1. Background

Body dysmorphic disorder is a psychological condition that causes people to be overly focused on their perceived facial or bodily imperfections (1). Although these imperfections are usually imperceptible or hardly evident to others, the individual experiencing them considers them a significant source of discomfort and distress (1).

While individuals affected by the condition may be unhappy with various aspects of their appearance, they usually concentrate on their facial characteristics like nose, eyes, skin, and hair (2). The prevalence of this illness is 1.9 percent in the general population and 5.8 to 7.4 in the clinical adult population (3). In terms of gender differences, higher rates of body dysmorphic disorder have been observed in women compared to men (1). This disorder is associated with impairment across various psychological domains, one of the most important of which is the perception of one's appearance or body image. Individuals with this disorder experience a very negative and inappropriate perception of their bodies, which is accompanied by an immense amount of shame. Body image is an intricate psychological concept which includes individuals’ evaluation of their bodily appearance along with the feelings, behaviors, and thoughts that are linked with their physical self (4). Individuals with more distorted body image and greater dissatisfaction with their looks are at a higher risk of developing body dysmorphic disorder (5). This poor body image is also often accompanied by emotional problems and dysfunction in regulating emotions, which primarily manifests as depression, stress, and anxiety (5, 6). These individuals struggle to use appropriate emotion regulation strategies to manage negative emotions, which may lead them to use maladaptive strategies such as frequent mirror checking, avoidance, or obsessive rituals (7).

On the other hand, some research suggests that individuals with body dysmorphic disorder believe that it is possible to have such ideal bodies, which is extremely difficult to attain, and as a result, they start to think negatively about their bodies (8). Consequently, positive psychotherapy (PPT) might represent a noteworthy support for these patients. This kind of therapy is a major shift from focusing on symptoms to emphasizing patients’ coping resources. In fact, these therapists believe that other forms of psychotherapy, which primarily focus on problems, might help reduce those issues but may overlook the positive and adaptive strengths of the person (9). According to PPT, mental health issues should be addressed by utilizing positive personality traits, positive emotional experiences, and a sense of meaning in life rather than focusing on reducing unpleasant symptoms (10). Focusing on gratitude and valuing achievements is among the various techniques employed in PPT to foster increased positive thoughts, feelings, and actions (9). Research findings indicate the effectiveness of this approach in reducing depression (11), increasing life satisfaction (12), and boosting subjective well-being (13).

To address psychological issues in patients with body dysmorphic disorder, it is crucial to be open, nonjudgmental, and compassionate toward their real appearance (14, 15). In other words, having a non-judgmental and compassionate attitude is associated with improved distress tolerance and reduced fear of physical deformity (15, 16). On the other hand, one treatment in which self-compassion is a key element is acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). It is based on principles that directly address the core symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder such as inflexible thinking, avoidance, and impaired life quality (17). Specifically, ACT aims to support individuals in building psychological strength, learning to cope with difficult emotions and challenges, and focusing on achieving meaningful life goals (18).

There is research on the effectiveness of ACT on psychological problems such as anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, and body preoccupation; however, such studies are limited (15, 16). The case-based or follow-up-deficient nature of these studies, as well as their failure to assess treatment adherence during follow-up, were among their main flaws. In fact, few studies have examined the extent to which this treatment works for body dysmorphic disorder in terms of emotion regulation and body image. Furthermore, although positive psychology has been found to be effective, its effect on patients with body dysmorphic disorder has not been examined in relation to emotional difficulties and body image. Failure to address this problem will exacerbate its complexity and severity, potentially leading to suicide. Many of these patients also visit dermatologists, cosmetic surgeons, orthodontists, urologists, and gynecologists, which raises healthcare expenses (19). As a result, having psychologists diagnose and treat these patients can dramatically lower the costs. On the other hand, because ACT and PPT are both short-term and cost-effective treatments, psychotherapists can use them to improve the emotional problems and body image perception in these patients.

2. Objectives

To the best of our knowledge, no comprehensive study has been carried out to compare the effects of positive psychology and ACT on emotion regulation and body image in women with body dysmorphic disorder.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design

The current study utilized a randomized controlled experimental design with three groups. The study had three groups: The PPT (20 people), ACT (20 people), and control (20 people). Following registration with the Iranian Clinical Trial Registration System (IRCT20250315065087N1) and ethical approval from the Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon Branch Research Ethics Committee, the study commenced (IR.IAU.TON.REC.1404.005). All women with body dysmorphic disorder in Tehran during 2024 - 2025 who had been referred to hospitals and psychotherapy clinics were included in the study population.

