1. Introduction

Testicular cancer is a rare neoplasm with an incidence of 2/100.000 men. Approximately, 5% to 6% of these are non-germ cell tumors (1), in which Leydig cell tumors (LCTs) are included. LCTs account for 0.8% to 3% of all testicular tumors in adults and 4% in prepubescent children with typical presentation between 5 to 10 and 25 to 35 years (2).

Although they are usually clinically benign, about 10% of the reported cases have been associated with a malignant course (3).

LCTs frequently appear as unilateral mass with variable endocrinal manifestations according to the age. In pre-pubescent patients, the signs of gynecomastia are detectable in 10% of the cases often associated with premature virilization, while in adults, gynecomastia is found in 20% to 40%, associated with decreased libido and infertility. In this report, we presented a case of Leydig cell tumor of the testis with uncommon clinical manifestations.

2. Case Presentation

A 53-year-old Caucasian man was sent to our attention by an endocrinologist for a bilateral gynecomastia and gynecodynia, requiring a urological evaluation. He had visible bilateral breast enlargement and the palpation examination demonstrated bilateral palpable, tender, firm, mobile, disc-like mound of tissues, just under the nipple-areolar complex. No nodules were found and the patients referred gynecodynia (pain during the palpation as well as spontaneous). The scrotum examination revealed a 2 cm soft palpable mass on the upper pole of the right testis. No other signs, including swelling of superficial lymph nodes were observed. Scrotal ultrasonography revealed a non-homogenous hypoechogenic tumoral mass in the right testis of 25 × 22 mm (Figure 1). General blood tests were negative; alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) were 4.6 ng/mL and < 1 mUI/mL, respectively (normal range: < 6 ng/mL and < 1.4 mIU/mL, respectively); hormonal setting showed high level of β-estradiol (73 pg/mL) and progesterone (1.56 ng/mL) (normal range: 10 - 40 pg/mL and 0.20 - 1.40 ng/mL, respectively). Total testosterone, FSH, LH, and prolactin were 0.96 ng/ml, 2.2 mIU/ml, 0.8 mU/mL, and 3.6 mg/mL, respectively (normal range: 2.10 - 7,50 ng/mL, 1.5-12.4 mIU/mL, 1,8 - 12,0 mIU/mL, and 2 - 18 ng/mL, respectively).

