1. Context

Aging is associated with the development of various cardiovascular disorders, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension and heart failure. Every decade of aging affects the integrity of the cardiovascular system even in the absence of pathological factors. These changes in cardiovascular physiology due to aging are different from pathology, which also increases during aging (1, 2). Evidence suggests that the aging process significantly affects the structure and function of the cardiovascular system, as the middle age and old age are followed by changes in the heart muscle. Variations in the functioning of the cardiomyocytes are central factors in aging-dependent changes, because they play an important role in cardiovascular hemodynamics. Aging influences the functioning of the cardiomyocytes at different levels, so that aging has a direct impact on calcium homeostasis, cardiac muscle contraction, and paired stimulation of contractile and cellular integrity of cardiomyocyte organelles (3, 4). These factors are necessary in the neohumoral regulation of cardiomyocyte function through adrenergic and renin-angiotensin systems (5-9). In addition, middle age and old age cause changes in the components and quality of extracellular matrices, affecting not only the structures of the cardiomyocytes, but also the cardiac function (10, 11). Cardiac hypertrophy is one of the key variations in the cardiac structure linked to aging that is caused by various underlying factors (12).

2. Effects of Aging on the Heart

The calendar age is a process dependent on time. For this reason, middle age and old age are considered to be in line with the increase in mortality, although the calendar age is not regarded to be a factor indicating an individual’s health. On the contrary, biological age is used as one of the measures of human health assessment. The term “functional aging” or “functional middle age” is defined by emphasizing intrinsic constraints in describing an individual’s health while taking into account the calendar age. This principle is based on whatever that humans can do in relation to others in society; however, it may be expanded to include indicators, such as the level of functional abilities maintained by tissues and organs in older ages. Finally, the concept of “successful middle age and successful aging” represents the process resulting from the balance between winning and losing (12, 13).

Based on this concept, the structural and functional changes of the heart that occur with aging in healthy people can be interpreted as a type of adaptation to vascular changes occurring during middle age. Middle age results in processes such as vascular stiffness and increased systolic pressure in vessels that together with increased peripheral vascular resistance can lead to aortic dilatation and vessel wall thickness. This, in turn, causes an increase in the ventricular wall thickness, the death of myocytes and the deposition of collagen (14, 15). At rest, the cardiac pump function remains constant through prolonged contractions, but this prevents complete myocardial rest and causes a decrease in the initial ventricular filling rate. The cardiac implants over-regulate to compensate for abnormal filling and prevent diminished end-diastolic volume, including enlargement of the left atrium and an increase in the participation of the atrium in the ventricular filling (14).

In sum, these adaptations are established in response to reduced heart storage due to middle age. The changes in cardiovascular storage are inadequate to create clinical heart failure, but these factors also affect the signs, symptoms, severity, and prognosis of heart failure that can be caused by any reason. The heart of a middle-aged or elderly person has a greater sensitivity to harmful effects and external factors, including increased vascular afterload and disproportionate arterial-ventricular load, as well as internal factors, including a reduction in cardiomyocyte contraction and decreased ability of the cardiomyocytes to respond to stress (16).

3. Cardiac Hypertrophy

The mammalian cardiomyocytes are generally withdrawn from the cell cycle shortly after birth. Therefore, cardiomyocytes are often found during the late stage of differentiation during middle age and do not proliferate under physiological conditions. The heart tissues show the flexibility that can empower the heart; under these conditions, it responds to environmental requirements, and the cells can grow or shrink and be destroyed through exposure to pathological and physiological stresses. Cardiac hypertrophy is subdivided into the physiological type that accompanies increased normal cardiac function and the pathological type associated with heart failure (17).

The increase in normal cardiac output mainly occurs through hypertrophy of the cardiomyocytes in response to body enlargement or exercise training. The enlarged cardiomyocytes receive adequate nutrition through the expansion of the capillary network, but abnormal cardiac functional and structural enlargement do not occur in this way. For this reason, physiological hypertrophy generally is not considered to be a risk factor for heart failure. In contrast, pathological hypertrophy is associated with the production of high levels of neurohumoral mediators, hemodynamic overload, damage, and loss of cardiomyocytes. In pathological regulation, the growth of cardiomyocytes exceeds the capacity of capillaries to supply nutrition and oxygen, leading to cardiac hypoxia and pathological remodeling in rodents (18, 19). Since cardiac hypertrophy plays a pivotal role in cardiac remodeling and is an independent factor for cardiac events, it is very important to understand this process. Previous studies have indicated that heart failure is associated with a complex range of pathological changes, including capillary expansion, metabolic disorders, sarcomeric irregularities, changes in calcium transport, inflammation, cellular aging, cell death and fibrosis. There is also some overlap between the mechanisms of physiological and pathological hypertrophies (17).

