1. Background

As a glycopeptide antibiotic, vancomycin is primarily effective against Gram-positive bacteria. It is particularly important for the treatment of infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (1, 2). However, vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity is a well-documented adverse effect, occurring in approximately 5 - 25% of patients (3, 4). Nephrotoxicity is a potential side effect associated with vancomycin, primarily mediated by the generation of free radicals and reactive oxygen species (ROS) (5, 6). The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI) or vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity can range from 9.34 to 36.4% 3, which is a high rate demanding timely preventive measures (5, 7).

Vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity is a significant concern in clinical practice, particularly in patients receiving high doses or prolonged therapy. Several risk factors have been identified that can accelerate or potentiate the development of this adverse effect, including high vancomycin trough levels, high vancomycin doses, concomitant antibiotic therapy, prolonged antibiotic course, and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) (8). In the search for potential nephroprotective agents, theophylline has emerged as a candidate due to its mechanism of action.

On the other hand, theophylline is an oral methylxanthine bronchodilator primarily used in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). It is often considered as an alternative therapeutic option for these conditions (9). It has also been utilized as a prophylactic treatment in infants who have experienced a perinatal hypoxic-ischemic event to enhance the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), with the intended effect of reducing blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine levels (10, 11). Theophylline has been shown to prevent AKI in infants caused by asphyxia without increasing the risk of mortality (12), and it is also used to prevent AKI. Due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, as well as its ability to inhibit kidney vessel vasoconstriction, theophylline is believed to mitigate the adverse effects of vancomycin on kidney tubules (13), and plays a prophylactic role against vancomycin-induced nephropathy (14). Previous studies have demonstrated that a single dose of theophylline, administered as a prophylactic treatment in neonates with asphyxia, can partially reduce the risk of AKI (15). A 2019 study demonstrated the antioxidant properties of theophylline (16). In a systematic review, Bagshaw and Ghali suggested that theophylline may have a potential role in reducing the risk of contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) (3). The pathophysiology of CIN involves hypoxic injury to the renal medulla. Notably, the mechanisms of renal hypoxic injury and oxidative stress in CIN share significant similarities with the proposed mechanisms of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity.

Moreover, while the majority of prior research has focused on the impact of theophylline on AKI in infants following asphyxia, limited attention has been given to its potential role in preventing nephropathy associated with hypernatremic dehydration. Existing studies suggest that theophylline, when administered in low doses, may mitigate the reduction in GFR induced by hypoxemia (16). However, it remains controversial whether treatment with theophylline, as an adenosine antagonist, can prevent drug-induced nephrotoxicity.

2. Objective

The present study was designed to investigate the potential protective effects of theophylline against AKI, particularly vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity. The primary objective of this trial was to determine whether adjunctive theophylline administration reduces the incidence of vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity, as measured by changes in urinary microalbumin, BUN, and eGFR, in a pediatric population. A formal, standardized clinical definition of AKI (e.g., KDIGO criteria based on serum creatinine or urine output) was not applied as a primary endpoint.

3. Methods

This single-blind randomized clinical trial included children and adolescents aged 1 month to 18 years who were undergoing vancomycin treatment for systemic infections at Sabzevar Heshmatieh Hospital in Iran. The study was prospectively registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT20220326054351N1) and received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences (IR.MEDSAB.REC.1400.138). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participants before enrollment. Patient information was collected through medical records. The sample size was calculated based on a previous study investigating aminophylline in vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity (5). Assuming an effect size (Cohen's d) of 0.7 for the primary outcome (microalbumin), with an alpha of 0.05 and power of 80%, a minimum of 34 patients per group was required.

3.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This study enrolled 68 patients who were randomly assigned to two groups: An intervention group (34 patients) and a control group (34 patients). Eligible participants were aged between one month and 18 years and had completed a 10-day course of vancomycin as part of their treatment, based on the clinical judgment of the attending physician. Exclusion criteria included lack of parental or guardian consent, pre-existing renal or kidney disease, the development of unpredictable complications or side effects during treatment, transfer to another hospital before completing the 10-day therapy, or discharge from the hospital before finishing the 10-day treatment regimen.

