1. Background

Nephrolithiasis, or kidney stone disease, is a pervasive global health concern with a history spanning millennia; however, it continues to impose a significant burden of morbidity and economic costs on healthcare systems worldwide (1). The pathogenesis often involves urinary supersaturation, leading to the crystallization of salts, such as calcium oxalate (2). Although the incidence varies by age, sex, and geography, the clinical challenge of managing large, complex renal calculi remains consistent (3, 4).

The evolution of minimally invasive techniques has revolutionized the management of renal stones. Among them, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) has emerged as the gold-standard treatment for large renal stones (> 2 cm), offering high stone-free rates (SFRs) with reduced morbidity compared to open surgery (5-7). Since its inception, PCNL has been traditionally performed with the patient in the prone position, a practice rooted in historical precedent and surgical familiarity, providing a familiar anatomical field and ample working space (8).

However, the prone position is not without its significant physiological challenges. It is associated with alterations in cardiovascular and respiratory dynamics, including potential compromises to venous return, cardiac output, and pulmonary compliance due to thoracoabdominal compression (8, 9). These effects pose particular concerns for anesthesiologists, especially in patients with underlying cardiopulmonary comorbidities. In response, the supine position for PCNL has been introduced as a viable alternative, promising several practical advantages, such as easier airway management, the possibility of using spinal anesthesia, and obviating the need for laborious patient repositioning (10, 11).

Despite the growing interest, a definitive consensus on the optimal patient position for PCNL remains elusive. The current body of literature presents conflicting evidence. Recent meta-analyses and systematic reviews have sought to clarify this issue, with some indicating that supine PCNL is associated with a shorter operative time and reduced blood loss but may have a slightly lower SFR, while others report comparable efficacy and safety (12-14). This lack of clarity, particularly regarding objective, real-time intraoperative physiological parameters, underscores the need for rigorous comparative studies.

Furthermore, emerging evidence from other surgical disciplines reinforces the physiological impact of positioning. Studies in spine surgery have identified the prone position as an independent risk factor for intraoperative hypotension, generalizing this cardiovascular challenge beyond urology (15-17). Similarly, research in PCNL candidates has shown that strategic positioning after anesthesia can significantly influence hemodynamic stability and analgesic requirements, highlighting the critical role of posture in perioperative outcomes (18-20).

2. Objectives

This study was designed to conduct a detailed comparative analysis of intraoperative hemodynamic and respiratory parameters in patients undergoing PCNL in the prone and supine positions. By systematically evaluating blood pressure, heart rate (HR), oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO₂), we aimed to provide an evidence-based assessment of physiological stability, thereby informing the ongoing debate on patient positioning and contributing to enhanced safety and efficacy in PCNL practice.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

A retrospective comparative study was conducted at Namazi Hospital, affiliated with Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, after obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB No.: IR.SUMS.MED.REC.1401.058). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The medical records of all consecutive patients who underwent PCNL during a 12-month period from January 2023 to December 2023 were screened for eligibility.

3.2. Participants

A consecutive sampling method was used. During the study period, all eligible patients were assigned to either the supine or prone group based on the surgical position utilized for their procedure. This assignment was non-randomized, reflecting the retrospective and pragmatic nature of this cohort study.

Inclusion criteria were: Age greater than 18 years, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status of I or II, and the presence of renal pelvic stones measuring ≥ 2 cm, as confirmed by radiological imaging [kidney, ureter, and bladder (KUB) radiography or renal ultrasonography]. Exclusion criteria were applied to minimize confounding and included: Contraindications to the prone position, history of coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, renal impairment (serum creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL), ongoing hemodynamically active medication, renal anatomical anomalies such as horseshoe kidney, coagulopathies, pregnancy, immunodeficiency, ASA classification III or IV, or documented refusal to undergo supine positioning.

Forty adult patients meeting these criteria were included in the final analysis and divided equally into two groups: Supine (n = 20) and prone (n = 20).

