1. Introduction

Chondroblastoma is a rare bone tumor comprising less than 1%-3% of primary bone tumors, which has no predilection to a specific bone, and it occurs characteristically in the epiphyses and secondary ossification centers of long bones, particularly in the femur, humerus, and tibia (1-5). Because the cortical bone, articular cartilage, and joint capsule usually act as natural barriers preventing tumor extension (6), it is unusual for chondroblastoma to exhibit cortical erosion or intraarticular invasion. Approximately 20% of these tumors occur in either the calcaneus or talus, and occurrence of an associated cystic lesion has been reported highly to 33% (7). Although navicularchondroblastoma has been reported in the literature (1), it is very rare(4). Davila et al. estimated a series of 211 patients with hands and feet chondroblastomas, and no lesion was reported in the navicularbone (8). In a series of 332 patients with chondroblastoma, of the 42 feet cases, only one lesion was found in the navicularbone by Fink et al.(1).

2. Case Presentation

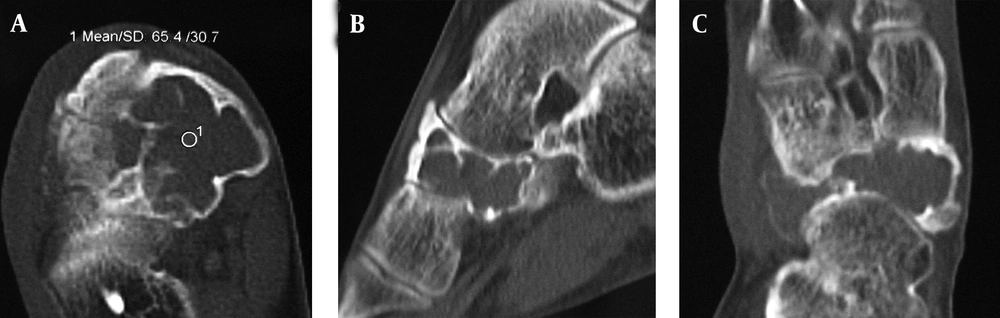

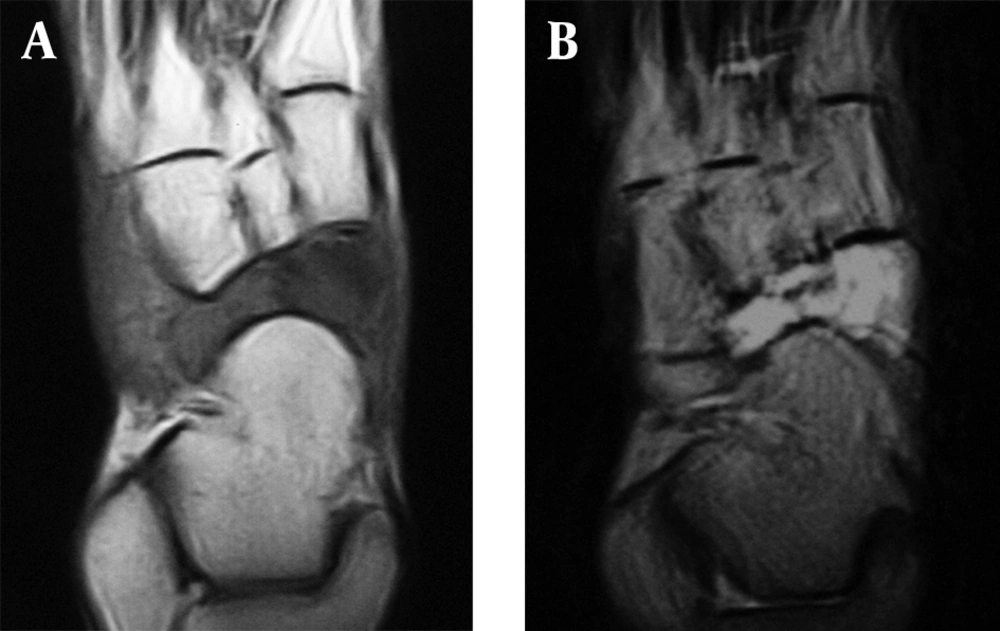

A 24-year-old man complained of a 24-month history of pain and swelling in the right foot after a minor twisting injury. The past medical history was significant for repeated “ankle sprains”. The pain was present at rest and it was generalized around the ankle. He also complained of mechanical pain in themidfoot. Despite the symptoms, he was working and playing table tennis. Physical examination revealed mild swelling on the medial aspect of his right midfoot. A firm, moderately tender mass about 2 × 1cm was palpated. The ankle had a full range of motion and limited inversion and eversion secondary to pain.X-rays showed a large expansile cyst in the right navicularbone with sclerotic margins and septation (Figure 1). The lesion appeared to invade all of the navicular bone, with questionable extension into the neighboring joint. Later, for further diagnosis, computerized tomography (CT) was chosen and it showed a large defect with scalloped, septated, sclerotic, and well-defined margins (Figure 2A, B, C). Most of the navicularbone was invaded with no evidence of calcification. There was a 2 ×4cm cortical thinning following cortical defectat the level of the talonavicular joint facet and cuneonavicular joint facet. A lesion instead of the normal bone architecture with no soft-tissue component was detected on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging with low signal intensity in spin echo (SE) T1-weighted image and high signal intensity in turbo spin echo (TSE) T1-weighted image with short timeinversion recovery (STIR) (Figure 3A and B).Because the patient underwent the MR scan with a low field MR equipment, we only could acquire the low quality MR images. However, based on the MR images we could know about the character of the lesion.

