1. Context

One of the most important achievements in cancer research is the development of cancer immunotherapy (1, 2). The first cancer immunotherapy was performed by Coley, when he demonstrated that the administration of bacterial products could make tumor regression of inoperable neoplasms (3). Coley’s findings resulted in the beginning of cancer immunotherapy and, consequently in the 1960s, Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) was used to treat solid malignancies, such as bladder cancer. Subsequent research efforts in the 1970s and 1980s showed that activating lymphocytes with interleukin-2 (IL-2) could kill cancer cells in vitro (4). Large clinical trials investigated the therapeutic effects of cytokines for melanoma, and renal cell carcinoma in the 1980s (5-8). During this same period, it was demonstrated that interferon-α (IFN-α) has anti-tumor activity in melanoma (9-12).

Several monoclonal antibodies targeting cancer-associated proteins (such as HER2, EGFR, VEGF, and CD20) have been approved for the treatment of solid and hematologic neoplasms. These antibodies may opsonize cancer cells and induce their death by antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity or phagocytosis, in addition to antagonizing oncogenic pathways (13, 14). More recently, newer approaches in cancer immunotherapy have been developed, including administration of therapeutic cancer vaccines and adoptive cell transfer by chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy (15, 16). The finding of checkpoints in the immune machinery, such as CTL-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) resulted in the development of antibodies that inhibit these checkpoints, leading to T-cell activation (17, 18). Antibodies against these checkpoints have been approved in diverse malignancies, such as non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, renal cell cancer, and head and neck cancer (19-24). An important characteristic of immunotherapy is durable responses, which is supposedly due to the adaptive immune system memory, resulting in increased survival in some patients.

Regrettably, merely a subset of patients respond to immunotherapy modalities, and few patients respond for a durable time. Here, we review the possible genomic mechanisms of response and resistance to these therapies, which may lead to the selection of responders, who may benefit most from immunotherapy.

2. Evidence Acquisition

We searched PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science Core Collection with the following keywords: “Immunotherapy, Resistance, Response, Programmed cell death 1 receptor, CTLA-4, Cancer immunity, Tumor Genomics, and Somatic Mutations”. We also analyzed the references mentioned by the selected articles.

3. Results

A hallmark of cancer is the accumulation of somatic genetic alterations and loss of normal cellular regulatory control (25). The number of these somatic alterations is different between and within cancer types (26). Somatic mutations in tumors may be due to intrinsic infidelity of the DNA replication system, exposure to exogenous or endogenous mutagens, or impaired DNA repair. In some cancers, most somatic alterations are a consequence of environmental exposures, such as ultraviolet light in skin and smoking in lung cancers (27). In other cancers, there are abnormalities in DNA maintenance, such as impaired DNA mismatch repair in some colorectal cancers (28).

3.1. The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer

A cancer cell, similar to all cells of the body, is a descendent of a fertilized egg through mitotic cell division, and has a copy of diploid genome. The DNA of a tumor cell genome, similar to many normal cellular genomes, has differences from the original fertilized egg genome. These differences are known as somatic mutations, and varies from germline mutations, which are transmitted from parents to their children.

The somatic mutations in neoplastic cells include divers types of DNA change, including base substitutions, insertions, deletions, rearrangements, and copy number alterations. The tumor genome has also acquired epigenetic alterations, which change the chromatin structure and gene expression. The mutations in a malignant cell have accumulated during the lifetime of the patient with cancer. In normal cells, exogenous and endogenous mutagens continuously damage DNA. This DNA damage is mostly repaired, but a small subset becomes fixed mutations. In addition, there is a low intrinsic error rate in DNA replication machinery (29). The knowledge on somatic mutation rate in normal human cells is limited, but it is likely dependent on the specific somatic mutation class and various cell types (29).

It seems that the rate of somatic mutation is higher when a cancer cell shows phenotypic evidence of malignant change (30). This is evident at least in some cancers. For instance, there is an increased rate of single nucleotide change and small insertion/deletions at polynucleotide tracts in colorectal and endometrial cancers with impaired DNA mismatch repair (31). Other classes of “mutator phenotypes” may lead to abnormalities in chromosomal number and increased rate of chromosomal rearrangements (31). Increased mutation rate leads to increased DNA sequence diversity, on which selection acts. The catalogue of somatic mutations in a neoplastic cell is a record of all mutational processes throughout the life of the cancer patient.

Somatic mutations in a neoplastic genome may be classified as driver or passenger, based on its consequences on tumor development. Driver mutations lead to growth advantage of the cancer cell and have been selected positively during cancer development. They are located in the so called “cancer genes”. The number of driver mutations and aberrant cancer genes vary between different cancers (32). The rest of mutations are passengers and do not confer growth advantage. Passenger mutations do not have functional consequences and can happen during cell division (29).

The number of driver mutations in a malignancy is an area of active research, but on the basis of age-incidence statistics, it is likely that 5 to 7 driver mutations are required in common epithelial cancers, such as breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, whereas hematological cancers may require fewer rate-limiting events (29). Recent research have suggested that the number of positively selected cancer driver genes range from 1 in thyroid and testicular cancers to more than 10 in endometrial and colorectal cancers (33, 34). Although cancer genes frequently contain driver mutations, only a fraction of the somatic mutations detected in these genes are considered true drivers and the rest are passenger mutations (35).

