts to control transmission. The burden is particularly high in developing countries (3, 4).

The transmission dynamics of HBV and HCV are complex and influenced by their genetic diversity. The HBV has at least ten genotypes (A-J), which vary geographically and impact disease progression; for instance, genotype C is associated with a higher risk of HCC compared to genotype B (5). Similarly, HCV has seven major genotypes and over 60 subtypes that affect disease progression and treatment response (6). Co-infection, particularly with other hepatitis viruses, further complicates treatment outcomes and therapeutic decision-making (7, 8).

While the primary transmission routes of viral hepatitis are well-established (e.g., blood transfusions, intravenous drug use), a large proportion of cases lack clear risk factors (4, 9). This has led to the hypothesis of non-blood-related transmission routes, such as sexual intercourse, mother-to-child, and intra-familial transmission (10-12). Although these routes are often considered inefficient, viral genomes have been found in various bodily fluids, including seminal and vaginal secretions, supporting the potential for non-parenteral spread (13, 14).

Despite this evidence, the role of blood-unrelated transmission, particularly within families, remains poorly quantified. Studies on this topic often lack a population-based cohort design, which has led to an underestimation of its significance (15, 16).

2. Objectives

The present systematic review and meta-analysis aim to fill this gap by assessing the role of horizontal transmission between family members in the spread of HBV and HCV.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Search Strategies

We conducted a systematic search of PubMed, ISI Web of Science, and Scopus from inception to August 2025 to identify studies on intra-familial hepatitis transmission. The search included terms such as "HBV", "Hepatitis B virus", "HCV", "Hepatitis C virus", "intra-familial transmission", "household transmission", and "transmission". Reference lists of relevant articles were also hand-searched. The search and selection process followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines and were performed independently by two reviewers.

3.2. Selection Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

1. Population: Household members of HBV- or HCV-infected index cases.

2. Exposure: Contact with an infected family member, either sexual or non-sexual.

3. Outcome: Reported prevalence or incidence of HBV or HCV infection among family members attributable to intra-familial transmission.

4. Study design: Observational studies (cross-sectional, case-control, cohort).

Exclusion criteria included review articles, case reports, editorials, studies on pathogens other than HBV/HCV, studies not reporting intra-familial transmission, duplicate publications, and in vitro/animal studies. No restrictions were applied regarding language or year of publication.

3.3. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The methodological quality of eligible studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which evaluates three domains: Selection (maximum 4 stars), comparability (maximum 2 stars), and outcome/exposure assessment (maximum 3 stars). Studies scoring ≥ 6 stars were considered high quality. In addition, potential sources of bias across studies (e.g., selection bias, misclassification of transmission route, and recall bias in self-reported exposures) were qualitatively assessed to provide context for the interpretation of findings.

3.4. Data Extraction

Data were independently extracted by two reviewers using a standardized form, including the following: First author, publication year, study country/region, study design, sample size, mean age, hepatitis type (HBV/HCV), definition of intra-familial transmission (sexual contacts vs. non-sexual household contacts), diagnostic methods, and reported transmission rates. Extracted data are summarized in Table 1.

| First Author | Year | Country | Design | Mean Age | Viral Infection | Sample Size | Non-sexual (%) | Sexual (%) | Diagnostic Test | QS | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portaleone et al. | 1983 | Italy | Cross-sectional | NA | HBV | 92 | 42.3 | NA | ELISA | 7 | (17) |

| Kotkat et al. | 1990 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | NA | HBV | 107 | 80 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (18) |

| Abdool Karim et al. | 1991 | Africa | Cohort | NA | HBV | 805 | 73.7 | 83 | ELISA | 9 | (19) |

| Wiercińska-Drapało et al. | 1991 | Poland | Cohort | NA | HBV | 394 | 8.6 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (20) |

| Wang | 1993 | China | Cross-sectional | NA | HBV | 109 | 24.8 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (21) |

| Comandini et al. | 1998 | Italy | Case-control | 54.3 | HCV | 365 | 5 | 9 | ELISA | 9 | (22) |

