1. Background

Kidney stone disease (urolithiasis) is a prevalent global disorder, and percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) remains the gold-standard treatment for large or complex stones due to its high efficacy and minimally invasive profile (1-3). While major urological guidelines firmly endorse PCNL, they also underscore its non-trivial risk profile, which includes hemorrhage, sepsis, and visceral injury (4-9) A critical, and often under-appreciated, aspect of mitigating these risks lies in the surgical planning of the percutaneous access point.

The decision to access a hydronephrotic versus a non-hydronephrotic calyx is a fundamental surgical choice, yet the evidence guiding this decision is conflicting and insufficient. On one hand, accessing a hydronephrotic calyx may be technically advantageous due to the dilated system, but this very dilation is often associated with parenchymal thinning and a theoretically higher risk of significant bleeding (4, 10-12). Conversely, puncturing a non-hydronephrotic system, while potentially preserving thicker parenchyma, is technically demanding and may increase the risk of complications like collecting system perforation or tract loss (4, 9-13). This presents a core surgical dilemma: the choice of access calyx carries a double-edged sword, where the technical ease of one approach may be counterbalanced by its unique set of risks.

Despite the profound implications of this choice, the current literature fails to provide a definitive consensus. While numerous studies have extensively cataloged the influence of stone-related factors and patient comorbidities on PCNL outcomes (9-12), the specific impact of the accessed calyx's status has been relegated to a secondary consideration. Previous work has described the anatomical changes but has not systematically analyzed how they directly influence critical postoperative outcomes. This constitutes a significant gap in clinical knowledge, as the pre-existing state of the kidney — specifically the presence or absence of hydronephrosis — induces pathophysiological changes that could directly dictate surgical success and patient recovery (14, 15).

2. Objectives

In order to move beyond descriptive anatomy and provide evidence-based guidance for surgical planning, this study aims to systematically compare postoperative outcomes and complication rates in patients undergoing PCNL, with a specific focus on the impact of accessing hydronephrotic versus non-hydronephrotic calyces.

3. Methods

3.1. Study Design and Setting

This retrospective analytical study was conducted at Imam Reza Medical Center, a tertiary referral hospital, which provides care for a diverse patient population with urolithiasis of varying complexity. Patients who underwent PCNL were categorized into two groups based on the status of the calyceal system accessed during the procedure: Group 1 (Hydronephrotic Calyces) and Group 2 (Non-hydronephrotic Calyces). Hydronephrosis was preoperatively identified and confirmed using imaging studies — either ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) — based on the presence of significant dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces.

