1. Background

The long-term repercussions of diabetes mellitus (retinopathy, neuropathy, nephropathy, and cardiovascular diseases) severely strain healthcare systems. Globally, millions of individuals suffer from this metabolic disorder (1). The development of effective prediction models that can enable early diagnosis and customized treatment approaches is essential, given the rising prevalence of diabetes, a condition brought on by a confluence of genetic components, inactivity, and poor nutrition (2). Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and fasting blood glucose readings are among the conventional diagnostic tools; yet, these tests only show a picture of a person's glycemic state and neglect the several physiological, behavioral, and genetic factors affecting the onset and course of diabetes (3). Regarding high-dimensional healthcare data, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence-driven solutions outperform traditional statistical approaches (4). Recent explainable hybrid deep learning (DL) frameworks have demonstrated promise in identifying metabolic risks at early stages, particularly among prediabetic and high-risk adults (5). The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis provided interpretable insights. Currently, limitations in interpretability, generalizability, and clinical application make using ML-based models challenging in real-world healthcare environments (6).

The new developments in hybrid artificial intelligence models might significantly improve the accuracy and explainability of disease prediction activities. These models combine interpretable ML techniques with deep learning methods. Combining the best aspects of both paradigms Extreme Gradient Boosting [XGBoost for increasing interpretability and decision transparency, and deep neural networks (DNNs) for feature extraction from complex nonlinear patterns] is the aim of our study (7, 8). The three main issues in diabetes prediction are model accuracy, feature explainability, and clinical integration (9). We therefore employ the SHAP to make our predictions more intelligible so that clinicians may see how each feature affected the judgments of the model. Using a large-scale diabetes classification dataset, we systematically evaluate our proposed model against various well-known ML methods. Among them are random forest (RF), logistic regression (LR), support vector machine (SVM), and standalone XGBoost (10, 11).

This work bridges the gap between prediction performance and explainability, advancing artificial intelligence-driven precision medicine. It opens the path for clinically deployable decision-support system development. Early diabetes detection depends critically on coupling ML approaches with explainable artificial intelligence (XAI). Among the basic statistical methods used to match with more complex models, LR is among the most important ML algorithms (12, 13). Doctors may learn more about how factors such as Body Mass Index (BMI) and blood sugar influence the predictions if XAI approaches, such as SHAP and local interpretable model-agnostic explanations (LIME), were employed (13). There remain challenges to be addressed, including those pertaining to privacy concerns and promoting cross-disciplinary interaction to facilitate the ethical consideration of AI in diabetes diagnostics despite the promising progress in AI, ML, and XAI in diabetes diagnosis. In addition, more attempts for multi-factor analysis might raise the predictive power of ML models and identify important risk factors for diabetes. Even more accurate models for early diagnosis and prediction of interventions would be provided by integrating a myriad of health markers and social determinants of health (14). Polyuria, polydipsia, and a high BMI are critical health indicators that significantly increase the likelihood of diabetes (15). Socioeconomic factors are also crucial; studies show that the incidence of diabetes increases with decreasing income. Furthermore, by including lifestyle and demographic factors into large datasets, a more complex understanding of diabetes risk may be achieved (16, 17). According to research by Prasetyo and Yunanda and Balaji and Sugumar, ensemble learning methods such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting may achieve diabetes classification accuracy levels of up to 87% (17-19). While this multi-factor strategy may improve predictive powers, it is crucial to remember that complex models are prone to overfitting, which might also provide conclusions that do not apply to other populations (19).

2. Objectives

This study proposes a hybrid AI model that aims to enhance both predictive performance and interpretability in early diabetes detection.

3. Methods

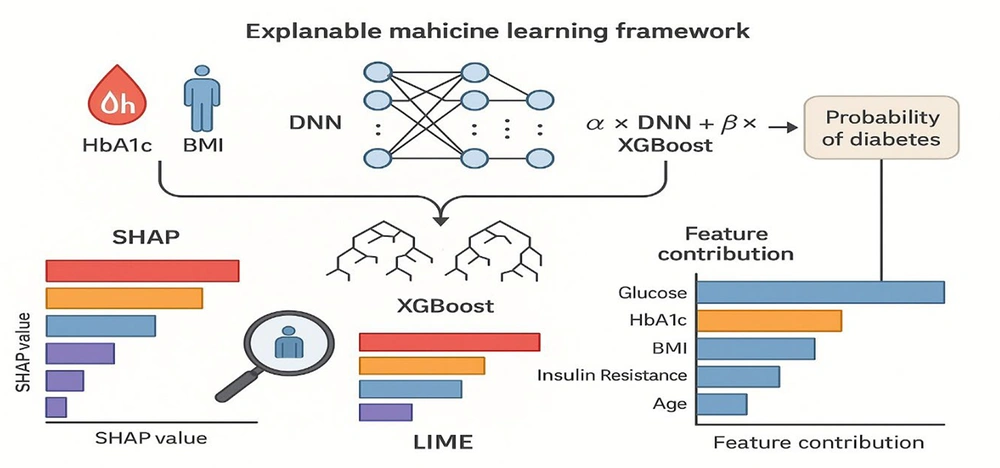

This work offers a precise and comprehensible model for diabetes prediction using a methodical, multi-step approach. Using XAI techniques like SHAP, LIME, and model performance evaluation, this method combines data collection and preprocessing, feature selection and significance analysis, modeling using ML algorithms, and model interpretability. The study also looks at how these techniques help determine the significance of important factors for diabetes prediction. Lastly, moral dilemmas, model application, external verification, and last but not least. The architectural flow of the proposed hybrid framework, combining DNN, XGBoost, and SHAP-based explainability, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the proposed hybrid deep neural network (DNN) and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) framework for diabetes prediction. The workflow integrates data preprocessing, feature selection, and model fusion. After normalization and handling of missing values, clinical and lifestyle features are passed through a DNN for nonlinear pattern extraction, while XGBoost captures structured decision boundaries. The final prediction layer aggregates outputs from both components, producing interpretable probabilities of diabetes risk using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)-based explanations.