3.2. Participants

Sampling in this study was done using the convenience sampling method. In cyberspace and on social media platforms such as Telegram and Instagram, an announcement was made about the current study, explaining that it aimed to investigate the effectiveness of two therapeutic approaches, ACT and PPT, for individuals concerned about their appearance. Interested individuals were invited to contact a phone number provided in the announcement to participate in the study. Afterward, patients were contacted by phone, and a face-to-face meeting and diagnostic interview were conducted. Additionally, announcements and information about the study were provided in the Rasta and Insight Psychotherapy Clinics, Iran Psychiatry Hospital, Arasteh Beauty Clinic, and Dr. Najmeh Ahmadi Beauty Clinic. After the subjects were referred, a diagnostic interview was conducted by a doctoral student. The diagnosis was based on the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (SCID-5-CV), which was carried out by a PhD student in psychology under the supervision of a member of the board committee. Those who met the diagnostic criteria were included in the study.

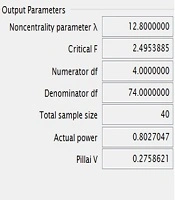

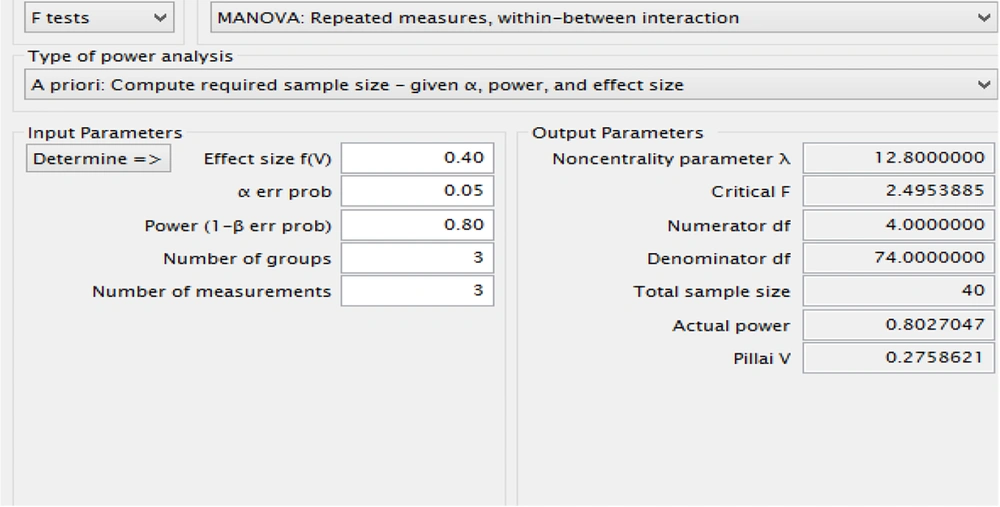

Before the intervention began, the subjects were given the necessary explanations about the purpose and title of the study. They were also given the necessary explanations about the intervention process, duration of the intervention, benefits of participating in the study, and maintaining confidentiality. Using G*Power and based on a previous study (20), the required sample size was calculated to be 40 participants, with an effect size of f = 0.40, a statistical power of 0.80, and a significance level of 0.05 (Figure 1).

To account for potential participant attrition, the sample size was increased to 60, divided equally into three groups: A control group (n = 20), an ACT group (n = 20), and a PPT group (n = 20).

Eight of the 68 individuals who expressed interest in taking part in the study were excluded because they did not fit the inclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria for the study included: Between the ages of 18 and 45, able to read and write, have a diagnosis of body dysmorphic disorder based on a diagnostic interview, not having serious suicidal thoughts, and not having a mental illness that interferes with reality, such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. The following were among the exclusion criteria: Concurrent psychotherapy; severe suicidal thoughts; chronic physical illnesses that affect weight and appearance; use of medical or psychiatric medications affecting weight and appearance; substance abuse; and severe disorders like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder that interfere with reality testing.

One participant in the post-test phase and one in the ACT group were unable to finish the follow-up phase. In the group that received PPT, two individuals did not finish the follow-up phase because they missed psychotherapy sessions, and one individual did not finish the post-test. Three participants in the control group, however, did not finish the follow-up period and post-test.