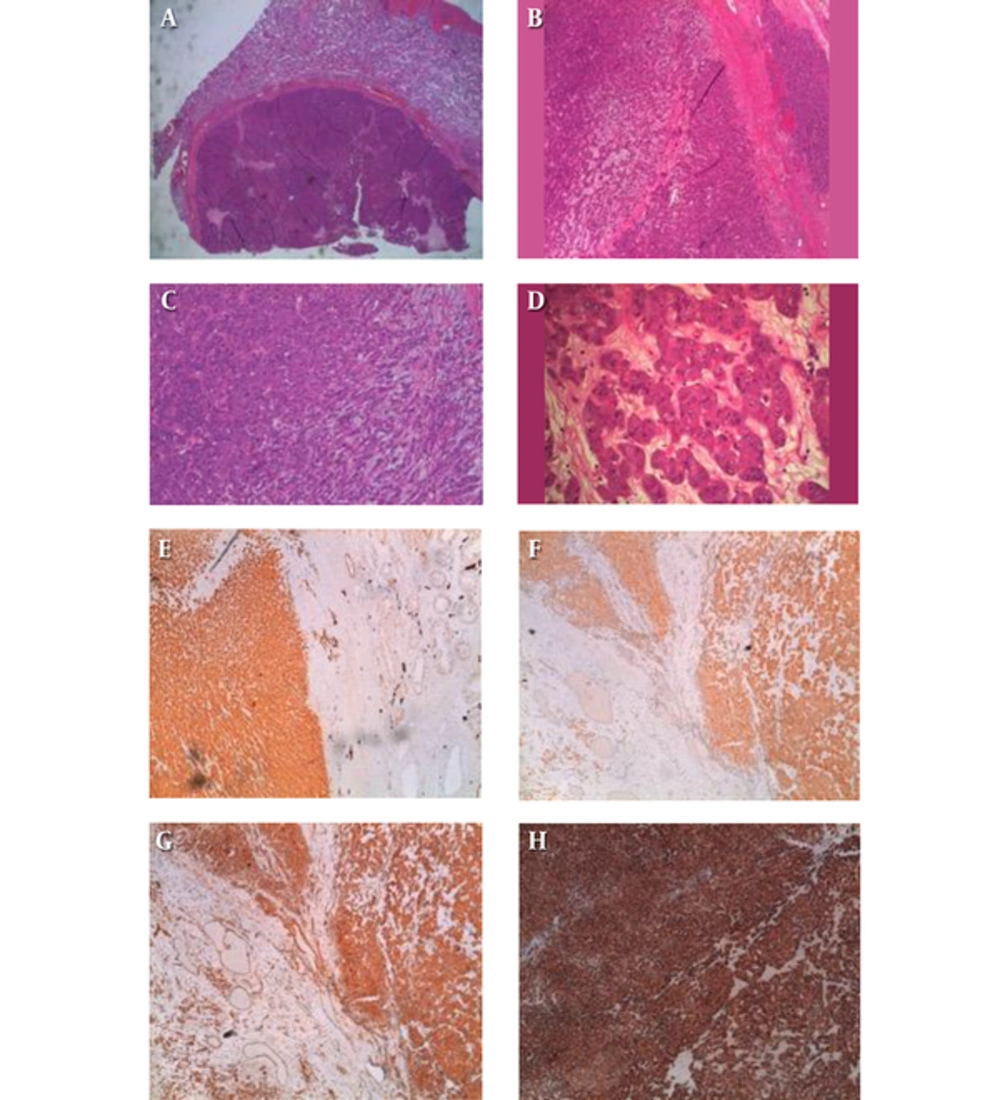

Abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan showed no abnormal findings. A radical approach was proposed to the patient. After obtaining an informed consent, right radical orchiectomy with testicular prosthesis implant was performed (Figure 1) with an uneventful postoperative course. The macroscopic examination showed a normal sized testicle with a soft, rubbery, and yellowish little mass on the upper pole. The hystopatological examination revealed a Leydig cell tumor with regular growing pattern without any signs of vascular or perineural invasion. Moreover, no necrotic areas were observed and the mitotic index was low (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical profile showed diffuse positive staining for Calretinin, Vimentin, and Chromogranine, and negative staining for Synaptophysin, Cytokeratin AE1/AE3, S100, CD99, and CKIT.

Clinically, the bilateral gynecodynia disappeared after surgery, while gynecomastia decreased considerably after 4 weeks. At the first week, all blood test results were normal. Only β-estradiol serum level was moderately increased. At 1 month follow up, the full body CT scan result was negative.

At 16 weeks, hormonal investigations showed a normal level of β–estradiol, AFP, and β-hCG, while gynecomastia still persisted even if reduced.

3. Discussion

Leydig cell tumors are uncommon. The etiology is unknown and it seems to be a heterogeneous disease. Some authors have reported a somatic activating mutation in the guanine nucleotide-binding protein α gene (4). Some others reported an inherited fumarate hydratase mutation, which appeared to cause tumor growth through the activation of the hypoxia pathway (5). Alterations in local stimuli, including mullerian-duct inhibitory factor, inhibin, growth factors, and temperature may also create favorable conditions for tumorigenesis (6). Berthold hypothesized a possible relationship between LCTs and finasteride (7).

The clinical presentation of LCTs is usually unilateral and only 10% is associated with a malignant course (3). In rare cases, a primary presentation in the epididymis could occur (8).

Although LCTs mostly affected men between 5 to 10 years and 25 to 35 years, in our case, the tumor presentation was in an adult man out of the typical age of incidence.

Normally, LCTs are incidental findings on scrotal ultrasonography performed for other indications (9) and the scrotum ultrasound is useful to confirm the suspected diagnosis of testicular tumor (4). In our case, the patient was symptomatic and the scrotal ultrasonography just supported the physical examination, revealing a non-homogenous hypoechoic tumoral mass in the right testis.

In patients with LCTs, the tumor markers (AFP, β-hCG, and lactate dehydrogenase) are commonly in the normal ranges with secretion of hormones (testosterone and estrogens). In our case, tumor markers were steadily negative (before and after surgery); estrogens were pre-operatively elevated and became normal few weeks after surgery. From a clinical perspective, gynecodynia disappeared almost soon, whereas ginecomastia shortly regressed.