| Huet et al. | 2000 | French | Cross-sectional | NA | HCV | 52 | NA | 11.5 | ELISA | 7 | (23) |

| Brasil et al. | 2003 | Brazil | Cohort | NA | HBV | 355 | 23.6 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (24) |

| Ivanovski and Dimitriev | 2003 | Macedonia | Cohort | - | HBV | 2634 | 44.56 | 44.73 | ELISA | 9 | (25) |

| Akhtar and Moatter | 2004 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | NA | HCV | 427 | 20.5 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (26) |

| Barroso García et al. | 2004 | China | Cross-sectional | NA | HBV | 24 | 50 | NA | ELISA | 9 | (27) |

| Hajiani et al. | 2006 | Iran | Case-control | 40.5 | HCV | 360 | 1.33 | NA | Immunoblot assay | 6 | (28) |

| Ucmak et al. | 2007 | Turkey | Cross-sectional | 39 ± 11 | HBV | 454 | 30.5 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (29) |

| Akhtar and Moatter | 2007 | Pakistan | Cross-sectional | NA | HCV | 341 | 20.5 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (30) |

| AbdulQawi et al. | 2010 | Egypt | Cohort | 25.3 | HCV | 1224 | 2.29 | 5.47 | Molecular | 7 | (31) |

| Paez Jimenez et al. | 2010 | Egypt | Case-control | 36.1 | HCV | 778 | 40 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (32) |

| Ragheb et al. | 2012 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | 41 ± 10.7 | HBV | 230 | 12.2 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (33) |

| Mittal et al. | 2014 | India | Cross-sectional | 31.5 | HCV | 495 | 1.21 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (34) |

| Hatami et al. | 2013 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 36.3 | HBV | 454 | 24.2 | NA | ELISA | 6 | (35) |

| El Shazly et al. | 2014 | Egypt | Cross-sectional | 46.8 ± 10.1 | HCV | 50 | 4 | NA | Molecular | 9 | (36) |

| Sofian et al. | 2016 | Iran | Cross-sectional | 42.02 | HBV | 800 | 17.1 | 29.8 | ELISA | 7 | (37) |

| Gunardi et al. | 2016 | Italy | Cross-sectional | NA | HBV | 94 | 10.6 | NA | ELISA | 8 | (38) |

| Matsuo et al. | 2017 | Vietnam | Cross-sectional | 48 | HBV | 61 | 21.3 | NA | Molecular | 9 | (39) |

| Katoonizadeh et al. | 2018 | Iran | Cohort | 57.5 | HBV | 5388 | 8.3 | 2.2 | ELISA | - | (40) |

| Zhao et al. | 2021 | China | Cross-sectional | 41.6 | HBV | 1576 | 32.7 | 4.3 | ELISA | 9 | (41) |

Abbreviations: HBV, viral hepatitis B; HCV, viral hepatitis C.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

