1. Background

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a relatively common sequela complicating the clinical course of patients with end stage liver diseases (1, 2). HE is clinically characterized with a wide range of neurological and psychological dysfunctions encompassing changes in attitude, impaired speech abilities, sleep disorders, and locomotor dysfunction (2, 3). Overt HE generally represents a distinct condition, which is easily identifiable based on clinical presentations (4, 5). However, silent or minimal HE may raise a diagnostic challenge for physicians.

HE has been described in association with various hepatitis viruses including hepatitis C (HCV), hepatitis B (HBV), hepatitis E (HEV), and hepatitis A (HAV) (6-11). Thus, overt HE has been noted in 7.4% of patients with HAV infection (11). Beside overt HE, the incidence of minimal HE in patients with acute viral hepatitis has been associated with a variety of complications (12). The subclinical HE remains undiagnosed in a considerable ratio of patients depriving them from appropriate treatments. On the other hand, undiagnosed HE may progress to overt HE and endanger patients’ lives (13).

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a sensitive and rapid method to identify cerebral disorders by recording brain electrical signals. This method provides a sensitive and reliable procedure for screening neurophysiological disorders (14). Abnormal EEG has been noted as an early diagnostic sign for brain dysfunction in the absence of overt or minimal HE (15, 16). There is a shortage on studies concerned with EEG abnormalities in neurologically asymptomatic children with HAV infection.

2. Objectives

In the present study, we evaluated EEG patterns in 45 HAV infected and 45 healthy children admitted to our hospital during a 12-month period.

3. Methods

3.1. Patients

Forty-five HAV infected children admitted to our hospital, along with 45 age and sex matched healthy children, were included in the study. Healthy subjects were selected from children showing no signs of any systemic disorder and representing normal results for basic laboratory tests (i.e. complete blood count, liver enzymes, fasting blood sugar, and thyroid hormones). This study was performed in the pediatric ward of Amir-Al-Momenin Hospital of Zabol city, Sistan and Baluchestan province of Iran. The patients and healthy controls were recruited during a 12-month period from June 2016 to June 2017. After a comprehensive interview for investigating any history of mental disorders in the family, which was the main exclusion criterion, an informed consent was acquired from the children’s parents. Ten milliliter blood samples were taken for biochemical and hepatic enzymes studies.

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

Those children with any sign of coagulopathies, history of brain disorders in the family, systemic disorders, history of receiving neurotoxic drugs, and presenting with neurological or psychological symptoms were excluded.

3.3. EEG Assessment

EEG was performed in rest condition while the patients were awake and closed-eyes using Neurofax EEG-4518 (Nihon Kohden, Tokyo, Japan), as previously described (17). The 10 - 20 international system was applied. Five electrodes were attached to the skin surface at T3, T4, O1, O2, and Cz locations. The assessment was carried out in 0.53 - 35 Hz frequency for 100 seconds.

3.4. Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed by SPSS V. 19 software. Data distribution was checked by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Chi-square test and Independent Sample Student t-test were used for univariate analyses. Significance level was considered at P < 0.05.

4. Results

Out of 45 patients, males and females comprised of 18 (40%) and 27 (60%), respectively. In heathy controls, 16 (35.5%) and 29 (64.5%) subjects were males and females, respectively. The mean ages in HAV infected and healthy children were obtained 71 ± 38.1 and 92.2 ± 32 months, respectively (P = 0.1). Hemoglobin, prothrombin time (PT), partial thromboplastin time (PTT), hepatic enzyme levels, total and direct bilirubin levels, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were significantly different between infected and healthy children (Table 1).

| Parameters | HAV- Infected Children (N = 45) | Healthy Children (N = 45) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum - Maximum | Mean (SD) | Minimum - Maximum | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (mon) | 2 - 156 | 71 (38.1) | 5 - 144 | 92.2 (32) | 0.1 |

| Weight (kg) | 6 - 42 | 19.2 (7.6) | 10 - 40 | 20.7 (7.6) | 0.2 |

| White blood cell count (×103/µL) | 4 - 18.5 | 8.8 (2.9) | 5.8 - 12.9 | 8.8 (2.6) | 0.6 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 7 - 14.6 | 11.3 (1.3) | 9.9 - 14.1 | 12.3 (1.04) | 0.003 |

| Platelet (×103/µL) | 173 - 721 | 344.2 (145) | 143 - 540 | 296.7 (114.1) | 0.5 |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 13 - 17 | 13.5 (1.1) | 10 - 14 | 12.6 (1.07) | 0.04 |

| Partial thromboplastin time (s) | 29 - 48 | 37.4 (5.6) | 30 - 45 | 33.7 (4.9) | 0.01 |

| Aspartate amino transferase (IU/L) | 20 - 3350 | 582.3 (670.5) | 20 - 45 | 32.4 (9.6) | 0.001 |

| Alanine amino transferase (IU/L) | 10 - 4350 | 774.6 (899.6) | 12 - 38 | 23.6 (7.5) | < 0.001 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 240 - 6360 | 1027.9 (929.8) | 211 - 575 | 389 (123.8) | < 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.8 - 6.8 | 4.1 (1) | 3.2 - 5 | 4.4 (0.5) | 0.8 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5 - 9.6 | 7.4 (0.9) | 5.8 - 8.2 | 7 (0.8) | 0.4 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.5 - 10.7 | 3.5 (2.9) | 0.5 - 2 | 0.9 (0.4) | < 0.001 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 - 4.1 | 1.2 (1) | 0.1 - 1 | 0.29 (0.25) | < 0.001 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 4 - 61 | 24.6 (14) | 1 - 20 | 8.4 (6.7) | < 0.001 |