3.2. Group Allocation

This single-blind, two-arm randomized clinical trial enrolled patients receiving vancomycin for systemic infections at Heshmatieh Hospital in Sabzevar. A total of 68 participants were included in the study after providing written informed consent and meeting predefined eligibility criteria. The trial aimed to compare the efficacy and safety of two different treatment regimens or interventions in the management of systemic infections requiring vancomycin therapy. Given the heterogeneity of the study population (age range 1 month-18 years, diverse diagnoses, and care settings), subgroup analyses were not performed due to sample size constraints; this heterogeneity is acknowledged as a limitation.

3.3. Randomization and Blinding

Participants were randomly allocated to two groups through permuted block randomization with a block size of 4 (17), using a computer-generated sequence. The allocation sequence was concealed from the enrolling researchers using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (SNOSE). Patients in Group T received vancomycin combined with adjunctive oral theophylline (10 mg/kg/day, divided into two 12-hour doses, administered as an oral syrup). The theophylline was initiated concurrently with vancomycin and was administered for the entire 10-day vancomycin course. The theophylline dosage was determined based on prior safety data, ensuring that peak serum levels remained below the maximum safe threshold of 12 - 14 mg/L (not mg/kg/day) (18, 19). The dose of 10 mg/kg/day was selected as a conservative, prophylactic regimen to minimize the risk of adverse events in a pediatric population, acknowledging that it is lower than typical loading doses used for bronchodilation. Dosing was adjusted based on participant body weight alone; no dose adjustments were made for age or renal function during the study period. Notably, serum levels of neither vancomycin nor theophylline were monitored, which limits the interpretation of exposure-response relationships and safety margins.

Vancomycin dosing was administered according to standard protocols (15 mg/kg every 6 hours) and adjusted based on renal function as necessary. Both the treatment and control groups received medications for 10 days. This was a single-blind study; outcome assessors and data analysts were blinded to group assignments. Clinicians and participants were not blinded to the treatment due to the nature of the intervention. This introduces a potential for performance bias, as unblinded clinicians could have influenced supportive care (e.g., hydration, monitoring intensity), though all patients received standard institutional care protocols.

3.4. Outcome Assessment

The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the Schwartz formula. Urine and blood samples were collected at 8 a.m. at baseline, day 3, day 10, and day 30 post-treatment. Urine samples were analyzed for microalbuminuria, a marker of tubular injury, measured as urinary microalbumin concentration without simultaneous creatinine measurement for calculation of an albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). Blood samples were assessed for serum urea and creatinine levels.

Urinary microalbumin levels were measured using the Q-LINE BIOTECH Microalbumin Kit, with a normal range defined as less than 30 mg/g creatinine or less than 30 mg/24 hours. Blood urea nitrogen levels were determined using the Stress Marq BUN Detection Kit, with a normal range of approximately 5 - 18 mg/dL (1.8 - 6.4 mmol/L) in children. Serum creatinine levels were measured using the FUJIFILM Wako Creatinine Kit, with normal ranges varying by age and muscle mass:

- Infants (0 - 1 year): 0.2 - 0.4 mg/dL (18 - 35 µmol/L)

- Children (1 - 12 years): 0.3 - 0.7 mg/dL (27 - 62 µmol/L)

- Adolescents (13 - 18 years): 0.5 - 1.0 mg/dL (44 - 88 µmol/L)

These time points were selected based on evidence indicating delayed changes in creatinine and urea levels (> 72 hours post-nephrotoxic insult). Laboratory personnel responsible for sample analysis were blinded to group assignments.

