1. Context

Different forms of irrational prescription include misuse, abuse, overuse, and polypharmacy. One of the serious global problems is irrational prescribing of medicines that can be considered as harmful and/or wasteful (1). While patients have the choice to select their doctors, doctors have the choice to decide on the kind of diagnosis and the quantity of health services patients consume. In other words, the doctor is the first gate to medicine use (2, 3). However, because of the patient’s inadequate information about medicine, the physician has the possibility to influence both the kind of diagnosis and the number of health services provided, as well as possibly the number of visits (4-8). Physician-induced demand clearly implies an effort to persuade patients to overuse services (4, 9-12). According to WHO reports, more than 50% of all medicines are inappropriately prescribed or sold, and nearly half of the patients do not take them appropriately (13). The report shows that patients are treated better in public sectors than private ones based on standard clinical guidelines (1). Ramezankhani et al. in a study on assessing the medicine prescriptions of health care centers, found out that prescription of medicine in the private sector was more than that of the public sector due to better monitoring programs (14).

Certain studies reported that inappropriate use and/or overuse of medicines wasted resources and led to health and economic consequences in patients (13, 15, 16). In providing evidence for induced demand, Reynolds and McKee conducted a study on factors influencing antibiotic prescription in China and found out that doctors overprescribe antibiotics because they share the income made by pharmaceutical suppliers as well as hospitals (17). Brekke and Kuhn evaluated the effects of advertising in pharmaceutical markets and suggested that the pharmaceutical advertisement may prompt unnecessary visits and patient demand to prescribe unnecessary medicine (18). Cockburn conducted a study on the effect of patients’ expectations for medication; it showed that when the physician found out that the patient expects medication, the possibility of providing the patient with an unnecessary prescription was 10 times more than when the physician thought that the patient did not expect any medication. The predictor of an unnecessary prescription was the physicians’ awareness of patients’ expectations (19).

The goal of this systematic review was to identify factors associated with irrational prescriptions of medicine. The review examined all research studies on unnecessary prescriptions, irrational prescription, physician-induced demand, and irrational use of medicine.

2. Evidence Acquisition

We searched the Cochrane database of systematic reviews (via Cochrane library), PubMed, Medline, Scopus, Science Direct, BMC, Scholar Google, and SID from 1980 up to October of 2016. We used the following keywords (Mesh-terms): Patient, Client, Physician-Patient Relations, Doctor-Patient Relations, Drug Prescriptions, General Practitioners, Prescription Drug Overuse, Medication Overuse, and Prescription Drugs.

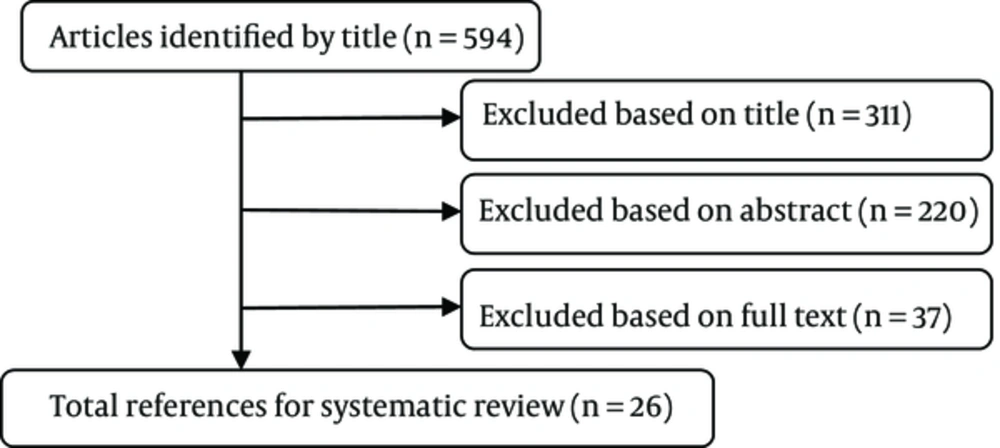

The searches were limited to the studies published in the English language on the following topics: unnecessary prescription, irrational prescription, irrational use of medicine, and induced demand for health service. A total of 594 papers were identified. At first we selected the appropriate studies based on the titles and abstracts. Then, the full-text copies of the selected papers were checked for possible relevance. The reference lists of all the selected articles were also checked as a backward search. We excluded studies in which the inclusion criteria were not explicit.

