1. Background

Leishmaniasis is listed by the World Health Organization (WHO) among the most important tropical diseases, with 350 million people at risk in 89 countries, between 12 and 15 million people infected, and 1.5 to 2 million new cases each year (1). Leishmaniasis began by obligating the Leishmania genus' intracellular parasites and manifested in three primary clinical forms in humans: Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, and Visceral leishmaniasis (2).

Leishmania major (L. major) is marked as an etiologic agent of CL, especially in Pakistan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Iran (3). In Iran, CL is the most common vector-borne disease after malaria, with about 20,000 new cases reported annually (4). For over half a century, chemotherapy based on pentavalent antimonial has constituted the primary treatment for CL in most countries. Second-line drugs, such as amphotericin B, pentamidine isethionate, miltefosine, and paromomycin, have also been used to treat this disease (5). However, these compounds have been undermined by drug resistance, considerable toxicity, variable efficacy between strains and species, and the required long-course administration (6). Another major challenge is co-infection with the human immune/deficiency virus (HIV) because there is no effective therapy for afflicted patients (7). For all these reasons, the need to find new active antileishmanial compounds is urgent. Recently, interest in medicinal plants in treating these infections has been growing (8).

Xanthium strumarium (X. strumarium) L. (Asteraceae) is an herbaceous annual plant widely used in traditional herbal medicine to treat trypanosomiasis (9), malaria fever (10), bacterial infections, diabetes, skin pruritus, inflammatory diseases like rhinitis and rheumatoid arthritis (11), and skin sores such as leishmaniasis (12). The biological activities of X. strumarium are attributed mainly to the presence of an essential class of phenolics (especially terpenoids) called sesquiterpene lactones (STLs). The phenolics can be grouped according to their carboxylic skeletons into such active metabolites as xanthatin, xanthinin, and 8-epixanthatin, displaying significant antimicrobial, antifungal, and antitumor activities (13).

Metabolomics is a branch of ‘omics’ research involving the study of global metabolite profiles in biological systems under given sets of conditions (14). Metabolomics is applied as a precise and noninvasive tool in diverse areas, including disease diagnosis, biomarker discovery, drug development, microbiology, and the identification of novel drug targets (15, 16).

2. Objectives

In the current study, the inhibitory effects of the leaf extract of X. strumarium on the intracellular stage of L. major were investigated. Nuclear magnetic resonance (1HNMR) spectroscopy analysis was used to determine the metabolome pattern alternations. Besides, we elucidated any inhibitory effect that the extract may have on the amastigote’s metabolome profile stage of L. major.

3. Methods

3.1. Plant Material

Xanthium strumarium leaves were collected from Kermanshah Province, Iran, during the maturing season (July-September 2017). A voucher specimen was deposited in the central herbarium of Tehran University, Tehran, under voucher specimen number 48241.

3.2. Preparation of Crude Plant Extracts

The dried powdered leaves of X. strumarium (40 g) were macerated with an ethanol / water mixture (5:1) for three days at room temperature and then filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure at 45°C to afford the light-green extract. All the extract was mixed with active charcoal, centrifuged to isolate plant pigments, and kept at -20°C until required for biological testing and phytochemical screening (17).

3.3. Determination of Total Polyphenol Contents

The extract’s total phenolic content was determined as per the method of Scherer and Godoy (18) in triplicate. The total phenolic content was calculated according to a calibration curve.

3.4. Cell Culture

Leishmania major promastigotes (MRHO/IR/75/ER) isolated firstly from infected BALB/c mice were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 100 U/mL penicillin (all from Sigma, CA, USA) at 23°C - 26°C in a tissue flask (19).

