1. Context

Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs) are complex conditions involving diverse disabilities (1). Sensory and cognitive deficits often impair self-care — eating, toileting, dressing — leading to caregiver reliance and increased parental and educator burden (2-5). A range of behavioral and instructional strategies has been used to teach self-care skills, including cognitive behavioral therapy, peer tutoring, pictorial schedules, applied behavior analysis, and video-based interventions (6-9). Among these, video modeling (VM) is particularly effective, grounded in Bandura’s social cognitive theory, which emphasizes learning through observation, imitation, and reinforcement (10, 11). This theory involves four processes: Attention, retention, motor reproduction, and motivation. The VM can capture attention, allow task repetition to support retention, segment activities to enhance motor performance, and serve as an internal motivator, with imitation followed by external reinforcement strengthening learning (11). Terminology in video-based instruction varies: The VM shows an individual performing the full target behavior; video prompting presents segmented clips for stepwise performance (12); and self-modeling features the learner performing the correct behavior (13). Clarifying these distinctions is essential for interpreting outcomes across NDD populations.

While VM is widely applied in autism spectrum disorder (ASD), its use in other NDDs — such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and intellectual disability (ID) — for self-care instruction remains underexplored (14). Observational learning and reinforcement operate similarly across these conditions: Children with ASD benefit from visual demonstrations (15); those with ADHD from structured cues that maintain attention (16, 17); and individuals with ID from simplified, stepwise demonstrations that support comprehension (18).

The VM is a cost- and time-efficient alternative for direct teaching of self-care activities (19) but implementation varies by approach (self-, point-of-view, peer, adult modeling), device (TV, handhelds, computers), and setting (home, school, healthcare) (20-23). Awareness of these factors seems crucial for clinical or practical implementation.

To our knowledge, no review has specifically examined VM for teaching self-care in children with NDDs. Existing reviews have focused on ASD or broader daily living skills across ages (11, 14, 24, 25), leaving a gap in understanding how VM’s effectiveness varies by model type, delivery format, or learning context for self-care in NDDs. This limits clinicians’ ability to select the most appropriate evidence-based practices. Focusing on self-care is critical because deficits reduce parental expectations, hinder transition planning, and impact children’s health and quality of life — for example, inadequate toothbrushing in ASD (26, 27).

2. Objectives

Given VM’s benefits and challenges, this study systematically reviews its use for teaching self-care in children with prevalent NDDs — ASD, ADHD, and ID — based on DSM-5 (1), global trends (28), and publication volume (29). Key elements analyzed include model type, video perspective, setting, device, target behavior, and integrated techniques supporting fidelity. The review also identifies conditions that optimize effectiveness and maps applications across special education, occupational therapy, and behavior analysis, addressing a literature gap and guiding future research.