3.3. Sample Size Calculation

An a priori sample size calculation was performed using G*Power software (Version 3.1.9.7), based on the primary outcome of intraoperative systolic blood pressure (SBP). Using data from a previous comparative study (19), which reported a mean difference (MD) of 6.8 mmHg (effect size d = 0.76) between supine and prone PCNL groups, a two-tailed independent samples t-test with an alpha of 0.05 and power of 0.80 required 27 patients per group (total N = 54). To account for potential attrition, we aimed to recruit 30 patients per group (N = 60). However, due to the retrospective nature of the study and the limited number of consecutive eligible cases within the 12-month period, the final analyzed cohort consisted of 40 patients (20 per group).

3.4. Surgical Technique and Anesthetic Management

All procedures were performed by a single, experienced endourologist to reduce inter-operator variability. A standardized general anesthesia protocol was applied to all patients. Anesthesia was induced with intravenous Sodium Thiopental (5 mg/kg), fentanyl (2 μg/kg), and atracurium (0.6 mg/kg). Maintenance was achieved using 0.5% halothane in a 50:50 mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen. It is acknowledged that halothane, a volatile agent with known myocardial depressive effects, was used; however, its use was standardized across both groups. Supplemental atracurium (0.2 mg/kg) was administered every 30 min. Neuromuscular blockade was reversed at the end of the procedure with neostigmine (0.04 mg/kg) and atropine (0.02 mg/kg).

Patients were mechanically ventilated in a volume-controlled mode. The ventilator parameters (tidal volume and respiratory rate) were set upon induction based on ideal body weight and were not adjusted intraoperatively in response to changes in ETCO₂ or patient position, as per the standardized protocol. This fixed-ventilation approach was intended to isolate the effect of patient position on respiratory parameters.

Intravenous fluid replacement was performed using Ringer's solution, and dextrose saline was provided postoperatively. Hypotension, defined as a reduction greater than 20% from baseline SBP, was managed by administration of boluses of Normal Saline or Ringer's solution. Glycine solution was used for continuous irrigation during PCNL. The total volume of irrigation fluid used and the effluent volume were recorded, and the absorbed fluid volume was calculated by subtraction.

3.5. Data Collection and Outcome Measures

Non-invasive blood pressure and pulse oximetry (Pooyandegane Rah Saadat Company, Model B5-SNTI/E2/M/C) were used to monitor the patients at baseline (pre-anesthesia), every 20 min intraoperatively, and immediately after anesthesia. Preoperative stone burden was evaluated using KUB radiography and renal ultrasonography.

The primary outcomes included intraoperative hemodynamic parameters [SBP and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and HR] and pulmonary function parameters (SpO₂ and ETCO₂). Secondary outcomes included perioperative hemoglobin levels (measured preoperatively and six hours postoperatively), total intraoperative fluid administration, anesthesia duration (defined as the time from induction of anesthesia to extubation), operative time (defined as the time from skin incision to skin closure), SFR (assessed by KUB radiography or non-contrast CT at three months), and perioperative complication rates (graded by the Clavien-Dindo classification).

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA). The normality of the distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and were compared between the supine and prone groups using independent samples t-tests. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages and were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

In addition to null hypothesis significance testing, effect sizes and their precision were calculated to provide a more comprehensive interpretation of results, which is particularly valuable given the sample size. For continuous variables, we reported the MD with 95% confidence intervals (CI). To quantify the standardized magnitude of the difference between groups, Cohen's d with a 95% CI was also calculated. For the single categorical variable (sex), the effect size was expressed as an odds ratio (OR) with a 95% CI. A two-tailed P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all the analyses. Crucially, no multivariate regression analysis was performed to adjust for potential confounders; therefore, all reported associations are unadjusted estimates.