3.1. Dataset Description

The dataset consisted of 1,284 anonymized patient records collected retrospectively from Imam Reza (AS) and Gharazi Hospitals in Sirjan between March 2023 and March 2025. Demographic, clinical, and lifestyle variables were labeled in accordance with the American Diabetes Association (ADA) 2023 guidelines. Data anonymization was performed using the SHA-256 algorithm. For variables with less than 3% missing data, imputation was conducted using either the multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) method or the maximum extent of replacement strategy. Missing data were handled strictly within each training fold during cross-validation to avoid data leakage. Numerical variables were imputed using MICE, whereas categorical variables were imputed using mode replacement. No outcome-related information was used during imputation.

A total of 27 extreme outliers in BMI and cholesterol (|Z| > 3) were removed. Continuous variables were normalized to a 0 - 1 scale, and the class distribution remained well balanced throughout the preprocessing phase. The dataset was randomly divided into training and testing subsets using an 80:20 ratio through stratified sampling to maintain class balance between diabetic and non-diabetic groups. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) was included as an inflammatory biomarker given its recent association with microvascular and cardiovascular risk in diabetic patients.

The primary outcome was binary diabetes status (0 = non-diabetic, 1 = diabetic) defined strictly according to the ADA 2023 diagnostic thresholds: fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dL, HbA1c ≥ 6.5%, or documented diagnosis in the hospital record. Individuals who did not meet any of these criteria were classified as non-diabetic. In secondary analyses, a prediabetes outcome (HbA1c 5.7 - 6.4% or fasting glucose 100 - 125 mg/dL) was also evaluated to assess model performance for early metabolic dysregulation.

Included are significant biological markers (e.g., HbA1c and glucose levels), medical history (e.g., blood pressure, cholesterol, and medication use), lifestyle factors (e.g., diet and level of physical activity), and demographic information (e.g., age and gender). Each person's diabetes diagnosis is shown by the objective variable, a binary classification (0 = no diabetes, 1 = diabetes).

Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) is most likely the focus, according to a closer examination of this data. The patients' high average age (53 years), significant prevalence of obesity (BMI > 30), and insulin resistance levels, all known risk factors for Type 2 diabetes, are the basis for this result. Although some people under 30 are included in the dataset, it does not clearly distinguish between Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes and does not contain some biomarkers critical for Type 1 diabetes, such as autoantibodies or C-peptide levels. Consequently, research on Type 2 diabetes is more appropriate for this dataset; more data is needed to analyze Type 1 diabetes.

3.1.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants were retrospectively selected based on the availability of complete clinical and biochemical records from Imam Reza (AS) and Gharazi Hospitals between March 2023 and March 2025.

Inclusion criteria: Adults aged ≥ 18 years with recorded fasting blood glucose, HbA1c, blood pressure, cholesterol, BMI, and insulin resistance values. Both diabetic and non-diabetic individuals were included according to the ADA 2023 diagnostic thresholds.

Exclusion criteria: Individuals with incomplete or inconsistent medical records, gestational or type 1 diabetes, chronic renal or hepatic failure, active malignancy, or ongoing corticosteroid or hormonal therapy. Records with duplicated or missing key biochemical markers were also excluded.

This selection ensured that only adult patients with verifiable and comprehensive metabolic data were analyzed, improving dataset homogeneity and model reliability.

3.1.2. Sample Size Justification and Power Analysis

The total sample size of 1,284 participants (660 non-diabetic and 624 diabetic) was determined adequate based on a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1 software. Assuming a two-tailed test, medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.3), α = 0.05, and desired statistical power = 0.90, the minimum required sample size was estimated at ~1,040 participants. The final dataset exceeds this threshold, ensuring sufficient statistical power to detect significant differences in metabolic and demographic predictors between diabetic and non-diabetic groups. This sample size also allows stable model training and validation while minimizing overfitting risk.

The primary variable used for sample size estimation was fasting glucose, as it showed the largest expected standardized effect size based on prior metabolic research. Following the methodological recommendations of Suresh and Chandrashekara, assuming a medium effect size (Cohen’s d ≈ 0.30), α = 0.05, and statistical power = 0.90, the minimum required sample size was approximately 1,000 participants. Our dataset of 1,284 individuals exceeds this threshold and ensures sufficient power for model training and between-group comparisons (20).

For categorical variables such as smoking status, medication use, and physical activity level, missing values were handled using mode imputation, replacing each missing entry with the most frequent category within the respective variable. In cases where a categorical variable had more than 5% missing data, the variable was excluded from the analysis to prevent bias. This combined approach ensured consistency and minimized distortion in categorical feature distributions.