3. Methods

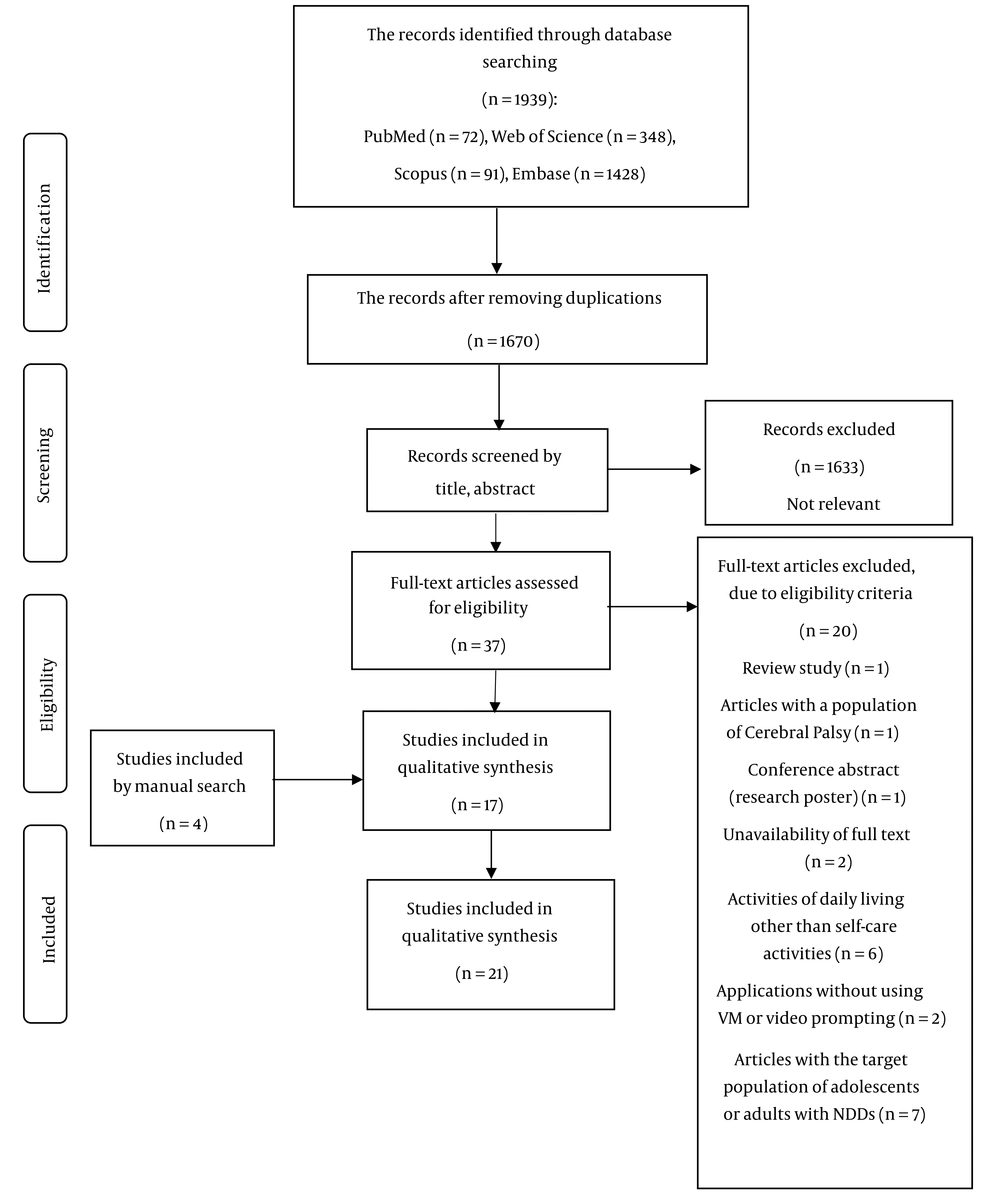

Scoping reviews map existing research to identify gaps without assessing evidence quality (Arksey and O’Malley, 2005) (30). The process includes defining the research question, searching, selecting studies, charting data, and summarizing results. Adherence to the PRISMA-ScR checklist was followed to ensure methodological rigor, and the study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

3.1. Research Questions

This study gathered, charted, and summarized literature on VM for teaching self-care in children with NDDs (ASD, ADHD, and ID). It addressed key questions: Which disorders show the most evidence of effectiveness? Which devices are used for streaming? In what contexts is VM applied? What perspectives and models are used? What additional techniques are integrated? Which self-care activities are targeted? Does effectiveness vary across studies? What generalization strategies are reported?

3.2. Study Identification and Selection

On March 17, 2024, Web of Science, PubMed, Embase, and Scopus were searched using keywords and MeSH terms related to NDDs, self-care, and VM. Boolean operators and truncations were applied; reference lists were also screened (Appendix 1 in Supplementary File). Eligible studies involved VM/video prompting for ASD, ID, or ADHD in participants ≤ 12 years. Reviews, conference papers, non-English or unavailable full texts, adults, and studies without isolated self-care outcomes were excluded. Two authors independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. Pre-review calibration and training ensured consistent application of inclusion/exclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer (Figure 1).

3.3. Eligibility Criteria

Eligible studies used VM or video prompting for children ≤ 12 years with ASD, ID, or ADHD (DSM-5). Excluded were reviews, conference papers, non-English/unavailable texts, older participants, or studies where self-care outcomes were inseparable (Figure 1).

3.4. Data Charting and Reporting

Data extracted included publication year, sample size, diagnosis, region, device, context, model type/perspective, intervention length, study design, self-care targets, and results. Extraction was by the first author and verified by co-authors. Findings are organized into six thematic categories. To enhance rigor in the qualitative synthesis, two authors independently coded themes using NVivo 12, and inter-rater reliability was strong (Cohen’s κ = 0.85).