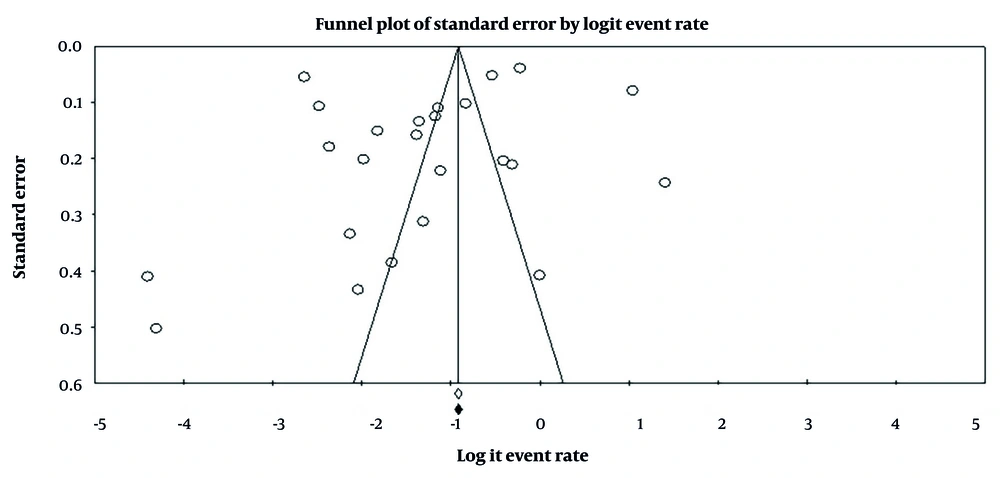

Meta-analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software (version 2.2; Biostat, Englewood, NJ). Pooled intra-familial transmission rates were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was assessed using the Cochrane Q test and the I2 statistic. Given the high heterogeneity (I2 values frequently > 90%), random-effects models were applied. To explore heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted by virus type (HBV vs. HCV), relationship type (sexual vs. non-sexual household contacts), geographic region, and study quality. Additionally, sensitivity analyses using the leave-one-out method were performed to assess the robustness of pooled estimates. Publication bias was evaluated using Begg’s and Egger’s tests, supported by funnel plot inspection.

4. Results

4.1. Literature Search

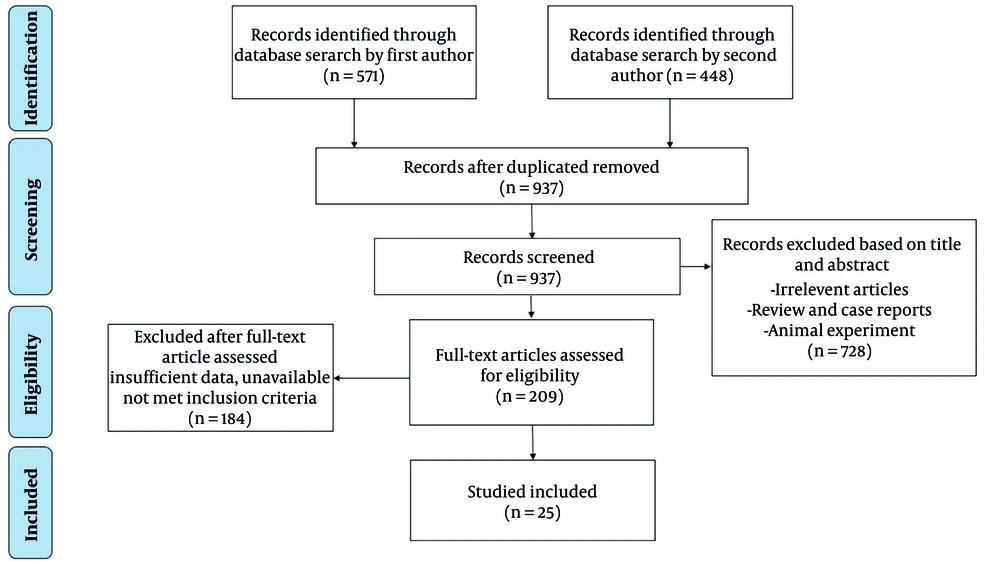

As shown in Figure 1, a total of 1,019 articles were identified through computer-assisted searches in ISI Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 997 articles were excluded. The primary reasons for exclusion were duplication, review articles, focus on pathogens other than HBV or HCV, lack of intra-familial transmission data, or absence of accessible full texts. After screening the reference lists of eligible articles, 3 additional studies were included, yielding 25 studies for systematic review and meta-analysis.

4.2. Study Characteristics

The main characteristics of the 25 eligible studies are summarized in Table 1 (12, 25-47). Overall, included studies were of moderate to high quality, with low to moderate risk of bias based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (Table 1). Studies were geographically diverse but predominantly from high-burden and tropical regions, including Italy (n = 3), Egypt (n = 5), Africa (n = 1), Poland (n = 1), China (n = 3), France (n = 1), Brazil (n = 1), Macedonia (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 2), Iran (n = 4), Turkey (n = 1), India (n = 1), and Vietnam (n = 1). Most were conducted in endemic settings. Publications spanned from 1983 to 2021, with 16 studies addressing HBV and 9 focusing on HCV. Regarding design, 17 studies were cross-sectional, six were cohort studies, and three were case-control studies. Viral hepatitis infection was diagnosed using ELISA, immunoblot assays, or molecular techniques. In total, 17,669 participants (mean age 41.5 ± 3 years) were included in analyses.