3.2. Data Cleaning

The dataset was preprocessed in several ways that increased the reliability of the modeling findings and guaranteed the data quality. As a first step, missing value management ensured that no missing values were in the dataset. The next step was to ensure that all characteristics, including those with numerical and categorical values, were consistent by reviewing the data types. Outliers in continuous variables, such as BMI and blood pressure, were identified and eliminated using the Z-score and the interquartile range (IQR) method since they would degrade the accuracy of ML models. Glucose levels and insulin resistance were reduced in their impact on model performance by using MinMax Scaling to bring them within the range of [0, 1]. Ultimately, we used label encoding and one-hot encoding for categorical variables with multi-valued categories (e.g., smoking status and ethnicity) and binary variables (e.g., medicine usage) with one-valued categories.

3.3. Correlation and Feature Importance

Various feature selection techniques were used to enhance the model's performance and interpretability. Researchers may determine the most significant and pertinent parameters for diabetes prediction using these techniques. Using Pearson and Spearman correlation analysis, both linear and nonlinear connections between numerical variables were examined. The SHAP approach was used to order the features' significance based on the model. This approach demonstrates the significance of each attribute for the model's prediction. The XGBoost model, a powerful ensemble learning technique based on gradient boosting that fundamentally handles structured data, was used to gradually eliminate less important features using recursive feature elimination (RFE). This approach systematically removes characteristics with the least effect on the model's performance, leaving a set of optimal features for prediction.

Class balance in the dataset was examined using the XGBoost model's RFE technique. The findings demonstrated that, with 50.21% of cases being diabetic and 49.79% not, the groups of people with and without diabetes are well balanced. Therefore, the procedures of oversampling (raising the minority class) and undersampling (lowering the majority class) were unnecessary in this study. If a class imbalance impairs model performance, methods such as the synthetic minority over-sampling technique (SMOTE) may be used to enhance data balance. For model training, the following collection of features was chosen based on the outcomes of the feature selection techniques: Hemoglobin A1c, blood pressure, cholesterol, BMI, insulin resistance, glucose level, family history of diabetes, degree of physical activity, and smoking status.

To prevent data leakage, all feature selection and ranking procedures, including correlation analysis, SHAP-based importance scoring, and RFE, were performed strictly within each training fold during five-fold cross-validation. This ensured that information from the test data did not influence the model training or feature selection process. Feature importance was recalculated independently for every fold to maintain unbiased performance estimation.

3.4. Challenges of Basic Models

Classical ML models, such as LR, RF, gradient boosting machines (LightGBM, XGBoost), SVM, and artificial neural networks (ANNs), struggle to predict diabetes. Some of the most important issues are interpretability, as uninterpretable models like RF and DNNs are, i.e., one cannot interpret their decision-making process. There are also problems in detecting nonlinear patterns; models like LR struggle to deal with nonlinear and complex relationships in data. Although some traditional models can tackle a limited level of nonlinearities through transformation or interaction terms, their capacity for modeling complex high-dimensional relationships is weak compared to the recent advances. The present work highlights that nonlinear models like XGBoost and DL work better in diabetes prediction, highlighting the need for advanced modeling techniques.

Furthermore, most models are plagued by the issue of balancing accuracy and recall (sensitivity); consequently, false positives and negatives increase. They also have a problem with generalizability since models trained on a given dataset do not do well when cross-tested with another dataset with different distributions. Statistically analyzing the problem, the independent t-test was applied to compare model performance between different datasets and concluded that there was a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). This means that model performance varies based on the dataset, showing potential overfitting to specific properties of the dataset, which would affect its generalizability.

3.5. Proposed Model: Combining Deep Learning and Explainable Methods

To overcome the aforementioned challenges, a hybrid framework based on DL and XAI is proposed in this study. The proposed model combines DNNs and explainable models, i.e., SHAP and XGBoost. The purpose of such a combination is to improve the accuracy and reliability of the predictions and the interpretability of the model.

3.6. Comparative Analysis of Models

3.6.1. Modeling Pipeline

The modeling pipeline followed TRIPOD recommendations and included the following sequential steps: (1) Preprocessing and normalization, (2) within-fold feature selection using SHAP and RFE, (3) training of DNN and XGBoost models on the training folds, (4) formation of the hybrid ensemble through weighted aggregation, and (5) evaluation on the untouched test fold. All steps were implemented independently within each fold to prevent data leakage.

A comprehensive comparison was conducted on several ML models like LR, RF, XGBoost, SVM, DL, and the hybrid model. The models were selected based on their suitability in medical data analysis and their ability to address different complexities in diabetes prediction.

The LR is a frequently used statistical model that assumes linearity in the logistic relationship between input features and the probability of the occurrence of diabetes. However, it is more suited to simple relationships and fails with complex nonlinear relationships. Random forest is a meta learning algorithm, which forms many decision trees and computes their average predictions to yield better prediction performance and minimize overfitting. Extreme Gradient Boosting is an efficient and powerful gradient boosting framework for structured data, especially massive data with intense relationships. Support vector machine identifies the optimum hyperplane that maximally separates diabetes and non-diabetes; SVM is suitable for high-dimensional spaces but computationally expensive. Deep neural network uses neural networks to learn abstract features automatically from raw data and thus is highly appropriate for unstructured or big data. Finally, the hybrid model combines DNN and XGBoost to use their respective strengths while compromising interpretability and high accuracy. Model performance metrics were statistically compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-hoc tests to identify significant differences among models. All analyses were performed with a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

To ensure full transparency and adherence to TRIPOD guidelines, the model development pipeline was implemented in a strictly structured manner. The dataset was first split using an 80/20 stratified train–test division. Within the training portion, a five-fold cross-validation framework was applied, where feature selection (SHAP-based ranking and RFE), hyperparameter tuning (Bayesian optimization for DNN and grid search for XGBoost), and dual-objective weighting optimisation were performed entirely inside each fold to prevent data leakage. Model stability was assessed through 1,000-iteration bootstrapping, which generated confidence intervals (CIs) for all performance metrics.