3.5. Critical Appraisal

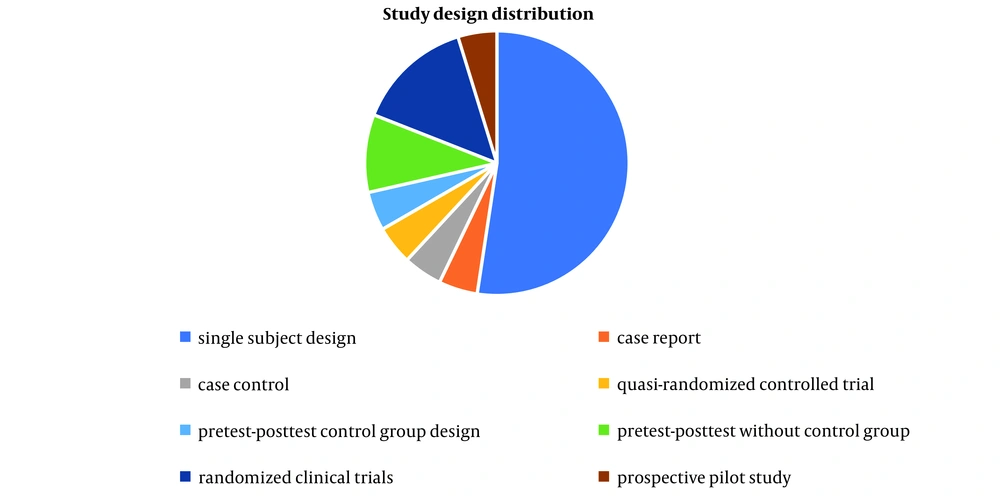

A brief critical appraisal of included studies was conducted to contextualize the findings. Studies varied in design, sample size, age, and diagnosis (ASD, ADHD, and ID). Most employed single-subject or quasi-experimental designs, with only a few controlled or randomized trials. Intervention characteristics, including model type, video perspective, device, duration, and frequency were heterogeneous. Reporting of fidelity, inter-rater reliability, and participant demographics was often incomplete.

4. Results

Results are organized into six categories: (1) Study characteristics (e.g., country, design); (2) participant characteristics (e.g., diagnosis, gender); (3) VM features (e.g., combined techniques, model type and perspective, device); (4) implementation context; (5) self-care targets and outcomes (e.g., activity distribution, effectiveness, evaluation methods); and (6) generalization. Findings are summarized in Table 1. Additionally, the analytical and statistical summaries of the included results are shown in Table 2.

| Authors (y) | Study Design | Sample Size, Age, Gender | Diagnosis | Video Streaming Device | Context of VM | Model type or Video Perspective | Amount of VM Intervention | Self-care Target → Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biederman et al. (1999) (31) | Within-subject design | N = 8, 6 -10 y, 7 girls and one boy | Down syndrome, and ASD | Videotape (via 20-in monitors) | School | Adult female model; point-of-view VM | 6 d; one session of 20 - 30 min per day | Buttoning, snapping, lacing, bow tying → Skills modeled at slower speeds resulted in better observational learning than at faster speeds. |

| Bainbridge and Smith Myles (1999) (32) | ABAB design | N = 1, 3 y, boy | ASD | Any device displaying the toilet training video "It's Potty Time" | Home | Peer (unfamiliar) cartoon; third person perspective | 14 d; three times a day | Toilet training → Use of the video for priming the child led to improvement in the beginning of the toileting and dry diapers. |

| Charlop-Christy et al. (2000) (19) | Multiple baseline design | N = 5 (1 with self-care target), 7 - 11 y, 4 boys and 1 girl | ASD | Videotape | Clinic’s kitchen and a public bathroom near the clinic | Familiar adult modeling (therapists) for both VM and in vivo modeling; third-person perspective | 4 sessions | Brushing teeth → Learning quicker and improvement in generalization, and needing less time and cost in contrast to in vivo modeling |

| Keen et al. (2007) (21) | Multiple baseline design between and across groups | N = 5, 4 - 6 y, boys | ASD | Television and a video player | Home and educational setting | Animation; third person perspective | 6 - 7 times per day; 35 to 110 d (different for each participant in the intervention or control phase) | Toilet training (in-toilet urinations) → Greater frequency of urinations; Maintaining skill for three participants throughout a 6-week follow-up with generalization to a new setting for two participants |

| Rayner (2010) (33) | Case report | N = 1, a 12-year-old, boy | ASD (severe) | Notebook computer | School | Unfamiliar adult; third person perspective | 9 d; 1 - 2 times per day VM | Brushing teeth → 55% completion of the steps during the intervention and follow-up (doubts about motor prerequisites and lack of reinforcement were suggested as possible reasons). |

| Lee et al. (2014) (34) | A changing-criterion design incorporating baseline with follow-up | N = 1, 4 y, boy | ASD | DVD player | Home | Point-of-view modeling and video self-modeling, in vivo modeling for voiding in the toilet bowl (father) | About 113 d; eight times per day | Clothing, sitting, and washing at the toilet → Improving and generalization of these performance skills but not at defecation and urination. |

| Drysdale et al. (2015) (35) | Single-subject A-B design | N = 2, 4 and 5 y, boy | ASD | iPad | Home, and generalization phase in child care center, and special school | Video self-modeling and point-of-view VM; with an animated elimination clip | About 16 - 45 d (different for each participant and each step of toileting); 1 - 8 times per day | Toileting → VM was a rapid and effective method; the skills were maintained over 4 wk after intervention and generalized to the second toilet setting |