Interested individuals were invited to contact the research team through a designated phone number or email address to express their willingness to participate. Following an initial diagnostic interview conducted by a doctoral student in psychology, participants who met the criteria for body dysmorphic disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) were included in the study. Eligible participants were then randomly assigned to one of three groups: The ACT, PPT, or control. Participants were assessed at three times, including a pre-test, a post-test, and a 3-month follow-up. In order to comply with ethical standards, participants completed an informed consent form before the intervention. They were also free to withdraw from the study at any time. Therapists were trained on the approaches used. The intervention process was also conducted under the supervision of an expert specializing in ACT and PPT. The participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group according to a computer-generated random allocation sequence.

3.3. Intervention

Participants in the ACT group received eight weekly sessions following the treatment protocol developed by Eifert and Forsyth (Table 1) (21). Participants in the PPT group received intervention sessions based on Magyar’s (22) approach, with the session content summarized in Table 2.

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | Establishing a therapeutic relationship and introducing the research topic |

| Session 2 | Discussing personal experiences, introducing creative hopelessness, and evaluating efficacy as a measurement criterion |

| Session 3 | Identifying control as a source of struggle, introducing willingness as an alternative response, and engaging in values-guided actions |

| Session 4 | Applying cognitive diffusion techniques, addressing problematic language patterns, and reducing attachment of self to thoughts and emotions |

| Session 5 | Observing self as context, reducing attachment to self-as-concept, and fostering self-as-observer perspective |

| Session 6 | Practicing mindfulness and present-moment awareness, modeling stepping out of the mind, and training in seeing experiences as ongoing processes |

| Session 7 | Introducing the concept of values, pointing out the disadvantages of focusing on results, discovering the practical values of life, describing differences between values, goals, and common mistakes, identifying the internal and external barriers |

| Session 8 | Determining patterns of actions aligned with values, identifying value-driven behavior plans and creating a commitment to them |

| Sessions | Content |

|---|---|

| Session 1 | Introduction and building therapeutic rapport, establishing a non-judgmental and non-blaming environment, explaining the principles and roles of PPT, and assigning the first homework task |

| Session 2 | Reviewing the previous session’s homework, and exercises for self-expression and emphasizing personal strengths and positive qualities |

| Session 3 | Reviewing previous exercises, planning and practicing the client’s capabilities, exploring commitment and the relationship between current strengths and experienced emotions, and introducing techniques to enhance positive emotions, hope, optimism, and focus |

| Session 4 | Reviewing previous homework, exploring the role of past memories (positive and negative) in emotional experiences and symptom development, discussing how to reinterpret past experiences, and assigning relevant exercises |

| Session 5 | Reviewing previous homework, introducing forgiveness exercises to reduce anger and resentment, practicing letter-writing for forgiveness, and applying “sweet-making” techniques to enhance personal happiness |

| Session 6 | Reviewing previous homework, reflecting on positive and negative memories, practicing strategies to reduce body image concerns, and exercises aimed at cultivating gratitude, self-esteem, and self-confidence |

| Session 7 | Reviewing previous homework, receiving client feedback on the experience of positive emotions, and reinforcing progress and motivation |

| Session 8 | Consolidating previous exercises, discussing overall life strategies and applying positive psychotherapy principles in daily life, introducing new exercises to promote ongoing personal growth, and reviewing uncompleted techniques and achievements |

Abbreviation: PPT, positive psychotherapy.

3.4. Instruments

3.4.1. Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition

The SCID-5-CV is a semi-structured interview designed to diagnose psychiatric disorders according to the DSM-5, administered by clinicians or trained mental health staff (23). The reliability and validity of this tool were studied. Threshold agreement for various disorders was set at 0.70 and above, and the sensitivity and specificity of the interview were reported to be 0.70. The Cohen’s kappa for various disorders was calculated at 0.73 - 0.94 (24). The psychometric properties of the Persian version were examined, with results showing high Cohen’s kappa (above 0.80) for all disorders except for anxiety disorders (0.75). Moreover, the sensitivity of this tool for all diagnoses was reported to be above 0.80. The threshold agreement for various disorders was reported at 0.70 (25). In this study, Cohen’s kappa was calculated as 0.91.