4. Results

4.1. Participant Flow and Baseline Characteristics

A total of 40 patients who underwent PCNL within the study period were included in this retrospective analysis. Consecutive sampling was used to assign 20 patients to the supine group and 20 to the prone group based on the surgical position used during their procedure. As intended by our study design, the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the two cohorts were well-matched, with no statistically significant differences in age, sex, weight, renal function, preoperative hemoglobin, or stone size (all P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Variable | Supine Position | Prone Position | P-Value | Effect Size (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 47.3 ± 7.5 | 47.4 ± 9.1 | 0.967 | Cohen's d = -0.01 (-0.65 to 0.62) |

| Male sex | 9 (45) | 10 (50) | 0.752 | OR = 0.82 (0.24 to 2.79) |

| Weight (kg) | 73.4 ± 10.6 | 71.9 ± 12.2 | 0.671 | Cohen's d = 0.13 (-0.50 to 0.77) |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 15.4 ± 2.0 | 15.1 ± 3.6 | 0.782 | Cohen's d = 0.10 (-0.53 to 0.74) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.95 ± 0.16 | 0.98 ± 0.14 | 0.536 | Cohen's d = -0.20 (-0.84 to 0.43) |

| Pre-op hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 13.7 ± 1.3 | 0.745 | Cohen's d = -0.07 (-0.71 to 0.56) |

| Stone size (mm) | 33.6 ± 9.4 | 33.3 ± 12.9 | 0.93 | Cohen's d = 0.03 (-0.61 to 0.66) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval, OR, odds ratio.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD or No. (%).

b Participants were consecutively assigned to groups based on the surgical position used during the study period. Groups were well-matched for all key baseline variables (all P > 0.05).

4.2. Hemodynamic Parameters

The pre-anesthesia hemodynamic parameters were equivalent between the groups (Table 2). However, statistically significant intraoperative differences emerged. Starting from the first intraoperative measurement and persisting throughout the procedure, patients in the prone position exhibited significantly lower SBP and DBP alongside a markedly elevated HR compared with those in the supine position (all P < 0.001 at most time points).

| Time Point/ Parameters | Supine Position | Prone Position | P-Value | MD (95% CI) | Cohen's d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-anesthesia | |||||

| SBP (mmHg) | 128.5 ± 13.5 | 130.0 ± 13.8 | 0.73 | -1.50 (-10.22 to 7.22) | -0.11 (-0.75 to 0.53) |

| DBP (mmHg) | 80.0 ± 7.3 | 78.5 ± 7.5 | 0.523 | 1.50 (-3.22 to 6.22) | 0.20 (-0.44 to 0.85) |

| HR (bpm) | 75.0 ± 7.3 | 75.3 ± 7.9 | 0.917 | -0.25 (-5.04 to 4.54) | -0.03 (-0.67 to 0.60) |

| 20 min | |||||

| SBP | 116.5 ± 10.9 | 101.0 ± 11.7 | < 0.001 | 15.50 (8.36 to 22.64) | 1.38 (0.66 to 2.09) |

| DBP | 73.0 ± 6.2 | 63.5 ± 7.5 | < 0.001 | 9.50 (4.87 to 14.13) | 1.40 (0.68 to 2.11) |

| HR | 68.8 ± 6.0 | 77.5 ± 7.2 | < 0.001 | -8.75 (-13.08 to -4.42) | -1.31 (-2.04 to -0.57) |

| 40 min | |||||

| SBP | 126.5 ± 12.9 | 91.3 ± 10.2 | < 0.001 | 35.25 (27.96 to 42.54) | 3.02 (2.10 to 3.94) |

| DBP | 76.8 ± 7.3 | 54.8 ± 5.3 | < 0.001 | 22.00 (17.79 to 26.21) | 3.42 (2.43 to 4.41) |

| HR | 78.8 ± 6.7 | 100.0 ± 7.1 | < 0.001 | -21.25 (-25.78 to -16.72) | -3.10 (-4.06 to -2.14) |

| 60 min | |||||

| SBP | 128.5 ± 13.5 | 87.0 ± 7.9 | < 0.001 | 41.50 (34.29 to 48.71) | 3.70 (2.69 to 4.71) |

| DBP | 80.0 ± 7.3 | 49.8 ± 5.3 | < 0.001 | 30.25 (25.99 to 34.51) | 4.71 (3.52 to 5.90) |