3.2. Patient Population and Sampling

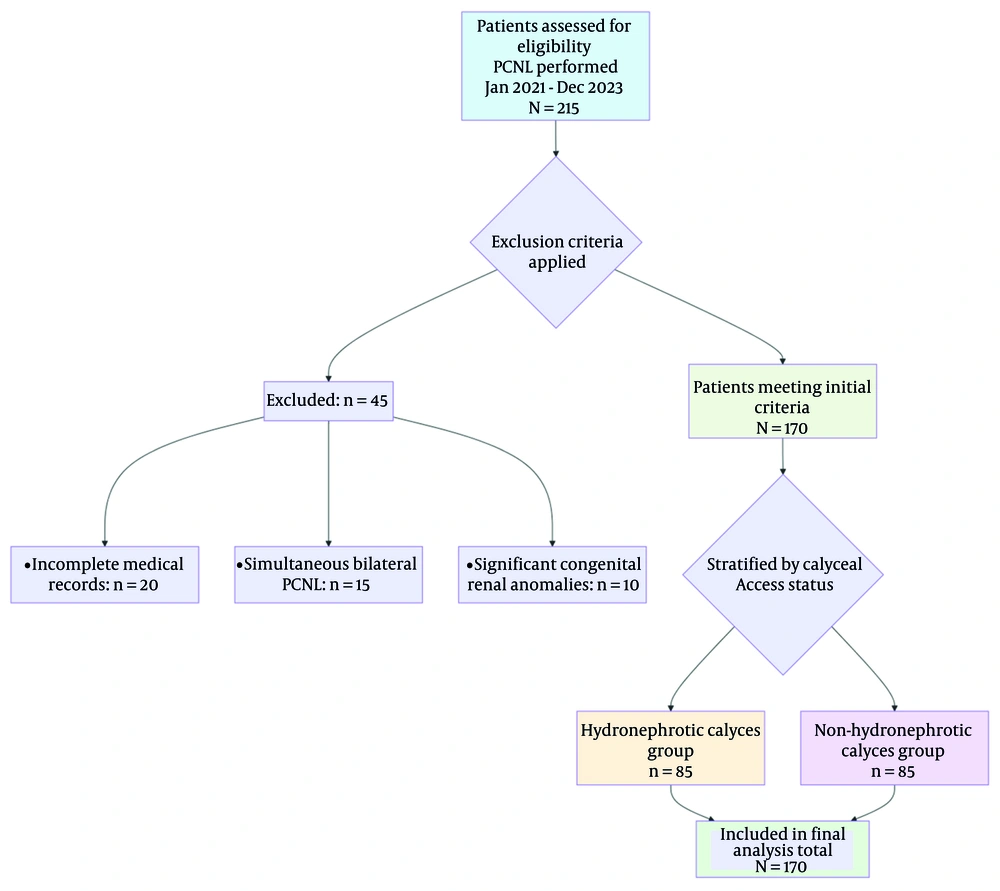

The study included all adult patients (≥ 18 years) who underwent PCNL between January 2021 and December 2023 at our institution. Exclusion criteria encompassed patients with incomplete medical records, those who underwent simultaneous bilateral procedures, or those with significant congenital renal anomalies that precluded standard PCNL access. A random sampling method was employed to ensure a representative cohort. A power analysis determined that a minimum sample size of 85 patients per group was required to achieve adequate statistical power, resulting in a total of 170 patients being included in the final analysis.

3.3. Surgical Technique

All PCNL procedures were performed by a team of experienced endourologists under general anesthesia. Patients were placed in the lithotomy position for cystoscopy and ureteral catheter placement, followed by repositioning to the prone position for percutaneous access. Renal puncture was performed under combined ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance. The tract was subsequently dilated using serial Amplatz dilators to accommodate either a 28 Fr or 30 Fr Amplatz sheath (Standard PCNL). Stone fragmentation was achieved using a combined ultrasonic and pneumatic lithotripter (Swiss LithoClast Master). The primary surgical strategy involved single-tract access; however, additional tracts were created at the surgeon's discretion for complex stone configurations. A nephrostomy tube was placed at the conclusion of the procedure.

Hydronephrosis was preoperatively identified on imaging studies (ultrasound or non-contrast CT). For the purpose of this study, a 'hydronephrotic calyx' was defined as one belonging to a renal unit with a renal pelvic anteroposterior diameter (APD) of ≥ 10 mm, a standard threshold for significant hydronephrosis in adults. Calyces in systems with an APD of < 10 mm were classified as non-hydronephrotic. The distribution of stones within hydronephrotic and non-hydronephrotic calyces (as defined above) was recorded.

3.4. Data Collection

Data were systematically extracted from electronic medical records and covered the following domains:

-Demographic Data: Age, sex.

-Clinical Characteristics: Body mass Index (BMI) and comorbidities [e.g., diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic kidney disease (CKD), liver disease].

-Stone Characteristics: Stone burden (size and volume) and anatomical location (e.g., renal pelvis, upper pole, lower pole).

-Intraoperative Data: Total operative time, access-related complications, number of percutaneous tracts (single vs. multiple), and sheath size.

Postoperative Outcomes:

-Hemoglobin Drop: The absolute difference between preoperative and the first postoperative hemoglobin levels (g/dL).

-Hospital Stay: The duration from the day of surgery to discharge (in days).