3.5. Xanthium strumarium Extract Cytotoxicity to Macrophage

BALB/c mice macrophages were maintained in a tissue flask in RPMI1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 1% L-glutamine. The cytotoxicity test was carried out as described by Wang et al. (20). Briefly, the cell suspension was plated at a density of 8 × 103 cells/well in a 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Xanthium strumarium leaf extract compounds dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. The adhered macrophages were incubated in the absence or presence of various concentrations of X. strumarium extract (150 to 0.015 µg/mL). Amphotericin B and untreated cells were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The blank contained RPMI medium alone. After 48 h of incubation at 37°C, the viability of cells was determined by the MTT method. The absorbance was read for each well at 562 nm. Cell viability (%) was calculated at each concentration using the following formula:

Cell viability = (Average absorbance in duplicate drug wells - average blank wells)/(Average absorbance control wells - average blank wells) × 100

Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) were calculated using GraphPad Prism software.

3.6. Antiamastigotes Assay

BALB/c mice macrophages (5 × 104 cells/well) were allowed to adhere to a glass coverslip in 12-well plates for 24 h at 37°C in 5% CO2. Simultaneously, logarithmic-phase L. major promastigotes were cultured in complete RPMI medium for 5 - 6 days without adding fresh medium represented as stationary promastigotes. Adherent macrophages were then adjacent to stationary-phase L. major promastigotes at a parasite/cell ratio of 10:1. After 24 h, infected macrophages were treated with different concentrations of the plant extract. Amphotericin B was used as the standard. After three days, the coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed in methanol, and stained with 10% Giemsa solution. The percentage of infected macrophages was determined as infection rate (IR), and the survival percentage was obtained through multiplication index (MI) (21).

MI = (No of amastigotes in experimental culture/100 macrophages)/(No of amastigotes in control culture/100 macrophages) × 100

3.7. Sample Preparation for NMR Spectroscopy

Mice macrophages were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2, and the adherent macrophages were infected with stationary promastigotes at a parasite/cell ratio of 10:1. The infected cultures were incubated for 72 h in RPMI medium (control group) or treated with IC50 concentrations of the leaf extract (0.015 g.mL-1 leaf extract/5 × 104 parasites) obtained from the anti-amastigote assay as noted above. The drug and medium were replenished daily for three days. Then, the trypsinized cells (8 × 107 amastigotes/vial) were washed twice with PBS and centrifuged. Chilled 1.8 M perchloric acid was added to the cell suspension, vortexed, and sonicated. The supernatant’s pH was adjusted to 6.8 and kept on ice for 60 min to allow potassium perchlorate precipitation. The supernatant was lyophilized before NMR spectroscopy (21, 22).

3.8. 1HNMR Experiments

Metabolomics analyses were carried out as previously described by Sheedy (23). First, lyophilized powder samples from each group were resuspended in D2O containing trimethylsilyl propionate (1 mM) as an internal chemical shift standard (δ = 0 ppm) and imidazole (2 mM) as a pH indicator (δ = 5.50 to 8.80 ppm). Samples were analyzed with Bruker AV-500 NMR spectrometer operating at 500.13 MHz at 298 K. 1HNMR spectra were obtained using an excitation pulse of 10-µs, mixing time of 0.1 s, relaxation delay of 3.0 s, spectral width of 6009.6 Hz, and 3000 transients with standard 1D NOESY pulse sequence to suppress the residual water peak (23).

3.9. Data Analysis

1HNMR spectra were preprocessed using custom-written ProMatab (V.3.3) code in MATLAB (V.7.8.0.347) to convert a proper format for multivariant analysis. The spectra were segmented into 0.005-ppm chemical shift bins, and the spectral areas (4.7 ppm) containing residual water were excluded. Data normalization and Pareto scaling were performed before data classification. The chemometric method applied for the pattern recognition model was partial least square- discriminate analysis (PLS-DA), a supervised classification technique frequently used to identify significant bins between experimental groups (24). The human metabolome database (HMDB) and LeishCyc database were used to extract the metabolites corresponding to the spectral bins. MetaboAnalyst 3.0 (www.Metaboanalyst.ca) was also conducted to investigate metabolic pathways. SPSS was used to determine the P-values.