The quality of the selected papers was evaluated based on Grades of recommendation, assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) (20) consisting of 6 general items: 1) study design (qualitative or quantitative), 2) limitations (due to, for example, study design), 3) method (to state study design, setting and data of the study), 4) consistency of results, 5) indirectness (e.g. generalizability of the findings), and 6) precision (e.g. Sufficient data). The overall quality was considered to be high (6 out of 6) when the study provided precise, sufficient, and consistent results. The quality was considered to be 5 out of 6 when one of the factors was not satisfied. Thus, the papers, which acquired 6 or 5 out of 6, were included in the study. All the steps of the search were double checked by another reviewer, and consensus was obtained in a meeting over any inconsistencies (Figure 1). This systematic review left 26 papers.

3. Results

A total of 594 papers in the search process were screened for eligibility. Of these 594 papers, 26 papers were finally included. Table 1 displays summary information for each study (year, country/city, study design, and sample size) and Table 2 displays factors associated with irrational prescriptions of medicine.

| First Author | Years | Country/City | Designa | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilensky (12) | 1983 | Virginia | 4 | - |

| Cockburn (19) | 1997 | Australia | 3 | 22 GPs, 336 of their patients |

| Britten and Ukoumunne (21) | 1997 | London | 2 | 544 unselected patients consulting 15 GPs |

| Izumidia et al. (22) | 1999 | Japan | 3 | Not Mention |

| Britten and Ukoumunne (23) | 2000 | UK | 2 | 20 GPs, 35 consulting patients |

| Gosden et al. (15) | 2001 | Denmark | 1 | Six studies that compared fee-for-service, capitation, salary or target payments |

| Ely et al. (24) | 2002 | USA | 2 | 9 academic GPs, 14 family doctors, 2 medical librarians |

| Delattr and Dormont (5) | 2003 | Switzerland | 2 | 4500 French self-employed physicians |

| Madden et al. (25) | 2005 | Ireland | 5 | 20,466 individuals aged 16 years and over |

| Blomqvist and Leger (26) | 2005 | Singapore | 3 | Not Mention |

| Akkerman et al. (27) | 2005 | Netherlands | 3 | 146 GPs included all patients during a 4 week period in the winter of 2002/2003 |

| Doran et al. (28) | 2005 | Australia | 2 | 33 in-depth interviews from all adult age groups |

| Coenen et al. (29) | 2006 | Belgium | 3 | 85 Flemish GPs |

| Brekke and Kuhn (18) | 2006 | Germany | 3 | Two pharmaceutical firms |

| Manchikanti (30) | 2007 | Louisville | 4 | - |

| Devlin and Sarma (31) | 2008 | Canada | 3 | 2004 Canadian National Physician |

| Leonard et al. (32) | 2009 | Belgium | 1 | 25 papers |

| Reynolds and McKee (17) | 2009 | China | 2 | 24 patients, 11 village doctors, 26 health workers, two independent pharmacists, two village leaders, and three family planning officials |

| Dusansky and Koc (33) | 2010 | Austin | 3 | Not mention |

| Manchikanti (30) | 2010 | India | 2 | Three FGDs with 36 prescribers |

| Amporfu (34) | 2011 | Ghana | 3 | 2045 (1587patients received treatment from public hospitals and 458patients in private hospitals ) |

| Yousefi et al. (35) | 2012 | Iran | 2 | 15 GPs |

| Mao et al. (36) | 2013 | China | 4 | - |

| Teixeira Rodrigues et al. (37) | 2013 | Portugal | 1 | 35 papers |

| Soleymani et al. (38) | 2013 | Iran | 3 | 144 pharmacists |

| Chen et al. (39) | 2014 | Chin | 3 | 8,258 prescriptions in 2007 and 8,278 prescriptions in 2010, from 83 primary health care facilities |

| Clemens and Gottlieb (40) | 2014 | Canada | 2 | 2915 patients |

aStudy design: 1, systematic review; 2, qualitative; 3, quantitative; 4, review; 5, working paper.

| First Author (Country) | Demand to Prescribe | Patient’s Expectations | Inaccurate Diagnosis | Inadequate Awareness and Knowledge | Information Asymmetry | Poor Medical Education | Physician’s Attitude | Poor Medical Knowledge | Low Experience | Physician-to-Population Ratio | Increase Follow-Up Visits | Physician-Patient Relationship | Fee-for-Service | Insurance Reimbursements | Insurance Coverage | Out-of-Pocket | Medicine Subside | Medicine Advertisement | Ineffective Monitoring Programs | Lack of Regulation on Prescription | Financial Incentives | Lack of clinical guidance | Medicines Near-Expiry Dates or Expired | prescription Supervision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wilensky and Rossiter (12) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||

| Cockburn and Pit (19) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Britten and Ukoumunne (21) | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Izumidia et al. (22) | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Britten and Ukoumunne (23) | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Gosden et al. (15) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ely et al. (24) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Delattre and Dormont (5) | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Madden et al. (25) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Blomqvist andLeger (26) | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Akkerman et al. (27) | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Doran et al. (28) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coenen et al. (29) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brekke and Kuhn (18) | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Manchikanti (30) | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Devlin and Sarma (31) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leonard et al. (32) | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reynolds and McKee (17) | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Dusansky and Koc (33) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kotwani et al. (41) | + | + | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||

| Amporfu (34) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yousefi et al. (35) | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mao et al. (36) | + | + | + | + | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Teixeira Rodrigues (37) | + | + | + | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Soleymani et al. (38) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chen et al. (39) | + | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Clemens and Gottlieb (40) | + | + | + | + |