Accordingly, heart failure can be categorized into two types: heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). HFrEF is developed through the accumulation of myocardial damages and the upward trend of losing cardiomyocytes, and it occurs typically in response to myocardial infarction, hypertension or cardiomyopathy. Furthermore, the oxidative stress present within the cardiomyocytes induces cardiomyocyte death and replacement fibrosis (20, 21). Losing the cardiomyocytes causes increased changes in the extracellular matrix and participation in left ventricular dilatation and left ventricular eccentric remodeling (22).

It is estimated that 50% of patients with heart disease have HFpEF. In addition, concentric remodeling and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction can also be seen in these individuals. Obese or overweight people with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic pulmonary disease, anemia and chronic kidney diseases may experience systemic inflammation; these systemic diseases increase the risk of HFpEF. The HFpEF structural changes are detectable through the hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes, interstitial fibrosis, and functional changes (23-26). Replacement fibrosis does not usually develop in HfpEF because cell death is not predictably increased in the HFpEF (27).

3.1. Types of Cardiac Hypertrophy

The heart has the ability to respond to environmental conditions and it is able to grow or shrink. Depending on the strength and duration of stimulation, the heart size can increase, which can be categorized into two types of hypertrophy: pathological and physiological. The physiological hypertrophy is characterized by normal or incremental levels in contractile function and the normal organization of the heart structure (28). The pathological hypertrophy is also associated with increased cell death and fibrosis remodeling and can be detected by reductions in systolic and diastolic functions, which often lead to heart failure. The stimuli result in various cellular responses, including gene expression, protein synthesis, sarcomeric accumulation, cell metabolism and developed cardiac hypertrophy (29-31).

The collected documents suggest differences in pathological and physiological hypertrophies in terms of signaling pathways. Additionally, the pathological cardiac hypertrophy, especially in the left ventricle, has short-term benefits and long-term risks although the mechanism regulating this transition from compatibility to hypertrophic abnormality has not yet been specified (32).

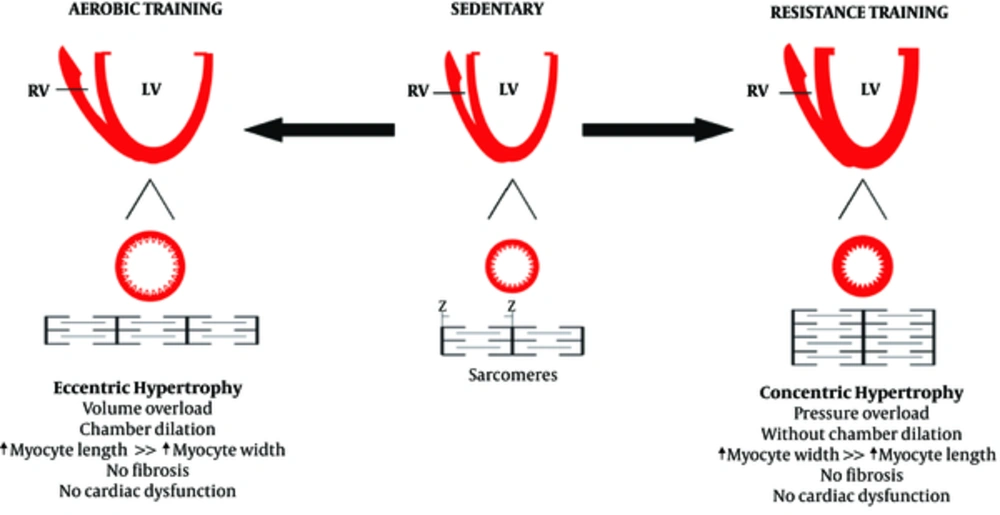

According to heart geometry, cardiac hypertrophy is subjected to different types, including eccentric and concentric. Eccentric hypertrophy is developed by volume overload and non-pathological eccentric hypertrophy that is characterized by an increase in ventricular volume, wall and septal thickness. Pathological eccentric hypertrophy commonly develops after heart diseases, such as myocardial infarction and dilated cardiomyopathy, resulting in the dilatation of ventricles and the elongation of cardiomyocytes. Concentric hypertrophy is associated with an increase in the wall and septal thickness and a decrease in the left ventricular dimensions (24, 33, 34). The cardiomyocytes usually increase in thickness more than in length; this develops under pathological conditions such as high blood pressure and vascular disease, although some regulators, like wrestling, cause induction of non-pathological eccentric hypertrophy (35)

