1. Context

Accurate dose calculation is a cornerstone of modern radiotherapy, directly influencing tumor control and normal tissue sparing (1). Conventional algorithms such as Monte Carlo (MC), pencil beam convolution, and the analytical anisotropic algorithm (AAA) have long served as clinical standards. However, these methods often struggle with complex anatomical heterogeneities, dynamic organ motion, and computational inefficiencies in adaptive workflows (2-5).

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) have introduced transformative possibilities for dose prediction, treatment planning, and quality assurance (6). The AI encompasses a broad spectrum of algorithmic families — including machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), reinforcement learning (RL), Bayesian models, fuzzy logic systems, and evolutionary algorithms — each offering unique strengths in modeling nonlinear relationships, learning from large datasets, and generalizing across patient populations (7).

In radiotherapy, AI applications have expanded from image segmentation and contouring to dose estimation, plan optimization, and toxicity prediction. Particularly, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), transformer-based architectures, and hybrid ensemble models have demonstrated promising results in predicting three-dimensional (3D) dose distributions with high spatial fidelity. The RL has shown potential in adaptive planning scenarios, while Bayesian and fuzzy logic models offer enhanced interpretability and uncertainty quantification (8-12), (13-15).

Despite these advances, several challenges hinder clinical translation. Many AI models lack external validation, suffer from limited generalizability, and are often trained on institution-specific datasets (11). Moreover, explainability remains a critical barrier, especially in high-stakes clinical decisions where transparency and accountability are essential (16). Regulatory frameworks for AI in medicine are still evolving, and integration with existing treatment planning systems (TPS) requires robust interoperability and human-AI collaboration protocols (17).

2. Objectives

This review aims to critically evaluate the current landscape of AI-based dose calculation methods in radiotherapy. We categorize and compare six major algorithmic families — ML, DL, RL, Bayesian, fuzzy, and evolutionary — based on their dosimetric accuracy, computational efficiency, interpretability, and clinical applicability. By synthesizing findings from over 160 peer-reviewed studies, we highlight key trends, limitations, and future directions for AI integration in radiotherapy workflows.

Ultimately, this work seeks to bridge the gap between algorithmic innovation and clinical implementation, offering a structured roadmap for researchers, physicists, and oncologists navigating the evolving intersection of AI and radiation oncology.

3. Methods

This review was conducted through a structured and comprehensive evaluation of the literature on AI applications in radiotherapy dose calculation. A multi-step methodology was employed to ensure scientific rigor and relevance.

3.1. Literature Search

Databases including PubMed, Scopus, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar were queried for studies published up to August 3, 2025. Search terms included combinations of “radiotherapy dose calculation”, “AI in radiotherapy”, “machine learning”, “deep learning”, “Bayesian networks”, “fuzzy logic”, and “treatment planning optimization”. Boolean operators were used to refine results and capture a broad spectrum of traditional and AI-based approaches.

3.2. Criteria

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Studies were selected if they (1) focused on radiotherapy dose calculation or treatment planning, (2) applied AI techniques such as ML, DL, RL, Bayesian, fuzzy, or evolutionary algorithms, (3) discussed clinical applications, challenges, or future directions, and (4) were published in peer-reviewed journals or reliable scientific repositories.

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

Articles were excluded if they (1) were not in English, (2) lacked methodological detail, (3) focused solely on non-radiotherapy AI applications, or (4) were opinion pieces without any underlying data.

3.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Full-text reviews were conducted to assess alignment with the review’s objectives. Extracted data included algorithm types, dosimetric performance, clinical integration, and reported limitations. Studies were categorized into six AI domains: The ML, DL, RL, Bayesian, fuzzy logic, and evolutionary algorithms.

3.4. Synthesis Strategy

Findings were synthesized into thematic sections: Traditional dose calculation methods, AI roles, algorithmic techniques, challenges, clinical applications, and future directions. Emphasis was placed on comparative performance, interpretability, and clinical feasibility. Citations were retained to ensure traceability and academic integrity.

3.5. Scope and Coverage

A total of 160 references were included, spanning experimental studies, technical reports, and systematic reviews. The selected literature reflects diverse cancer types, imaging modalities, and TPS, offering a panoramic view of AI’s evolving role in radiotherapy.