Four studies have been performed to investigate the physician- induced demand and its related factors (5, 12, 22, 34). Wilensky et al. in 1983, reviewed the findings from a series of studies on induced demand from the national medical care expenditure survey of the national center for health services research. They reported that induced demand was due to factors as demand for medical care by patients, physician-to-population ratio, increasing physician-initiated visits, physician-initiated health services, reimbursement system, insurance reimbursements, insurance coverage, and the share of the bill paid out-of-pocket by the patient (12). Also, Izumidia, in a study on examining the physician-induced demand hypothesis, adopted the expenditure function approach and showed that physician-population ratio and self-payment price are influencing factors initiating the demand for unnecessary services (22). Amporfu, in examining the supplier-induced demand, compared the changes in demands for health care services in the public and private hospitals and reported that unnecessary visits, especially follow-up visits, increased the irrational use of medicines (34).

Three studies have been conducted to examine the effects of patient’s expectations and demands for medication (19, 21, 29). Evidence suggests that prescribing behavior is influenced by patient’s expectations. Coenen et al. in a study on the impact of patient’s demand for prescription of antibiotic, showed that when GPs perceived patient’s demand, there was a higher incidence of prescription of antibiotic (29).

Three qualitative studies investigated knowledge, attitudes, and practices in physician prescription (17, 23, 24). Britten and Ukoumunne conducted interviews with participants to assess factors associated with decisions GPs make in prescribing medicine. Their results showed that inaccurate diagnosis and the patient’s inadequate cooperation with the physician in the visits are associated with inappropriate decisions in prescribing medicine (23). Ely et al. conducted interviews with participants to describe obstacles in the appropriate medical practice and reported that gap in knowledge and lack of physician awareness were 2 main obstacles for rational prescription (24). Reynolds et al. in a semi-structured interview, assessed knowledge, attitudes, and practices in prescribing antibiotics and reported that certain factors motivated the physicians to initiate an unnecessary prescription of antibiotic such as: speed up patient’s recovery, financial incentives, and incomplete national guidance (17).

Three studies have examined the impact of the payment system on physician practices (15, 25, 31). All 3 studies suggested that fee-for-service provides a higher quantity of health care services compared with physicians paid by capitation and salary. Madden et al. in a study on determining the relation between payment system for GPs and visiting rates, found out that the physicians who were paid on a fee-for-service method, behaved in their own economic self-interests and had higher visiting rates and more utilization of health care services (25).

Two studies assessed the interaction between insurance and health services consumption as well as demand (26, 33). Blomqvist and Leger in a study assessing the interaction between insurance and health services utilization, found out that in the context where the doctors were paid by capitation and patients who paid only part of the cost of their health services, the physician practice was significantly influenced by information asymmetry, patient cost sharing and fee-for-service payment method (26). Dusansky, in a study, assessed the effects of the interaction between insurance choice and medical service demand and reported that an increase in price for medical services led to a decrease in the request for medical services and also an increase in the request for more insurance coverage. However, the increase in insurance coverage increased the demand for medical services (33).

A total of 7 studies investigated effective factors on irrational prescription of medicine (27, 30, 35-38, 41). Akkerman et al. in a study, assessed determining factors of over-prescribing of antibiotics using the Dutch national guidelines as a benchmark. They reported that overestimation of the symptoms by physicians and patients’ expectations could be the most important determinants of overprescribing (27). Manchikanti reviewed the facts on the overuse of medicine and found out that lack of education about the factors involved in unnecessary medication for physicians, pharmacists, and the public; and ineffective monitoring programs were important factors for overuse of medicine (30). Kotwani et al. conducted a qualitative study to examine the factors effective in prescribing antibiotics by primary care physicians in Delhi. They used 3 focus group discussions to explore the views of primary care physicians in both private and public sectors. They found out that the significant factors for antibiotic prescriptions were inaccurate diagnosis, patient’s expectation and demand, sustainability in practice, financial incentives, and physician’s inadequate knowledge. They reported 2 additional factors in the public sector, such as: prescribing overstocked and near-expiry date antibiotics to save money as well as spending inadequate time with the patient to visit more patients (41).