| McLay et al. (2015) (22) | A non-concurrent multiple baselines across participants design | N = 2, 8 and 7 y, boys | ASD | iPad | Home | A combination of video self-modeling and point-of-view modeling; with an animation part for urination and defecation | About 76 - 104 d; 5 - 7 times per day (different for each participant) | Toilet training → VM combined with prompting and reinforcement led to independent and successful toileting. So that the skills were generalized to school and retained 3 - 4 mo behaviors necessary for skill generalized to the school and were maintained over 3 to 4 mo. |

| Meister and Salls (2015) (36) | Single-subject A-B design | N = 8 (2 with self-care target), 7.5 - 13.5 y, 7 boys and 1 girl | ASD | iPad | School | Peer (unfamiliar 10 and 13-y children); point-of-view VM | 49 sessions of 10 - 25 min; 3 - 7 sessions for each goal | Tying shoes, washing hands, and wiping mouth → Improvement in task performance during 6 weeks; an average of 50.5% improvement in the goals of all subjects |

| Popple et al. (2016) (37) | Randomized control trial | N = 18, 5 and 14 y, 10 boys and 8 girls | ASD | Any device received an email link | Home | A 10-y girl; Third person perspective | 3 wk; daily | Brushing teeth → Hygiene improved but was not statistically significant; likely due to the small sample size |

| Richard and Noell (2019) (23) | Single-subject multiple baseline design | N = 3, 5 y, 2 boys and 1 girl | ASD (mild to moderate) | A laptop computer | An autism developmental center | First-person point-of-view | 10 - 15 min sessions; frequency is not clear because of different repetitions of each step of the video for each participant | Tying shoes → Video prompt-modeling with backward chaining was effective in the skill acquisition and generalization |

| Susilowati et al. (2018) (38) | A quasi-experimental study with pretest-posttest control group design | N = 62, 6 - 12 y, 40 boys and 22 girls | ID | Screen | Public special school | Third perspective VM (trainer) and in vivo (teacher for control group) | Four 50-min sessions | Dressing skills → Improvement in eight from thirteen skills: Getting clothes from closet and drawer, putting clothes on upper and lower body, buttoning clothes, using zipper and fastener, and removing clothes from the upper body |

| Utami and Pujaningsih (2021) (39) | Single subject design | N = 1, age and gender are not clearly stated (7th grade of special school) | ID (mild) | The device is not clearly stated | A special school | Point-of-view perspective | 6 wk; one session a week | Hand washing → Video media ‘hand washing 6 steps’ improved the ability of handwashing |

| Chawla et al. (2021) (20) | Prospective pilot study | N = 10, 5 - 12 y, 4 girls and six boys | ASD | Smartphone with internet connectivity | A hospital near to the special school | An adult model; third person perspective | 30 d | Brushing teeth → Improvement in the plaque score; compliance towards brushing teeth; less reluctance for brushing teeth |

| Shalabi et al. (2022) (40) | Parallel randomized clinical trial | N = 50, average ages in two VM groups: 8.6 ± 1.1 years (≤ 10 y) and 12.2 ± 2.0 y (> 10 y), 72% male | ASD (mild to moderate) | Video player | Bathrooms of home, and autistic therapeutic center | Animation (downloaded from YouTube); third-person perspective | Three months; | Oral hygiene → Superiority of VM over picture exchange communication system |

| Prabavathy and Alex (2022) (41) | Single-subject design | N = 3, 7, 10, and 12 y, boys | ASD | Mobile phones | Home | Self-modeling | 4 wk | Toilet training → VM was effective |

| Piraneh et al. (2023) (42) | A quasi‑randomized controlled trial | N = 137, 7 - 15 y, boy | ASD | Any device receiving video files via the WhatsApp social network | Home | A 10-y boy; Third person perspective | 1 mo; daily | Oral hygiene → Improvement was significantly better in the VM (with a poster as visual support in the bathroom) than in the social story group in posttest and follow-up |

| Gandhi et al. (2023) (43) | Case-control pilot study | N = 25, 4 - 17 y, 2 girls and 23 boys | ASD (mild to moderate) | Any device received a YouTube email link | Home | Young unfamiliar girl; Third person perspective | 4 wk; twice daily | Oral hygiene → VM and a tooth brushing social story both improved oral hygiene and did not differ, but children were more receptive to the VM than the social story |