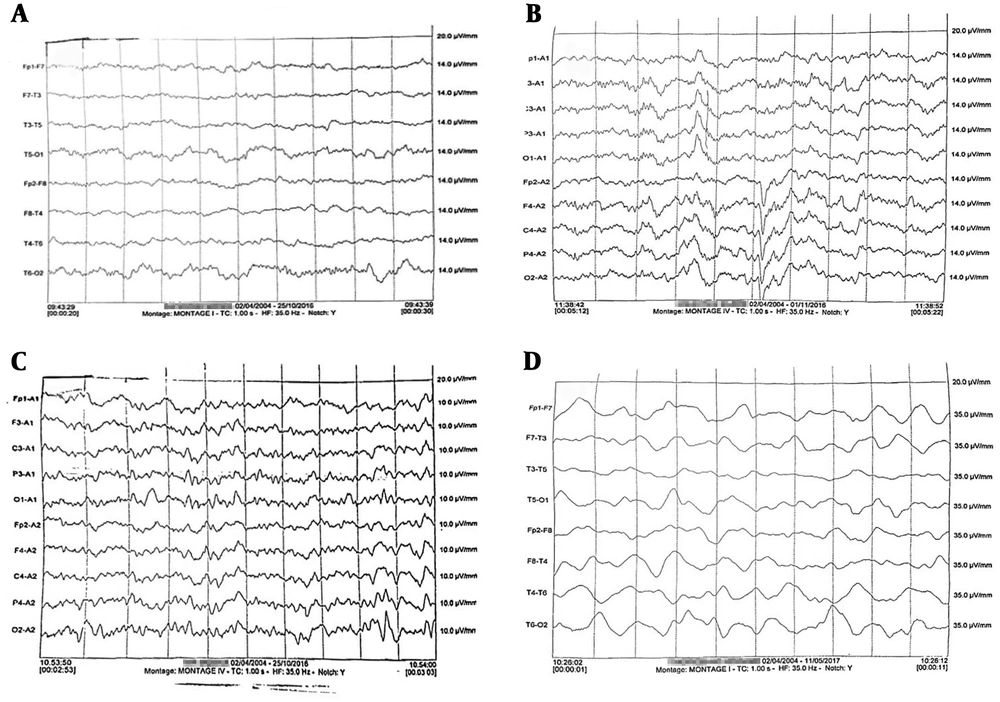

Abnormal encephalogram pattern was recorded in 16 (35.6%) HAV infected patients (Figure 1). EEG abnormality was not detected in any healthy child (P = 0.02). Irregular spikes along with alpha waves were the most frequent patterns (13 out of 16, 81.2%). One patient (6.3%) showed delta wave, and two patients (12.5%) represented with triphasic waves.

Electroencephalography results related to children with hepatitis A infection. A, normal regular alpha waves observed in 29/45 patients; B, spike and alpha waves pattern which was seen in 13 out of 16 patients with abnormal EEG; C, tri-phasic waves observed in two cases; and D, delta wave which was detected in one 4-year old female child.

Most of our patients had abnormally high (i.e. > 40 IU/L (18)) hepatic enzymes levels (41/45, 91.1% for aspartate amino transferase (AST), and 37/45, 82.2% for alanine amino transferase (ALT)). Also, 10 patients (22.2%) had abnormally high alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels. Serum albumin, total protein, total bilirubin, and direct bilirubin measurements showed abnormally high levels in 3 (6.7%), 9 (20%), and 30 (66.7%) patients, respectively.

There was no significant difference between males and females regarding irregular EEG patterns. However, the mean age of patients with irregular EEG was significantly higher (89.6 ± 35.2 months) than the patients with normal EEG (60.7 ± 36.2 months, P = 0.01). Although a considerable number of patients with abnormal EEG pattern had abnormally high AST (15/16) and ALT (14/16), the means of neither AST nor ALT were significantly different comparing patients with normal (535.9 ± 571.8 IU/L and 660.1 ± 649.8 IU/L, respectively) or abnormal (666.4 ± 834.7 IU/L and 982.1 ± 1230.7 IU/L, respectively) EEG pattern (Table 2).

| Parameters | Electroencephalography | Normal Range | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal (N = 29) | Abnormal (N = 16) | |||

| Age (years) | - | 0.04 | ||

| < 7 | 23 | 8 | ||

| > 7 | 6 | 8 | ||

| Sex | - | 0.3a | ||

| Male | 13 | 5 | ||

| Female | 16 | 11 | ||

| Aspartate amino transferase (IU/L) | 5 - 40 | 0.5a | ||

| Normal | 3 | 1 | ||

| Abnormal | 26 | 15 | ||

| Alanine amino transferase (IU/L) | 5 - 40 | 0.4a | ||

| Normal | 6 | 2 | ||

| Abnormal | 23 | 14 | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 180 - 1200 | 0.4a | ||

| Normal | 22 | 13 | ||

| Abnormal | 7 | 3 | ||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 - 5.5 | 0.7a | ||

| Normal | 27 | 15 | ||

| Abnormal | 2 | 1 | ||

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6 - 8 | 0.6a | ||

| Normal | 23 | 13 | ||

| Abnormal | 6 | 3 | ||

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.2 - 1.2 | 0.2a | ||

| Normal | 11 | 4 | ||

| Abnormal | 18 | 12 | ||

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0 - 0.4 | 0.2a | ||

| Normal | 11 | 4 | ||

| Abnormal | 18 | 12 | ||

aFisher exact test.

5. Discussion

HE is a significant complication in patients with hepatic disorders. This phenomenon may complicate the course of acute hepatitis in a considerable ratio of patients (11). In our study, we assessed EEG patterns in children with HAV infection without any sign of HE. Actually, HE is a relatively uncommon feature in HAV infection. In a previous study, Sharma et al., reported an incidence of 25% for minimal HE in young-adult patients with acute viral hepatitis (19). From the 20 patients enrolled in the recent study, two of them had an acute HAV infection, two had HEV, while 16 had been diagnosed with HBV infection (19). In a study in Japan on 164 patients with acute hepatitis, 27 individuals were diagnosed with HAV infection, from whom, two (7.4%) cases developed HE during the course of the disease (11).

Abnormal EEG was recorded in 16/45 (35.6%) of our patients. These abnormalities included irregular spikes along with alpha (13 out of 16, 81.2%), triphasic (2 out of 16, 12.5%), and delta (1 out of 16, 6.3%) waves. To our knowledge, this is the first report on EEG alternations in HAV infected children without overt HE. In these conditions, abnormal EEG patterns may precede minimal and subsequently overt HE. EEG abnormalities have been associated with neuropsychiatric status in patients with HE (18, 19). EEG pattern with high continuous low-frequency waves has been associated with temporary lesions at posterior splenium in an adult with HAV infection (20). Generally, substitution of normal alpha waves (8 - 12 Hz) with the slow 5 - 7 Hz theta waves and subsequently with 1 - 3 Hz delta waves denotes a progressive neurological impairment. On the other hand, triphasic waves can be seen at the late theta wave activity (16).

We found no significant association between EEG patterns and demographic or clinical parameters (i.e. AST, ALT, serum protein and albumin levels). However, patients with irregular EEG patterns were significantly older (89.6 ± 35.2 months) than the patients with normal EEG (60.7 ± 36.2 months, P = 0.01). In previous reports, major risk factors for HE have been described as higher age, higher total bilirubin, prolonged PT, and non-A-E viral etiologies of hepatitis (11). Likewise, age and disease severity have been associated with EEG abnormalities in HCV infected patients (21, 22). In line with our observation, no associations were detected between HE development and AST, ALT, and serum albumin levels, as well as WBC and platelet counts in the study of Takikawa et al. (11). Neurological function in viral hepatitis can be influenced by the clinical phase of the viral disease as lower neuro-psychological and cognitive functions have been reported in patients in non-icteric (19) and fibrotic (23) phases.

The risk of HE can be modified by some extrahepatic factors as well. Decreased cerebral neurotransmitter function may contribute to the development of neurological symptoms and HE in patients with viral hepatitis (24). Risk of HE may be further manipulated by nutritional factors as daily protein absorption has been negatively associated with HE progression in patients with alcoholic hepatitis (25). Cerebral dysfunction in hepatitis can be attributed to the high circulating levels of neurotoxic substances resulted from hepatocytes degradation (2, 4). From these toxicants, a special role has been dedicated to the high levels of circulating ammonium (19). Furthermore, HE development is suggested to be related to impaired connectivity between various brain regions (26). Roles have been proposed for inflammatory cytokines; IL-1, TNF-a, and IL-6 (6, 27), concomitant Helicobacter pylori infection (28), hyponatremia (7), and high serum hyaluronic acid levels (29) as factors triggering the development and progression of HE.

As many patients are asymptomatic, the diagnosis of subclinical HE, as a potentially debilitating condition, may be masked in children with HAV infection. In these cases, detecting some degrees of cerebral irregular function can help physicians to detect those patients at risk of overt HE. Abnormal EEG patterns even in the absence of overt HE are of crucial importance as they may herald clinical encephalopathy.