4. Results

4.1. Total Polyphenol Content

The extract was found to have significant antioxidant activity with a value of 150 ± 4 µg/mL.

4.2. Cytotoxicity of Extracts of Xanthium strumarium to Macrophages

The MIC and IC50 values of different concentrations presented variable cytotoxicity against these cells (Table 1). The X. strumarium stock extract (150 µg/mL) showed the highest cytotoxicity (96%), while cell cytotoxicity decreased with reduction in the stock extract concentration. However, lower concentrations (0.15 µg/mL) were shown not to be toxic on the macrophages cell line. Amphotericin B (150 µg/mL) as the positive control presented cell viability similar to the stock fraction. IC50 value was reported as 49%, equal to 0.15 µg/mL.

| Concentration, µg/mL | Xanthium strumarium, % | Positive Control, % |

|---|---|---|

| 150 (stock) | 96 | 98 |

| 1.5 | 81 | 72 |

| 0.15 | 51 | 47 |

| 0.018 | 26 | 20 |

| Negative control | 15 | 20 |

aAmphotericin B and untreated cells used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

4.3. In Vitro Activity of Xanthium strumarium Extract Against Leishmania major Amastigotes

Different concentrations of X. strumarium extract were tested for their efficacy against amastigotes in macrophages. Based on the results, a dose-dependent decrease in MI values can be seen (Table 2). The concentration of 0.15 µg/mL had almost the same MI value as Amphotericin B (0.15 µg/mL). It was determined that the concentration of 0.015 µg/mL with an infection rate of 51% and a multiplication index of 57%, and it could be considered for the final treatment of dense amastigotes cultures.

| Concentration, µg/mL | Infection Rate, % | Multiplication Rate, % |

|---|---|---|

| 0.15 | 13 | 14 |

| 0.075 | 24 | 27 |

| 0.037 | 43 | 37 |

| 0.015* | 51 | 57 |

| 0.0015 | 84 | 95 |

| Negative control | 88 | 100 |

| Positive control | 10 | 11 |

aAmphotericin B and untreated cells used as positive and negative controls, respectively; and *, inhibitory concentration