| Gurnani et al. (2023) (44) | Randomized controlled trial | N = 54, 7 - 12 y, gender distribution is not mentioned | Attention deficit with hyperactivity disorder | A mobile-phone application | Not mentioned | Animated video, third-person perspective | 12 wk; 1 - 2 times per day | Brushing teeth → Improvement in the brushing time, brushing frequency, and oral hygiene |

| Dalton and Baist (2024) (10) | A quasi-experimental study with pretest-posttest without a control group | N= 11, 6 - 12 y, 8 boys and 3 girls | 5 ADHD, the rest: With comorbidity of learning disorder and autism | Video-making application on mobile device | Clinic | A school-aged peer, a point-of-view perspective | Five 30 - 45-min sessions per week | A variety of self-care skills, including fastening buttons, snaps, and zippers, hair brushing, hand washing, shoe tying, teeth brushing, and utensil use → VM improved independence in these basic self-care skills |

| Andriyani and Putri (2024) (45) | A quasi-experimental study with pretest-posttest without a control group | N = 50, 3 to >15 y, 43 boys and 7 girls | ASD | Watching the video in an open area (the device is not clearly stated) | A center for growth and development therapy for children with special needs | Animated video, third-person perspective | not mentioned; Watching the video repeatedly (probably as often as the child needs to go to the toilet) | Toileting→ Improvement in toileting and elimination process (the ability of 52 % of the subjects increased) |

Abbreviations: VM, video modeling; ASD, autism spectrum disorder; ID, intellectual disability; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

| Categories | Summary/Statistics |

|---|---|

| Number of studies | 21 |

| Mean sample size per study | 21.8 |

| Mean participant age | 8.4 y (range 3 - 17) |

| Gender distribution | ~83% male, 17% female |

| Mean intervention duration | 37.2 d (~5 wk); frequency: 2.2 sessions per day |

4.1. General Characteristics of the Studies

4.1.1. Countries

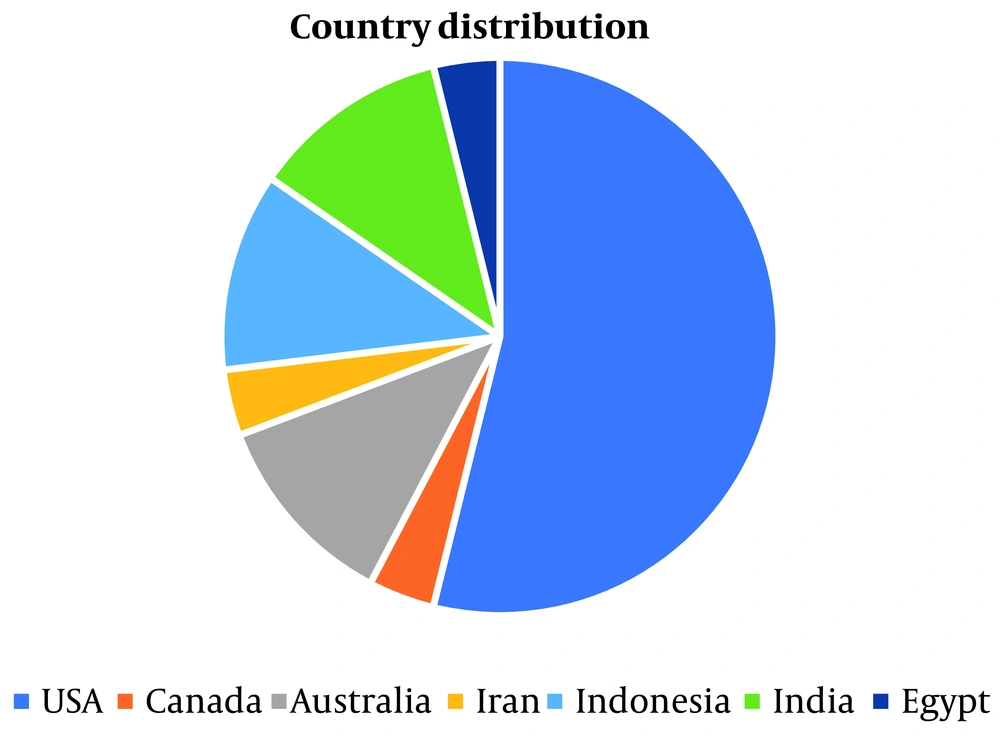

Over half of the studies [14 (66.7%)] were conducted in or after 2015 (10, 20, 22, 23, 36-45). Most [13 (61.9%)] originated from developed countries, mainly the United States [9 (42.9%)] (10, 19, 22, 23, 32, 35-37, 43) and Australia [3 (14.3%)] (21, 33, 34). The remaining studies were from Asian countries [7 (33.3%)] (20, 38, 39, 41, 42, 44, 45) and Egypt [1 (4.8%); Figure 2] (22, 40).