| HR | 77.0 ± 6.4 | 105.3 ± 6.8 | < 0.001 | -28.25 (-32.53 to -23.97) | -4.29 (-5.35 to -3.23) |

| 80 min | |||||

| SBP | 133.3 ± 12.4 | 89.5 ± 4.6 | < 0.001 | 43.75 (37.41 to 50.09) | 4.59 (3.47 to 5.71) |

| DBP | 82.5 ± 4.4 | 52.3 ± 3.0 | < 0.001 | 30.25 (27.93 to 32.57) | 7.84 (5.91 to 9.77) |

| HR | 75.8 ± 3.4 | 114.8 ± 11.8 | < 0.001 | -39.00 (-44.62 to -33.38) | -4.52 (-5.61 to -3.43) |

| 100 min | |||||

| SBP | 129.0 ± 11.3 | 104.8 ± 11.1 | < 0.001 | 24.25 (17.23 to 31.27) | 2.16 (1.38 to 2.94) |

| DBP | 79.8 ± 3.4 | 63.0 ± 5.0 | < 0.001 | 16.75 (14.01 to 19.49) | 3.92 (2.85 to 4.99) |

| HR | 72.8 ± 6.6 | 104.5 ± 8.6 | < 0.001 | -31.75 (-36.80 to -26.70) | -4.10 (-5.12 to -3.08) |

| Post-anesthesia | |||||

| SBP | 125.8 ± 12.1 | 118.8 ± 12.1 | 0.08 | 7.00 (-0.88 to 14.88) | 0.58 (-0.07 to 1.23) |

| DBP | 78.3 ± 5.7 | 71.3 ± 5.8 | < 0.001 | 7.00 (3.18 to 10.82) | 1.22 (0.54 to 1.90) |

| HR | 74.0 ± 6.0 | 89.0 ± 6.2 | < 0.001 | -15.00 (-19.02 to -10.98) | -2.48 (-3.27 to -1.69) |

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; CI, confidence interval; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b All results are unadjusted estimates. The large magnitude of the Cohen's d effect sizes should be interpreted with caution given the modest sample size. Interpretation of Cohen's d: d < 0.2 = negligible; 0.2 ≤ d < 0.5 = small; 0.5 ≤ d< 0.8 = medium; d ≥ 0.8 = large.

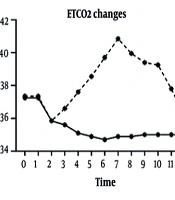

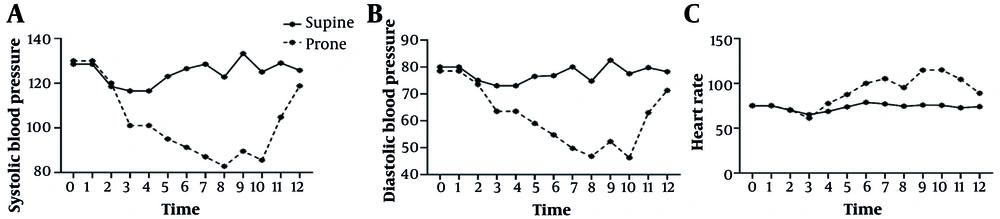

For instance, at the 80-minute mark — a representative point during sustained surgical activity — the mean SBP was 89.5 ± 4.6 mmHg in the prone group versus 133.3 ± 12.4 mmHg in the supine group (P < 0.001; Cohen's d = 4.59, 95% CI: 3.47 to 5.71). Similarly, HR peaked at 114.8 ± 11.8 bpm in the prone group compared to 75.8 ± 3.4 bpm in the supine group at the same interval (P < 0.001; Cohen's d = -4.52, 95% CI: -5.61 to -3.43). It is important to note that while these effect sizes are large, they are derived from a modest sample size and represent unadjusted estimates. These dynamic changes are visually summarized in Figure 1.