-Stone-free rate (SFR): Assessed at the 1-month follow-up and defined as the absence of residual fragments > 2 mm, corresponding to the standard definition of "Clinically Insignificant Residual Fragments" (CIRFs). Postoperative imaging was performed using non-contrast CT for patients with a high clinical suspicion of residual fragments or complications, or a kidneys-ureters-bladder (KUB) X-ray for routine follow-up. The 2 mm threshold was selected based on its established use in urological literature to define fragments that are unlikely to grow or cause clinical symptoms.

-Sepsis: Diagnosed according to established clinical criteria, including signs of systemic infection, supportive laboratory findings (e.g., leukocytosis, positive blood cultures), and the requirement for antibiotic therapy.

-Blood Transfusion: The need for packed red blood cell transfusion during the perioperative period (intraoperative or within 24 hours postoperatively).

-Creatinine Elevation: Defined as a postoperative increase in serum creatinine of > 0.3 mg/dL or a > 50% increase from the preoperative baseline.

-Fever: A documented body temperature ≥ 38.0°C occurring within the first 48 hours after surgery.

-Secondary Procedures: Any additional surgical or medical interventions required for residual stones or to manage complications.

-The CKD Progression: Defined as a sustained decline in renal function observed during the follow-up period. Progression was specifically defined as an increase in CKD stage (e.g., from Stage 2 to Stage 3a or higher) based on the KDIGO (kidney disease: Improving global outcomes) classification system. This assessment used the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), calculated from serum creatinine using the CKD-EPI formula. Serum creatinine levels for this long-term outcome were collected at the preoperative baseline and at the 3-month and 12-month postoperative follow-up visits. The minimum follow-up duration for inclusion in the CKD progression analysis was 12 months.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (16). Due to the retrospective and anonymized nature of the data analysis, the requirement for obtaining individual patient consent was waived by the approving Ethics Committee.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR) based on their distribution, and categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages (%).

Initial univariate comparisons between the two study groups (Hydronephrotic vs. Non-hydronephrotic Calyces) were performed using independent samples t-tests for normally distributed continuous data, Mann-Whitney U tests for non-normally distributed data, and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, as appropriate.

To account for potential confounding, multivariate analyses were conducted for primary outcomes. The selection of confounders for adjustment was based on clinical relevance and previously published literature, and included: Age, BMI, history of ipsilateral renal surgery, total stone volume, Guy’s stone score, and sheath size.

For continuous outcomes (hemoglobin drop, operative time, and hospital stay), multiple linear regression models were built to calculate adjusted effect estimates (β coefficients) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). For binary outcomes (stone clearance, sepsis, blood transfusion, fever, creatinine elevation, and need for secondary procedures), multivariate logistic regression models were built to calculate adjusted Odds Ratios (aORs) with 95% CI. To account for confounding variables, a multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to assess the independent association between calyceal access type and CKD progression. The model adjusted for age, BMI, stone volume, surgical history, and baseline CKD status.

Model fit was assessed using appropriate methods (e.g., Hosmer-Lemeshow test for logistic regression, and examination of residuals for linear regression). A two-sided P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

The study cohort selection process is shown in Figure 1. A total of 170 patients were included in the final analysis, evenly distributed with 85 patients in the hydronephrotic calyces group and 85 in the non-hydronephrotic calyces group. The baseline characteristics of both cohorts were well-matched, as detailed in Table 1. The mean age was nearly identical between groups (47.95 ± 13.00 years in the hydronephrotic group vs. 48.75 ± 12.00 years in the non-hydronephrotic group; P = 0.48). The cohort was predominantly male, with no significant difference in gender distribution between the hydronephrotic (61.6%) and non-hydronephrotic (58.8%) groups (P = 0.65). The vast majority of patients in both groups were married (91.9% vs. 97.5%, P = 0.18).