3.2. Pathological Concentric and Eccentric Hypertrophies

Left ventricular concentric hypertrophy occurs due to diseases such as hypertension (even without a specific disease), which enhance the risk of cardiovascular progression with high-risk levels of death from cardiovascular disease (35, 36). In accordance with the evidence, some degree of stress in the ventricular end-diastolic wall acts as a signal regulating hypertrophy. This can lead to a greater induction of left ventricular concentric hypertrophy in patients with hypertension and low levels of ventricular end-diastolic wall pressure, which are characterized by a significant increase in the relative wall thickness (37, 38). The cardiomyocytes existing in myocardial concentric remodeling that have excessive thickness show an increase in diameters, but have no significant elevation in length, significantly reducing the mean length to width (L/W) ratio (37). This phenomenon occurs because of the orientation in the contractile sarcomeric units that add to the cardiomyocytes.

In a heart that has afterload pressure, the sarcomeres are added in parallel, which shows how they change the L/W ratio (39, 40). This process is evident as the muscle wall enlargement remains unchanged in the dimensions of the ventricular chambers although the dimensions of the posterior left ventricular wall are significantly increased during systolic and diastolic periods. Therefore, the common consequence associated with concentric hypertrophy is increased ventricular diastolic stiffness, which causes cardiac dysfunction (41).

Pathological cardiac growth, especially eccentric hypertrophy, is caused by an increase in preload, including valve failure or increased volume overload (37). In rats with myocardial infarction, 77% of the animals with eccentric cardiac remodeling suffered from systolic dysfunction. Comparing the length and width of the cardiomyocytes showed that the L/W ratio was unchanged, as in a normal heart. This is due to the thickness and length of the cells. The mechanism of this total increase in size is due to the parallel addition of sarcomeres in a row and in response to an increase in volume overloads (37). In addition, when evaluating specific left ventricular parameters, the researchers found that the internal diameter was increased in rats with increased volume overload while the interventricular septum or the dimensions of the posterior left ventricular wall had no changes (42).

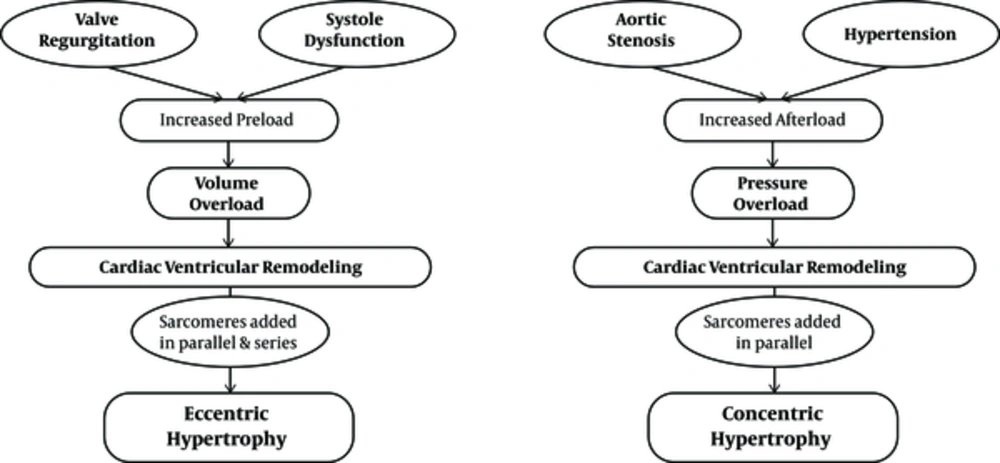

It is clear that middle-aged or old-aged people who live a sedentary life are somehow faced with pathological concentric hypertrophy. Existing evidence also suggests that underlying diseases in these individuals, including hypertension, vascular wall stiffness, and other diseases, can cause concentric hypertrophy (43) (Figure 1).