4.3. Pooled Prevalence of Intra-familial Transmission

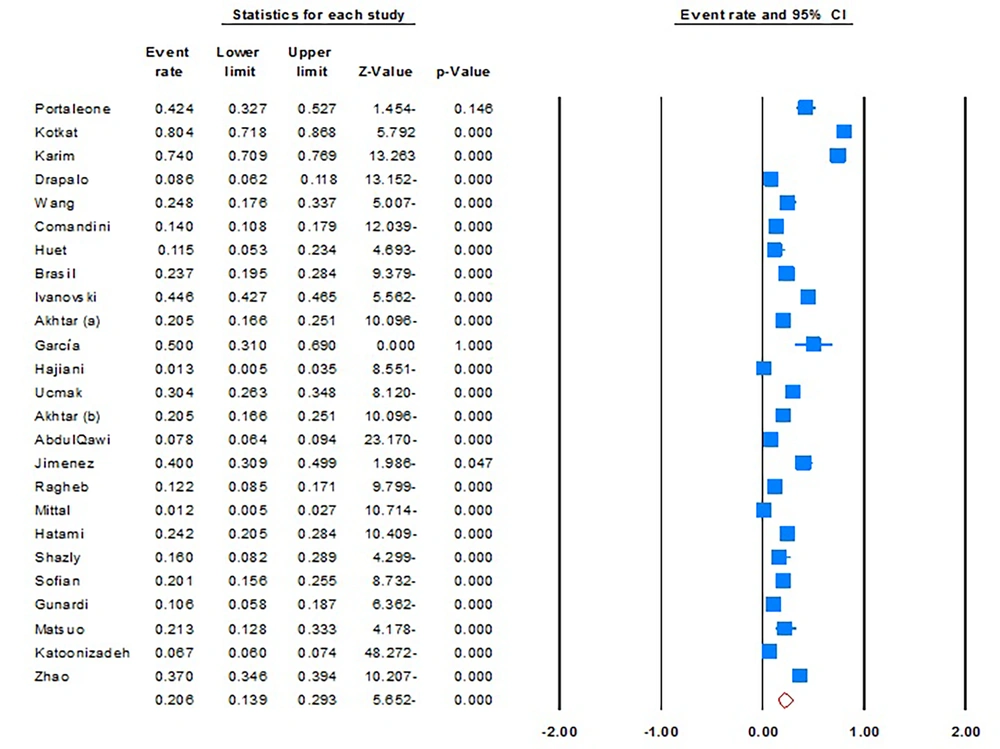

The pooled prevalence of intra-familial (sexual and non-sexual) transmission of viral hepatitis was 20.6% (95% CI, 13.9% - 29.3%; I2 = 99.0; P = 0.01; Begg’s P = 0.4; Egger’s P = 0.2) (Figure 2). Furthermore, sensitivity analyses revealed there is no significant difference with pooled estimates, suggesting the stability of the statistical analysis.