| Variables | Hydronephrotic Calyces Group | Non-hydronephrotic Calyces Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (y) | 47.95 ± 13.00 | 48.75 ± 12.00 | 0.48 |

| Male | 52 (61.6) | 50 (58.8) | 0.65 |

| Married | 78 (91.9) | 83 (97.5) | 0.18 |

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

4.2. Comorbidities

An analysis of patient comorbidities revealed one significant baseline difference between the groups, as summarized in Table 2.

| Comorbidity | Hydronephrotic Group | Non-hydronephrotic Group | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CKD | 15 (17.6) | 7 (8.2) | 0.03 |

| Liver Disease | 0 (0) | 4 (4.7) | 0.12 |

| DM | 18 (21.2) | 17 (20.0) | 0.84 |

| HTN | 26 (30.6) | 22 (25.9) | 0.44 |

Abbreviations: CKD, Chronic Kidney Disease; DM, Diabetes Mellitus; HTN, Hypertension.

a Values are expressed as No. (%).

Baseline CKD Prevalence: At the time of surgery, CKD was more than twice as prevalent in the hydronephrotic group, affecting 15 patients (17.6%), compared to only 7 patients (8.2%) in the non-hydronephrotic group, a difference that was statistically significant (P = 0.03).

Chronic kidney disease Progression Analysis: Given the significant difference in baseline CKD prevalence between the groups, a multivariable logistic regression was performed. After adjustment for age, BMI, stone volume, surgical history, and baseline CKD status, access through a hydronephrotic calyx remained independently associated with a significantly higher odds of CKD progression [adjusted Odds Ratio (aOR) = 4.1, 95% CI: 1.4 – 11.8, P = 0.009]. Liver disease was documented in 4 patients (4.7%) exclusively within the non-hydronephrotic group, though this finding was not statistically significant (P = 0.12). Other common comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus (P = 0.84) and hypertension (P = 0.44), were similarly distributed between the two groups with no significant differences.

4.3. Postoperative Outcomes

The primary postoperative outcomes and complications are detailed in Table 3. The mean hemoglobin drop was 2.1 ± 1.5 g/dL in the hydronephrotic group compared to 2.3 ± 1.7 g/dL in the non-hydronephrotic group, with a mean difference of -0.2 g/dL (95% CI: -0.7 to 0.3; P = 0.35). Correspondingly, the rates of blood transfusion were not significantly different. The mean hospital stay was also comparable, at 4.5 ± 2.1 days for the hydronephrotic group and 4.7 ± 2.3 days for the non-hydronephrotic group (P = 0.41).

| Outcome | Hydronephrotic Group | Non-hydronephrotic Group | P-Value | Effect Size (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous outcomes | ||||

| Hemoglobin drop (g/dL) | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 2.3 ± 1.7 | 0.35 | -0.2 (-0.7 to 0.3) c |

| Hospital stay (d) | 4.5 ± 2.1 | 4.7 ± 2.3 | 0.41 | -0.2 (-0.8 to 0.4) c |

| Binary outcomes | ||||

| Stone-free rate | 79 (92.8) | 80 (93.6) | 0.78 | 1.10 (0.40 to 3.02) d |

| Sepsis | 8 (9.4) | 10 (12.0) | 0.45 | 0.85 (0.36 to 2.01) d |

| Fever | 31 (36.5) | 27 (31.8) | 0.38 | 1.18 (0.81 to 1.73) d |

| Blood transfusion | 5 (5.9) | 7 (8.2) | 0.54 | 0.72 (0.24 to 2.16) d |

| Creatinine elevation | 9 (10.6) | 11 (12.9) | 0.72 | 0.84 (0.38 to 1.88) d |

| CKD progression | 19 (22.4) | 5 (5.9) | < 0.001 | 3.81 (1.51 to 9.62) d |

Abbreviation: CKD, Chronic Kidney Disease.

a Values are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± SD.

b The relative risk for stone-free status is for the outcome of not being stone-free to maintain a consistent interpretation where RR > 1 indicates higher risk in the hydronephrotic group.

c MD, mean difference (units: mL/min/1.73m² for eGFR; mm for APD).

d RR, relative risk (unitless).