Trend of intraoperative hemodynamic parameters during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL); line graph illustrating the mean A, systolic blood pressure (SBP); B, diastolic blood pressure (DBP); and C, heart rate (HR) over time for patients undergoing PCNL in the supine (blue line) versus prone (red line) positions. Error bars represent standard deviation. The prone position was associated with a pronounced and sustained pattern of lower blood pressure and compensatory tachycardia throughout the procedure compared to the stable hemodynamic profile observed in the supine position (P < 0.001 at most time points). All data points represent unadjusted means (n = 20 per group).

4.3. Pulmonary Function Parameters

The pre-anesthesia pulmonary parameters were similar between the groups (Table 3). Intraoperatively, the prone position was associated with a consistent and statistically significant reduction in peripheral SpO₂ and an increase in ETCO₂ levels. While SpO₂ remained stable at 100% in the supine group throughout, it decreased in the prone group, reaching a nadir of 96.8 ± 1.3% at 40 minutes (P < 0.001; Cohen's d = 3.33, 95% CI: 2.33 to 4.33).

| Time Point/ Parameters | Supine Position | Prone Position | P-Value | MD (95% CI) | Cohen’s d (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-anesthesia | |||||

| SpO₂ | 99.5 ± 1.0 | 99.4 ± 0.8 | 0.723 | 0.10 (-0.47 to 0.67) | 0.11 (-0.51 to 0.73) |

| ETCO₂ (mmHg) | 37.3 ± 2.2 | 37.4 ± 2.4 | 0.891 | -0.10 (-1.56 to 1.36) | -0.04 (-0.66 to 0.58) |

| 20 min | |||||

| SpO₂ | 99.9 ± 0.4 | 97.4 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 | 2.55 (1.92 to 3.18) | 2.61 (1.76 to 3.46) |

| ETCO₂ | 35.6 ± 1.0 | 36.6 ± 1.7 | 0.027 | -1.00 (-1.88 to -0.12) | -0.70 (-1.33 to -0.07) |

| 40 min | |||||

| SpO₂ | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 96.8 ± 1.3 | < 0.001 | 3.25 (2.64 to 3.86) | 3.33 (2.33 to 4.33) |

| ETCO₂ | 35.1 ± 0.9 | 37.6 ± 1.5 | < 0.001 | -2.50 (-3.27 to -1.73) | -2.00 (-2.70 to -1.30) |

| 60 min | |||||

| SpO₂ | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 99.6 ± 0.8 | 0.012 | 0.45 (0.10 to 0.80) | 0.63 (0.14 to 1.12) |

| ETCO₂ | 34.7 ± 0.5 | 39.7 ± 1.5 | < 0.001 | -5.00 (-5.74 to -4.26) | -4.55 (-5.61 to -3.49) |

| 80 min | |||||

| SpO₂ | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 99.9 ± 0.4 | 0.075 | 0.15 (-0.02 to 0.32) | 0.43 (-0.04 to 0.90) |

| ETCO₂ | 34.9 ± 0.4 | 40.9 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 | -6.00 (-6.60 to -5.40) | -6.67 (-8.10 to -5.24) |

| 100 min | |||||

| SpO₂ | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 99.6 ± 0.6 | 0.005 | 0.40 (0.13 to 0.67) | 0.80 (0.24 to 1.36) |

| ETCO₂ | 34.9 ± 0.6 | 40.0 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 | -5.10 (-5.66 to -4.54) | -5.67 (-6.98 to -4.36) |

| Post-anesthesia | |||||

| SpO₂ | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 100.0 ± 0.0 | 1 | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) | 0.00 (0.00 to 0.00) |

| ETCO₂ | 35.0 ± 0.0 | 36.2 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 | -1.15 (-1.49 to -0.81) | -2.30 (-3.05 to -1.55) |

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; CI, confidence interval; SpO₂, oxygen saturation; ETCO₂, end-tidal carbon dioxide.

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Mechanical ventilation parameters were fixed and not adjusted intraoperatively for patient position.