3.2. Cancer Genome as a Driver of Tumor Immunity

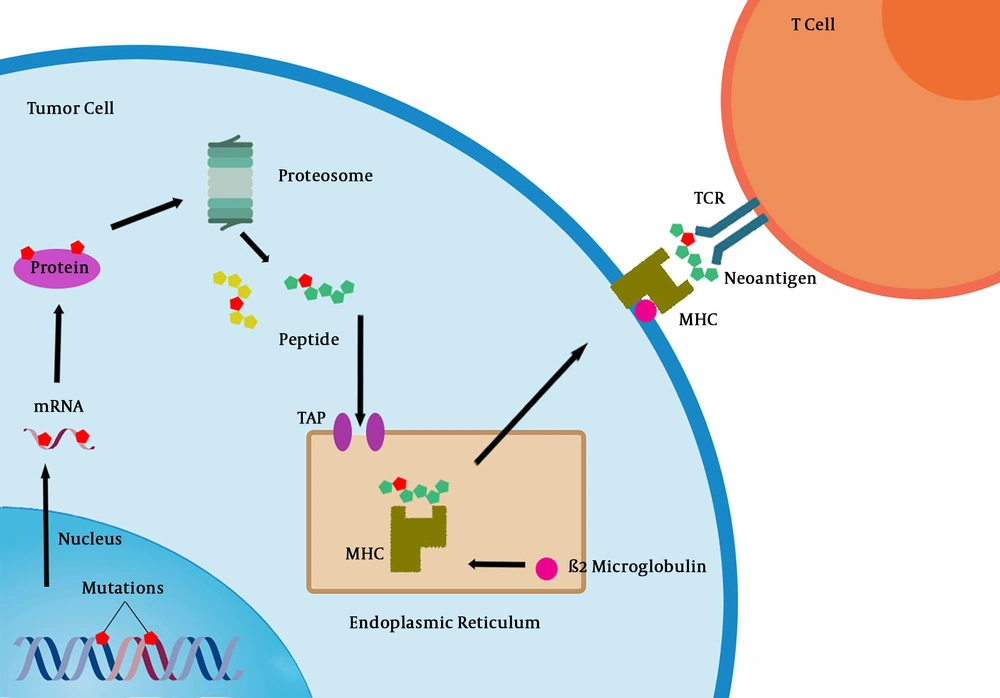

T cells that specifically recognize cancer-associated antigens are responsible for the immune system response against cancer. Nonsynonymous mutations, which are transcribed and translated into polypeptides may generate new epitopes (neoepitopes), which can lead to their presentation on major histocompatibility (MHC) class I molecules and subsequently recognized by the adaptive immune system (Figure 1) (36). However, even when T cell recognition occurs, they rarely confer protective immunity and cannot be used as a basis for therapy.

As demonstrated by mouse models, continued deletion of tumor cells expressing targets of T-cell recognition (immune editing) may help cancers evolve to avoid immune attack (37). In addition, factors in tumor microenvironment can modulate activated T cells and act as an “immunostat”. Despite these results, recent research on human cancer has shown that overcoming negative regulators of T cell responses in lymphoid tissue (checkpoints) or in the tumor (immunostat function) can reverse the failure of immune protection in most patients with cancer (38).

Results from mouse models have shown that point mutations may result in the production of mutant antigens, which induce T cells and elicit endogenous immunity or immunity with the administration of a therapeutic vaccine (39, 40). However, the recognition of mutant antigens by the immune system is not efficient. A study on a mouse model showed that only 10% of nonsynonymous point mutations encoded peptides that could be recognized with high affinity by MHC class I molecules and merely a subset of generated peptides were highly immunogenic after administration as cancer vaccine (41). Immunogenic peptides contain mutations that are exposed to the T-cell receptor or mutations that make new anchor that enhance the affinity to MHC class I molecules. In addition to point mutations, frameshift mutations, insertions, or deletions may generate new peptides (neoantigens) that are supposedly more immunogenic due to their more sequence divergence (42).

Protective immunity may be conferred by mutant peptides that can bind MHC class I or class II molecules (40, 43), although it is not certain whether CD4+ T cells have a role in anti-cancer immunity. CD4 expressing T cells help the cytotoxic CD8 positive T cells and B cell antibody production. In addition, they secret IFN-γ and induce an inflammatory response that is in favor of antitumor immunity (44). A study on human melanoma detected CD4+ T cell response against tumor neoantigens, suggesting that in addition to intratumoral CD8+ T cells, antigen-specific CD4+ T cells also have a role in cancer immunity (45). Several studies have determined the specificities of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) to tumor mutant epitopes by massively parallel sequencing and demonstrated that the adoptive transfer of antigen specific TILs into cancer patients is correlated with tumor regression (46-49). Together, these findings suggest that tumor mutanome is the main target of protective anti-cancer immunity and the large number of passenger mutations constitutes the most probable targets. Therefore, the mutational neoepitope load of a tumor is considered an important part of the cancer-immune set point (42).