Axial (A), Sagittal (B) and Coronal (C)CT images show an expansile lesion of the navicular bone, with a large defect with scalloped, septated, sclerotic, and well-defined margins. There was cortical deficit at the level of the talonavicular joint facet and cuneonavicular joint facet. The CT number of the lesion was 65.4Hounsfield units.

Coronal T1-SE-weighted (A) and short time inversion recovery (STIR) MR (B) images of the navicular bone show unequal signal. Note the well-defined low T1 intensity signal, and the high signal intensity. (T1-SE: FOV: 180mm; TR: 512 ms; TE: 11 ms; Flap angle:90°; Bandwidth:150Hz/Px; T1-TSE-STIR: FOV:180mm; TR: 3700 ms; TE: 38 ms; TI: 160 ms; Flap angle:150°; Bandwidth:191Hz/Px)

The lesion was extensiveandit nearly replaced the navicular bone completely. In addition, it wasconcurrentwith medial soft tissue involvement and joint facet deficitalong the medial aspect of the bone. Therefore, the initial diagnosis was giant cell tumor or aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC). However, chondroblastoma was confirmed by pathology (Figure 4). At the end, the tumor was excised and operated by using internal fixation with bone graft. The patient was followed up by plain radiography at three-monthly intervals for two years, including the lung and foot(Figure 5). There was no evidence of recurrence 1 year later

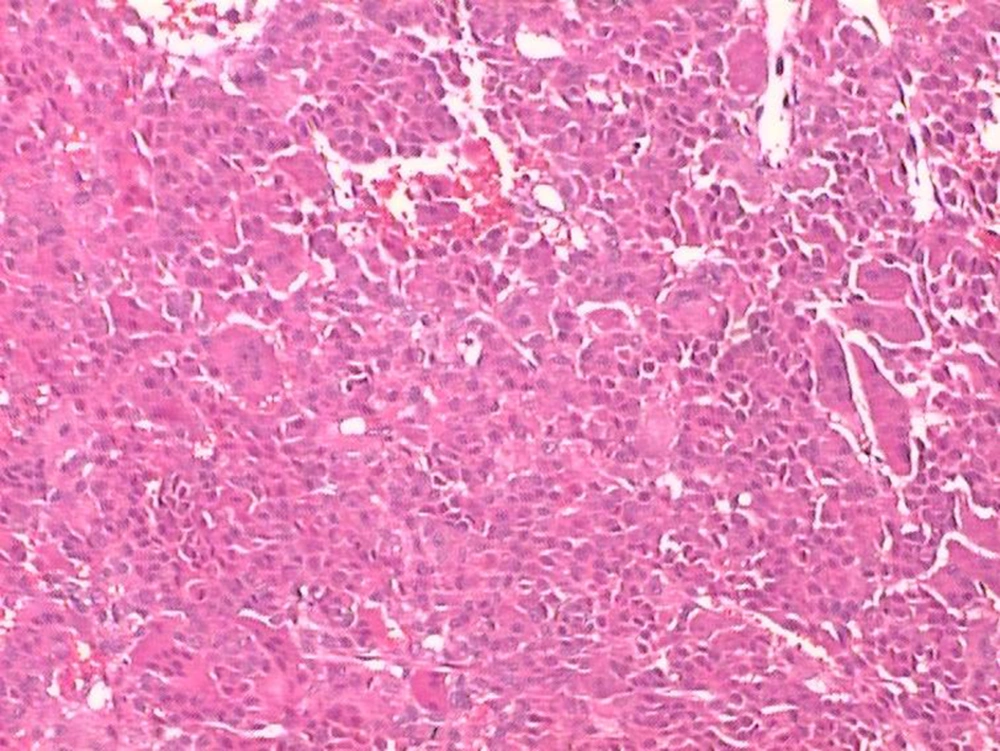

Histopathology of the curettage specimen shows polygonal-shaped chondroblasts that are large and closely packed with a central, basophilic, characteristically grooved nucleus and translucent cytoplasm. Scattered throughout are small, nucleated giant cells and islands of more mature cartilage (Hematoxylin and Eosin ×40).