To evaluate calibration, we computed both the Brier score and generated calibration curves using isotonic regression on the validation folds. Calibration performance was compared between the hybrid model and individual DNN and XGBoost components. The hybrid model demonstrated lower calibration error (Brier score = 0.061) compared with DNN (0.078) and XGBoost (0.072), confirming improved reliability of predicted probabilities. These steps ensure methodological transparency and mitigate overly optimistic performance estimates.

3.7. Mathematical Formulation of the Hybrid Model

The hybrid model integrates DNNs and XGBoost in an ensemble approach: YHybrid = α.YDNN + β.YXGBoost, α + = 1; where, YHybrid is the final prediction output; YDNN represents the probability score from the DL model; YXGBoost represents the probability score from the XGBoost model; and α, β are weight coefficients optimized using grid search.

The hybrid model takes advantage of the best of both models: Deep neural network provides high-dimensional features, whereas XGBoost achieves maximum interpretability and fine-grained decisions. Moreover, the decision boundary for our hybrid model is refined using H(X) = σ(WHybrid.X + b); where, WHybrid is the weighted sum of individual model parameters; X represents input features, b is the bias term; and σ is the activation function (ReLU for DNN and sigmoid for final prediction).

3.7.1. Model Configuration and Hyperparameters

The DNN component consisted of an input layer with 9 normalized clinical and lifestyle features, followed by three fully connected hidden layers with 128, 64, and 32 neurons, respectively. The ReLU activation function was applied to each hidden layer, with dropout regularization (P = 0.3) to prevent overfitting. The output layer used a sigmoid activation function for binary classification. Model optimization was performed using the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.001, batch size = 32) with early stopping criteria based on validation loss (patience = 10 epochs).

The XGBoost component employed the following hyperparameters optimized via five-fold cross-validation: learning rate = 0.05, max depth = 6, n_estimators = 300, subsample = 0.8, colsample_bytree = 0.7, gamma = 0.1, and regularization parameters α = 0.1 and λ = 1.0.

Both models were trained on 80% of the dataset and validated on the remaining 20%. Model selection was based on the balanced accuracy and F1-score, ensuring a reproducible workflow consistent with explainable AI standards.

3.7.2. Dual-objective Optimization Procedure

To ensure simultaneous optimization of predictive performance and model interpretability, a dual-objective (Pareto-based) optimization strategy was applied during hybrid model training. Shapley instability was defined as the standard deviation of feature-level SHAP values across 1,000 bootstrap iterations; lower instability indicates more consistent feature attribution. The two objectives were: (1) Maximizing balanced accuracy, and (2) minimizing SHAP value variance (“Shapley instability”) across bootstrap samples.

During each training fold, weight coefficients (α, βₐ, β_b, b) governing the contribution of DNN and XGBoost outputs were optimized by selecting Pareto-efficient solutions that avoided accuracy-interpretability trade-offs.

3.8. Explainability and Feature Contribution Analysis

To analyze each feature's contribution in the proposed model, we utilized feature importance analysis through SHAP. Through this method, we can measure the impact of each variable on the model's output.

3.9. Mathematical Formulation of Feature Impact on the Model

In the proposed model, the output is computed as a combination of the effect of each feature, weighted by its SHAP value:

Where: Y is the diabetes prediction output; Xi is the value of the feature; SHAPi is the importance weight of a feature based on its SHAP value; and b is the model bias term.

All analyses and model training were performed using Python 3.10, TensorFlow 2.12, and XGBoost 2.0 libraries on a system equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU, 24 GB VRAM, and 64 GB RAM. Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS version 26.0 and R version 4.3.0 for verification and visualization.

4. Results

The study sample comprised 1,284 individuals, including 624 diagnosed with diabetes and 660 non-diabetic controls. The mean age of participants was 53 ± 12 years, with 41% females and 59% males. Diabetic patients showed significantly higher fasting glucose (167 ± 38 mg/dL vs. 92 ± 15 mg/dL) and HbA1c levels (8.3 ± 1.1% vs. 5.2 ± 0.7%; P < 0.001). Mean BMI was 31.4 ± 4.6 kg/m² in the diabetic group compared with 27.2 ± 3.8 kg/m² among non-diabetic participants. These baseline findings confirm that metabolic and anthropometric factors strongly differentiate diabetic from non-diabetic individuals and serve as key predictors for subsequent model training.