It is important to consider the nature of the mutated genes, from which neoantigens derive and the frequency, with which they occur. It is clear that T cell responses against MHC class I-restricted and class II-restricted tumor neoantigens that are shared between subgroups of patients, sometimes occur (50, 51). At the same time, research on melanoma has shown that the majority of neoantigen-specific T cell responses are against mutated proteins unique to each tumor and likely without a key role in cellular transformation (45). This T cell preference toward patient-specific passenger mutations means that the development of personalized immunotherapies is possibly required for targeting neoantigens.

3.3. Resistance Mechanisms to Cancer Immunotherapy

With the finding of cancer immune checkpoints and the successful clinical implementation of checkpoint inhibitors, cancer treatment focus has changed from the tumor itself to the host’s immune machinery. It is important to note that host immune responses and cancer genomics are closely linked, as neoantigens driving from tumor mutations may shape immune responses (52). However, the heterogeneous and evolving tumor environment may render these responses ineffective.

Despite the unprecedented durable responses, the majority of patients treated with cancer immunotherapies do not respond to the therapy (primary resistance), and some patients relapse after an initial response (acquired resistance). With regard to resistance mechanisms to cancer immunotherapies, it is necessary to consider that in each cancer patient, the immune response is dynamic and evolves either due to the patient’s environmental and genetic factors or due to treatment interventions, such as surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. Many of these factors may affect anti-tumor immune responses and result in the establishment of resistance (53). Furthermore, human tumors differ considerably with regard to the constituents of their microenvironment, and this variability supposedly influences the capability of the T cells to recognize and respond to neoantigens. Comprehensive understanding of resistance mechanisms can lead to the discovery of biomarkers of response to immunotherapies, similar to biomarkers of response to other cancer therapies (54-57).

Primary resistance to immunotherapy can be a result of tumor cell intrinsic or extrinsic factors. The most obvious reason why a tumor would not respond to immunotherapy is the absence of tumor antigens being recognized by T cells (58). Alternatively, tumor antigens may exist in tumor cells, but the neoplastic cells may develop mechanisms to escape presenting them on their surface bound to MHC molecules, such as antigen presentation alterations (including changes in proteasome subunits or transporters associated with antigen processing [TAP]), β2-microglobulin alterations (required for MHC class I folding and transport to surface of cell), or MHC alterations (59).

Various clinical trials involving immune checkpoint inhibitors have identified different response markers. A study on pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, found that the proportion of tumor cells expressing PD-L1 affected the response rate (60). This trial showed that it is possible to use PD-L1 to select patients most likely to respond to the PD-1 inhibitor. Another study on atezolizumab, a PD-L1 inhibitor, showed that the likelihood of response was correlated with the immune cell infiltrate in the tumor, as well as PD-L1 expression on tumor cells (61). A study on pembrolizumab showed superiority of this treatment in patients with tumors that expressed PD-L1 on at least 50% of cancer cells (62).

The advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) technology has resulted in sequencing cancer genomes in an unprecedented ultra-fast and high-throughput manner. Using genomic approaches, several research groups have shown that there is a correlation between tumor mutation burden (TMB) and response to checkpoint therapy (63-67). As an example, in lung cancers mutations are often detected with a frequency of 0.1 to 100 per megabase (26). In non-small cell lung cancers with mutations in EGFR, ALK, ROS1, and MEK exon 14, TMB is usually low and these tumors usually do not respond well to check point inhibitors (68).

The association between tumor mutation (and neoantigen) load and immunotherapy response has been typically detected in tumors that have high mutational load (such as non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and renal carcinoma). But, some tumors (such as colorectal cancers) that generally have a significant number of mutations, usually do not respond to immunotherapy (26, 69). A likely reason is the extent of intratumoral heterogeneity, since bulk tumor sequencing might not fully show the spatial complexity of the tumor mutanome (70). As a heterogeneous population of subclones constitutes the tumor bulk, immune response against one neoantigen would target a subclonal population, thus leaving the remainder of the tumor intact.

Defects in mismatch repair generate a high mutation load. Research has shown that mismatch repair deficient tumors harbor considerably more somatic mutations compared to mismatch repair proficient tumors and respond better to anti-PD1 therapy (69, 71). Mutations in DNA repair genes may also affect immunotherapy response. A study showed that the loss of function mutations in BRCA2 gene were enriched in melanoma patients responsive to anti-PD1 blockade (66). Another study also detected mutations in DNA repair genes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer responsive to PD1 blockade (67). Therefore, even in cancers that generally have few mutations, such genomic analysis may detect a group of patients, who may benefit from immunotherapy.

4. Conclusions

Based on data gathered over the past few years, neoantigen specific T cells constitute a major “active component” for the success of cancer immunotherapies. The genetic damage that confers tumorigenic growth can also be targeted by the immune machinery to inhibit cancer development and progression. As expression of these neoantigens is tumor restricted; cancer immunotherapies offer the promise of specificity and safety. With further validation of experiments, genomics-based approaches can allow to select patients most likely to achieve durable responses to immunotherapy modalities.