3.5. Safety Monitoring

Adverse events related to theophylline were actively monitored throughout the study period. Clinicians assessed participants daily for signs of theophylline toxicity, including gastrointestinal distress (nausea, vomiting), central nervous system effects (insomnia, headache, tremors, seizures), and cardiovascular effects (tachycardia, arrhythmias, hypotension). Any suspected adverse event was documented in the medical record.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis, with missing data imputed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. A per-protocol (PP) analysis was also performed for sensitivity. In the PP analysis, participants who discontinued the study before day 10 were replaced with newly enrolled patients meeting the same eligibility criteria to preserve sample size; the potential for bias introduced by this replacement strategy is acknowledged. Quantitative data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, while nominal data are presented as frequencies. For statistical comparisons, the independent t-test was used for normally distributed data, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed data. The normality of data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical data were compared using the chi-square test. For longitudinal analysis, repeated-measures ANOVA was employed. The assumption of sphericity was tested using Mauchly's test; when violated, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. Results are reported with corrected degrees of freedom and p-values where applicable.

4. Results

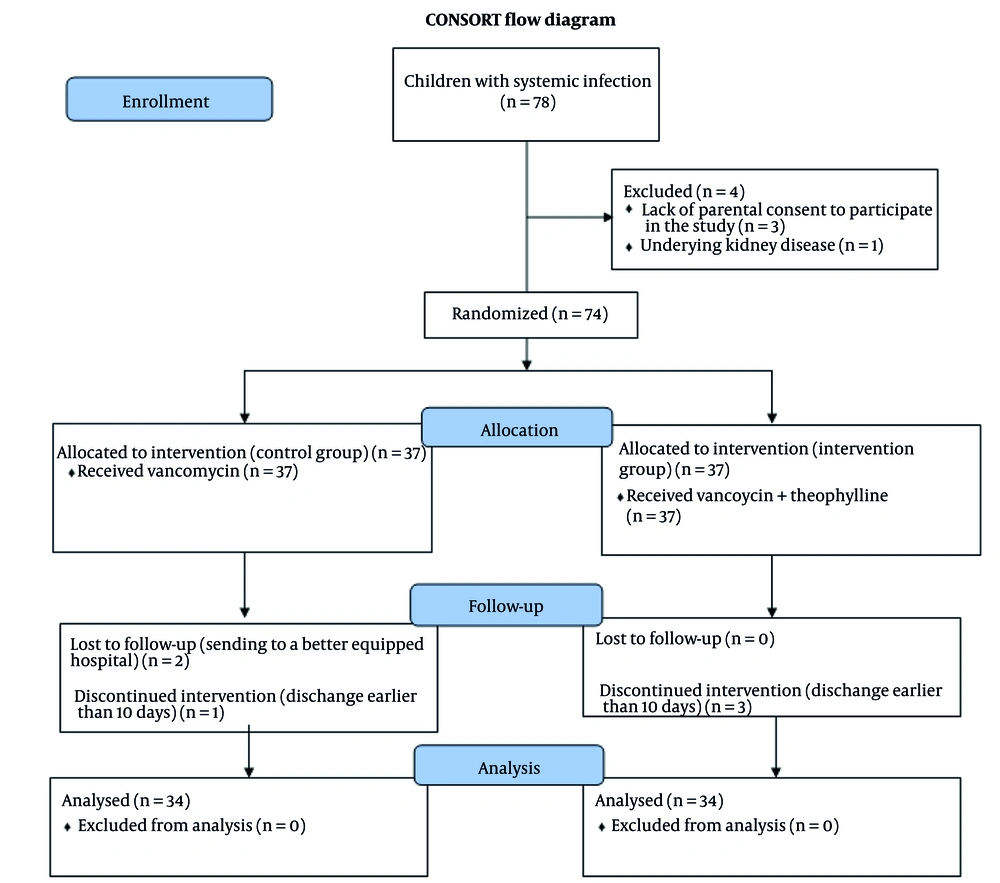

The CONSORT flowchart depicting the study design and participant flow is shown in Figure 1. Three children in the intervention group and one child in the control group were excluded from the per-protocol analysis due to early discharge (before completing the 10-day study period). Furthermore, two children in the control group required transfer to tertiary care centers for specialized treatment. To preserve the sample size for the per-protocol analysis, each excluded participant was replaced. This replacement strategy may introduce selection bias and is a limitation of the PP analysis. For sensitivity, an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was also performed using the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method, which produced results consistent with the per-protocol analysis presented here. To maintain statistical power for the per-protocol analysis, participants who dropped out were replaced by newly enrolled patients meeting the same eligibility criteria; they were not matched on specific characteristics beyond the study's inclusion criteria.