Pathological eccentric and concentric hypertrophy (43)

3.3. Middle-Aged Effect on Cardiac Responses to Exercise Training

Exercise training imposes physiological stress on the body, which requires responses coordinated by the cardiovascular, respiratory and nervous systems to increase blood flow and supply oxygen for the skeletal muscles. At rest, the muscles account for approximately 20% of the total blood flow, but this can be increased up to 80% during exercise training. Therefore, dysfunction in one of these systems can lead to a significant decrease in the maximum cardiac output during total exercise training (44).

It is well-defined that heart involvement contributes to increased cardiac output in response to the high metabolic requirements of exercise training and this is essentially dependent on the dynamic regulations of two physiological parameters, namely, heart rate (HR) and stroke volume (SV). In healthy adults, the adrenergic stimulation caused by exercise training rapidly increases heart rate and stroke volume. The stroke volume increases primarily by increasing myocardial contractions and reducing the peripheral vascular resistance. Elevated stroke volume increases by up to 40–50% of the maximum capacity corresponding to the intensity of exercise training, then reaches a plateau, and further reinforcement in output proceeds proportional to the increase in heart rate (45).

While older adults can still increase their cardiac output in response to exercise training, the relative increase is usually reduced compared with younger people. The decrease in maximum heart rate, also known as chronotropic incompetence or disorder, is the main factor in reducing cardiac response to exercise training in adults. Natural aging results in a progressive decrease in the maximum heart rate of about 0.7 beats/minute/year (46). Although the mechanism of this chronotropic incompetence has not yet been specified, degenerative changes in the transmission system associated with autonomic dysregulation may play a major role. Most importantly, the decrease in the peak HR due to middle age has a strong association with a reduction in exercise training capacity, and this is an independent predictor of cardiovascular events and mortality (47-49).

The impact of middle age and aging on the enhancement of SV via exercise training has not yet been clearly demonstrated. Generally, the heart of older adults still has the ability to increase SV in response to exercise training (albeit at insufficient levels of compensation in reducing peak beats). The mechanism by which heart SV can be increased by exercise training may be altered with the age of the individual. However, the increase in myocardial contractions is considered to be the main measure for increasing SV in the hearts of young people. Enhanced SV due to exercise training in the heart of older adults is mainly associated with the elevation in end-diastolic volume or a slight change in contractions (50).

In general, normal middle age significantly reduces both chronotropic and inotropic responses of the heart to exercise training. Clinically, this phenomenon refers to the storage disorders of the heart, which shows the inability of the heart to strengthen the cardiac output in response to the increased need for physiological stresses, possibly due to exercise training or specific medications (51). Concomitant with middle-age-induced changes in the mechanisms of peripheral oxygen delivery and consumption in skeletal muscle, inadequate oxygen transfer from impaired cardiac storage is a major factor in reducing functional capacity in adults, especially in patients with heart disease (52-56). Maximal oxygen consumption is the standard method of measuring exercise training capacity. During normal middle age, VO2 max is reduced down to about 10 per decade in active healthy people, but this decreases in people over 70 years and among people with heart disease it is more accelerated (9, 57). This process shows that the mechanism leading to storage disorders of the heart during middle age may be due to an increased risk of heart disease by age (Table 1) (51).

| CV Parameter at Park Exercise | Effects of Aging |

|---|---|

| Cardiac output | ↓ / NC |

| Heart rate | ↓ |

| LV stroke volume | ↑ / ↓ / NC |

| LV end-diastolic volume | ↑ |

| LV contractility | ↓ |

| Early diastolic filling rate | ↓ |

| VO2 max | ↓ |

| (A-V) O2 difference | ↓ |

Some Cardiovascular Changes in Middle Age (51)

3.4. Physiological Hypertrophy

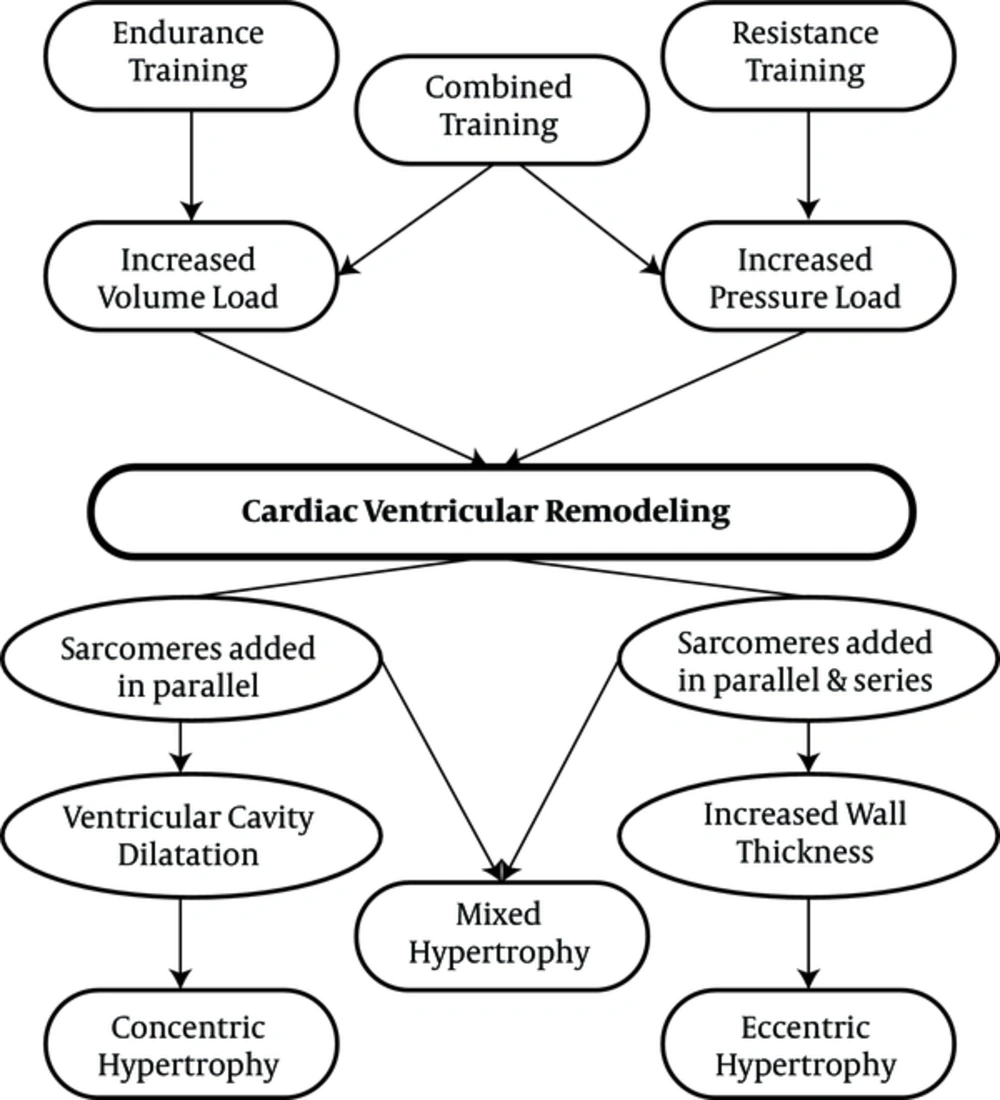

Similar to pathological hypertrophy, physiological hypertrophy is also a response of the heart to the strains caused by eccentric and concentric remodeling. Increased volume overload can mainly cause left ventricular dilatation, which can also be caused by endurance physical activities (58-60). Some researchers have demonstrated that the hearts of animals participating in endurance training was accompanied by the addition of new sarcomeres into a series of existing sarcomeres that previously had pathological cardiac hypertrophy (61). On the other hand, physiological concentric remodeling occurs due to increased pressure overload, which is caused by participating in resistance training programs. It is characterized by increasing myocardial volume and wall thickness without changing the size of the chambers (59, 60, 62). In resistance training programs, there is a significant increase in systolic blood pressure, and the sarcomeres are added in parallel to existing sarcomeres, increasing the thickness of the walls in a similar manner to pathological hypertrophy (63, 64). Interestingly, combined physical activities involving both pressure overload and volume overload, which have both aspects of endurance physical activities (running and swimming) along with resistance physical activities can lead to combined hypertrophy (65). Differences in the types of physiological stimuli can be observed in the differences in the types of hypertrophy. Right ventricular remodeling can also occur with endurance exercise training, although left ventricular dilation is caused by an increase in both systolic and diastolic functions (66).