3.4.2. Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale

This scale was developed in 2004 and is based on the acceptance-based and mindfulness-based conceptualization of emotion regulation. This is a comprehensive instrument for assessing emotion regulation difficulties (26). The 36 items on this self-report scale measure both the general and specific features of difficulties in emotion regulation. Higher scores on this scale indicate higher levels of difficulty in emotion regulation. The scale's aspects include: Inability to control impulses, difficulties executing goal-directed behaviors, lack of emotional awareness, restricted access to emotion regulation strategies, and emotional clarity issues. The original Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS) demonstrated excellent psychometric properties, with an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.93 and a test-retest reliability of 0.88. Its construct validity and predictive validity were also reported to be satisfactory (26). The scale has been translated and standardized in Iran, where the Persian version showed acceptable reliability and validity: Subscale Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.66 to 0.88, test-retest reliability ranged from 0.91 to 0.97, and both construct and criterion validity were found to be satisfactory (27). The reliability of this questionnaire was calculated using Cronbach's alpha, which was 0.83.

3.4.3. Fisher Body Image Test

Fisher developed the 46-item Fisher Body Image Test (BIT), a questionnaire that measures how individuals feel about their bodies. A five-point Likert scale is used to score each item, with 1 indicating "very dissatisfied" and 5 indicating "very satisfied". The more negative the respondent's view of their body image, the higher their overall scores will be. The original version demonstrated acceptable psychometric properties, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81 and a convergent validity coefficient of 0.47 (28). The test has also been standardized in Iran by Yazdanjo, reporting a test-retest reliability of 0.82 and convergent validity of 0.42, indicating satisfactory reliability and validity in the Persian version (29). The reliability of this questionnaire was calculated using Cronbach's alpha, which was 0.74.

3.4.4. Data Analysis

The data in this study were analyzed using SPSS-26 software, and the descriptive part included frequencies, means, standard deviations, and percentages. For the inferential section, repeated measures analysis of variance was reported. Additionally, the assumptions of the tests, including the M-Box test, Shapiro-Wilk test, Mauchly’s sphericity test, and Levene’s test, were examined and reported. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test showed that distribution in difficulty in emotion regulation (Statistic = 0.983, P = 0.67) and body image (Statistic = 0.991, P = 0.72) was normal. The M-Box test for body image (M-Box = 17.73, P = 0.18) and difficulty in emotion regulation (M-Box = 9.91, P = 0.70) were not significant. Therefore, the assumption of homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices was properly met. The results of Levene’s test for body image (F = 2.13, P = 0.12) and difficulty in emotion regulation (F = 0.03, P = 0.96) were not significant, indicating homogeneity of variance for the variables. Mauchly's sphericity test was used to examine the sphericity assumption, and the results indicated that the sphericity assumption was met for difficulty in emotion regulation (Mauchly's W = 0.991, P = 0.783) and body image (Mauchly's W = 0.891, P = 0.491).

4. Results

The participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in Table 3. Analysis of the data indicated no significant differences among the groups with respect to these characteristics.

| Variables | Values | P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.48 | |

| ACT | 26.05 ± 2.35 | |

| PPT | 28.26 ± 3.33 | |

| Control group | 25.41 ± 2.05 | |

| Education status | 0.39 | |

| Diploma degree or less | ||

| ACT | 5 (25.00) | |

| PPT | 3 (15.00) | |

| Control group | 5 (25.00) | |

| Bachelor | ||

| ACT | 8 (40.00) | |

| PPT | 10 (50.00) | |

| Control group | 6 (30.00) | |

| MSc | ||

| ACT | 4 (20.00) | |

| PPT | 5 (20.00) | |

| Control group | 7 (20.00) | |

| Ph.D. | ||

| ACT | 3 (15.00) | |

| PPT | 2 (10.00) | |

| Control group | 2 (10.00) | |

| Marital status | 0.42 | |

| Single | ||

| ACT | 6 (30.00) | |

| PPT | 5 (25.00) | |

| Control group | 8 (40.00) | |

| Married | ||

| ACT | 14 (70.00) | |

| PPT | 15 (75.00) | |

| Control group | 12 (60.00) | |

| Employment status | 0.53 | |

| Employed | ||

| ACT | 13 (65.00) | |

| PPT | 15 (75.00) | |

| Control group | 12 (60.00) | |

| Housekeeper | ||

| ACT | 7 (35.00) | |

| PPT | 5 (25.00) | |

| Control group | 8 (40.00) |

Abbreviations: ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; PPT, positive psychotherapy.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