Twenty-three critically ill patients were admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), while the remaining patients were cared for in the pediatric ward. Among these, 15 were diagnosed with sepsis, 9 with central line infections, and 13 with bacteremia. Other conditions included severe pneumonia in 13 patients, meningitis in 10, and complications from abdominal surgery in 8 (Table 1).

| Diagnosis | Group C | Group T |

|---|---|---|

| Sepsis | 8 | 7 |

| Bacteremia | 4 | 9 |

| C. L. infection | 6 | 3 |

| Meningitis | 7 | 3 |

| Severe pneumonia | 5 | 8 |

| Abdominal surgery | 4 | 4 |

a Group T received theophylline and vancomycin simultaneously, while Group C received vancomycin only.

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

The study enrolled 68 pediatric patients ranging in age from 2 months to 14 years. The mean age of the control group was 4.8 ± 3.5 years, compared to 5.6 ± 4 years in the intervention group, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.435). Gender distribution was balanced, with 36 males (52.9%) and 32 females (47.1%), and no significant difference was observed between the control and intervention groups (P = 1.000). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in weight between the control group (17.97 ± 9.50 kg) and the intervention group (20.03 ± 10.19 kg) (P = 0.541) (Table 2).

| Time of Evaluation | Group C | Group T | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 4.8 ± 3.5 | 5.6 ± 4 | 0.435 |

| Gender (male/female) | (52.9/47.1) | (52.9/47.1) | 1.000 |

| Weight | 17.97 ± 9.50 | 20.03 ± 10.19 | 0.541 |

| Height | 104.5 ± 29 | 111.2 ± 28.2 | 0.347 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD unless indicated.

b Group T received theophylline and vancomycin simultaneously, while Group C received vancomycin only.

4.2. Comparison of Mean Urinary Microalbumin Levels Between Intervention and Control Groups

The baseline urinary microalbumin levels were comparable between the two groups before the intervention, with no significant difference observed. This finding is supported by the Mann-Whitney test results (P = 0.701), indicating that the intervention did not have a measurable effect on microalbumin levels (Table 3).

| Time of Evaluation | Group C | Group T | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | 6.25 ± 4.21 | 5.64 ± 4.53 | 0.701 |

| The 3rd day | 5.95 ± 4.30 | 4.90 ± 4.35 | 0.366 |

| The 10th day | 7.82 ± 3.14 | 5.12 ± 2.42 | 0.023 |

| The 30th day | 6.43 ± 2.56 | 5.01 ± 1.12 | 0.048 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Group T received theophylline and vancomycin simultaneously, while Group C received vancomycin only.

The mean urinary microalbumin levels on the 3rd, 10th, and 30th days post-treatment for the intervention and control groups were as follows: (5.95 ± 4.30 mg/L vs. 4.90 ± 4.35 mg/L, P = 0.366), (5.12 ± 2.42 mg/L vs. 7.82 ± 3.14 mg/L, P = 0.023), and (5.01 ± 1.12 mg/L vs. 6.43 ± 2.56 mg/L, P = 0.048), respectively. The intervention group exhibited lower urinary microalbumin levels than the control group at all post-treatment time points. While the difference on day 3 was not statistically significant, the reductions in the intervention group became significant on days 10 and 30, as demonstrated by the results of the Mann-Whitney U test (Table 3). All measured microalbumin values remained within the normal reference range (< 30 mg/g creatinine), indicating that the observed changes, while statistically significant, may not represent clinically overt kidney injury.