3. Discussion

Classic chondroblastoma has been described as a tumor of the epiphysis of long bones in skeletally immature individuals and it comprises1%-3% incidence of all bone tumors (1-3, 9). Generally, chondroblastoma can behave aggressively to the local bone, soft tissue, but rarely the joints (1). Usually, this tumor grows rarely in the foot (1). It was reported that chondroblastoma of the feet constituted 0.47% of all tumors reviewed and it represented 10.4% of all chondroblastoma cases (1, 4, 8). To the best of our knowledge, only one prior study has described a case of chondroblastoma in the navicularbone (1). The most common clinical feature is pain, especially in pathologic fracture, and it usually takes several months before presentation (7). Approximately, 20%-50% of the patients have a history of trauma (10, 11). The common clinical findings are localized swelling, a decreased range of motion and tenderness on direct palpation. About 1-13% of the patients present with pathological fracture (9, 10, 12).Radiologically, chondroblastoma is generally radiolucent, round-shaped, with a well-defined, thin sclerotic rim, and erosion of the epiphysis or neighboring metaphysis of a long bone (13). The surrounding cortical bone may be intact or expanded, but breakthrough is not usual. A scattered, stippled calcification appearance or a sparsely trabeculated pattern can sometimes be seen (3). The appearance of chondroblastoma in the hands and feet was similar to that described in the long bones: a lytic lesion with sclerotic margins, bony expansion, matrix mineralization, and occasional septation(8). The greatly expanding inner lesion can result in the formation of the mass in this tumor.In contrast to long bones in which pathologic fracture is an uncommon characteristic of tumor (occurring in 1%-13% of the patients)(2, 13), pathologic subchondral fracture of chondroblastomais frequent in the foot, but it is not always obvious on plain films (8, 13). Though joint erosion in bony tumors is very rare (1), encroachment of the joint is not rare in the tarsal bone (8). As in the present study, the lesion expanded greatly and destroyed the articular surface of the talonavicular and cuneonavicularjoints. Conventional radiography is an initial examination tool of the painful region. The encroachment of tarsal bones with chondroblastomais usually located in secondary ossification centers, with cortical expansion without associated erosive changes in the cortex (4). In spite of the similarity between chondroblastoma and ABC or giant cell tumor, the diagnosis can be made. Firstly, the sex and age of the patient should be considered. In the foot, the incidence is greater in men and the age is older than that with chondroblastoma elsewhere (7, 8, 13, 14). In this case report, the age of the patient was in the usual age range, 24 years old (the usual age of chondroblastoma is 10-30 years), while 80% of ABCs present before the age of 20 (14) and giant cell tumor present after 30 (15). Secondly, the lesion of chondroblastomais slightly expansible with a well-defined margin and a sclerotic rim (13). However, the lesion of ABC and giant cell tumor often appears more aggressively with an exaggeration of bone expansion and cortical thinning following cortical deficit (14). As for this tumor, the lesion presented similar to ABC and giant cell tumor, which could cause misdiagnosis.CT and MRI techniques are helpful in making the differential diagnosis. On CT, the degree of calcification and septation may be identified to analyze. On the other hand, enhanced bone details and cortical continuity could be evaluated on CT that provides the size and extension of the lesion in the cortical bone and it is helpful for surgery. MR findings can perspicuously show this tumor as low signals in T1-weighted images, with less inhomogeneity, and high signals in T2-weighted images, which is similar to the long bones (16). Soft tissue mass and the medulla invasion can be evaluated on MR imaging. It is a helpful imaging tool in describing the extent of the tumor, and finding pathologic subchondral fracture of chondroblastoma in the foot (16).Microscopic examination of this tumor reveals typical polygonal-shaped chondroblasts and osteoclast-like giant cells. The chondroblasts are large and closely packed with a central, basophilic, characteristically grooved nucleus and translucent cytoplasm. Scattered throughout are small, nucleated giant cells and islands of more mature cartilage. Calcification usually presents in most lesions, and it has an intercellular distribution with a "chicken wire" or "picket fence" appearance (12). However, no calcification was discovered in the present tumor.

Chondroblastoma should be treated surgically when detected as the tumor may exhibit an aggressive behavior despite its benign nature. Surgical treatment includes curettage and resection (3)that creates a defectin conjunction with bone grafting using internal fixation. Though it is reported that the outcome of this tumor is good after operating, chondroblastomas have the danger of recurrence and pulmonary metastases (5, 17). To prevent theseabove, the close follow-up is warranted. Suggestion should be given to perform the plain radiography of the lung and foot.In conclusion, chondroblastoma of the navicularbone is a rare benign bone tumor. The present reportis the first detailed imaging presentation ofchondroblastoma of the navicular bone. This lesion was extensive, with near complete replacement of the navicularbone without calcification. It is difficult to make the differential diagnoses of chondroblastoma from primary giant cell tumor and ABC. The correct diagnosis and treatment should be made by cooperation of radiologists, bone pathologists and orthopedic surgeons.