In terms of efficacy and infective complications, the procedure was highly successful in both cohorts. The SFR was 92.8 in the hydronephrotic group and 93.6 in the non-hydronephrotic group (P = 0.78). The relative risk (RR) for not being stone-free was 1.10 (95 CI: 0.40 to 3.02). The incidence of postoperative sepsis was low and similar between groups (9.4 vs. 12.0, P = 0.45). Postoperative fever was the most common complication, occurring in 36.5 of the hydronephrotic group and 31.8 of the non-hydronephrotic group, a difference that was not statistically significant (P = 0.38).

The most notable finding was in long-term renal function. While acute perioperative creatinine elevation showed no significant difference (P = 0.72), the hydronephrotic group exhibited a statistically significant higher incidence of CKD progression during follow-up (P < 0.001). The rate of blood transfusion was comparable between groups (5.9 vs. 8.2, P = 0.54).

4.4. Relative Risk Analysis

The RR and odds ratio (OR) analysis corroborated the findings from the direct comparisons. This formal analysis confirmed that the only outcome for which the hydronephrotic group had a significantly elevated risk was the progression of CKD. For all other perioperative complications — including bleeding, infection, and fever — the calculated risks were statistically comparable between the two groups.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the impact of calyceal hydrostatic status on outcomes following PCNL. The principal finding is that accessing a hydronephrotic calyx was independently associated with a significantly higher risk of long-term (12-month) follow-up CKD progression, despite demonstrating equivalent safety and efficacy in all perioperative metrics, including SFRs, bleeding, and infective complications. Even after controlling for the significant difference in baseline renal function and other potential confounders through multivariable analysis, access through a hydronephrotic calyx was identified as an independent predictor for CKD progression, with patients having over four times the adjusted odds of functional decline.

The equivalence in perioperative outcomes between the two groups underscores the robustness of modern PCNL. The fact that factors such as operative time, hemoglobin drop, and SFR were comparable suggests that, with contemporary imaging and surgical expertise, accessing a dilated calyx does not present a greater technical challenge or immediate risk (17, 18). This aligns with a growing body of evidence indicating that procedural success is more strongly influenced by surgeon experience and integrated surgical protocols than by specific anatomical variations like hydronephrosis (4, 9). The high SFRs achieved in both cohorts further reinforce that the presence of hydronephrosis should not deter surgeons from selecting the most direct and efficient calyceal access for achieving complete stone-free status.

A particularly insightful finding was the lack of an increased bleeding risk in the hydronephrotic group. This contradicts the conventional surgical intuition that a thinned, dilated parenchyma might be more vulnerable to vascular injury. Our results, supported by multivariate analysis controlling for tract size and stone burden, suggest that the determinants of bleeding are multifactorial and may be more related to endophytic stone location, polar arterial anatomy, and the precision of puncture rather than the degree of calyceal dilation itself (19, 20). This finding is reassuring and indicates that the fear of increased hemorrhage should not be a primary factor in avoiding a hydronephrotic calyx if it is the optimal access point.

The most critical finding of this study is the strong and independent association between hydronephrotic access and CKD progression. This is unlikely to be a consequence of the surgical act itself, but rather a reflection of the underlying renal pathology. A hydronephrotic calyx is often the end-result of chronic obstruction, which leads to irreversible parenchymal damage through mechanisms such as tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and apoptotic loss of nephrons (15, 21, 22). Therefore, we posit that the hydronephrotic calyx serves as a macroscopic marker of a kidney that has already suffered a significant loss of its functional reserve. In such kidneys, even the well-controlled ischemic and inflammatory stress of a PCNL procedure may be sufficient to unmask this latent vulnerability and tip the scale towards measurable CKD progression (23-25). This hypothesis is further supported by the higher baseline prevalence of chronic kidney disease CKD in our hydronephrotic group, indicating a pre-existing susceptibility.