A within-group analysis showed that urinary microalbumin significantly increased from baseline to day 10 in the control group (P = 0.015), whereas no significant change was observed in the intervention group (P = 0.421).

4.3. Comparison of Mean Blood Urea Nitrogen Levels Between Intervention and Control Groups

Furthermore, the mean baseline BUN level (before the intervention) was 13.41 ± 3.44 mg/dL in the control group and 13.47 ± 2.18 mg/dL in the intervention group. An independent t-test revealed no statistically significant difference between the groups (P = 0.954) (Table 4).

| Time of Evaluation | Group C | Group T | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | 13.41 ± 3.44 | 13.47 ± 2.18 | 0.954 |

| The 3rd day | 12.75 ± 4.71 | 10.23 ± 3.50 | 0.683 |

| The 10th day | 16.07 ± 5.13 | 13.65 ± 3.61 | 0.031 |

| The 30th day | 16.98 ± 4.32 | 12.96 ± 3.78 | 0.045 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Group T received theophylline and vancomycin simultaneously, while Group C received vancomycin only.

Additionally, the mean BUN levels on the 3rd, 10th, and 30th days post-treatment for the intervention and control groups were as follows: (12.75 ± 4.71 mg/L vs. 10.23 ± 3.50 mg/L, P = 0.683), (13.65 ± 3.61 mg/L vs. 16.07 ± 5.13 mg/L, P = 0.031), and (12.96 ± 3.78 mg/L vs. 16.98 ± 4.32 mg/L, P = 0.045), respectively. Blood urea nitrogen levels were consistently lower in the intervention group compared to the control group after treatment. Significant between-group differences were found on days 10 and 30 (Table 4).

4.4. Comparison of the Mean Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate Level of Patients in the Intervention and Control Groups

The mean baseline eGFR was 87.2 ± 24.2 in the control group and 90.7 ± 25.3 in the intervention group, showing no significant difference (P = 0.564) as per the independent t-test. This indicates that the intervention did not have a statistically meaningful impact on eGFR compared to the control (Table 5).

| Time of Evaluation | Group C | Group T | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before treatment | 87.2 ± 24.2 | 90.7 ± 25.3 | 0.564 |

| The 3rd day | 89.5 ± 22.7 | 95.5 ± 22.7 | 0.282 |

| The 10th day | 85.7 ± 24 | 99.4 ± 19.3 | 0.016 |

| The 30th day | 87.1 ± 25.2 | 98.7 ± 19.4 | 0.039 |

a Values are expressed as mean ± SD.

b Group T received theophylline and vancomycin simultaneously, while Group C received vancomycin only.

After treatment, eGFR levels were evaluated on the 3rd, 10th, and 30th days for both groups. In the intervention group, the eGFR values were 95.5 ± 22.7, 99.4 ± 19.3, and 98.7 ± 19.4 mL/min/1.73m² on days 3, 10, and 30, respectively. In contrast, the control group recorded values of 89.5 ± 22.7, 85.7 ± 24.0, and 87.1 ± 25.2 mL/min/1.73m². Estimated glomerular filtration rate was higher in the intervention group at all post-treatment assessments. While the difference on day 3 was not significant, the intervention group demonstrated significantly higher eGFR than the control group on days 10 and 30 (Table 5).