4.4. Effect of Xanthium strumarium Leaf Extract on Metabolome Profile

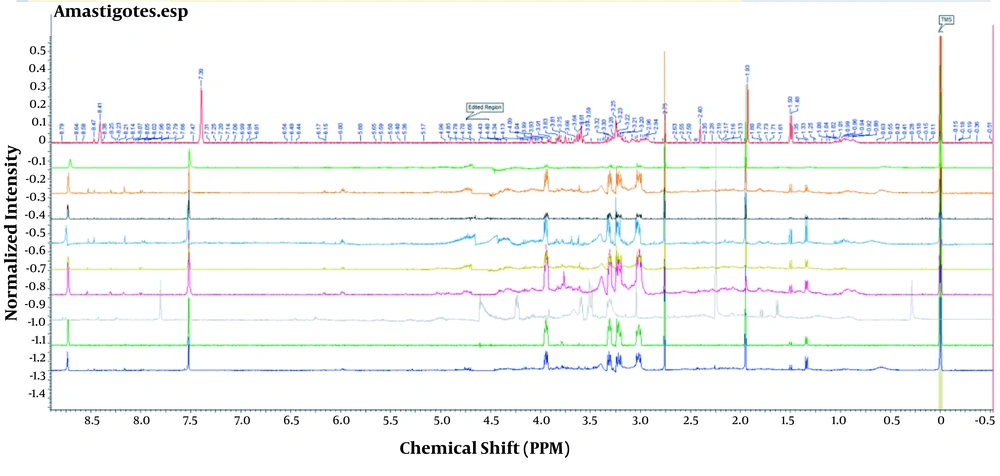

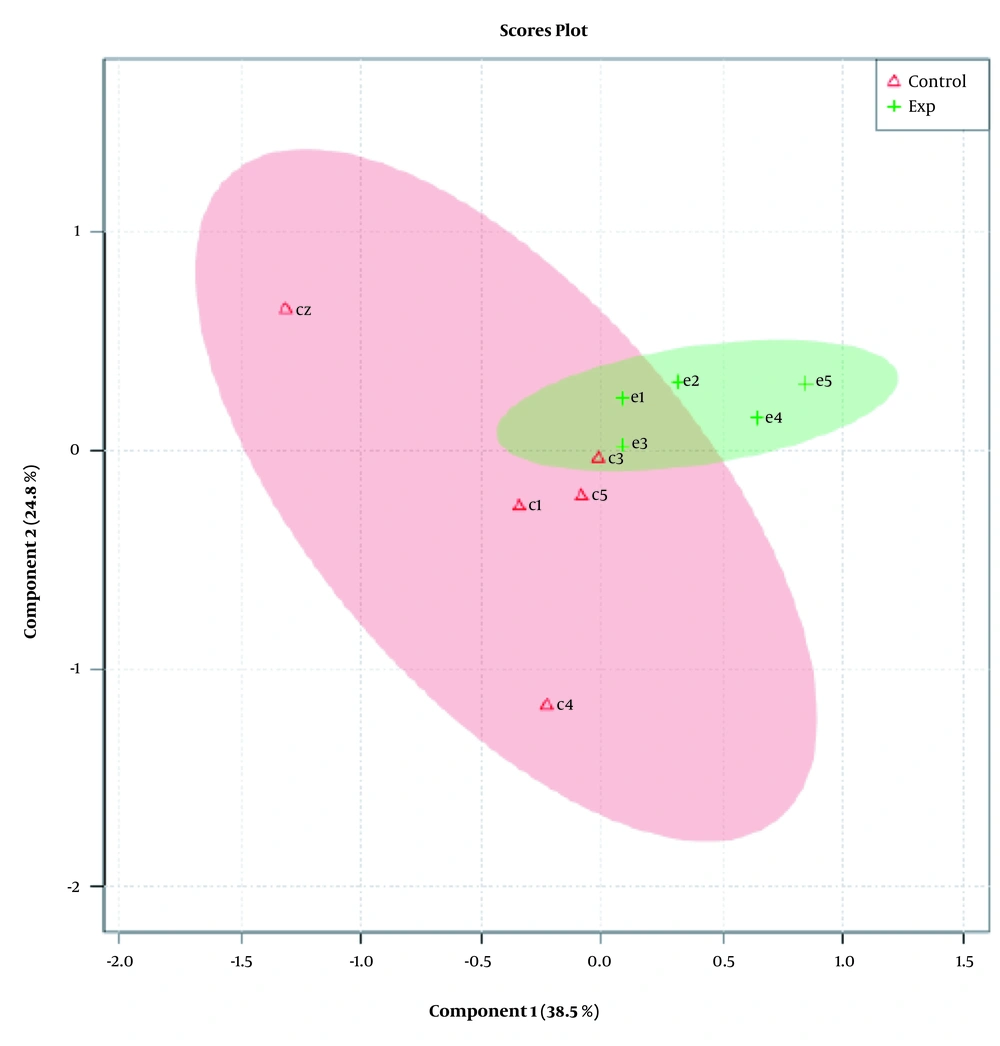

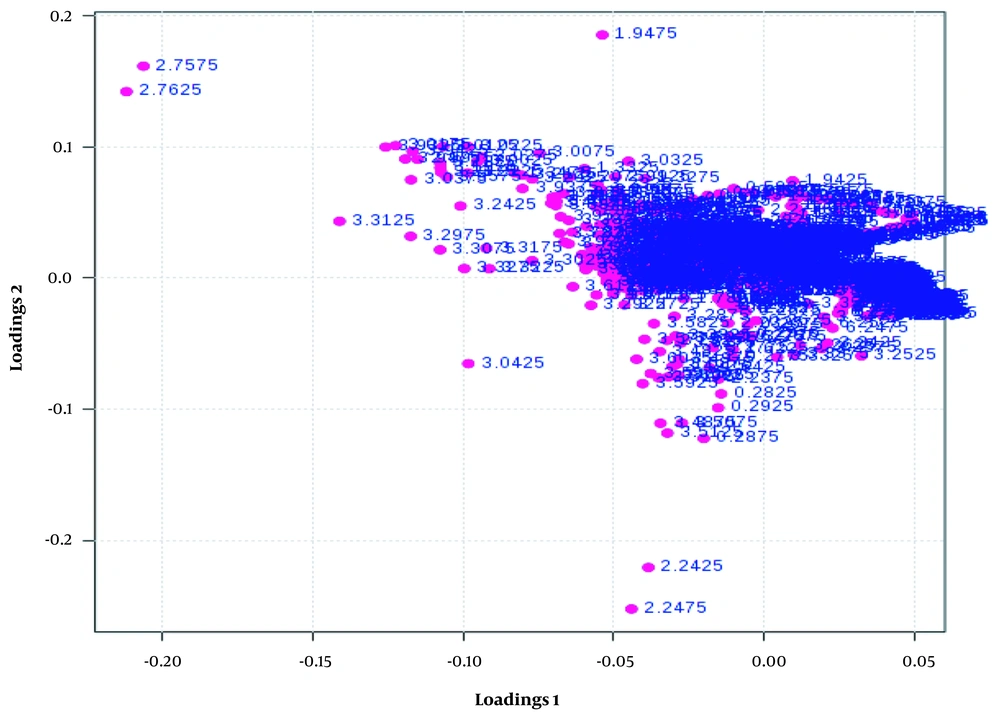

While Figure 1 depicts control and experimental NMR spectra’s, Figure 2 shows the score plot of PLS-DA modeling for the control and experimental groups. Red triangles indicate the control group, and green crosses are related to the experimental group. The loading plot is also used for outliers’ separation (Figure 3). Figure 3 indicates that the amastigote stage has affected metabolites as variable importance in projection (VIP) using PLS-DA analysis.

This plot indicates the relative contribution of bins/spectral variables to experimental and control groups’ clustering. Each dot in the figure demonstrates a bin. The loading [2] axis indicates the bin’s correlation towards the predictive variation shown in Figure 2. The loading [1] axis represents the magnitude of the spectral bins.