Abdominal and pelvic CT scan and chest radiography are indicated if malignancy is suspected; however, in this case, the imaging was normal.

Commonly, the surgical management of LCTs is the radical orchiectomy (10, 11). Nevertheless, an organ sparing surgery was reported by Suardi in small LCTs with benign characteristics (12, 13).

The pathological exam with immunohistochemistry is essential for the final diagnosis. Even in our case, the histopathology confirmed the diagnosis without any suspect of malignancy. The results of immunoreactive tests were consistent with the existing literature (3). Although a long-term follow up is needed, we reported that after 16 months, the patient was free of disease with no evidence of recurrence or metastasis, with a normal serum levels of hormones and tumor markers, and without any signs of recurrence in the subsequent CT scan.

It is known that LCTs is a rare but possible disease; it has been yet described by many authors and for this reason, it is well known among the scientific community. There are a lot of reports and case series, including patients out of the common incidence range of age. In our study (Table 1), we found LCT’s presentation, consisting of gynecodynia and ginecomastia. While gynecomastia is already present in their studies, surprisingly no cases with gynecodynia are reported.

Leydig cell tumors are uncommon neoplasms, arising from gonadal stroma. The self-examination of testicles and ultrasonography exam appear to be a very important step for the diagnosis of testicular tumors. Also, other signs such as gynecomastia could be important to identify these types of tumor and they can influence the hormonal aspect of the patient.

| Study | Type of Study | Number of Cases | Age or Median Age | Gynecomastia (n) | Gynecodynia (n) | Malignant Course (n) (Medium Follow Up: 30 Months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gheorghisan-Galateanu AA. Leydig cell tumors of the testis: a case report. BMC Res. Notes. 2014; 7:656. | Case report | 1 | 29 y | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Tazi MF et al Leydig cell hyperplasia revealed by gynecomastia. Rev. Urol. 2008;10: 164 - 7. | Case report | 1 | 17 y | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sugimoto K, et al. A malignant Leydig cell tumor of the testis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2006;38: 291 - 2. | Case report | 1 | 68 y | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Libe R, et al. A rare cause of hypertestosteronemia in a 68-year-old patient)…activating mutation. J. Androl. 2012;33: 578 - 84. | Case series | 29 | 48 y (MA) | unspecified | 0 | 2 |

| Lejeune H et al. Origin, proliferation and differentiation of Leydig cells. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 1998;20:1 - 25. | Case report | 1 | 36 y | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Berthold D, et al. Finasteride-related Leydig cell tumour: report of a case and literature review. Andrologia. 2012;44 Suppl 1:836 - 7. | Case report | 1 | 40 y | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Albers P,et al. Guidelines on Testicular Cancer: 2015 Update. Eur. Urol. 2015;68:1054 - 68. | Case report | 1 | 60 y | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Our Case | Case report | 1 | 53 y | 1 | 1 | 0 |

In Leydig cell tumors, orchiectomy is the primary treatment, although an organ sparing approach for small lesion has been supported (13). Likewise, in the absence of any sign of malignancy, long-term follow up is necessary to exclude recurrence or metastasis.

(FIG.1: intraoperatory immage of right testis with tumor on theupper pole sectioned) (FIG.2: This nodular neoplasm shows a thick fibrous pseudo-capsule (1-4) and it is constituted by sheets, cords and solid nests of polygonal cells (3, 4), with scant edematous myxoid stroma (4). At higher magnification (4) epithelioid neoplastic cells have markedly eosinophilic granular cytoplasm with small vacuoles and round nuclei with prominent nucleoli. There are no atypical mitoses or necrosis.

The tumor cells are strongly and diffusely positive for Vimentin (c), with marked cytoplasm staining, while pancytokeratins are negative (not shown). Also Calretinin (a) and Inibine (d) show a diffuse and intense cytoplasmic stain in the solid cords of tumor cells. These three markers, joined to the morphological features, are sufficient to make diagnosis of Leydig cell tumor. Another immunohistochemical stain used was Chromogranin (b), which was positive, but not essential for diagnosis).