1. Background

Surfactants' structure consists of both hydrophilic and hydrophobic moieties that play an important role in drug delivery and many industries, including oil and petroleum, soap and detergent, energy generation, food and beverage, and environmental pollution remediation (1-5). Biosurfactants are new-age surfactants derived from plants, animals, and microbes (6, 7). They are equally diverse in structure and function and are gaining attention due to their biodegradability, stability in high salinity, acidity, and temperature, and they have lower critical micelle concentration (CMC) values than synthetic surfactants (6, 8, 9). Biosurfactants are divided into four main types: Glycolipids, lipopeptides, phospholipids, and polymers. Glycolipids and glycoproteins are produced by different strains of bacteria (8). The type of lipopeptide presents a heterogeneous class of biologically active peptides. Lipopeptides contain hydrocarbon chains or fatty acids that are hydrophobic and hydrophilic peptide chains typically produced by various bacteria, such as members of the Acinetobacter genus (10-12). The Acinetobacter genus has received more attention because it is widely used in the petroleum industry (13). Acinetobacter junii B6 was isolated from an Iran oil drilling site (11, 14). Investigations of A. junii B6 lipopeptide biosurfactant’s structure, physicochemical, and aggregation properties have been carried out, and the CMC was evaluated at about 300 mg/L (11).

Despite the numerous benefits of biosurfactants to many industries, the greatest limit to using them in many manufacturing processes is their high production cost. One of the efficient techniques to produce biosurfactants is through bioencapsulation (15, 16). The bioencapsulation of growing bacterial cells is attractive because it provides bio-transformational and biosynthetic abilities to produce diverse valuable products such as biosurfactants, antibiotics, enzymes, and organic acids (15, 17-20). Several advantages are provided by bioencapsulation for the production of biosurfactants, including the ability to separate cell mass from bulk liquid for reuse, ensuring continuous operation over an extended period, and increasing reactor productivity (15, 17, 19). Various natural and synthetic polymers have been used in bioencapsulation and drug delivery (21). The mild gelling, biocompatibility, and biodegradability of alginate make it popular in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Alginate has also been used to microencapsulate therapeutic agents for prolonged and controlled drug delivery (19, 22, 23). In addition to being simple, nontoxic, and inexpensive, entrapment in calcium alginate is also one of the most suitable methods for bioencapsulation (18). Hydrogels are a three-dimensional and crosslinked network of hydrophilic polymers. They can absorb a large amount of water or biological fluids, which leads to their swelling while maintaining their 3D structure without dissolving since calcium alginate hydrogels can be used instead of calcium alginate beads. Applying the statistical design of experiments to the immobilization method improves product yields, further validating the response to the desired product, which saves time and overall cost. Three steps of the design expert (randomization, replication, and blocking) are used to improve the efficiency of experimentation (24-26).

2. Objectives

The main aim of this study was to optimize the bioencapsulation of biosurfactant-producing A. junii B6 in calcium alginate hydrogel using the two-level factorial method and observing the effect of bioencapsulation in increasing microorganism's resistance to harsh conditions and biosurfactant production. Sodium alginate concentration, calcium chloride concentration, and hardening time were selected as factors, and surface tension was the main test design response. Since the amount of biosurfactant production indicates the number of encapsulated microorganism cells, the amount of biosurfactant production was used as an index for optimization (15).

3. Methods

3.1. Primary Culture of Acinetobacter junii B6

Acinetobacter junii B6 was isolated from an Iranian oil excavation site and characterized in our previous study (14). Primary cultures were prepared by transferring from prolonged-storage vials to a solid mineral salt medium containing one percent crude oil as the only carbon source and incubated at 37°C overnight (11).

3.2. Preparation of Bioencapsulation Beads of Acinetobacter junii B6

Sodium alginate solution and calcium chloride were prepared under sterile conditions and at different concentrations. A 1% (v/v) of a microbial suspension (OD600 = 0.8) was gently mixed with sodium alginate solution for one hour to obtain a homogeneous mixture. The resulting mixture was removed by a 10 mL sterile syringe with a 23 G stainless steel needle and sprayed dropwise at a distance of 5 cm into a stirred calcium chloride solution.

3.3. Surface Tension Measurements

The measurement of surface tension (at room temperature) was done by plate method according to Wilhelmy using a tensiometer (krüss® tensiometer k100) compared to the negative control (culture medium without bacteria). The device's surface tension reading accuracy was measured with absolute ethanol and distilled water before each reading (14). The beads, after preparation, are separated and washed and then added to the culture medium. The measurement of the surface tension of the supernatant culture medium (1500 rpm, 5 min) after equilibrium was investigated as a measure of biosurfactant production and the main response of the experimental design (15).

3.4. Optimization of Bioencapsulation

An experimental design of two factorial methods was used to identify the most important factors potentially affecting the bioencapsulation of A. junii B6 and the production of biosurfactants. The selected factors were sodium alginate concentration, calcium chloride concentration, and hardening time. The specified codes for each factor and its levels are presented in Table 1. According to the design of the experiment using the two-factor factorial method, 8 (23) experimental setups were designed and carried out using Design Expert 7.0.0 software. In subsequent steps, the two-factor interaction (2FI) model following the equation below was used to estimate the mathematical relationship between variables.

| Factor | Symbol | Unit | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Center | High | |||

| