1. Introduction

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a malformation found in 1 in every 2500 - 4000 newborns (1), with a survival rate of 70% - 90% (2). It is characterized by incomplete formation of diaphragm causing defects allowing herniation of abdominal contents into the chest (3). This mass-like effect prevents the lungs development. Clinically, according to the severity of pulmonary hypoplasia, the range of this abnormality can vary from an asymptomatic case to severe respiratory or gastrointestinal symptoms with unstable hemodynamics. These conditions are managed by surgery interventions including invasive methods or minimally invasive strategies (MIS) like laparoscopy and thoracoscopy (4-8). However, recurrence might occur as an unpredictable complication after a complete initial repair (9). In this paper, a case of a successful management of a re-herniated CDH is described. Considering that it is not a common abnormality and recurrence cases are even rarer, it seems worthy to report.

2. Case Presentation

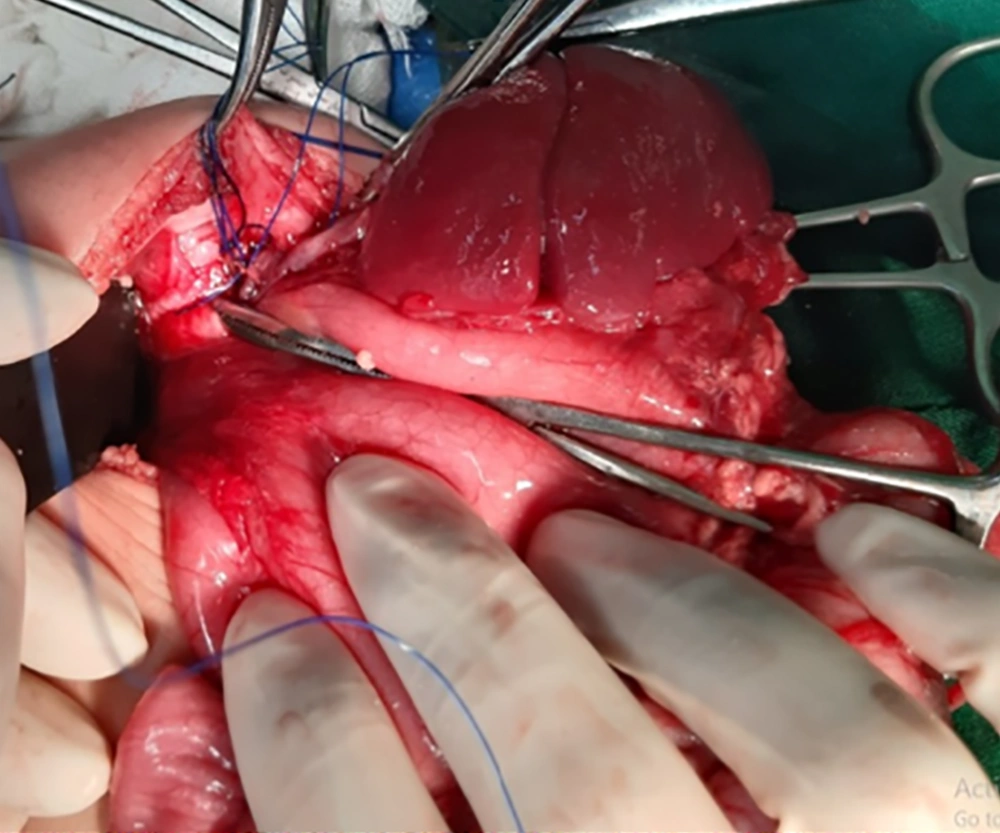

In this case report, a three-month infant with a history of laparoscopic CDH repair at birth, with recurrence, is presented. After a successful surgery, he was discharged in a good health status. He had a normal life and development during the three months. However, he suddenly began agitation, poor nutrition, and crying with no specific reason. He was visited by a pediatrics physician administrating just Pedilok syrup. His conditions got worse; fever, vomiting, diarrhea, and dyspnea were over imposed to his symptoms. In the next visit, the diagnosis was a simple viral gastroenteritis. However, on the third day, he developed severe dyspnea with a scaphoid chest and was then immediately admitted at the pediatric hospital. Imaging evaluations confirmed the clinical findings supporting the recurrence of CHD (Figure 1) and an emergency operation was planned. At the time of admission, the three-month infant weighting 6 kg presented with respiratory rate 65/min, oxygen saturation (SPO2) on room 85%-88% improved to 90% - 92% with four liters oxygen. Firstly, the standard monitoring and initial hydration were performed and he was pre-oxygenated with 100% oxygen for three minutes. Intravenous atropine 0.02 mg/kg and fentanyl 2 µg/kg was administrated as premedication. Sevoflurane was started with 2% and increased to 4% and after receiving atracurium 0.5 mg/kg as the muscle relaxant; he was intubated with an un-cuffed four mm endotracheal tube and underwent ventilator support. Ventilator settings were 15-Hz frequency with peak inspiratory pressures (PIP) kept below 24 mmHg, positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) at 3 - 5 Cm H2O and 55% FiO2. The proper insertion site was confirmed by checking bilateral equal air entry. Sevoflurane 2% with oxygen were as anesthesia maintenance. In spite of being aware from the potential risks of general anesthetic agents neurotoxicity in infants exception α2 agonists and opioids, we could not avoid them due to the type of surgery requiring deep anesthesia with a proper muscle relaxation (10, 11). After confirming the proper depth of anesthesia, he underwent a laparotomy through a transverse left upper quadrant incision (Figure 2). The defect was repaired under direct vision with interrupted sutures. At the end of the surgery before complete closure of the defect a chest tube number 18 was inserted. At the end of the surgery, the effects of muscle relaxant were reversed by neostigmine 0.04 mg/kg and atropine 0.02 mg/kg and then a good respiratory effort started. Surgery was completed with no adverse event and he