4. Results

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Models

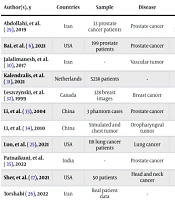

The AI models for radiotherapy dose calculation span six major algorithmic families, each offering distinct advantages in terms of dosimetric accuracy, computational efficiency, and clinical feasibility. Below is a comparative synthesis of these approaches and Table 1 summarizes this section. In Table 1, performance metrics are synthesized from studies (18-23), (24-28) and reflect general trends across cancer types and imaging modalities. Table 2 also shows a summary of key studies on the applications of AI in radiotherapy dose calculation and treatment planning.

| Algorithm Types | Accuracy | Interpretability | Clinical Integration | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML (RF, SVM) | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| DL (CNN, transformer) | High | Low | Emerging | High |

| RL (DQN) | High | Low | Limited | Very high |

| Bayesian/fuzzy | Moderate | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Evolutionary | High | Moderate | Experimental | High |

Abbreviations: ML, machine learning; RF, Random Forest; SVM, Support Vector Machines; DL, deep learning; CNN, convolutional neural network; RL, reinforcement learning; DQN, Deep Q-Networks.

| Author(s), y | Countries | Sample | Disease | Algorithm | Evaluation Method | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdollahi, et al. (29), 2019 | Iran | 33 prostate cancer patients | Prostate cancer | LSVM, LREG, BENB, SGD, KNN, DT, RF, ADBO, GANB | Tenfold cross-validation | Post-T2 models predictive (AUC: 0.632); GS prediction higher with T2 (AUC: 0.739) vs. ADC (AUC: 0.70). |

| Bai, et al. (6), 2021 | USA | 199 prostate patients | Prostate cancer | Lightweight CNN | Time | Denoiser runs in 39 ms vs. 454 ms, 11.6x faster; completes MC dose in ~0.15 s. |

| Jalalimanesh, et al. (30), 2017 | Iran | - | Vascular tumor | Distributed Q-learning | Simulation | Robust solutions for treatment plans under varying conditions. |

| Kalendralis, et al. (31), 2021 | Netherlands | 5238 patients | - | Bayesian network | AUC | AUC: 67.8% overall; 90.4% for table angle errors, 54.5% for PTV errors. |

| Leszczynski, et al. (32), 1999 | Canada | 328 breast images | Breast cancer | Fuzzy k-NN | Correlation | High agreement with expert (correlation 0.89). |

| Li, et al. (33), 2004 | China | 3 phantom cases | Prostate cancer | GA, CG | Time | Optimal angles found in < 5 min (cases A, B), 13 - 36 min (case C, spine, prostate). |

| Li and Lei (34), 2010 | China | Simulated and chest tumor | Oropharyngeal tumor | GA | Iterations | DNA-GA optimized in 20 iterations vs. 45 for GA; improved OAR sparing. |

| Luo, et al. (25), 2021 | USA | 118 lung cancer patients | Lung cancer | SA-BN, EK-NBN | AU-FROC | SA-BN improved prediction (AU-FROC: 0.83) vs. EK-NBN (0.70). |

| Patnaikuni, et al. (35), 2022 | India | - | Prostate cancer | Two-level fuzzy logic | Qualitative assessment | Acceptable rectal risk estimation without compromising tumor coverage. |

| Sher, et al. (17), 2021 | USA | 50 patients | Head and neck cancer | Decision tree | Dose reduction | Hybrid directive reduced OAR doses by 4.3-16 Gy vs. physician directive. |

| Torshabi (26), 2022 | Iran | Real patient data | - | Fuzzy logic, NN | Setup error reduction | Setup error reduced from 1.47 mm to 0.4432 mm. |

| Valdes, et al. (36), 2017 | USA | 17 patients | Lung and head-neck | Statistical similarity | Efficiency | Enabled efficient identification of achievable prior plans. |

| Wu C, et al. (37), 2021 | USA | 290 patients | Multiple sites | DL | Gamma passing rate | Gamma passing rate (1 mm/1%) improved to 89.7 - 99.6% across sites. |

| Wu and Zhu (28), 2001 | USA | 3 cases | Brain and abdominal | GA | Dose conformity | NGA reduced max dose (102.6 - 104.6%) vs. manual (105.4 - 106.3%). |

| Xing, et al. (38), 2020 | USA | 120 lung cancer patients | Lung cancer | Hierarchically dense U-Net | Gamma passing rate | Boosted AAA dose improved gamma passing rate to 97.6% vs. 87.8%. |