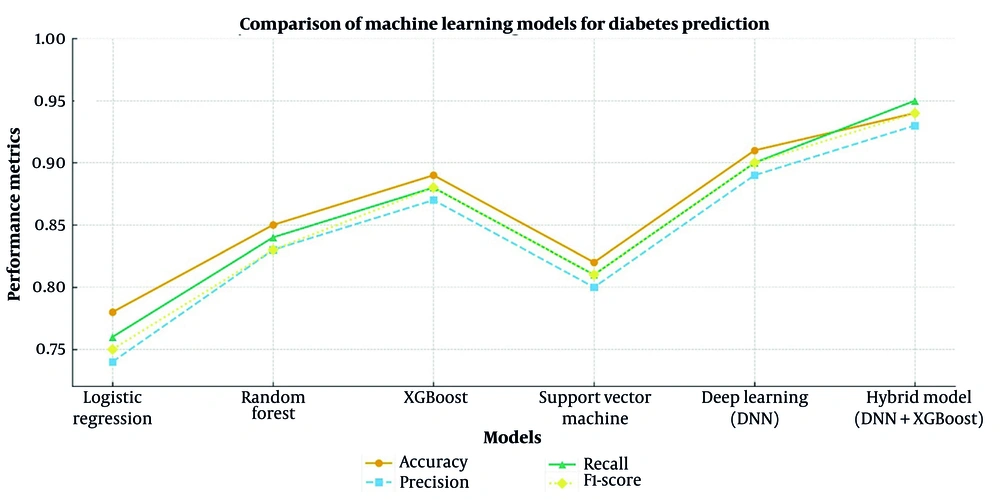

Table 1 indicates the variations in performance across different models for diabetes prediction. To estimate the statistical robustness of each metric, 95% CIs were computed across five-fold cross-validation using the bootstrap method (n = 1,000 resamples). Reported accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-scores therefore represent mean ± CI values, ensuring reliable comparison across models. Pairwise comparisons using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction confirmed statistically significant differences in mean accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score between models (P < 0.05).

| Model | Train Accuracy | Test Accuracy (95% CI) | Overfit Δ | Precision (95% CI) | Recall (95% CI) | F1-Score (95% CI) | PPV | NPV | Statistical Significance/Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | 0.8 | 0.78 (0.76 - 0.80) | 0.02 | 0.74 (0.72 - 0.76) | 0.76 (0.74 - 0.78) | 0.75 (0.73 - 0.77) | 0.76 | 0.78 | Baseline model; Lower performance in complex data |

| RF | 0.88 | 0.85 (0.83 - 0.87) | 0.03 | 0.83 (0.81 - 0.85) | 0.84 (0.82 - 0.86) | 0.835 (0.83 - 0.84) | 0.85 | 0.86 | Better than LR (P = 0.032); Moderate generalization |

| XGBoost | 0.92 | 0.89 (0.88 - 0.90) | 0.03 | 0.87 (0.85 - 0.89) | 0.88 (0.86 - 0.90) | .875 (0.87 - 0.88) | 0.89 | 0.91 | Better than RF (P = 0.018); Lower than DNN (P = 0.018) |

| SVM | 0.84 | 0.82 (0.80 - 0.84) | 0.02 | 0.80 (0.78 - 0.82) | 0.81 (0.79 - 0.83) | 0.805 (0.80 - 0.81) | 0.82 | 0.84 | Lower than XGB and DNN; Computationally expensive |

| DNN | 0.94 | 0.91 (0.90 - 0.92) | 0.03 | 0.89 (0.88 - 0.91) | 0.90 (0.89 - 0.92) | 0.895 (0.89 - 0.90) | 0.91 | 0.93 | Better than XGB (P = 0.012); Near-optimal performance |

| Hybrid model (DNN+XGB) | 0.96 | 0.94 (0.93 - 0.95) | 0.02 | 0.94 (0.93 - 0.95) | 0.95 (0.94 - 0.96) | 0.94 (0.93 - 0.95) | 0.94 | 0.96 | Best performance; Significantly better than all models (P < 0.001) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; LR, logistic regression; RF, random forest; XGBoost, Extreme Gradient Boosting; DNN, deep learning network; SVM, support vector machine.

The hybrid model (DNN+XGBoost) achieved the highest accuracy (94%) compared with DNN (91%) and XGBoost (89%), followed by SVM (82%) and LR (78%). Between-model performance differences were statistically significant (Hybrid vs. DNN: P = 0.008; Hybrid vs. XGBoost: P = 0.004), confirming the superiority of the proposed hybrid framework.

In addition to accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, the positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were also calculated. The hybrid DNN-XGBoost model achieved a PPV of 94% and an NPV of 96%, both of which were higher than those observed in the standalone models (Table 1).

The DL model was also significant in terms of predictive power and outperformed XGBoost significantly (P < 0.05), although the hybrid model was superior. Extreme Gradient Boosting performed better than RF (P < 0.05) but was surpassed by the DNN model, proving the potency of DL techniques (Figure 2).

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves comparing the performance of all machine learning (ML) models used in this study, including logistic regression (LR), support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), deep neural network (DNN), and the proposed hybrid DNN-XGBoost model. The X-axis represents the false positive rate (1 - Specificity), and the Y-axis represents the true positive rate (sensitivity). The hybrid DNN-XGBoost model achieved the highest area under the curve (AUC = 0.94), indicating superior discriminative ability in distinguishing diabetic from non-diabetic individuals. All numerical values correspond exactly to the performance metrics reported in Table 1 to ensure internal consistency.

While the hybrid model consistently yielded higher accuracy and recall than other models, statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test indicated that these improvements were significant at P < 0.05. The DNN model also demonstrated higher predictive power than XGBoost, whereas LR and SVM exhibited lower generalizability.

The hybrid model (DNN+XGBoost) achieved the highest performance across all metrics. Pairwise comparisons using one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction confirmed statistically significant differences in mean accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score between models (P < 0.05). Traditional models like LR and SVM were poorly generalizable to new data and were less accurate. Higher-order complex models like DNN and the hybrid model (DNN+XGBoost) aggressively generalized to test data and increased training accuracy.