4.1.2. Study Designs

Most studies used a single-subject design [11 (52.4%)] (19, 21-23, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 39, 41). The rest included one case report (33), one case-control study (43), four quasi-experimental studies (10, 38, 42, 45), three randomized clinical trials (37, 40, 44), and one prospective pilot study (Figure 3) (20).

4.1.3. Participant Characteristics

Most studies evaluated VM in children with ASD [16 (76.1%)] (19-23, 32-37, 40-43, 45). Others involved children with ID [2 (9.1%)] (38, 39), Down syndrome with ASD [1 (4.7%)] (31), ADHD [1 (4.7%)] (44), and ADHD with comorbid learning disorder or ASD [1 (4.7%)] (10). Research remains focused on ASD. Eight studies (38.0%) included only male participants (21, 22, 32-35, 41, 42), two did not report gender (32, 44), and eleven (52.3%) had mixed-gender samples (10, 19, 20, 23, 31, 36-38, 40, 43, 45).

4.2. Video Modeling Features

4.2.1. Video Modeling in Combination with Other Techniques

Most studies used VM alone (n = 12), while nine combined it with other techniques: Reinforcement (n = 7), prompting (n = 7), chaining (n = 3), and live modeling (n = 1). Reinforcements included verbal praise, preferred activities (e.g., toys), and edibles. Some relied only on verbal reinforcement (10, 35), while others combined types (21-23, 34, 41), delivered during attempts or after completion. McLay et al. applied a tiered system: Low-level (crackers) for basic steps, moderate (puzzles) for sequences, and high (chocolate with praise) for full task completion (22).

In seven studies combining prompts with VM, all used verbal cues. Most employed multiple prompt types — verbal, physical, visual/pictorial, and gestural (22, 34, 35, 39, 41), while two used verbals only (21, 33). Prompt type sometimes varied by phase; for example, Prabavathy and Alex used physical in week one, verbal in week two, and visual in week three (41). This analysis focused on prompts as performance-enhancing techniques, excluding basic instructions to start the performance or to pay attention to the screen (19, 32, 37).

Of the nine studies combining techniques with VM, three used chaining — two forward (34, 35) and one backward (23). Additionally, Rayner combined VM with in vivo modeling based on prior successful learning outcomes for that case (33).

4.2.2. Video Streaming Devices

Reported video delivery devices included videotape (n = 2) (19, 31), video player (n = 1) (40), DVD player (n = 1) (34), and TV with video player (n = 1) (21). Modern devices were iPads (n = 3) (22, 35, 36), laptops/notebooks (n = 2) (23, 33), and smartphones (n = 4) (10, 20, 41, 44). Three studies used email/WhatsApp (37, 42, 43), and four had unspecified screens (32, 38, 39, 45). Earlier studies used older technology, while recent studies mainly employed smartphones and mobile applications.

4.2.3. Video Perspectives

Most studies used a third-person perspective [12 (57.1%)] (19-21, 32, 33, 37, 38, 40, 42, 43-45). Other perspectives included point-of-view [5 (23.8%)] (10, 23, 31, 36, 39), combined self-modeling and point-of-view [2 (9.5%)] (22, 35), self-modeling alone [1 (4.7%)] (41), and combined self-modeling, point-of-view, and in vivo modeling [1 (4.7%)] (34).

For toileting, three studies used a third-person perspective (21, 32, 45), while others applied point-of-view with video self-modeling and in vivo modeling (19), point-of-view plus animated elimination clips (22, 33), or self-modeling alone (41).

For oral hygiene (toothbrushing), all studies used a third-person perspective (19, 20, 33, 37, 40, 42-44). For fine motor dressing tasks (e.g., zipping, buttoning, tying), point-of-view modeling was predominant (10, 23, 31, 36), though one study used third-person for general dressing (38). Point-of-view was also preferred for handwashing, hair brushing, and utensil use (10, 36, 39), indicating third-person suits gross motor tasks, while point-of-view is more effective for fine motor tasks.

4.2.4. Types of Models

The VM interventions used peers, adults (familiar/unfamiliar), animations, and self-models. Adult models appeared in five studies (19, 20, 31, 33, 38) and peer models in five (10, 36, 37, 42, 43). Among third-person perspective studies, four used adults (19, 20, 33, 38), three peers (37, 42, 43), four animations (21, 40, 44, 45), and one peer cartoon (32).

4.2.5. Video Streaming Speed

Only one study compared video speeds (31); lower speed yielded higher, but not statistically significant, performance scores.