Abbreviations: LREG, Logistic Regression; KNN, K-Nearest Neighbors; RF, Random Forest; CNN, convolutional neural network; MC, Monte Carlo; GA, genetic algorithms; OAT, organ-at-risk; SA-BN, situational awareness Bayesian networks; DL, deep learning; NGA, novel genetic algorithms; AAA, analytical anisotropic algorithm; ADBO, AdaBoost; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient; AU-FROC, area under free-response ROC curve; BENB, Bayesian ensemble naive bayes; CG, conjugate gradient; DT, decision tree; EK-NBN, expert knowledge-naive Bayesian network; GANB, gaussian naive bayes; GS, Gleason score; LSVM, linear support vector machine; NN, neural network; PTV, planning target volume; SGD, stochastic gradient descent.

4.1.1. Machine Learning Models

The ML techniques such as Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Logistic Regression (LREG), and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) have been widely applied to dose prediction and plan classification tasks. The RF and SVM models demonstrated robust performance in identifying organ-at-risk (OAR) dose thresholds and predicting toxicity outcomes (35-37). However, their reliance on handcrafted features and limited scalability to 3D dose maps restrict broader clinical adoption (18, 19).

4.1.2. Deep Learning Architectures

The CNNs, U-Net variants, and transformer-based models have shown superior performance in voxel-level dose prediction. The CNNs trained on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) datasets achieved high spatial fidelity in head and neck, prostate, and lung cancer cases. Transformer models further improved contextual learning and generalization across institutions. Despite their accuracy, DL models often lack interpretability and require large annotated datasets for training (20-23).

4.1.3. Reinforcement Learning Applications

The RL algorithms, particularly Deep Q-Networks (DQN), have been explored for adaptive planning and beam angle optimization. These models dynamically learn optimal dose delivery strategies based on reward functions tied to tumor coverage and OAR sparing. While promising, RL approaches remain computationally intensive and are rarely integrated into commercial TPS (24).

4.1.4. Bayesian and Fuzzy Logic Systems

Bayesian networks [e.g., Bayesian ensemble naive bayes (BENB), expert knowledge-naive Bayesian network (EK-NBN)] and fuzzy logic models offer enhanced transparency and uncertainty quantification. These systems are particularly useful in scenarios with incomplete data or ambiguous clinical inputs. Situational awareness Bayesian networks (SA-BN) have been applied to decision support in dose escalation protocols. Although interpretable, these models often underperform in high-dimensional imaging contexts (25, 26).

4.1.5. Evolutionary Algorithms

Genetic algorithms (GA), particle swarm optimization (PSO), and novel genetic algorithms (NGA) have been employed for multi-objective dose optimization. These methods excel in exploring large solution spaces and balancing trade-offs between tumor coverage and normal tissue sparing. However, they require extensive computational resources and are sensitive to parameter tuning (27, 28).

5. Discussion

5.1. Challenges and Strategic Considerations

While AI has demonstrated remarkable potential in radiotherapy dose calculation, its clinical integration remains constrained by several technical, ethical, and operational challenges. This section synthesizes key limitations and proposes strategic considerations for future implementation. A summary of key studies on AI applications in radiotherapy dose calculation and treatment planning is shown in Table 3.

| Challenges | Strategic Response |

|---|---|

| Limited data diversity | Federated learning, multi-center data sharing |

| Lack of interpretability | Explainable AI, uncertainty modeling |

| Regulatory ambiguity | Joint guidelines from clinical and regulatory bodies |

| Poor clinical validation | Prospective trials, hybrid human-AI workflows |

| Algorithmic bias | Bias detection, fairness-aware training |

| Workflow disruption | Modular integration with existing TPS |

| Human-machine collaboration | Clinician training, collaborative interface design |

Abbreviations: AI, artificial intelligence; TPS, treatment planning systems.