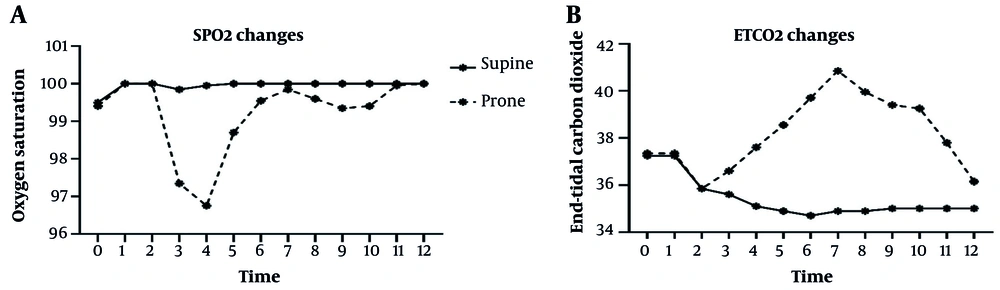

Concurrently, ETCO₂ in the prone group rose progressively, reaching a maximum of 40.9 ± 1.2 mmHg at 80 minutes, which was significantly higher than the stable 34.9 ± 0.4 mmHg maintained in the supine group (P < 0.001; Cohen's d = -6.67, 95% CI: -8.10 to -5.24). This pattern suggests a discernible impairment in ventilation and/or gas exchange during prone positioning. The trends for these parameters are shown in Figure 2. We note that mechanical ventilation parameters were fixed and not adjusted for position changes during the procedure, as per the standardized protocol.

Trend of intraoperative pulmonary function parameters during percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL); line graph illustrating the mean A, oxygen saturation (SpO₂); and B, end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO₂) over time for patients in the supine (blue line) and prone (red line) positions during PCNL. Error bars represent standard deviation. Patients in the prone position demonstrated a consistent trend of reduced oxygen saturation and elevated ETCO₂, suggesting impaired gas exchange compared to the stable respiratory parameters maintained in the supine position (P < 0.001 at most time points). All data points represent unadjusted means (n = 20 per group). Ventilator settings were fixed and not adjusted for position.

4.4. Operational and Safety Outcomes

There was no significant difference in the decline in hemoglobin levels pre- and postoperatively between the groups (P = 0.197). However, the volume of intraoperative fluid replacement was significantly higher in the prone group (1950.0 ± 484.0 mL vs. 1475.0 ± 472.3 mL, P = 0.003), indicating a greater need for resuscitation to maintain hemodynamic stability.

Furthermore, the total anesthesia duration (from induction to extubation) was substantially longer for patients in the prone position than for those in the supine position (158.3 ± 25.0 min vs. 118.3 ± 18.3 min, P < 0.001). In contrast, the pure operative time (from skin incision to closure) was not statistically different (115.5 ± 22.1 min prone vs. 105.8 ± 16.5 min supine, P = 0.118). This disparity suggests that the increased anesthesia duration in the prone group is attributable to logistical factors such as patient repositioning and potentially more complex airway management, rather than to the surgical procedure itself.

4.5. Stone-Free Rate and Postoperative Complications

The SFR, assessed at the 3-month follow-up via imaging, was comparable between the two groups. The prone and supine position groups achieved SFRs of 95.1% and 94.5%, respectively (P > 0.05). With respect to postoperative safety, no serious adverse events (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III) were reported in either group during hospitalization.

Analysis of minor complications (Clavien-Dindo grade I-II) revealed a higher, though not statistically significant, incidence in the prone group. Specifically, low-grade fever was observed in two patients (10%) in the prone group compared to one patient (5%) in the supine group, all of which resolved promptly with standard antibiotic therapy.

5. Discussion

This comparative study offers a comprehensive evaluation of the physiological implications of patient positioning during PCNL. Our principal finding indicates that the supine position provides significantly greater intraoperative stability, as evidenced by improved hemodynamic parameters, enhanced respiratory mechanics, lower fluid requirements, and reduced anesthesia duration compared with the conventional prone position. These insights add valuable empirical evidence to the ongoing discourse on the optimal positioning strategy in PCNL, with direct relevance to enhancing perioperative safety.