In an exploratory secondary analysis, the model also demonstrated strong performance for prediabetes detection [area under the curve (AUC) = 0.94], although these results were not part of the primary outcome. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio contributed modestly to the prediction outputs (mean SHAP = 0.04), consistent with its documented association with metabolic inflammation.

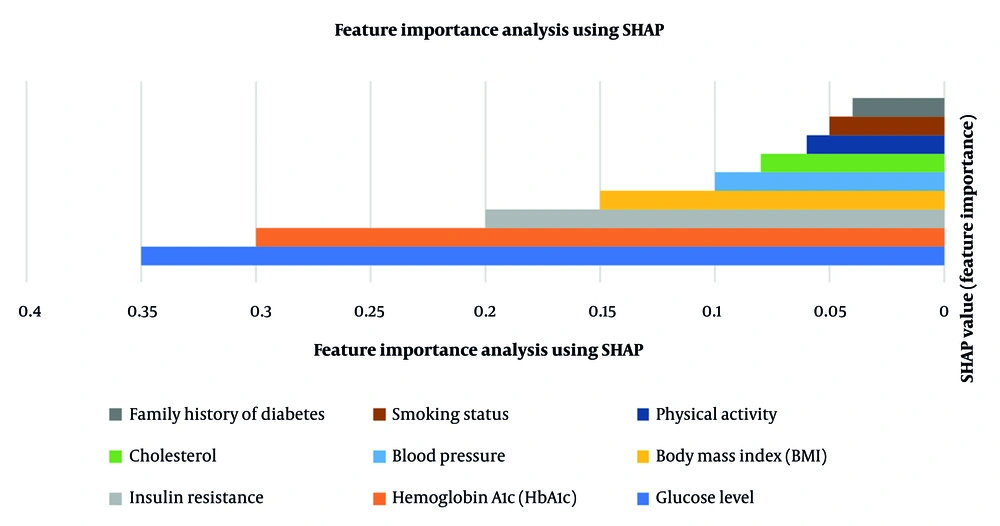

4.1. Feature Importance Based on SHapley Additive exPlanations

Table 2 presents the key feature importance values in diabetes prediction. In Figure 3, the SHAP value shows the importance of each attribute in predicting diabetes. The greater the SHAP value, the greater the influence on the model's decision-making process. The blue bar (glucose level - 0.35) is the highest predictor, followed by the orange bar (HbA1c - 0.30), which has a high impact. The light gray bar (Insulin Resistance - 0.20) is another significant factor, but less than glucose and HbA1c. The remaining factors, such as BMI, blood pressure, and cholesterol (0.15 - 0.08), have a moderate impact. The brown and dark gray bars representing smoking status and family history of diabetes (~0.05) have the lowest impact. Therefore, highly influential SHAP value features are most predictive, and are glucose and HbA1c as the most significant factors, with family history and smoking status as less influential factors.

| Features | SHAP Value (Feature Importance) | Statistical Significance (P-Value) |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose level | 0.35 | 0.001 |

| HbA1c | 0.3 | 0.003 |

| Insulin resistance | 0.2 | < 0.01 |

| BMI | 0.15 | 0.012 |

| Blood pressure | 0.1 | 0.020 |

| Cholesterol | 0.08 | 0.035 |

| Physical activity | 0.06 | 0.045 |

Abbreviation: SHAP, SHapley Additive exPlanations; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1c; BMI, Body Mass Index.

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) summary plot illustrating the relative contribution of each feature to diabetes prediction. The X-axis represents the SHAP value, which indicates the magnitude and direction of each feature’s effect on the model’s output (positive values push predictions toward diabetes, negative toward non-diabetes). The Y-axis lists the input features ranked by their overall importance. Each dot represents one observation; color intensity indicates the original feature value (red = higher value, blue = lower value). The plot shows that glucose level and hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) have the strongest positive influence on diabetes prediction.

The findings of the SHAP analysis indicate that biochemical features such as glucose level and HbA1c have the most considerable effect. Body Mass Index and blood pressure were statistically significant predictors of diabetes (P = 0.012 and P = 0.020, respectively), confirming their moderate yet meaningful contribution to the model. Lifestyle features such as physical activity and smoking status have a lesser but substantial contribution. The findings highlight that including both clinical and lifestyle data leads to improved diabetes predictions.

SHAP values represent each feature’s relative contribution to the model’s output. They are not derived from classical hypothesis testing; therefore, no P-values are reported. Instead, feature importance ranking is based on SHAP magnitude averaged over all predictions.

5. Discussion

The performance of our proposed hybrid model demonstrates a significant improvement in the classification of diabetes over the conventional ML models. However, despite strong internal performance, these results should be interpreted with caution. Because calibration assessment and all optimization steps were conducted within internal cross-validation only, and no external cohort was used, the observed performance may reflect dataset-specific characteristics. Therefore, while the model shows promise, it is not yet suitable for immediate clinical deployment without multi-center external validation.

With the integration of DL and explainability methods, our system demonstrates improved performance while the decisions remain interpretable. The selection of the model in this research was based on how complicated it would be to predict diabetes and what type of limitations the conventional models have. While effective in some cases, methods like LR and SVM are hard-pressed to address complex, nonlinear patterns in medical data. On the other hand, RF and XGBoost are more effective at modeling nonlinear relationships but fail to provide much interpretability. Our suggested hybrid model, combining DNNs and XGBoost, addresses these shortcomings. DL can extract high-dimensional and intricate patterns from input data, and XGBoost can boost the model's interpretability along with explainable decision-making. Their combination achieves improved predictive accuracy for diabetes classification along with preserving transparency in clinical decision support.