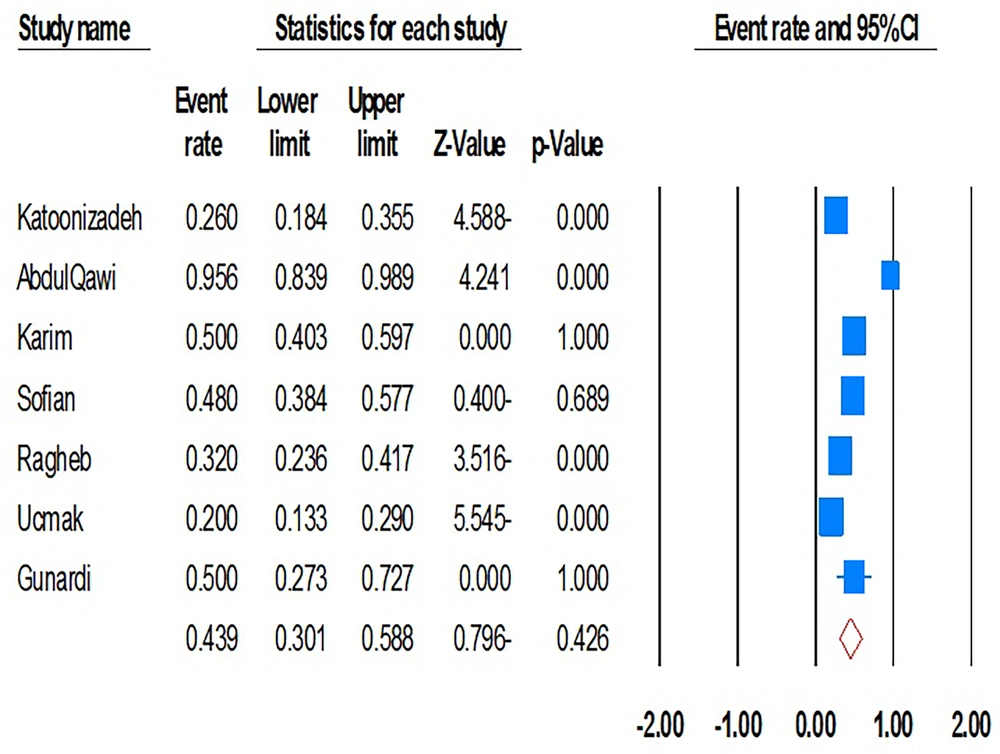

When stratified by virus type, the pooled prevalence of intra-familial HBV transmission was 28.6% (95% CI, 18.2% - 41.8%; I2 = 99.3; P = 0.01), while that for HCV was 10.8% (95% CI, 6.3% - 17.8%; I2 = 95.4; P = 0.01). In children from families with an HBV- or HCV-positive index case, pooled prevalence was 35.9% (95% CI, 16.3% - 61.7%; I2 = 99.7; P = 0.01) and 3.3% (95% CI, 1.6% - 7.0%; I2 = 84.9; P = 0.01), respectively. Notably, CIs for child HBV transmission were wide, reflecting heterogeneity and limiting precision of the estimate. Furthermore, mother-to-child transmission rates were also high, with a pooled prevalence of 43.9% (95% CI, 30.1% - 58.8%; I2 = 89.2; P = 0.01; Begg’s P = 0.5; Egger’s P = 0.7) (Figure 3). In this relation, although sensitivity analyses do not reduce heterogeneity, they approve the stability of original estimations.

