1. Introduction

Thailand is undergoing a significant demographic transition marked by a rapidly aging population. Older adults are disproportionately affected by non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and hyperlipidemia, which collectively account for over 71% of national mortality (1). Effective self-care and health-promoting behaviors are essential for minimizing complications, improving well-being, and reducing healthcare burdens in this group.

The Self-Rated Abilities for Health Practices (SRAHP) Scale, originally developed by Becker et al., measures individuals’ perceived self-efficacy in performing health-promoting behaviors across four key domains: “nutrition, stress management, physical activity, and health responsibility” (2). Grounded in Bandura’s Social-Cognitive Theory, the SRAHP conceptualizes self-efficacy as a central determinant of health behavior and outcomes, emphasizing individuals’ confidence in their ability to adopt and maintain healthy practices (3). The instrument has been widely adapted and validated across diverse cultural and clinical contexts, confirming its robust psychometric properties and broad applicability (4). For instance, self-care ability has been shown to influence health-promoting behaviors in patients with cardiovascular disease (5). However, a culturally validated Thai version of the SRAHP specifically tailored for older adults with NCDs has not yet been developed.

In Thailand, studies have emphasized the role of self-efficacy in promoting healthy behaviors among older adults, particularly those with hypertension (6). However, the absence of a culturally adapted, psychometrically validated tool limits clinical assessment and intervention planning. A reliable instrument tailored to Thai cultural and healthcare contexts is crucial for enhancing self-care strategies and supporting chronic disease management among older adults.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to translate, culturally adapt, and evaluate the validity and reliability of the Thai version of the SRAHP Scale among community-dwelling older adults with NCDs in Thailand.

3. Methods

A cross-sectional methodological study was conducted between September and November 2022 to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Thai version of the SRAHP Scale among older adults with NCDs residing in community settings across Thailand (7).

A total of 250 community-dwelling older adults (≥ 60 years) were recruited through multistage cluster sampling from one urban municipality and two rural subdistricts in Ubon Ratchathani Province, with proportional allocation across sites. Participants were eligible if they were ≥ 60 years old, had a clinician-confirmed NCD (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or cardiovascular disease), and had been diagnosed or actively managed within the past six months. Individuals were excluded if they had cognitive impairment (screened using the Abbreviated Mental Test Score < 8/10), severe acute illness, recent hospitalization within the past month, or were unable to communicate in Thai. Sample size requirements for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were based on the recommendation of 5 - 10 participants per item (8). With 28 items in the SRAHP, a minimum of 140–280 participants was required; thus, 250 participants were deemed adequate. To examine temporal stability, a sub-sample of 30 participants was randomly selected to complete the Thai SRAHP again after a two-week interval.

Health-Promoting Behaviors Scale (HPBS), developed by the Thai Health Education Division (9), includes 19 items across seven domains: nutrition, physical activity, smoking, alcohol use, stress management, rational drug use, and COVID-19 prevention. Items are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = completely), with higher scores indicating better health-promoting behaviors. Scores are classified as poor (< 60%), fair (60 - 69%), good (70 - 80%), or very good (> 80%) (9). The Cronbach’s alpha in this study was 0.75.

The SRAHP Scale, developed by Becker et al. (2), measures perceived ability to perform health-promoting behaviors in four domains: nutrition, stress management, physical activity, and health responsibility. It comprises 28 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = cannot do at all to 4 = do regularly), yielding total scores from 0 to 112 (low = 0 - 37, moderate = 38 - 74, high = 75 - 112) (2).

The SRAHP was translated into Thai following Beaton et al. (10) guidelines, including forward translation by two bilingual health professionals, back-translation by two independent translators, and expert panel review. A five-member expert panel (two public-health nurses, one gerontologist, one behavioral scientist, and one primary-care physician) evaluated the relevance of each item on a 4-point scale. The Item-Level CVI (I-CVI) was calculated as the proportion of experts rating the item as 3 or 4, and the Scale-Level CVI/Average (S-CVI/Ave) was computed as the average of all I-CVI values. This process followed standard CVI calculation procedures. Minor cultural adaptations were made to improve clarity, such as rephrasing ‘exercise’ as ‘regular physical activity’ and clarifying ‘rational drug use’ as ‘appropriate use of prescribed and over-the-counter medications.’ No substantive content changes were required. Cognitive interviews with older adults confirmed that all items were understandable and culturally acceptable. Pilot testing with 30 older adults with NCDs confirmed comprehension and cultural relevance, resulting in the final Thai version for psychometric evaluation.

Data were gathered through face-to-face structured interviews administered by trained research assistants to minimize literacy bias. Each interview lasted approximately 30 - 45 minutes and included both the Thai SRAHP and a demographic questionnaire.

Criterion validity was assessed by examining the correlation between the total Thai SRAHP score and participants’ self-reported health-promoting behaviors. We selected the HPBS as the external criterion because it is the nationally used health-promotion benchmark issued by Thailand’s Health Education Division (9). Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated, with r ≥ 0.50 interpreted as a strong positive relationship. Test–retest reliability was evaluated using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) based on a two-way mixed-effects model for absolute agreement. An ICC ≥ 0.75 was considered indicative of good reliability. As the SRAHP’s four-factor model is theoretically established, exploratory factor analysis was not conducted; CFA was used to verify model fit. Construct validity was assessed through CFA using maximum likelihood estimation in AMOS version 24. Model fit was evaluated using the following indices: χ²/df ≤ 3.0, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.90, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) ≥ 0.90, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.08 (11). Internal consistency reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the total scale and each subscale. Composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were also calculated to assess convergent validity.