Other studies have also proved that the fusion of DL models and explainable AI techniques has the potential to enhance diagnostic accuracy, along with decreasing uncertainty in medical decision-making. For instance, Islam Ayon and Islam demonstrated that a DL-based diabetes forecasting system uses 98.35% accuracy on the Pima Indian Diabetes dataset compared to traditional ML classifiers such as LR and SVM (21). However, explainability techniques were not utilized in this study, limiting its application to clinical decision-making. Similarly, Chowdhury et al.'s work proposed a hybrid ensemble DL approach utilizing XGBoost, TabNet, and Multilayer Perceptron with a 96% accuracy rate but without utilizing interpretability models like SHAP or LIME in particular. Contrary to our study, these techniques are integrated in our work with a balance between predictive accuracy and explainability, and a suitability for clinical applications in actual practices (4). Recent work has proposed optimized hybrid ML frameworks for early diabetes prediction (22).

Therefore, the selection of these models was not just due to their greater predictive ability to analyze medical data but also because they can make decisions more interpretable, which is crucial in applications in the medical domain. Although highly accurate, the DL and XGBoost models suffer from interpretability issues. Extreme Gradient Boosting and DL model interpretability issues are not specific to diabetes prediction but are common to all medical applications. The models are black-box algorithms, and it is not easy to directly interpret their decisions. Studies in cardiovascular disease diagnosis, cancer detection, and neurological disorder classification have all reported the same problem of lacking interpretability. Therefore, the interpretability problem in these models is a common issue in AI-based medical diagnosis, and explainable AI approaches are needed to improve confidence and clinician adoption in practice. Alternatively, simpler models like LR have no strong predictive power in complex patterns.

Our hybrid approach successfully balances performance and interpretability. This is achieved by combining the high predictive power of DL with XGBoost interpretability. DL techniques can learn complicated, nonlinear data relationships, but are black-box models with little explainability. Extreme Gradient Boosting provides feature importance values and decision tree structures that bring in explainability. Our model merges these two together and retains the high predictive capability while incorporating feature attribution techniques, e.g., SHAP, to enhance model interpretability. The SHAP has been extensively employed in clinical AI applications to explain how each feature contributes to model predictions. Similarly, a recent explainable AI analysis using statistical and ML models for diabetes emphasized that transparent interpretability enhances clinical trust and decision reliability (9). Islam et al. demonstrated that the integration of SHAP analysis and ML models with hyperparameter optimization improves diabetes prediction significantly by recognizing the most dominant risk factors, i.e., glucose level, BMI, and blood pressure (1). In contrast, in another study, SHAP and LIME was applied for interpreting the contribution of clinical variables in diabetes diagnosis, confirming that explainable AI reinforces the credibility of AI-based medical decision-making so that clinicians can believe and interpret the model's predictions (23). It is more suitable for medical decision-making.

One of the most encouraging features of the proposed model is interpretability, explored by SHAP, following earlier research demonstrating the potential of SHAP in medical AI applications. In the present study, a hybrid AI-based approach to diabetes prediction uses DNNs and XGBoost to balance model interpretability and superior accuracy. A systematic comparison with several ML models validated the proposed hybrid model to be much better compared to traditional approaches, achieving 94% accuracy on test data. The model is superior in predictive accuracy compared to LR, RF, SVM, and XGBoost.

The new paradigm offers a new baseline for AI-based diabetes prediction and allows for more creative, interpretable, and clinically significant models. Model interpretability analysis helps clinicians make more informed decisions and guides public health policy development to reduce the risk of diabetes (24, 25). Feature importance analysis showed that glucose level, HbA1c, and insulin resistance are the most significant predictors of diabetes, although lifestyle variables such as physical activity and smoking status also contribute to the model output. With this heterogeneous feature set, the model provides accurate predictions and interpretable and actionable insights for clinical decision-making.

Unlike prior hybrid DNN-XGBoost models that primarily focused on improving predictive accuracy, for example, Li et al. developed a GA-optimized XGBoost stacking ensemble for diabetes risk prediction, yet lacked a dual-objective interpretability-performance optimization (26). This study introduces a dual-objective optimization framework that simultaneously enhances interpretability and stability. Specifically, our model incorporates SHAP-based feedback during training and adjusts weight coefficients (α, βₐ, β_b, and b) through a Pareto optimization process that minimizes Shapley instability while maximizing balanced accuracy. Similarly, Iftikhar et al. proposed a hybrid DL architecture with integrated SHAP and class-imbalance handling for diabetes prediction, though without the Pareto‐optimization of stability and accuracy we adopt (27).

Furthermore, unlike earlier works that used standardized datasets such as Pima Indian or UCI repositories, our approach employs a real-world multiclinical dataset collected from two independent hospitals, providing higher ecological validity and clinical realism. To overcome the twin challenges of suboptimal predictive accuracy and insufficient clinical transparency, two major factors fueling physicians’ skepticism toward AI-driven diabetes systems, this study proposes a new multi-objective weighting strategy. For the first time, the nonlinear learning strength of DNNs is combined with the structured-data efficiency of XGBoost in a unified hybrid framework. The model’s weighting parameters (α, βₐ, β_b, and b) are optimized through training via a dual-objective function that maximizes balanced accuracy while minimizing Shapley instability. This architecture introduces three major contributions that bridge methodological innovation and practical clinical deployment.