4.2.6. Cross-Relationship Between Model Type, Video Perspective, and Self-care Targets

Analysis of the included studies revealed clear links between self-care skill type and video perspective/model. Third-person perspectives were used exclusively for gross motor or routine tasks, such as toothbrushing and oral hygiene, in all 8 relevant studies (19, 20, 33, 37, 40, 42-44). Point-of-view modeling was used for fine motor tasks — dressing, handwashing, shoe tying — in all 5 relevant studies (10, 23, 31, 36, 39). Self-modeling or combined approaches were mainly applied to complex sequences like toilet training (50% of toileting studies) (10, 22, 34-36, 41). These findings indicate that task type shapes the choice of video perspective and model: Gross motor routines align with third-person adult, peer, or animated models, while fine motor and sequential skills benefit from point-of-view or self-modeling videos. This highlights the importance of matching VM formats to targeted self-care skills to optimize learning outcomes.

4.3. Context

Most VM interventions were conducted at home [7 (33.3%)] (22, 32, 34, 37, 41-43), followed by schools [5 (23.8%)] (31, 33, 36, 38, 39), and three used both home and another setting (14.2%) (21, 35, 40). Other contexts included clinics, autism centers, hospitals, therapy centers, and unspecified settings (10, 19, 20, 23, 44, 45). Home was common for toilet training (22, 32, 34, 35, 41), oral hygiene (40, 42, 43), and toothbrushing (37); schools for dressing (31, 38), toothbrushing (33), shoe tying, handwashing, and mouth wiping (36, 39); clinical settings for toothbrushing (19, 20), oral hygiene (40), and dressing/grooming (10, 23).

4.4. Targeted Self-care Outcomes

4.4.1. Activity Distribution

Targeted activities included toothbrushing [8 (38.1%)] (19, 20, 33, 37, 40, 42,-44), toilet training [7 (33.3%)] (21, 22, 32, 34, 35, 41, 45), handwashing [1 (4.8%)] (39), dressing [2 (9.5%)] (31, 38), shoe tying [1 (4.8%)] (23), and multiple activities [2 (9.5%)] (10, 36).

4.4.2. Effectiveness

95.2% (20 of 21) of the studies reported positive VM effects. Only one study showed limited success in toothbrushing, likely due to small sample size (37).

4.4.3. Evaluation Methods

Fourteen methods assessed self-care, including mean number/percentage correct performances (32), frequency of correct performance (21, 37, 40, 43), number of sessions with correct performance (19, 36), number of independent steps (22, 23, 33, 34, 41), number of prompts used (35), percentage of time of correct performance (22), interest level in performance (37), efficiency/time required for performance (40), caregiver perceptions (43), and score analyses (10, 23, 31, 37, 38, 42-45).

For toileting, evaluations included mean daily toilet initiations, dry diapers, or percentage of dry diapers (32); frequency of urination in toilet and consistent in-toilet patterns (21); steps completed independently or without prompts (22, 34, 41); number of prompts (35); percentage of time urinating in toilet (22); and score analyses via questionnaires/checklists (45).

Toothbrushing/oral hygiene evaluations included 100% correct steps across two sessions (19), number of correct steps (33), brushing frequency (32, 38), parental oral health scores, plaque detection (mean ± SD), child interest (37), Mean Plaque Index difference (44), and brushing efficiency/time (40), and caregiver perceptions (44).

Dressing/Other Skills included mean score differences post-observation (31), VM sessions to competency (42), number of VM sessions for competency in shoe tying (36), score differences on hand washing ability test (23) or on Waisman Activities of Daily Living Scale (10), and skills like fastening buttons/snaps/zippers, hair brushing, handwashing, shoe tying, toothbrushing, and utensil use (38).

4.5. Generalization

Six studies assessed generalization, mostly across settings (n = 4). Settings included novel environments (21), different toilets (22, 34, 35), and across persons, settings, and stimuli (19). For fine motor skills like shoe tying, generalization was assessed sequentially across multiple trials (23). Overall, VM demonstrated moderate to strong generalization potential, particularly when interventions included reinforcement or chaining.

5. Discussion

This review examined VM interventions for self-care in children with NDDs. The VM was generally effective, though Popple et al. found no improvement in toothbrushing for ASD, likely due to a small sample (n = 18) (37). Limited randomized trials [three: (37, 40, 44)] and study heterogeneity restrict high-level evidence. The VM is less adopted than cognitive therapy or applied behavior analysis, likely due to technology access and therapist expertise. Most studies are from the United States and Australia, while research from developing countries (e.g., Iran, India, Indonesia, Egypt) enhances generalizability.