The physiological cardiac remodeling in athletes is not associated with interstitial fibrosis, as occurs in pathological hypertrophy (67). In addition, a study found that exercise training prevents myocardial inflammation induced by isoproterenol injection (67). Moreover, exercise training can prevent myocardial deficiencies. It should be noted that inhibiting myocardial hypertrophy by exercise training could lead to lower NFkB expression (68). Physiological remodeling is a response to high exercise volume, reflecting the importance of exercise training in morphological changes in the heart60 (Figures 2 and 3).

Resistance, endurance and combination exercises and their effect on cardiac hypertrophy (43)

The effect of aerobic and resistance training on cardiac hypertrophy (69)

3.5. Effect of Exercise Training on Middle-Aged Hypertrophy

The distinctive concept of cardiac hypertrophy is particularly relevant to adult hearts. Contrary to findings in young animals, aerobic exercises generally cause some degree of cardiac hypertrophy (70). Studies based on exercise training of adults and older people have shown a wide variety of cardiac development in response to exercise training (71-76), with some studies indicating reversal of middle-aged hypertrophy through exercise training. One of these studies has evaluated the effect of exercise training on the growth of cardiomyocytes in the heart of adults. Kwak et al. trained young and adult rats at 75% VO2 max for 12 weeks. Their findings indicated that the training induced the hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes in young rats. These results were associated with a regression in the size of cardiomyocytes (69% reduction in cross-sectional surface area) in adult samples (74). Alternatively, in another study, training on a treadmill or with swimming at low to moderate intensity in adult Wistar rats did not affect the size of the cardiomyocytes. Differences in training periods and age of animal samples may result in different findings. In addition, only a small number of studies investigated the decrease in blood pressure via exercise training in adult animal specimens (75, 77).

It is not surprising that the molecular basis for the different potential effects of growth due to exercise training in adult heart samples is not well defined. Obviously, the cytoprotective effects of exercise training may improve the survival of adult hearts. Therefore, stimuli for active pathological hypertrophy are reduced. In fact, trained adult rat hearts showed a decrease in several apoptotic indexes, which usually rises in the hearts of adults. However, it has not been completely determined as to what the mechanisms of these changes induced by exercise training are, including decreased translation of factors for cell death and inhibiting pathological growth stimuli in the heart of older adults (74, 76, 78).

The signaling mechanism of exercise training, which potentially improves the cardiomyocytes in adults, might be related to cardioprotective effects of the IGF1/PI3K/Akt pathway. Increasing expression of cardiac IGF1, PI3K and Akt1 is indicative of improved survival of cardiomyocytes in adult rats exposed to ischemic damages (28, 36, 79). More importantly, several studies have shown that similar to young animal specimens, aerobic exercise training causes increased Akt phosphorylation in the heart of adult and old rats, although its level is low (77, 78, 80). Although low levels of Akt activity in the heart of trained rats is sufficient to increase cell survival and decrease pathological growth, it is not enough to develop physiological growth (51). Finally, the variation in cardiac growth responses to exercise training among young and adult animals is probably related to fundamental differences in the substrates between the young and the adults and the pathological hypertrophy pathways and apoptosis. Indeed, when young and adult rats participated in the same 12-week training, it was found that the levels of MAPK and calcineurin/NFAT signaling were decreased in the hearts of adults and did not change in the hearts of the youth, or the changes were not significant, although Akt was increased in both groups (78, 80). In this regard, some studies have shown that Akt causes inhibition of MAPK pathways that participate in the development of hypertrophy (81).

Although the role of exercise training through other mechanisms has been less considered, including changes in anti-aging hormones and oxidative stress, MAPKs may be involved in the hypertrophy of the middle-aged heart. In this context, it has also been reported that exercise training can be effective in improving age-related mitochondrial disorders (82, 83).

4. Conclusions

According to these findings, middle age along with physical inactivity seems to be associated with pathological hypertrophy, during which the intraventricular volume decreases and the heart wall thickness increases. However, exercise training through various mechanisms creates the possibility of driving pathological hypertrophy towards physiological hypertrophy. In addition, the type and duration of the exercise training can influence the respective effects.