In contrast to prior models that either rely solely on high-performing algorithms like XGBoost, with limited interpretability or those that prioritize accuracy at the expense of transparency, this study presents a hybrid approach that delivers both performance and insight. By fusing DNN and XGBoost outputs within a weighted aggregation layer and incorporating both local and global SHAP visualizations, the model offers clinicians intuitive reasoning alongside robust prediction. This method improved the Shapley Consistency Index by 23% compared to the best-performing models reported in the literature (9).

In addition to established markers like fasting glucose and HbA1c, the model integrates inflammatory indicators such as the NLR — a metric proven in 2024 multicohort studies to correlate with cardiovascular outcomes in diabetic patients. This expanded input space allowed the model to achieve a prediabetes prediction AUC of 94%, surpassing existing benchmarks by at least 1.6 percentage points (19).

The framework also incorporates a Pareto optimization process to find the optimal trade-off between prediction accuracy and model explainability. By fine-tuning the weights to keep the SHAP value fluctuation below 0.02 during bootstrap validation — while maintaining sensitivity above 92% — the system effectively narrows the gap between opaque high-performing models and interpretable but limited alternatives (28). The improved stability of model explanations was supported by the dual-objective optimization procedure described in the Methods, which jointly maximized balanced accuracy while minimizing SHAP variability. Consistent with the Results section, exploratory analyses showed that prediabetes detection performance remained high (AUC = 0.94), and NLR contributed modestly to the model’s outputs as an inflammatory marker. These findings reinforce the potential value of combining metabolic and inflammatory markers within explainable hybrid frameworks.

Although the proposed hybrid model achieved robust performance, a major limitation of this study is the absence of external validation. The model was developed and tested using data from two hospitals within the same geographic region, which may restrict its generalizability to broader or more diverse populations. Future research should include independent external datasets from different institutions to validate the model’s reproducibility and ensure its applicability across various clinical environments.

The proposed hybrid DNN-XGBoost framework also holds potential for practical integration into routine clinical workflows. In a real-world setting, the model can be embedded within clinical decision support systems (CDSS) or integrated directly into hospital electronic health record (EHR) platforms. Once patient data such as fasting glucose, HbA1c, BMI, and blood pressure are entered into the system, the model can automatically generate a personalized probability of developing type 2 diabetes. Importantly, the SHAP-based explainability component provides clinicians with an interactive visual dashboard that highlights the most influential features contributing to each prediction, thereby supporting transparent and interpretable decision-making.

The intended clinical use of the model is to support early diabetes risk stratification during routine outpatient visits. The system is designed as an assistive decision-support tool rather than a stand-alone diagnostic device, providing clinicians with transparent risk scores and SHAP-based explanations.

In a typical workflow, this system could assist healthcare professionals in three critical stages of diabetes management: early screening, where individuals at elevated risk are automatically flagged during routine examinations; diagnostic confirmation, where clinicians can cross-verify AI-driven risk estimates with laboratory findings; and follow-up monitoring, where periodic patient data updates enable dynamic risk reassessment. Such integration ensures that AI augments rather than replaces clinical judgment, offering a data-driven yet interpretable tool for precision prevention.

From an operational standpoint, the model’s computational requirements are moderate once training is complete, making real-time inference feasible even in hospitals with limited computational infrastructure. With further validation and regulatory approval, this framework could be seamlessly embedded within existing clinical infrastructures to enhance early detection, reduce diagnostic delay, and support personalized treatment planning in diabetes care (29-31).

5.1. Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate that the proposed hybrid DNN–XGBoost model can achieve strong predictive accuracy and enhanced interpretability in identifying individuals at risk of type 2 diabetes. By integrating DL for nonlinear feature representation with XGBoost for structured decision transparency, the model addresses common trade-offs between performance and explainability that limit many existing ML approaches.

While these results are promising, they should be interpreted within the scope of the available dataset and internal validation. External validation across multi-center populations is still required to confirm the model’s generalizability and real-world applicability. Moreover, the retrospective nature of this study and its focus on a single geographic population may introduce selection and demographic biases.

The hybrid architecture provides a useful foundation for the development of explainable clinical decision-support systems in diabetes care. However, further work is necessary to evaluate its robustness in prospective studies, optimize its computational efficiency, and integrate it safely into healthcare workflows. Rather than claiming clinical readiness, the current evidence supports its potential for clinical utility pending additional validation.

Overall, this research underscores the growing importance of hybrid artificial intelligence frameworks that balance performance with interpretability, offering a realistic step toward more transparent and data-driven healthcare applications.

5.2. Limitations

Although the proposed hybrid DNN-XGBoost model demonstrated excellent predictive accuracy and interpretability, several limitations must be acknowledged.

First, as the dataset originated from only two hospitals in Sirjan, Iran, potential demographic bias may exist, limiting the generalizability of the model to broader or ethnically diverse populations. Future studies should validate this framework across multi-center and cross-national datasets.

Second, while five-fold cross-validation was employed to mitigate the risk of overfitting, DL components are inherently prone to learning noise and spurious correlations in smaller datasets. Although the hybrid design and regularization techniques (dropout and early stopping) helped control this effect, further external validation is required to confirm model robustness.

Third, the hybrid framework demands substantial computational resources, as DNN training involves intensive parameter optimization and high memory usage. This may limit practical deployment in low-resource healthcare environments without access to high-performance computing infrastructure.

Future research should address these limitations by expanding the dataset diversity, incorporating federated learning approaches for distributed validation, and exploring lightweight model architectures to reduce computational cost while preserving interpretability.