Yousefi et al. in a study, conducted interviews with GPs to assess effective reasons on the irrational prescription of Corticosteroids and found that the effective factors in irrational prescription were lack of physician awareness, physician-patient relationship, inadequate accessibility of alternative medicines, and poor supervision on the prescriptions (35). Mao et al. in a review study, discussed the situation of irrational use of medicines, suggested that lack of knowledge in providers and patients fee-for-service payment were the factors involved in the irrational use of medicine (36).

Teixeira Rodrigues et al. in a systematic review about the physician’s opinions on influencing factors for antibiotic prescribing, found out that physician’s attitudes, patients’ expectations, demand for previous clinical practice, poor education in university, lack of continuous medical education and years of experience, and clinical practice could interfere with appropriate prescription (37). Soleymani et al. in a cross‑sectional study, used a pre‑designed questionnaire in a convenient sampling of pharmacists to analyze the pharmacists’ viewpoints about the main factors of rational use of medicine and reported that the most important determinant was the lack of public knowledge and awareness about the appropriate use of medicines (38).

Two studies have examined the impact of economics incentives on the physician’s behavior (39, 40). Clemens et al. in a study, developed a model of physicians’ joint supply and investment decisions and concluded that the health care supply was influenced by patient’s demand, fee-for-service, out-of-pocket, and financial incentives (40).

Brekkea et al. in a study, investigated the effects of advertising on the use of medicine in the market. Their results showed that advertising could increase unnecessary visits to the physicians overloading physician’s services, and consequently initiating unnecessary prescription (18).

Leonard et al. in a systematic review, assessed the correlation between doctor density and health care consumption. The results showed a significant positive correlation between doctor density and health care consumption. An increase in the number of doctors increased physician-induced demand and increased follow-up visits (32).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify factors leading to irrational prescriptions of medicine. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review study that considered factors involved in both irrational prescription and induced demand for medication in health care services. The combined results of 26 studies indicated 3 main categories: 3 patient’s factors, 9 physician’s factors, and 12 institutional and political factors.

The patient’s factors were patient’s expectations, demand to prescribe, and poor medical knowledge. Thus, we recommend that patients or the community could be targeted for educational interventions to modify the 3 factors. Such interventions might include education to increase medical awareness of patients (35, 41), improve pharmaceutical knowledge (38), and change the patient’s attitude based on an understanding of his beliefs (17). Ahmed, in 2009, suggested that there is a need to health education interventions to reduce the knowledge gap between the doctors and patient, and empower the patients to make choices and decisions about their treatment (16).

Physician’s factors were inaccurate diagnosis, inadequate awareness and knowledge, low experience, information asymmetry, poor medical education, physician’s attitude, physician-to-population ratio, increased follow-up visits, and physician-patient relationship. We recommend effective interventions to promote the best practice (17), improve diagnostic accuracy, enhance patient-centered consulting skills (27), optimize prescribing (29), promote the patient health (32), and upgrade knowledge and awareness through continuing medical educations (41). Yousefi, in 2012, suggested that interventions such as workshops, focused on training programs based on problem-solving approach and training programs for pharmacists can be useful in reducing irrational prescriptions (35).

The institutional and political factors were fee-for-service, out-of-pocket payment, financial incentives, insurance reimbursements, insurance coverage, medicine subside, medicine advertisement, ineffective monitoring programs, regulation on prescription, prescription supervision, lack of clinical guidance, and medicines near-expire dates or expired.

Thus, we recommend to consider multi-faceted strategies to change payment system from fee-for-service method to capitation (15, 25), prescribe base on clinical guidelines (29, 32, 35, 36, 42), develop a policy to establish a certain number of patient visits per week (31), control and establish stricter rules, regulations and policies for prescription (16, 35, 36, 38, 41), evaluate the legitimacy of a follow-up visit (32), remove perverse economics incentives (17, 36), improve surveillance (17, 38), prescribe based on essential drug lists (35, 36), and finance medicine policies (38).

Mao, in 2013, suggested some necessary strategies in the prevention of irrational prescription. The strategies, including separating medicines sales from service providing, prepayment mechanism based on fee-for-service and prescription based on clinical guidelines, and essential medicine list (36).

This review has 2 limitations. First, the search was limited to articles published in English. Second, we might have missed relevant unpublished studies.

It can be concluded that the irrational/unnecessary prescription of medicine was influenced by many different factors, which were related to the patient, physician, and institution. Thus to prevent irrational/unnecessary prescription, one needs to consider all the involved factors and take measures to eliminate or reduce their impacts on the health care system.