1. Background

Congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) are a large class of rare inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) in which glycosylation of a variety of tissue proteins and/or lipids is deficient. They are also recognized as carbohydrate-deficient glycoprotein syndromes (CDG syndromes). CDG can cause often severe and sometimes fatal dysfunctions of several different organ systems, particularly the nervous system, muscles, and intestines in affected infants (1). Jaeken et al. first described CDG in 1980 (2). These disorders are classified according to the incorrect glycosylation of biomolecules, including proteins, lipids, or glycosylphosphatidylinositol. Therefore, subdivisions of CDG are as follows: (A) Disorders related to protein N-glycosylation (type I and II), (B) Disorders associated with protein O-glycosylation, (C) Disorders pertaining to glycosphingolipid and GPI-anchor glycosylation, and (D) Disorders affecting multiple glycosylation and other pathways.

Protein glycosylation occurs in two main ways: N-glycosylation involves the assembly of glycans in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and their subsequent attachment to the nitrogen (N-) group of asparagine residues, while O-glycosylation involves the attachment of sugars to the hydroxyl (O-) groups of serine or threonine. Disorders of N-glycosylation are widely recognized as the most prevalent types of CDG. These can be categorized into two subtypes: (A) defects of oligosaccharide assembly and transfer, and (B) defects in oligosaccharide trimming and processing that occur after they are bound to proteins (3). Over 160 various types of CDG have been discovered so far (1).

Recently, Jaeken et al. developed a classification pattern for naming types of CDG. This pattern involves using the official abbreviation of the abnormal gene followed by a dash and CDG to name each type of CDG (4, 5), such as PMM2-CDG, which is formally known as CDG-Ia, the most common subtype of CDG, in which the PMM2 gene defect causes loss of phosphomannomutase 2 (PMM2) enzyme that is responsible for the conversion of mannose-6-phosphate into mannose-1-phosphate (6). The majority of CDG exhibit autosomal recessive inheritance patterns and are known for their wide-ranging multisystem impact. This can include developmental disabilities, hypotonia with involvement of multiple organ systems, as well as symptoms such as hypoglycemia and protein-losing enteropathy (7, 8).

CDG are attributed to a deficiency or absence of specific enzymes or proteins crucial for synthesizing glycans, as well as their interactions with other proteins or lipids during glycosylation. The process of glycosylation is extensive and intricate, involving the modification of numerous proteins. This process engages hundreds of distinct genes and specific enzymes (3). Typical symptoms may indicate recognition of a CDG, a comprehensive patient history, and a thorough clinical assessment. Several specialized tests may be required to confirm a CDG diagnosis and identify the specific subtype. Due to the wide-ranging clinical manifestations observed in CDG patients, it is advised to thoroughly explore and eliminate any unexplained syndromes that involve multiple bodily systems (9). Exome sequencing (ES) is rapidly becoming an early test of an individual’s DNA when physicians suspect a genetic abnormality (3).

In the current study, two patients with multiple organ dysfunctions belonging to an Iranian consanguineous family were identified as PMM2-CDG. The study identified a pathogenic variant in the Sistan and Balouchestan province of Iran (Balouch ethnicity). It is essential to recognize pathogenic variants across various ethnicities to ensure effective genetic counseling for affected families.

2. Methods

2.1. Family Recruitment and DNA Extraction

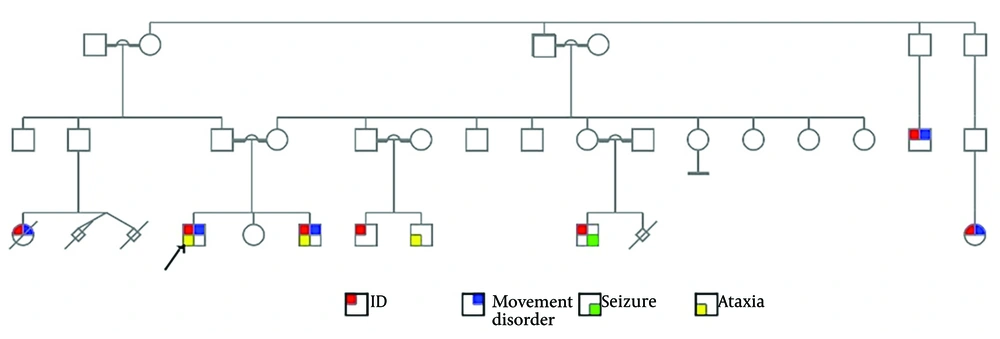

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (IR.MUI.MED.REC.1400.042). Two siblings exhibiting severe intellectual disabilities were identified from a consanguineous family residing in the Sistan and Balouchestan province of Iran, belonging to the Balouch ethnic group. Genetic counseling was provided, and family pedigrees were constructed utilizing the Progeny Software. A detailed medical history was acquired, and informed written consent was obtained from the legal guardian prior to the collection of peripheral blood samples. DNA extraction was performed using the DNSol Miniprep Kit from ROJETECHNOLOGIES, Tehran, Iran.