Despite the predominance of the prone approach in PCNL, the introduction of various supine modifications has reignited the debate regarding optimal patient positioning. Supine positioning offers advantages, such as a reduced risk of position-related injuries and potentially decreased operative times, particularly in patients with cardiorespiratory compromise. It is increasingly recognized as a safe and effective alternative, particularly for those with comorbidities, although surgical expertise remains a decisive factor in method selection and outcomes (9, 12-14, 21-23).

In our study, the pronounced hemodynamic instability observed in the prone group, characterized by significant and sustained hypotension accompanied by reflex tachycardia, is consistent with the established physiological effects of prone positioning. The mechanical compression of the abdomen and thorax in this posture impedes venous return and elevates intrathoracic pressure, thereby reducing cardiac preload and leading to hypotension (24, 25). Our findings are strongly supported by recent, large-scale evidence from other surgical disciplines. For instance, a study in spine surgery identified the prone position as an independent predictor of intraoperative hypotension, generalizing this cardiovascular challenge beyond urological procedures (16, 20). Furthermore, studies on PCNL candidates have demonstrated that strategic positioning after spinal anesthesia significantly affects hemodynamic stability and opioid requirements, highlighting posture's critical role in perioperative management (18-20, 25).

Our results concur with those of Khoshrang et al. and Roodneshin et al., who similarly reported increased hemodynamic fluctuations and elevated HRs among patients placed in the prone position (19, 26). In contrast, the supine position avoids such compartmental compression, maintaining a more physiological and stable cardiovascular state, which may alleviate anesthetic challenges and reduce the risk of organ hypoperfusion (27, 28).

Moreover, our study highlighted a clear decline in respiratory function associated with prone positioning during PCNL. The consistent elevation in (ETCO₂ and reduction in SpO₂ suggest impaired ventilation and gas exchange, likely due to restricted diaphragmatic excursion and increased airway pressure induced by thoracoabdominal compression (29). While a key methodological limitation is the absence of arterial blood gas analysis (PaO₂, PaCO₂) to definitively confirm these findings, the persistent and statistically significant trends we observed are strongly indicative of compromised respiratory mechanics in the prone position. Conversely, patients in the supine position maintained stable respiratory parameters throughout the procedure, underscoring the advantage of this position in preserving pulmonary function. This observation aligns with the work of Erdal et al., who demonstrated that oxygenation deteriorates during prolonged prone positioning but improves when patients are returned to the supine position (25).

It is important to contextualize these findings within the broader literature, which presents some variability. For instance, Erdal et al. also noted significant postoperative impairments in blood gas parameters for both positions, while Hokenek et al. reported differing results regarding respiratory outcomes (25, 30). Nevertheless, the predominant physiological evidence and the intraoperative stability observed in our cohort favor the respiratory benefits of the supine position. This consideration is especially relevant for patients with pre-existing pulmonary comorbidities, where minimizing intraoperative respiratory compromise is essential.

In our analysis, anesthesia duration was significantly prolonged in the prone cohort than in the supine group, corroborating prior studies (9, 25, 31, 32). This difference is likely attributable to the logistical complexities of prone positioning, including the time required for careful patient repositioning after anesthesia induction and the greater challenges in airway management, rather than the surgical procedure itself, as operative times were comparable. Although the surgical procedure duration and irrigation fluid volume did not differ substantially between the groups, a tendency toward increased values in prone patients was noted, consistent with the existing literature (12). The supine position offers practical intraoperative advantages, including eliminating the need for patient repositioning, facilitating anesthetic management, and providing quicker airway access (9, 33-35). These factors likely contributed to the shorter anesthesia duration observed in the supine group.

Beyond the core physiological parameters, our study revealed operationally relevant differences. The greater volume of fluid required to maintain hemodynamic stability in prone patients underscores the physiological challenge posed by this position. Similarly, the prolonged anesthesia duration in prone PCNL, validated by multiple investigations (10, 30, 35), reflects increased resource utilization and potential patient risks. Comparable SFRs and hemoglobin decline between groups affirm that patient positioning does not compromise the efficacy or safety of stone removal, a conclusion supported by recent meta-analyses (36). However, it is important to contextualize this finding, as another meta-analysis found a significantly lower SFR for the supine position (14), highlighting that surgical efficacy may be influenced by multiple factors, including surgeon experience and stone complexity.