4. Results

A total of 250 older adults with NCDs participated in the study (mean age = 69.61 years, SD = 7.47; 63.60% female). The most common NCDs were high blood pressure (65.6%) and diabetes mellitus (36.8%). The test–retest reliability of the Thai SRAHP was excellent, with an ICC of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.85 - 0.93), demonstrating strong temporal stability. The S-CVI/Ave was 0.92, and all I-CVIs were above 0.80. No floor or ceiling effects were observed, with fewer than 20% of responses falling into the lowest or highest categories. Convergent validity was supported by high standardized factor loadings (0.80 - 0.95) and AVE > 0.50 for all subscales.

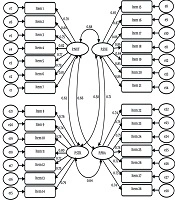

CFA supported the hypothesized four-factor structure of the Thai SRAHP Scale, comprising nutrition, stress management, physical activity, and health responsibility. The model demonstrated good fit to the data (χ²/df = 2.45, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06), satisfying established thresholds for model adequacy (11). All standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.80 to 0.95 and were statistically significant (P < 0.001), indicating strong construct representation. The proportion of variance explained (R²) ranged from 0.64 to 0.90 across domains.

The overall internal consistency was high (Cronbach’s α = 0.93). Subscale reliability coefficients were also strong: nutrition (α = 0.77), stress management (α = 0.86), physical activity (α = 0.91), and health responsibility (α = 0.87). The CR values ranged from 0.84 to 0.93. All AVE values exceeded the recommended minimum of 0.50, supporting convergent validity (See Figure 1). Additionally, criterion validity demonstrated a strong positive correlation between total Thai SRAHP scores and the overall health-promoting behaviors score (r = 0.61, P < 0.001), indicating that participants with higher perceived self-care ability engaged in healthier behaviors.

5. Discussion

This study provides strong evidence supporting the validity and reliability of the Thai version of the SRAHP Scale among older adults with NCDs. CFA confirmed the original four-factor structure—nutrition, stress management, physical activity, and health responsibility—with good model fit indices.

Our findings align with the original English SRAHP developed by Becker et al. (2), which demonstrated strong internal consistency and a clear four-domain structure among U.S. adults with chronic illnesses and physical disabilities, including those with diabetes, arthritis, and mobility impairments. Reported Cronbach’s alpha coefficients in the original validation ranged from 0.82 to 0.94, comparable to the high reliability observed in our Thai sample (2). The strong criterion validity (r = 0.61) indicates that higher SRAHP scores correspond to healthier self-care behaviors, supporting its use for identifying older adults needing targeted interventions. The high factor loadings (0.80 - 0.95) likely reflect strong alignment between the SRAHP domains and Thailand’s emphasis on health responsibility and community-based health promotion. The Nutrition subscale’s lower reliability (α = 0.77) may relate to greater variability in dietary practices. The high test–retest ICC (0.89) further confirms the scale’s stability for repeated use in community and clinical settings. Similar psychometric results were observed in a Turkish validation among women with gestational diabetes, which reported comparable reliability and construct validity (4). The current findings also align with recent studies demonstrating that self-care ability and health awareness significantly predict health outcomes among individuals with chronic conditions (12, 13). These findings demonstrate strong psychometric performance of the Thai SRAHP in this sample and suggest its potential applicability to similar community-dwelling older adult populations; however, broader validation in diverse regions is still needed.

Importantly, this study contributes to the growing body of research validating health behavior assessment tools within Southeast Asian populations. The Thai version of the SRAHP demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.93) and strong factor loadings (0.80 - 0.95), suggesting that older adults were able to clearly understand and respond to the items. Within the Thai context, the health responsibility dimension reflects proactive engagement in routine health check-ups, adherence to medical advice, and active participation in community health initiatives aligned with national primary-care programs. Thailand’s long-standing tradition of community-based health promotion—such as the role of village health volunteers and the integration of mindfulness practices—likely facilitated participants’ comprehension of health responsibility and stress management concepts (7). These culturally embedded factors may help explain the strong psychometric performance observed in the Thai version of the scale.

This study has several strengths, including a rigorous translation process following Beaton et al.’s cross-cultural adaptation framework (10), expert panel evaluation, and face-to-face interviews that minimized literacy-related bias. However, some limitations should be acknowledged. Because this study employed a cross-sectional design, it could not assess the Thai SRAHP’s sensitivity to change or long-term responsiveness. Participants were recruited from a single province, which may limit the generalizability of findings to other ethnic or regional populations. The relatively small sub-sample used for test–retest reliability may also reduce the precision of the ICC estimate. Additionally, cultural norms, such as modesty, respect for authority, and strong trust in healthcare providers, may elevate responses in the health responsibility domain, while community health programs and mindfulness practices may influence perceptions of stress management. Subgroup analyses by literacy level, illness severity, or geographic background were not conducted, as the sample size was optimized for CFA. Future studies with larger, stratified samples and longitudinal designs are recommended.

5.1. Conclusion

The Thai version of the SRAHP Scale is a valid and reliable tool for assessing self-efficacy in health-promoting behaviors among older adults with NCDs. Its four-domain structure aligns with international findings and demonstrates strong internal consistency. The scale can assist healthcare providers in identifying individuals needing support in self-care practices. Its use in community and clinical settings may improve chronic disease management in Thailand. Although the scale demonstrated excellent test–retest reliability in our subsample (ICC = 0.89), future studies should confirm these findings in larger and more diverse populations to enhance generalizability.