Table 4 provides additional information on demographic data for the participants. The mean and standard deviation of the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up scores of the study variables for the intervention and control groups are displayed as descriptive indicators in Table 4.

| Variables | Pre-test | Post-test | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Image | |||

| ACT | 66.05 ± 10.20 | 81.38 ± 9.79 | 79.11 ± 5.98 |

| PPT | 65.11 ± 5.06 | 74.00 ± 6.80 | 73.05 ± 9.05 |

| Control | 63.96 ± 8.81 | 66.11 ± 11.03 | 65.64 ± 6.47 |

| P-Value | 0.786 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| DERS | |||

| ACT | 94.44 ± 10.14 | 78.50 ± 8.29 | 77.05 ± 10.26 |

| PPT | 92.94 ± 10.51 | 84.29 ± 8.34 | 88.17 ± 10.88 |

| Control | 94.17 ± 9.56 | 98.52 ± 11.48 | 94.52 ± 7.45 |

| P-Value | 0.897 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; DERS, Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale; PPT, positive psychotherapy.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

Both PPT and ACT led to improvements at the post-test; however, the magnitude of improvement was greater in the ACT group (P < 0.01).

Before analyzing the hypotheses, the data were examined to ensure that the research data met the underlying assumptions of the repeated measures analysis of variance. Table 5 presents the results of the repeated-measures mixed analysis of variance, comparing post-test scores with pre-test scores across the experimental and control groups for each variable.

| Variables | F | MS | df | P-Value | Eta Squared |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body image | |||||

| Interaction effect | 3.85 | 288.014 | 2 | 0.028 | 0.13 |

| Within effect | 17.81 | 1311.643 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.26 |

| Between effect | 16.81 | 1376.782 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.40 |

| DERS | |||||

| Interaction effect | 7.300 | 733.926 | 2 | 0.002 | 0.23 |

| Within effect | 8.141 | 853.825 | 2 | 0.006 | 0.14 |

| Between effect | 27.099 | 2033.916 | 2 | 0.001 | 0.52 |

Abbreviation: DERS, Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale.

As shown in Table 5, ACT and PPT led to significant changes in emotion regulation and body image. Table 6 presents the results of the Bonferroni post hoc test for comparison between groups in the research variables.

| Variables | Standard Error | Mean Differences | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Image | |||

| ACT | |||

| PPT | 1.767 | 4.793 | 0.028 |

| Control | 1.767 | 10.244 | 0.001 |

| PPT | |||

| Control | 1.792 | 5.451 | 0.012 |

| DERS | |||

| ACT | |||

| PPT | 1.692 | -5.137 | 0.011 |

| Control | 1.692 | -12.412 | 0.001 |

| PPT | |||

| Control | 1.716 | -7.276 | 0.001 |

Abbreviations: ACT, acceptance and commitment therapy; PPT, positive psychotherapy; DERS, Difficulty in Emotion Regulation Scale.

The results indicate that ACT was more effective than both PPT and the control group. In addition, PPT was more effective than the control group.

5. Discussion

The results of this study showed that ACT, compared with the control group and PPT, led to improved body image in women with body dysmorphic disorder, a finding that is also consistent with previous research (15, 17, 30-33). In addition, PPT also led to improved body image, and the results of both experimental groups were consistent with research that has confirmed the effectiveness of psychological interventions in improving body image (34, 35). To explain this finding, it can be stated that patients with body dysmorphic disorder have fundamentally negative beliefs about their appearance and social approval (17, 33). The ACT, on the other hand, encourages patients to accept and not engage with their thoughts rather than trying to eliminate them. This is associated with improved body image and decreased self-criticism regarding their appearance. This therapy encourages patients to separate their ideas and feelings from their identity and who they are, thus mitigating the harmful impact of negative self-perceptions regarding appearance (32, 36, 37). In fact, this therapy assists patients in letting go of the cognitive control strategies they used to engage in, not defusing with their problematic thoughts, and managing their unpleasant emotions (38, 39).