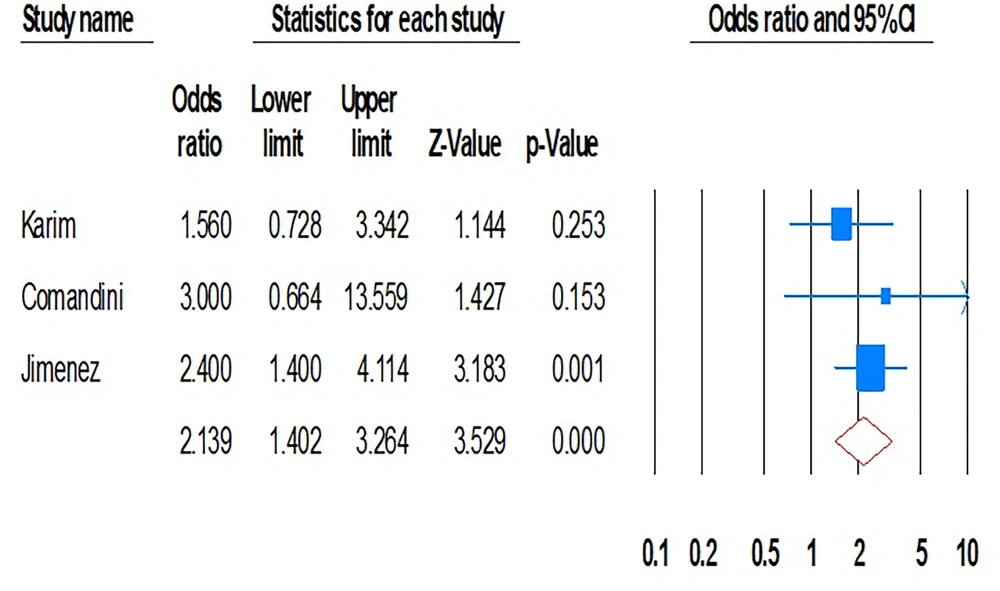

4.4. Frequency of Viral Hepatitis Transmission through Sexual Intercourse

The pooled estimates for viral hepatitis transmission through sexual intercourse were 15.3% (95% CI, 4.8% - 39.4%; I2 = 99.4; P = 0.01; Begg’s P = 0.2; Egger’s P = 0.1). Transmission rates of HBV and HCV between sexual household contacts were 21.5% (95% CI, 4.3% - 62.5%; I2 = 99.5; P = 0.01; Begg’s P = 0.8; Egger’s P = 0.3) and 7.7% (95% CI, 4.9% - 11.8%; I2 = 74.9; P = 0.01; Begg’s P = 0.9; Egger’s P = 0.4), respectively. Our data demonstrated that intra-familial transmission (both sexual and non-sexual) was significantly associated with viral hepatitis (OR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.4 - 3.2; P = 0.01; I2 = 0.00; P = 0.5; Begg’s P = 0.5; Egger’s P = 0.9) (Figure 4).

In this regard, the intra-household transmission of HBV and HCV infections was also significant (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 0.7 - 3.3; P = 0.01; I2 = 0.0; P = 0.8 and OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.4 - 4.0; P = 0.01; I2 = 0.0; P = 0.7). Furthermore, the included studies showed that sexual intercourse was a significant risk factor for both HBV and HCV infections among family partners (7 and 1). Our analysis indicated that the length of marriage significantly increased the risk of HCV infection transmission between household contacts with HCV-positive index cases (OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 0.72 - 5.28).

4.5. Subgroup Analyses

Subgroup analyses indicated substantial variability across regions, designs, and diagnostic methods (Table 2). Intra-familial transmission was higher in the Western hemisphere compared with the Eastern. Diagnostic method also influenced prevalence estimates: For HBV, ELISA-based studies showed higher prevalence (28.9%) than molecular studies (21.3%), while for HCV, molecular methods yielded higher prevalence (16.0%) compared to ELISA (6.1%).

| Items | HBV | HCV | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random-Effect Model | Heterogeneity | Random-Effect Model | Heterogeneity | |||

| % | 95% CI | I2 | % | 95% CI | I2 | |

| Geographical region | ||||||

| Eastern | 23.1 | 0.12 - 0.38 | 98.7 | 6.1 | 2.1 - 16.2 | 96.3 |

| Western | 32.8 | 20.2 - 48.5 | 98.7 | 10.0 | 2.0 - 37.2 | 98.0 |

| Design | ||||||

| Cross-sectional | 29.2 | 22.0 - 37.6 | 94.2 | 10.8 | 4.9 - 22.2 | 94.2 |

| Cohort | 26.5 | 9.1 - 56.3 | 99.7 | 2.3 | 1.6 - 3.3 | 0.0 |

| Case-control | NA | NA | NA | 7.4 | 0.9 - 41.7 | 97.8 |

| Diagnostic test | ||||||

| ELISA | 28.9 | 18.8 - 41.5 | 99.2 | 6.1 | 0.8 - 33.6 | 95.7 |

| Molecular | 21.3 | 12.8 - 33.3 | 0.0 | 16.0 | 8.2 - 28.9 | 0.0 |

Abbreviations: HBV, viral hepatitis B; HCV, viral hepatitis C.

4.6. Publication Bias

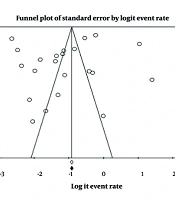

Begg’s and Egger’s tests did not reveal significant publication bias. However, visual inspection of the funnel plot indicated slight asymmetry, suggesting the potential for bias (Figure 5).

5. Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis consolidate available evidence on intra-familial transmission of HBV and HCV, pathways that remain less characterized compared to perinatal, parenteral, or healthcare-associated transmission. Given that perinatal transmission and intravenous drug abuse are considered major modes of transmission, estimating the precise rate of intra-familial spread is challenging (42).

Our results suggest that the overall horizontal transmission prevalence was 28.6% for HBV and 10.8% for HCV. In children from families with a positive viral hepatitis index case, the pooled estimates were 35.9% and 3.3%, respectively. This is consistent with previous studies that have reported a wide range of prevalence rates in children from endemic regions (12, 41, 42) and household contacts (36, 43). The inconsistency between our findings and those of previous studies may be explained by differences in sample size, study timeframes, intensity of contact, viral genotypes, and geographic locations. The majority of included studies were conducted in endemic and tropical regions, which may partly explain the elevated transmission rates and limit the generalizability of our findings to low-endemic or high-income countries.

Our results also highlight the critical role that mothers play in transmitting viral hepatitis to their children. Previous studies have shown that mothers, more so than fathers, can be central to the transmission chain (37, 44). Therefore, interrupting the mother-to-child transmission chain is a key strategy for prevention and control. The success of public vaccination programs, such as the one in Taiwan that reduced HBsAg seroprevalence from 9.8% to 1.3%, underscores the effectiveness of this approach. However, we were unable to assess several important factors influencing transmission, including viral genotypes, maternal viral load, age at exposure, comorbidities, and socioeconomic or cultural practices. These unmeasured variables likely contributed to the high heterogeneity observed and should be prioritized in future research.

Recent studies confirm a high burden of hepatitis infection among spouses and siblings of infected individuals. Our data showed that HBV and HCV infection rates among spouses of positive index cases were 21.5% and 7.7%, respectively. This is consistent with other studies that have reported a similar range of seropositivity (36, 45, 46). It is evident that marriage involves both sexual relations and close contact, which facilitates the transmission of HBV and HCV (42). The variability between studies may arise from factors such as lifestyle, vaccination status, and the duration of marriage, which has been shown to significantly increase the risk of HCV transmission between sexual partners (12, 36, 39, 43). Thus, considering the potential for transmission through sexual contact, implementing pre-marriage testing, screening of pregnant women, and vaccination of family members could significantly impede the transmission chain (46, 47).

A key limitation of this review is that many included studies predate the widespread use of modern therapies, such as direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for HCV (48, 49). The DAAs have been shown to markedly reduce viremia and transmission potential. Therefore, our estimates may reflect earlier transmission dynamics and likely overestimate current risks in settings where these therapies are widely accessible (50).

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the number of eligible studies was modest, and most were concentrated in developing regions. Second, the high heterogeneity limits the precision of our pooled estimates. Third, a lack of data on key variables prevented deeper stratified analyses. Fourth, the reliance on older studies may limit the relevance of our findings to current practices in the DAA era. Finally, the analysis was not pre-registered in PROSPERO. Despite these limitations, our findings highlight the importance of considering intra-familial exposure when designing HBV and HCV control strategies in high-burden settings. Given the heterogeneity and limited generalizability of the data, broad global recommendations cannot yet be made, and interventions should be tailored to local contexts.

5.1. Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate the significant role of intra-familial transmission in the spread of HBV and HCV infections. Our findings highlight the high prevalence of transmission through both sexual and non-sexual household contacts, particularly among children and spouses of infected individuals. Notably, mother-to-child transmission remains a critical route for HBV, while horizontal transmission, especially via sexual contact, is a key mode for both HBV and HCV. These results emphasize the urgent need for targeted public health strategies, including pre-marriage testing, screening of pregnant women, and vaccination of family members, to prevent and control intra-familial transmission. Further research should focus on large-scale, population-based studies to explore the underlying factors contributing to transmission in different regions and populations. Moreover, long-term studies are necessary to evaluate the impact of vaccination and screening programs in reducing transmission rates within families. Future efforts should also consider socio-behavioral dynamics, viral load, and duration of exposure as critical variables in understanding the transmission patterns of these viruses. By refining our understanding of intra-familial transmission and implementing effective prevention measures, we can significantly reduce the burden of HBV and HCV globally.