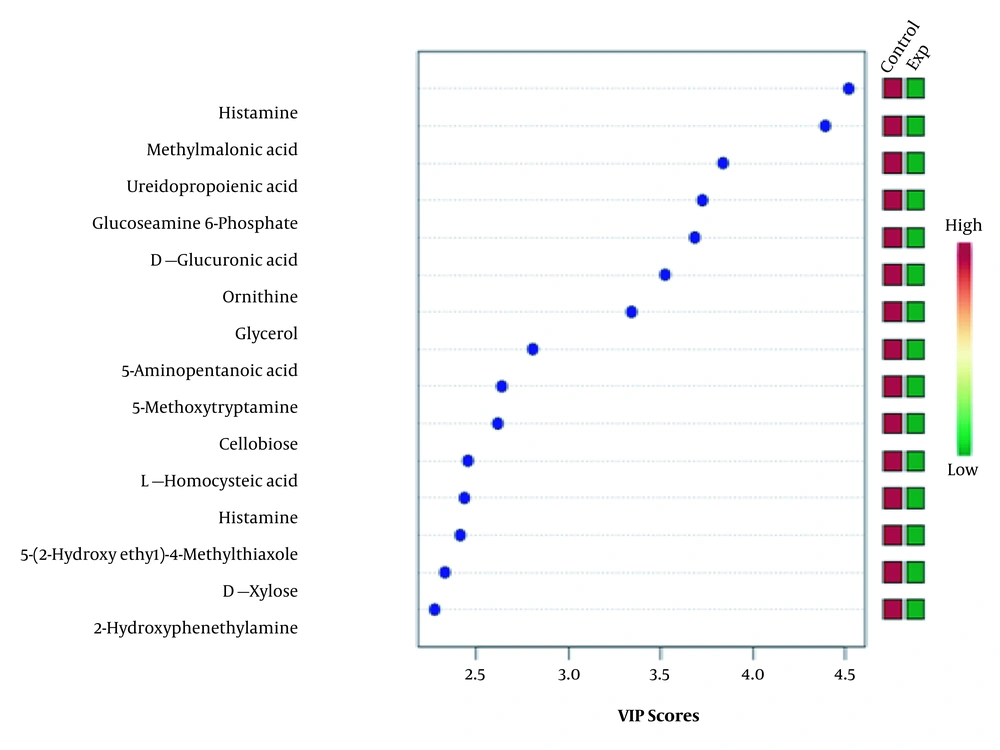

Variable important projection (VIP) is the measurement of the variable importance in the PLS-DA model, and the chemical shifts’ (metabolites) importance based on their variable score is shown in Figure 4.

The outlier metabolites correlating with the NMR spectra’s chemical shifts were identified by using the HMDB and LeishCyc reference databases. Also, generic databases, such as the KEGG pathway’s database and the MetaboAnalyst online pathway analysis, were applied to identify the affected metabolic pathways corresponding to these separated outliers (Table 3).

| Pathways | Metabolites Altered in Pathway | Total Metabolites in Pathway | Altered Metabolites in Pathway | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis | L-Valine; pantothenic acid; alpha ketoisovaleric Acid | 10 | 3 | 0.420 |

| Pentose and glucuronate interconversions | Glucose 1-phosphate; oxoglutaric acid | 6 | 2 | 0.423 |

| Valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis | alpha ketoisovaleric acid; L-valine | 6 | 2 | 0.423 |

| Galactose metabolism | Glucose 1-phosphate; uridine diphosphate galactose | 7 | 2 | 0.510 |

| Amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism | Glucose 1-phosphate; D-mannose; D-glucosamine 6-phosphate; N-acetyl-D-glucosamine-6-phosphate; uridine diphosphate galactose | 21 | 5 | 0.560 |

5. Discussion

In recent years, different strategies are employed in drug research in tropical diseases, of which the metabolomics-based approach represents a vital niche (25).

According to the acquired P-values, pantothenate and coenzyme A biosynthesis, pentose and glucuronate metabolism, valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis, galactose metabolism, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism are the most vital metabolic pathways affected by the plant extract as an antileishmanial agent. The present study’s results indicated the alternation of two metabolites, pantothenic acid and alpha-ketoisovaleric acid, in the pathway of pentanoate and coenzyme A (CoA) biosynthesis. Previous studies have revealed that pantothenic acid in trypanosomes plays a vital role in various cellular processes, such as the essential precursor for CoA biosynthesis. Enzymes containing phosphopantetheine prosthetic groups are involved in anabolic reactions such as fatty acid synthesis. Additionally, CoA is a fundamental cofactor for cell growth and is utilized in various metabolic reactions (26, 27), and the CoA biosynthesis pathway is used as CoA in different metabolic pathways of the amastigote stages. Therefore, it is possible that the leaf extract of X. strumarium, with a disruption in this metabolic pathway, results in parasite attenuation, which is consistent with the current results.

Pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) provides NADPH as a reductive agent in biosynthetic reactions and is required for protection against oxidative/nitrosative stress under in vivo conditions. Previous studies have indicated that reverse genetic blocking of the pathways providing NADPH and a potent uncompetitive inhibitor of the glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme of PPP in T. brucei resulted in a ~10-fold increase in susceptibility to H2O2 stress and, ultimately, cell death (28). Whitaker et al. (29) showed that the xylose kinase gene and the genes of xylulose reductase and ribulokinase are directly transmitted to the parasite through bacterial genes. Leishmania can rebuild a biochemical pathway that produces ribose 5-phosphate (ribulose-5P) from ribulose. Ribulose-5P is needed for glycolysis and de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis (29). The current results have also shown that glucose1-phosphate and oxoglutaric acid were altered in this pathway. Therefore, based on the results of the current and previous studies, it can be concluded that the extract of X. strumarium disrupts the two specific metabolites in this pathway, thus, interfering with the nucleic acid synthesis required for parasite proliferation, the sensitivity to oxidative stress, and cell metabolism (Krebs cycle) of the intracellular amastigotes. Leucine amino acid is efficiently used as the primary carbon source for de novo sterols biosynthesis (30). The utilization of intact leucine skeletons for sterol biosynthesis will significantly contribute to the Leishmania parasite’s metabolic economy.

Studies have shown that antifungal inhibitors of sterol biosynthesis cause growth retardation and death in several Leishmania and Trypanosoma species. Besides, one research has shown that lovastatin blocked promastigote growth and the incorporation of leucine into sterol biosynthesis (30). In the current investigation, it has been determined that two metabolites, namely alpha-ketoisovaleric acid and valine, have been changed in this pathway. The importance and role of these two metabolites have been discussed previously in this article. These two metabolites are also useful in the synthesis of acetyl coenzyme A required for the energetic pathways in the amastigote stage, including the Krebs cycle and fatty acid biosynthesis. Based on the current results, it can be assumed that any disturbance in this pathway’s metabolites can inhibit parasite growth by interfering with sterol biosynthesis and cellular energy.

Leishmania parasites synthesize various secreted and cell-surface glycoconjugates, facilitating their survival and development within the harsh environments they encounter (31, 32). Studies have shown that these phosphoglycans (PGs) play essential roles, such as facilitating oxidant resistance, inhibiting phagolysosomal fusion, and controlling the host’s signal transduction, in the infectious cycle of these protozoan parasites (33). Phosphoglycans are particularly rich in galactose (34), and numerous studies have indicated that deficient mutants in the formation of UDP-Galf or UDP-Gal transporter present an altered glycocalyx associated with parasite attenuation (33, 35, 36). Kleczka et al. (36) revealed that the deletion of β-Galf in phosphoglycan structures, glycoinositolphospholipids, and lipophosphoglycan was associated with the weakening pathogenicity of this parasite. Therefore, it can be assumed that X. strumarium leaf extract disrupts the galactose metabolism, impressing glycoconjugate biosynthesis as the cell surface coat, and finally, causes the attenuation of amastigotes due to increased susceptibility to host complement and oxidative stress.

In Leishmania, nucleotide sugars contribute to glycoconjugate biosynthesis, which plays an essential role in their survival, infectivity, and virulence (37). Previous studies have revealed that glycocalyx-deficient L. major mutants generated through the deletion of sugar nucleotides resulted in parasite attenuation. In L. major, mutation of the lipophosphoglycan gene is required to synthesize the LPG core domain, resulting in severe deficiencies in parasites’ ability to survive inside the sand-fly vector and to establish infection in mammalian macrophages (38, 39). In the present research, metabolites of N-acetylglucosamine 6-phosphate, glucose-1 phosphate, glucosamine-6 phosphate, mannose, and uridine diphosphate galactose diphosphate changed into amino sugar and a nucleotide sugar metabolic pathway. Therefore, based on the present results, it can be deduced that the leaf extract of X. strumarium influences these metabolites, disrupting the vital metabolic pathways of the parasite.

5.1. Conclusions

It can be concluded that X. strumarium leaf extract shows significant antileishmanial activity, and the affected metabolome pattern can be a charming candidate for the development of new drug targets against leishmaniasis. Further research is in progress to validate and determine the potential fractions of this plant’s leaf extract.