The VM efficacy can be explained through social learning theory and applied behavior analysis. Social learning theory posits that children learn by observing models, with attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation as key processes (11). The VM offers repeated visual demonstrations that enhance attention and retention, especially for children with ASD who prefer visual learning (12, 13, 46). Charlop-Christy noted VM often outperforms in vivo modeling for teaching daily skills in ASD, likely due to intrinsic motivation, novelty, and the ability to focus on specific steps, addressing stimulus over-selectivity (19). Applied behavior analysis principles, including prompting and reinforcement, further explain the faster acquisition and generalization in VM, with video practice resembling discrete trials where instruction, response, and reinforcement are repeated (47).

Cognitive and perceptual features of NDDs affect responses to VM: Children with ASD benefit from structured, repetitive visuals, those with ADHD need brief, stimulating videos to maintain focus, and children with ID or Down syndrome may require simplified steps and extra cues (15-). However, most studies rarely linked these population characteristics to VM design. Research has focused mainly on ASD (24, 48, 49), likely due to responsiveness to visual, repetitive learning (15, 46). In one study found visual cues help both typically developing children and those with NDDs, not just ASD, but studies on ADHD, Down syndrome, and ID remain limited (23, 24, 40). The VM improvements were mostly seen in ASD levels 1 - 2, with level 3 showing only 55% improvement in toothbrushing, suggesting reduced effectiveness for severe symptoms (33).

The VM can be delivered via mobile phones, tablets, TVs, and computers (21, 33, 36, 44), with a trend toward smartphones. While larger screens might seem better for capturing attention, studies show smaller devices like iPads and phones can be effective for children with NDDs, including ASD (15, 20, 50, 51). Campbell et al. reported handheld devices work well (50); Plavnick noted engagement benefits (15); Chawla et al. used smartphones for toothbrushing (20); and Cihak et al. highlighted their usefulness where TVs or computers are unavailable (51).

Models used include self, peer, familiar/unfamiliar adult, and point-of-view, all showing effectiveness. Meta-analyses report no differences between VM and self-modeling (52) or between first- and third-person perspectives (53). Our review found no superiority among peer, adult, or other models (19, 21, 34, 36). The VM also supports skills such as pretend play, shopping, handwashing, and dressing (49, 54), and demonstrates faster learning and better generalization than in vivo modeling (19). Lee (2014) noted that, unlike VM, in vivo modeling did not generalize elimination in toileting (34).

Findings indicate that real-world training enhances self-care learning. Most studies used home and school settings (21, 34, 38). Implementers — teachers or parents — provide critical social context. Clinic/school staff were usually qualified; parental qualifications rarely reported. Higher parental education improved awareness of non-practice consequences, enhancing VM implementation and outcomes (45).

Studies show VM is often combined with other behavioral techniques when self-care tasks are too complex for visual learning alone (23, 35, 39, 41). Choice of complementary strategies depends on the child’s abilities and support needs. Following the principle of just-right challenge, activities should allow successful completion with minimal effort (55), and different techniques can be used at different stages of learning (22, 41). Most included studies applied strategies such as prompting, chaining, reinforcement, and verbal or gestural cues to align with this principle (21, 22, 33-35, 39, 41).

About 95% of studies reported skill improvements, with one exception likely due to a small sample size (37). The VM is cost-efficient, time-saving, and requires few sessions (19, 33). Toileting and toothbrushing were most frequently targeted, likely because their multi-step nature and children’s auditory processing difficulties make visual instruction more effective than verbal guidance for these tasks (56).

The VM was generally effective, but maintenance and generalization were inconsistently addressed. Ayres and Langone (53) reported variable generalization for grocery shopping and food preparation, likely due to task complexity and stimuli variability. No gender differences were found; Shalabi et al. explicitly confirmed this (40).

5.1. Conclusions

The VM effectively supports children with NDDs, especially ASD, in cost- and time-efficient ways. Clinicians and parents can use VM to teach self-care, enhancing independence and skill acquisition.

5.2. Implications

The VM should be applied across all NDDs, with consideration for ASD severity and appropriate behavioral techniques. Device selection allows customization, and familiar settings optimize outcomes. Slower playback and varied contexts support children with slower processing. Outcome metrics include task duration, number of prompts, and steps completed, while video perspective should align with the type of activity.

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations

Despite promising outcomes, several limitations should be noted. Variability in terminology, small sample sizes, and reliance on single-subject designs increase susceptibility to bias. Maintenance and generalization were inconsistently assessed, limiting understanding of long-term effects. Future research should prioritize standardized randomized controlled trials with larger, diverse samples, long-term follow-ups, and cross-cultural adaptation. Expanding studies to underrepresented NDDs, comparing intellectual versus motor impairments, and examining age-related differences will strengthen the evidence base. Integrating theoretical frameworks can guide intervention design by linking cognitive-perceptual profiles to model selection and video format.