4.5. Longitudinal Analysis of Primary Outcomes

A repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted to evaluate the effect of theophylline on urinary microalbumin, BUN, and eGFR over time (baseline, day 3, day 10, day 30). Mauchly's test indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated for all three outcomes; therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied. The analysis revealed a statistically significant interaction between group and time for urinary microalbumin [F (3, 186) = 4.12, P = 0.007, partial η² = 0.062], BUN [F (3, 186) = 3.58, P = 0.015, partial η² = 0.055], and eGFR [F (3, 186) = 3.95, P = 0.009, partial η² = 0.060]. This indicates that the changes over time in these parameters were significantly different between the intervention and control groups (Table 6).

| Dependent Variable | F-Statistic | Degrees of Freedom (df) | P-Value | Partial Eta Squared (η²ₚ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urinary Microalbumin | 4.12 | (3, 186) | 0.007 | 0.062 |

| BUN | 3.58 | (3, 186) | 0.015 | 0.055 |

| eGFR | 3.95 | (3, 186) | 0.009 | 0.060 |

Abbreviations: BUN, blood urea nitrogen levels; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

4.6. Safety Outcomes

No adverse events attributable to theophylline administration were reported during the study period. Specifically, there were no documented cases of gastrointestinal distress, insomnia, tremors, seizures, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, or other signs of theophylline toxicity.

5. Discussion

Vancomycin is associated with an increased risk of kidney impairment, with reported nephrotoxicity rates ranging from 5% to 35%. Prolonged use, especially beyond seven days, significantly elevates the likelihood of these adverse effects (20).

Understanding the mechanisms underlying vancomycin-associated nephrotoxicity is crucial for developing effective preventive strategies. Current research suggests that nephrotoxicity may arise from factors such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammatory pathways, underscoring the importance of continued investigation in this field (5). However, the precise mechanism remains unclear.

Theophylline has been studied for its potential to mitigate vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity and reduce the incidence of AKI associated with vancomycin use (21). However, clinical guidelines recommend exercising caution when using it for the prevention of AKI.

The maximum safe dose of theophylline is 12 to 14 mg/kg. However, due to its extremely narrow therapeutic window, a dose of 10 mg/kg/day, divided into two administrations, was prescribed in this study to minimize the risk of toxicity (22). No adverse effects were observed through active clinical monitoring. Additionally, severe side effects like nausea, vomiting, cardiac arrhythmias, hypotension, and convulsions were not reported during the treatment (23). Theophylline has been investigated in numerous studies for its potential to prevent nephrotoxicity, including CIN, with varying outcomes. In this study, a safe and conservative dose of theophylline was used to evaluate its effects.

Results showed that the average microalbumin levels on the third day post-intervention were lower in the intervention group compared to the control group, though this difference was not statistically significant. However, by the 10th and 30th days, the differences between the groups became statistically significant. Importantly, all microalbumin values remained within the normal range, suggesting the observed effect may represent a modulation of subclinical renal stress rather than prevention of overt AKI. Blood urea nitrogen levels levels increased in the control group, while eGFR remained stable in the control group and showed an increase in the treatment group. The changes in the intervention group were more pronounced, with statistically significant reductions observed on the 10th and 30th days, in contrast to the 3rd day, where no significant changes were noted.

The results indicate that theophylline did not significantly affect eGFR, BUN, or microalbumin levels compared to the control group on the third day. However, significant differences between the two groups emerged after the 10th and 30th days of theophylline administration, suggesting a delayed response in kidney function markers to theophylline treatment. The positive eGFR results observed 30 days post-treatment prompted further investigation. On the other hand, the positive eGFR results observed 30 days post-treatment prompted further investigation.

Previous trials and meta-analyses investigating the use of the adenosine antagonist theophylline have produced inconsistent findings, with the majority of research conducted on animal models, particularly rats (18, 19). Some studies have investigated the protective effects of a single dose of theophylline in cases of neonatal asphyxia. Building on this evidence, we conducted the present study to assess the potential prophylactic effect of theophylline on vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity.

Similarly, Bhatt et al. investigated the role of theophylline and aminophylline in preventing AKI in children. They found that a single dose of theophylline as prophylaxis in neonatal asphyxia significantly reduced the risk of AKI and severe kidney dysfunction (15).