was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and after 48 hours we planned for extubation. Fortunately it was well tolerated and he had an uneventful post extubation period. He was discharged with optimal conditions after 12 days (Figure 3). We followed him via telephone contacts for six months and fortunately no unexpected event was reported by his parents. We strongly believed that reporting this case could help the families with the similar conditions and awaring physicians from the threatening consequences of completely assuring the patients and the families. Therefore we clarified the importance of the issue to the parents and they permitted us to broadcast this case.

3. Discussion

The major causes of CDH mortality is pulmonary hypoplasia and severe pulmonary hypertension.

This is due to the hypo-plastic lungs of the neonate cannot, effectively excrete CO2, during the CDH repair (12). Additionally, gas insufflation results in raised intra-cavity pressure and the risk of barotrauma (13). CDH surgical repair is still challenging conditions, which are performed traditionally or by MIS. Each approach has some advantages and disadvantages. While open surgery is associated with musculoskeletal deformities in future, physiological, and respiratory complications; MIS provides less risk of adhesions but higher risk of recurrence, longer operation time, and difficult visualization (14). Lansdale et al., 2010, in a meta-analysis reported that MIS methods had greater risk of re-herniation (12). Considering suturing in a limited space of the neonate hemi thorax, restricted movements of native diaphragmatic tissue and less substantial tissue involved in suture and patches, recurrence following this surgical method could be anticipated (9). In another research, 3067 neonates were followed up after CDH repair and it was revealed that MIS were independently associated with higher risk of recurrence (15). Studies have emphasized that the influencing factors for re-herniation are not well known yet. Obviously surgeon’s technique and experience are important (16). In a cohort study conducted by Putnam et al. (17), a total of 3332 neonates with the history of CDH repair were followed up. They reported that 2.3% of the cases with the median age of 78 (28 - 112) days experienced recurrence and MIS methods, larger defect, liver herniation, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) were associated with the higher risk of re-herniation (17). In these cases anesthesiologists are also faced by a number of difficulties such as pulmonary hypoplasia, complications of mask ventilation due to the fear of high volumes, and the proper decision for extubation (1). Furthermore, parents should be well informed about the risks and benefits of two surgical methods. In this case, the surgeon had discharged the neonate in a healthy status and had tried to eliminate all parents’ fear and anxieties, thus, when his conditions were changed and even when he deteriorated more and more, they did not feel that informing the doctors from the mentioned operation might be so crucial. Obviously poor physical exam and medical history obtaining could not be ignored. The whole re-herniation status requires an early diagnosis and urgent intervention. To achieve the goal, informing the parents clearly about the potential risks of recurrence after a successful surgical repair and even a complete healthy status is vital. Spending enough time for the patient performing an exact physical exam and obtaining a complete medical history is strongly recommended. Finally to minimize perioperative morbidity and mortality a constant communication between the surgeon and anesthesiologist is crucial.