2.2. Molecular Investigations

Exome sequencing was conducted utilizing the NovaSeq 6000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) by the 3billion Inc. research team in Seoul, South Korea. This advanced sequencing technology facilitated the generation of high-quality sequence data, which were subsequently aligned to the Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37 (GRCh37) and the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS) of the mitochondrial genome. The alignment process ensured that the sequenced bases were accurately mapped to the reference genomes, thereby allowing for a comprehensive analysis of genetic variants present in the exome. All variants were analyzed using the EVIDENCE software for interpretation (10) and prioritization. This analysis followed the guidelines established by the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) and the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP), ensuring a standardized and rigorous approach to the interpretation of genetic variants (11). During the process of genetic counseling, relevant family history and prior clinical assessments were thoroughly reviewed, and clinically significant variants pertinent to the patient's primary clinical conditions were duly considered.

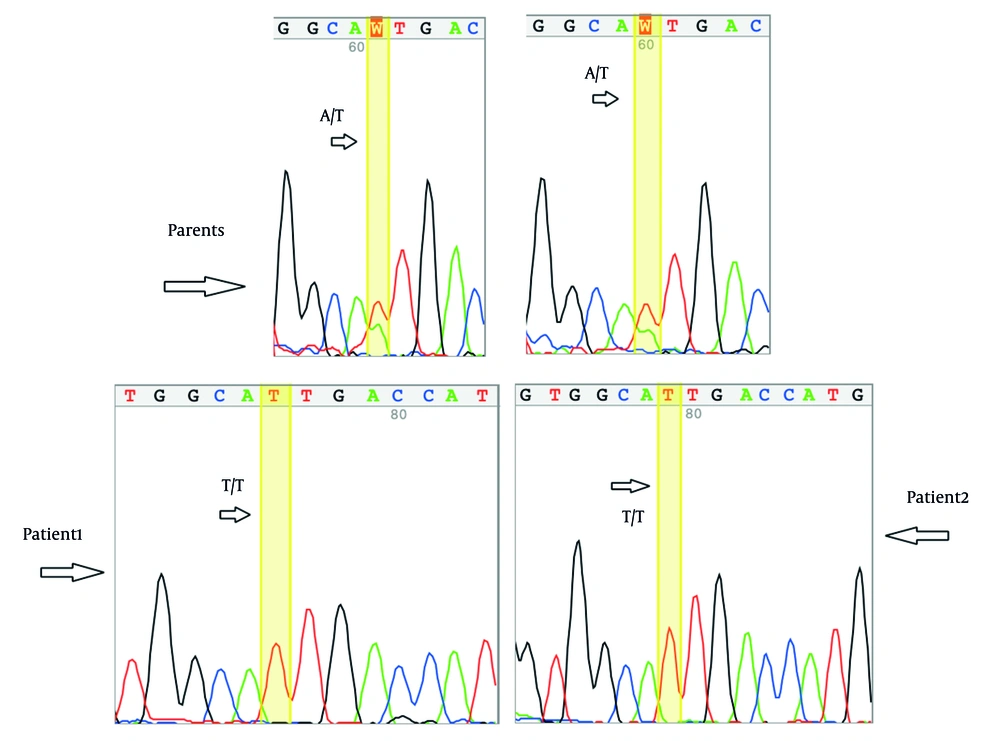

The suspected genetic variant was confirmed by Sanger sequencing, and co-segregation analysis was conducted on both affected and unaffected family members. Specific primers for the variant were designed with the Primer3 online tool (Primer3web, version 4.1.0) and validated through additional online tools, including Primer-BLAST (12) and MFEprimer3.1 (13). The primer sequences used in this study are provided in Table 1.