5.1.1. Data Quality and Generalizability

The AI models require large, diverse, and high-quality datasets for training and validation. However, radiotherapy datasets often suffer from institutional bias, limited sample sizes, and inconsistent annotation standards (39-41). These limitations hinder model generalizability across patient populations, tumor types, and imaging modalities. Multi-institutional data sharing frameworks and federated learning approaches may help mitigate these issues while preserving patient privacy.

5.1.2. Interpretability and Trust

The DL models, particularly convolutional and transformer-based architectures, are often criticized for their “black-box” nature (42-44). Clinicians may hesitate to adopt AI-driven dose recommendations without clear explanations of algorithmic reasoning. Incorporating explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques — such as attention maps, feature attribution, and uncertainty quantification — can enhance transparency and foster clinical trust.

5.1.3. Regulatory and Ethical Barriers

The regulatory landscape for AI in medicine is still evolving. Most jurisdictions lack standardized protocols for validating and approving AI-based dose calculation tools (45, 46). Ethical concerns also arise regarding data ownership, informed consent, and accountability for treatment outcomes. Collaborative efforts between developers, clinicians, and regulatory bodies are essential to establish robust guidelines and ethical safeguards.

5.1.4. Clinical Validation and Workflow Integration

Despite promising results in silico, few AI models have undergone rigorous clinical validation or prospective trials (7, 47). Integration into existing TPS requires seamless interoperability, user-friendly interfaces, and minimal disruption to clinical workflows. Hybrid models that combine AI predictions with human oversight may offer a pragmatic pathway toward adoption.

5.1.5. Algorithmic Bias and Robustness

The AI models trained on imbalanced datasets may inadvertently propagate biases related to age, gender, ethnicity, or tumor subtype (47-49). Such biases can lead to inequitable treatment recommendations and compromise patient safety. Strategies such as bias auditing, fairness metrics, and inclusive dataset curation are critical to ensure equitable AI deployment.

5.1.6. Human-Machine Collaboration

The AI should augment — not replace — clinical expertise. Effective human-machine interaction requires training clinicians to interpret algorithmic outputs, recognize limitations, and make informed decisions (7, 50, 51). Decision support systems must be designed to facilitate collaboration, not automation, preserving the clinician’s role as the final arbiter of care.

By addressing these challenges through interdisciplinary collaboration, transparent development, and rigorous validation, AI technologies can be safely and effectively integrated into radiotherapy dose calculation. The path forward lies not only in algorithmic innovation but in thoughtful system design that respects clinical realities and ethical imperatives.

5.1.7. Conclusions

The AI has emerged as a transformative force in radiotherapy dose calculation, offering unprecedented capabilities in precision, adaptability, and computational efficiency. By leveraging diverse algorithmic families — including ML, DL, RL, Bayesian models, fuzzy logic, and evolutionary techniques — AI enables personalized treatment planning, real-time dose optimization, and enhanced clinical decision support.

This review synthesized findings from over 160 peer-reviewed studies, highlighting the comparative performance of AI models across cancer types and treatment modalities. The DL architectures demonstrated superior spatial accuracy, while Bayesian and fuzzy systems offered interpretability and uncertainty modeling. The RL and evolutionary algorithms showed promise in adaptive and multi-objective planning, albeit with significant computational demands.

Despite these advancements, several limitations persist. Most AI models are trained on institution-specific datasets, limiting their generalizability. The lack of external validation and standardized benchmarking impedes clinical trust and regulatory approval. Furthermore, the “black-box” nature of many algorithms raises concerns about transparency and accountability in high-stakes clinical environments. Ethical challenges — including data privacy, algorithmic bias, and human-machine interaction — must also be addressed to ensure equitable and safe deployment.

To bridge the gap between innovation and implementation, future research should prioritize:

- Multi-institutional data sharing and federated learning frameworks.

- Development of XAI tools for clinical interpretability.

- Prospective clinical trials and real-world validation studies.

- Integration of AI into existing TPS with modular design.

- Training programs for clinicians to foster effective human-AI collaboration.

In conclusion, AI-driven dose calculation represents a paradigm shift in radiation oncology. While the path to clinical integration is complex, the potential benefits — improved accuracy, efficiency, and personalization — are substantial. By addressing current limitations through interdisciplinary collaboration and ethical innovation, AI can redefine the future of radiotherapy and contribute meaningfully to precision cancer care.