This disengagement and detachment from self-critical thoughts is associated with a decrease in the person's sensitivity to negative attitudes regarding their appearance and acceptance of their current self (40, 41). The use of defusion makes people feel less resentful towards their physical features. This method reduces unpleasant emotions, as well as negative thoughts and actions related to body image (40, 41). Shame about appearance and internal and external avoidance of confronting appearance are significant issues in body dysmorphic disorder. Individuals who participate in ACT are urged to confront their shame, which may at first make them think more negatively about their appearance but eventually improves those thoughts (16). Another important therapeutic strategy for improving body image is the reappraisal process, which is particularly addressed in ACT. This reappraisal reduces patients' excessive attention to and obsessions with their body image (40, 41). Similar studies have also indicated that shame declines slowly at the start and middle of treatment, but improves more quickly after treatment and follow-up, because the individual learns to confront this shame, which initially raises shame but eventually leads to improvement. In fact, the patients learn to confront and communicate with the feeling of shame that they were avoiding. In an acceptance and commitment-based therapeutic approach, awareness and openness to unpleasant thoughts and feelings, including shame, is a key way to lessen the harmful effects of these internal experiences (16, 18).

Additionally, PPT improves individuals’ body image by emphasizing their positive and adaptive traits and strengthening their positive attitude towards intrapsychic and interpersonal issues. In fact, improving individualism, self-actualization, and positive subjective well-being can reduce negative symptoms, such as a poor self-image, particularly regarding one's body (10, 42). Indeed, according to the PPT approach, strengthening positive thoughts can help improve symptoms of psychological problems. When symptoms such as concerns about appearance or body image increase, there is a greater need and necessity for having pleasure, meaning, and a purposeful life. This can be strengthened by increasing positive thoughts and feelings or by confronting negative thoughts (43, 44). Additionally, in this therapy, participants are encouraged to focus on the positive characteristics of their looks, which contributes to the enhancement and reinforcement of individuals' positive appraisal of their own bodies (43, 45). On the other hand, enhancing a positive attitude toward one's own body and giving oneself positive feedback in front of the mirror are crucial for enhancing one's body image. This intervention took into account another crucial element in enhancing body image. However, it can be argued that one of the most significant issues for patients with body dysmorphic disorder is distorted body perception, shame about their appearance, and avoidance of confronting negative thoughts about body image (16). This is especially evident when considering the greater effectiveness of ACT compared to PPT. However, in the ACT approach, in addition to self-compassion, accepting negative thoughts and perceptions of one's body gradually reduces the effects of negative thoughts while also improving a positive attitude toward the body.

This study also found that patients with body dysmorphic disorder who received PPT and ACT showed improvements in emotion regulation. However, the rate of improvement in ACT was higher than that of PPT, which is in line with other studies (20, 46, 47). In ACT, individuals primarily learn to put their negative experiences in a compassionate framework, which enables them to have a kind of appreciative and empathetic attitude toward themselves even in stressful situations and, consequently, experience fewer emotional problems (46, 48). This may help to explain these findings. One of the most important components of emotion regulation is acceptance and non-avoidance of unpleasant emotions, which is one of the most important key concepts and therapeutic goals of ACT (20, 21). Patients learn to observe emotions independently of whether they are pleasant or unpleasant, and to accept them without becoming involved, using mindfulness techniques. This acceptance leads to a reduction in the negative impact of negative emotions and an increase in self-compassion. This acceptance also enhances distress tolerance, which improves the individual's emotion regulation skills (16).

5.1. Conclusions

Overall, the findings of this study suggest that ACT is an appropriate treatment for patients with body dysmorphic disorder, and that mental health psychotherapists can use this therapy to improve body image and emotion regulation problems in these patients. Since many of these patients are encountered in non-psychiatric settings, psychologists can help prevent the adverse effects of unnecessary medical interventions by accurately diagnosing and identifying these individuals, thereby enabling the provision of appropriate treatment. Furthermore, because issues related to body image are becoming more common in society, the severity of the disorder can be alleviated by diagnosing and recognizing these people and intervening in a timely manner using an effective ACT.

5.2. Limitations

Despite achieving our goals, the present study also had some limitations that should be considered when generalizing the findings. First, the present sample included women, which limits the generalization of the findings to men. Despite the three-month follow-up period, it seems that longer follow-up periods are needed to examine the durability of treatment. Furthermore, questionnaires were employed to measure the outcome variables in this study, which, due to the nature of the instrument and the psychological characteristics of the individual at the time of completion, could result in bias. Consequently, it is recommended that future research on the efficacy of these therapies be carried out with a longer follow-up time and in a gender-balanced sample including both men and women. Additionally, more precise and objective instruments are better suited to assess the efficacy of the therapy process.