| Primer Name | Sequence (5’→3’) | Product Size |

|---|---|---|

| F-PMM2 | TCCAGGGTCACATCAGCAAT | 470 bp |

| R-PMM2 | GCCAAAACTACATGATTGCACG |

2.3. In Silico Analysis

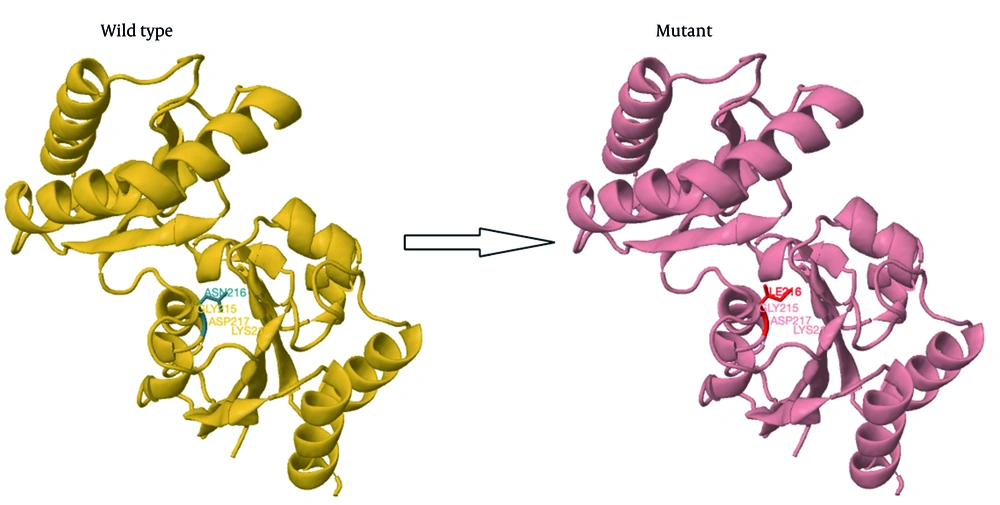

We utilized the Phyre2 Web Server to model the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the proteins and selected the highest quality model for subsequent analysis. Visualization, mutagenesis, and structural analysis were performed using PyMOL software (Version 2.2.3, Schrodinger, LLC.). Population allele frequency analysis was conducted using the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD v2.1.1). The variants' potential pathogenicity was evaluated by utilizing the following prediction tools: FATHMM and FATHMM-MKL (Functional Analysis through Hidden Markov Models, v2.3), LIST-S2, M-CAP (Mendelian Clinically Applicable Pathogenicity), Mutation Assessor, MutPred, PROVEAN (PROVEAN scores, v1.1), SIFT (Scale-Invariant Feature Transform) and SIFT4G, EIGEN and EIGENPC, BayesDel (addAF and noAF), MetaLR (e!Ensembl), MetaRNN, REVEL (Rare Exome Variant Ensemble Learner, e! Ensembl), DEOGEN2, and MetaSVM_score (the support vector machine (SVM) based on ensemble prediction score).

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

The proband (Figure 1) is an 18-year-old boy with severe intellectual disability (ID) and progressive movement disability. He experienced developmental delay (DD) and speech problems. He presents with a progressive movement disability and ataxia and cannot stand without assistance. He has facial features reminiscent of fragile X syndrome, including a long, thin face, prominent ears, prominent lips, and a broad nasal tip. He was previously molecularly tested for fragile X syndrome using Southern blot analysis, which resulted in a normal number (“28”) of CGG trinucleotide repeats in the FMR1 gene. His cytogenetic karyotyping showed a normal set of chromosomes, as 46, XY, consistent with an apparently normal male.

Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed normal size of cerebral ventricles and sulci, normal signal intensity of the cortex and white matter, no abnormality in the basal ganglia, internal capsule, corpus callosum, and thalamus, average signal intensity of brainstem and cerebellum, normal sella and pituitary, normal cerebellopontine angle area on each side, standard width of the internal acoustic meatus, normal development and pneumatization in paranasal sinuses and mastoid air cells, unremarkable orbital contents, and parasellar structures.

He has a younger brother, aged nine, with similar conditions, suffering from ID, DD, progressive movement disability, ataxia, and inability to stand or walk. They are the children of consanguineous parents. There is a family history of ID, movement disorder, seizure, ataxia, and abortions in the pedigree (Figure 1).

3.2. Molecular and In Silico Findings

Exome sequencing identified a deleterious homozygous variant in NM_000303.3 (PMM2):c.647A>T related to CDG disorders. The suspected genetic variant was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Figure 2), and co-segregation analysis was conducted. Table 2 lists the in silico findings regarding the identified variant. Based on ACMG and AMP (11) guidelines for variant interpretation, the identified variant meets the PP5, PM5, PP3, PM1, PM2, and PP1 criteria and has therefore been classified as a pathogenic variant.

| Gene | PMM2 |

|---|---|

| Variant genomic position | 16-8941588-A-T (GRCh37) |

| Variant cDNA position | NM_000303.3:c.647A>T |

| Variant protein change | NP_000294.1:p.Asn216Ile |

| Zygosity | Homozygous |

| Type of mutation | Missense |

| Allele frequency in gnomAD exome | Not applicable |

| Allele frequency in gnomAD genome | Not applicable |

| Bioinformatics tools showing damaging results | MetaLR, MetaRNN, BayesDel addAF, BayesDel noAF, MetaSVM, REVEL, DEOGEN2, MutPred, EIGEN, FATHMM, LIST-S2, M-CAP, Mutation Assessor, PROVEAN, EIGEN PC, FATHMM-MKL, LRT, SIFT, SIFT4G |

A structural modeling study showed that the p.Asn216Ile mutation causes the loss of hydrogen bonds between asparagine 216 and lysine 189, which may affect the protein's structure and function (Figure 3).