Azizi et al. demonstrated that theophylline exerts a protective effect against kidney dysfunction and reduces the risk of AKI in neonates with asphyxia. In cases of asphyxia-induced tubular hypoxemia, vasoconstriction occurs, leading to elevated adenosine levels. Similarly, vancomycin can induce renal vasoconstriction and increase adenosine levels, thereby reducing renal blood flow and decreasing the GFR. The vasoconstrictive effects of adenosine can be mitigated by adenosine antagonists, such as theophylline, which block its action (24, 25).

Vancomycin is known to induce oxidative stress in kidney tubules, resulting in impaired mitochondrial function and disrupted tubular reabsorption. Theophylline, acting as an adenosine antagonist, has been shown to exert protective effects against this oxidative stress and renal vasoconstriction (26). While our study was not designed to elucidate the precise mechanism, the observed renoprotection is consistent with the proposed pathways of adenosine antagonism and antioxidant activity, as cited in previous literature (3, 13, 15). Future studies should include biomarkers for oxidative stress and renal blood flow to directly test these hypotheses.

Wu et al. emphasized the antioxidant properties of theophylline and theobromine, underscoring their potential to mitigate oxidative stress. Numerous studies have corroborated the ability of these compounds to reduce the production of ROS, further supporting their therapeutic benefits (16). Similarly, our results suggest that theophylline demonstrates antioxidant properties and may be effective in mitigating vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity. In a systematic review, Bagshaw and Ghali investigated the role of theophylline in preventing CIN and identified evidence supporting its potential efficacy in reducing CIN, particularly in moderate- to high-risk patients undergoing coronary angiography or angioplasty (3). The pathophysiology of CIN involves hypoxic injury to the renal medulla, driven by three interconnected mechanisms: The hemodynamic effects of contrast media (CM), the production of ROS and free radicals, and the direct cytotoxic effects of CM molecules on tubular cells (27). Notably, the mechanisms underlying CIN and vancomycin-induced nephrotoxicity exhibit significant similarities, and the protective role of theophylline in both conditions is well-documented.

In our study, the control group demonstrated a progressive increase in BUN and microalbumin levels, along with a decline in eGFR over time. In contrast, the theophylline treatment group exhibited significant improvements in these parameters throughout the 30-day observation period (P < 0.05).

5.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. The primary limitation is the small sample size, which restricts the generalizability of the findings and underscores the need for further validation through larger, more robust clinical trials. These trials should prioritize clinically relevant outcomes such as KDIGO-defined AKI to better elucidate theophylline's potential in preventing vancomycin-induced AKI. Additionally, the clinical safety of theophylline across various dosing regimens requires comprehensive evaluation before any reconsideration of its use in clinical practice. Another significant limitation was the inability to measure vancomycin and theophylline levels at this center, which could have provided valuable insights into their pharmacokinetic interactions and potential dose-response relationships. We have now explicitly stated the lack of pharmacokinetic monitoring as a major limitation in the Discussion. Furthermore, the study did not assess the ratio of microalbumin to creatinine, a more sensitive and reliable index for detecting early kidney injury. Although microalbumin levels decreased in the intervention group, they remained within the normal range, limiting the ability to draw definitive conclusions about theophylline's renoprotective effects. The clinical significance of the observed biomarker changes therefore remains uncertain. Furthermore, the single-blind design where clinicians were not blinded could have introduced potential for performance bias, although outcome assessors were blinded. Although an ITT analysis supported our findings, the replacement of dropouts in the per-protocol analysis is a methodological limitation that may introduce bias. These limitations highlight the need for more rigorous and detailed investigations in future studies. These findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating and require confirmation in larger, independently conducted RCTs with pharmacokinetic monitoring and clinical renal endpoints.

5.2. Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings from this preliminary trial suggest that theophylline may hold promise in modulating surrogate biomarkers of renal function and injury during vancomycin therapy. However, the clinical relevance of these biomarker changes is not established, as values remained within normal limits and no formal AKI endpoint was used. Further research with more robust designs, including standardized AKI definitions, pharmacokinetic monitoring, and clinical endpoints, is essential to confirm these results and definitively assess its clinical applicability.