Compared to Batratanakij et al. (35), who reported significantly higher postoperative infection rates in the prone position, our study found no serious complications (Clavien-Dindo grade ≥ III) in either group and only a non-significant increase in minor complications such as low-grade fever. The difference may reflect variations in sample size, patient characteristics, surgeon experience, or perioperative protocols, underscoring the influence of contextual factors on clinical outcomes. Batratanakij et al. identified prone positioning and positive preoperative urine cultures as independent risk factors for infection, likely due to increased bacterial endotoxin release during stone fragmentation and impaired clearance from thoracoabdominal compression in the prone position (35). Our findings of stable vital signs and laboratory parameters support the overall safety of both approaches when combined with prophylactic antibiotics and vigilant monitoring. Nonetheless, the higher infection and pleural complication rates in the prone group reported by others (35), emphasize the potential respiratory and infectious advantages of the supine position, aligning with the growing body of physiological and clinical evidence.

5.1. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that supine positioning during PCNL may offer superior intraoperative physiological stability compared to the traditional prone approach in selected patients. The supine position was associated with more stable hemodynamics, improved pulmonary function, reduced fluid requirements, and shorter anesthesia duration, without compromising short-term surgical efficacy or safety. These physiological and practical advantages suggest that supine PCNL represents a preferable and reliable option for many patients, particularly those with cardiorespiratory comorbidities or those for whom rapid anesthetic turnover is beneficial.

However, as outlined in the limitations, these conclusions are drawn from a preliminary, single-center retrospective cohort and must be interpreted with caution. Therefore, our findings require validation through larger, multicenter, randomized controlled trials that incorporate standardized, contemporary anesthetic protocols, advanced physiological monitoring (including arterial blood gases), and long-term follow-up to assess comprehensive clinical outcomes.

Surgeon expertise remains a critical determinant of success. Nevertheless, based on the accumulating evidence including this study, the supine technique should be considered a viable and often advantageous primary approach. Adopting this position aligns surgical practice with the fundamental goal of minimizing physiological disturbance and enhancing patient-centered perioperative care. Future research should focus on identifying which patient subgroups derive the greatest benefit from supine positioning, further optimizing the technique to improve its accessibility and outcomes across diverse clinical settings.

5.2. Study Limitations and Strengths

The primary strengths of this study include the use of a standardized surgical and anesthetic protocol, with all procedures performed by a single surgeon, significantly reducing inter-operator variability and enhancing the internal consistency of the comparative data. However, several important limitations must be acknowledged to contextualize our findings. First, the retrospective, non-randomized, single-center design inherently introduces the potential for selection bias and unmeasured confounding, despite our efforts to match groups on key baseline variables. The modest sample size of 40 patients, while sufficient to detect the large effect sizes reported for our primary outcomes, may have limited the power to identify more subtle differences in secondary endpoints and increases the risk of type II error. The large Cohen’s d values observed should therefore be interpreted with caution, as effect sizes can be inflated in smaller studies.

Methodologically, we did not perform multivariate regression analysis to adjust for potential confounders such as subtle differences in fluid therapy or depth of anesthesia; consequently, all reported associations are unadjusted estimates. The use of halothane, an anesthetic agent with known myocardial depressive effects, is another notable limitation. While its use was standardized across both groups, it may have potentiated the hemodynamic instability observed in the prone position, and findings may not be directly generalizable to settings using contemporary volatile agents.

Furthermore, the absence of arterial blood gas analysis (PaO₂, PaCO₂) restricts a more definitive assessment of respiratory function and gas exchange, relying instead on surrogate markers (SpO₂ and ETCO₂). The lack of long-term follow-up beyond three months limits our evaluation of delayed complications or recurrent stone events. Finally, the generalizability of our findings may be confined to settings with similar patient populations, surgical expertise, and anesthetic practices. The favorable outcomes in the supine group may partly reflect our surgical team’s specific proficiency with this approach.