4. Discussion

Various disorders and symptoms are included in CDG, and the severity and prognosis vary significantly based on the specific type of CDG, even among individuals with the same type or within the same family. Additionally, most CDG types have only been identified in a small number of individuals, making it difficult for clinicians to develop a comprehensive understanding of the related symptoms and long-term outlook. These conditions generally become apparent during infancy (7).

This study identified a causative variant in the PMM2 gene related to PMM2-CDG in two siblings from a consanguineous family. The PMM2 gene encodes an enzyme called PMM2, which is involved in glycosylation and attaches groups of oligosaccharides to proteins. The process of glycosylation enhances the functional diversity of proteins. Mutations in the PMM2 gene lead to the production of an aberrant PMM2 enzyme with decreased activity, causing the generation of improper oligosaccharides that are attached to proteins. PMM2-CDG manifests a wide array of signs and symptoms, including but not limited to developmental delays, seizures, failure to thrive, and various organ dysfunctions. This diverse clinical presentation is believed to be attributable to the abnormal glycosylation of proteins, affecting multiple organs and tissues throughout the body (6).

Over 100 pathogenic gene variants have been documented to be associated with PMM2-CDG worldwide. About 80% of these variants are missense mutations, according to the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD). The R141H variant is noteworthy due to its high prevalence among PMM2-CDG patients globally. In contrast, other mutations, such as D65Y, are restricted to specific ethnic or geographical populations, being found exclusively in individuals of Iberian ancestry (14), and 26G>A (five alleles) and 548T>C (seven alleles) variants, which were found only in Scandinavian families (15). As in other Caucasian populations, p.R141H was the most frequent mutation (16). The identified variant (NM_000303.3:c.647A>T (NP_000294.1:p.Asn216Ile)) is located on exon 8 of 8 (the longest exon) of the PMM2 gene in the homozygous state (17). It was previously reported in 1997 by Matthijs et al. (18) as a compound heterozygous variant leading to CDG. Bjursell et al. also reported another pathogenic alternative variant in the same codon, causing different amino acid residues related to CDG (15).

PMM2-CDG, the most prevalent type of congenital disorder of glycosylation, has over 1000 cases reported worldwide (19). Patients diagnosed with this condition exhibit a diverse constellation of clinical symptoms, which can vary significantly in presentation and severity. These symptoms often encompass a range of physiological and developmental challenges, reflecting the complex nature of the disorder. Mutations in the PMM2 gene can give rise to a spectrum of phenotypes that range from mild to severe. In some cases, these mutations may lead to critical complications that result in neonatal death (20). In almost all patients, the nervous system is impacted (21), with symptoms ranging from an inability to walk to a lack of speech, poor comprehension, autistic features, and mild ID (22). PMM2-CDG is associated with a range of clinical manifestations, including failure to thrive, gastrointestinal symptoms, hypotonia, developmental delay, cerebellar atrophy, epilepsy, strabismus, and other movement disorders. Patients may also experience liver disease and coagulopathy, pericardial effusion, endocrinological manifestations such as hypothyroidism and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, as well as complications such as osteopenia and lipodystrophy (22). Severe forms of PMM2-CDG can be fatal in the first years of life, with a global mortality rate of up to 20% during this period (22).

In 2003, Neumann et al. (23) reported the first case of homozygosity for the 647A>T (N216I) variant of the PMM2 gene with CDG who developed postnatal macrosomia with an increase in weight, length, and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) above the 95th percentile within his first year of life. In contrast to other CDG patients, the child did not have abnormal fat pads or inverted nipples, but unusual eyebrows were present (23). The currently studied patients, who are products of consanguineous marriage, exhibit severe ID with progressive movement disability, developmental delay, speech problems, ataxia, and strabismus. These symptoms are consistent with previous studies (24-27); they did not have a history of macrosomia, but some facial features, including a long thin face, prominent ears, prominent lips, and a broad nasal tip, which were not noted previously, have been presented.

4.1. Conclusions

The findings provide broader insight into variants within the PMM2 gene and offer a thorough characterization of the phenotype related to this specific variant. The data have important applications for genetic diagnosis and counseling in relevant clinical contexts, as well as for identifying common gene variants associated with various ethnic groups. Additionally, this information could serve as a valuable resource in guiding therapeutic interventions.