The primary clinical implication of our study is that the identification of a hydronephrotic calyx on preoperative imaging should trigger a more comprehensive renal functional assessment and a dedicated long-term follow-up plan. While PCNL remains the definitive treatment for removing the obstruction, it does not reverse the chronic damage already inflicted upon the renal parenchyma. Surgeons should manage these patients with the understanding that they are treating a pathologically distinct kidney with reduced functional reserve. Preoperative counseling should accordingly address not only the high likelihood of procedural success but also the importance of ongoing renal surveillance postoperatively. This is especially relevant in light of evolving technological advancements that improve perioperative safety but do not eliminate the renal vulnerability associated with chronic obstruction-related damage (17-20, 26).

These findings align with contemporary evidence demonstrating that improvements in imaging technology, tract dilation systems, and endoscopic instruments have standardized PCNL outcomes across diverse renal anatomies (17, 18, 26). Recent studies on robot-assisted and 3D imaging guidance further show that enhanced procedural precision minimizes anatomical variability as a risk factor (17, 18). Contemporary comparative studies of traditional versus mini-percutaneous nephrolithotomy similarly report that tract size, stone burden, and patient comorbidities — not hydronephrosis — are the dominant determinants of bleeding risk (19, 20). Recent literature emphasizes that even with advances such as robotic platforms, enhanced 3D visualization, and improved endoscopic technology, long-term renal outcomes depend primarily on the patient’s baseline renal health rather than technical aspects of the procedure (17, 18, 26).

5.1. Limitations

The interpretations of this study must be considered in the context of its inherent limitations. Firstly, the retrospective and single-center design introduces a potential for selection bias, as the choice of calyceal access was at the surgeon's discretion and may have been influenced by unmeasured patient or stone characteristics. Secondly, despite our efforts to use predefined criteria, measurement bias cannot be ruled out due to the non-blinded nature of data collection from medical records.

A significant limitation was the initial lack of a standardized, quantitative grading system for hydronephrosis. Although we have applied a post-hoc definition (APD ≥ 10 mm) to ensure group consistency for this analysis, the lack of a prospectively applied grading system, such as the Society for Fetal Urology (SFU) classification, is a limitation. Furthermore, the retrospective design precluded the standardized grading of postoperative complications using a system like Clavien-Dindo, as the granular data on intervention specifics required for accurate grading was not consistently available, limiting direct comparison with studies that use standardized complication grading systems (e.g., Clavien-Dindo).

In addition, our evaluation of long-term renal function, while demonstrating a significant association, was limited to serum creatinine and eGFR. We lacked more sensitive measures such as measured glomerular filtration rate (mGFR), urinary biomarkers (e.g., proteinuria), or functional renal imaging (e.g., DMSA scan), which could provide a more nuanced understanding of the renal functional changes. Finally, as with any observational study, the presence of unmeasured confounding factors (e.g., subtle variations in surgical technique, patient adherence to follow-up) may persist despite multivariate adjustment.

5.2. Future Directions

Future research should aim for prospective, randomized designs that standardize access strategies and patient follow-up. Incorporating more sensitive measures of renal function, such as mGFR or functional imaging, could provide deeper insights into the subtleties of renal functional changes. Multicenter collaborations would be invaluable for achieving the sample size necessary to power investigations into rarer complications and to solidify the generalizability of these findings.

5.3. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that PCNL access through a hydronephrotic calyx is a safe and effective procedure, with perioperative outcomes comparable to those achieved with non-hydronephrotic access. The most significant finding is that access through a hydronephrotic calyx was identified as a strong and independent predictor for the progression of CKD, even after controlling for baseline renal function.

This finding suggests that a hydronephrotic calyx is more than a simple anatomical variant; it is a clinically significant marker of a kidney with diminished functional reserve and heightened vulnerability to functional decline. Therefore, its identification on preoperative imaging should prompt a comprehensive renal risk assessment, meticulous surgical planning, and mandatory long-term functional follow-up. Ultimately, while surgical expertise ensures procedural success, recognizing the prognostic implications of a hydronephrotic system is crucial for optimizing long-term renal outcomes in these patients.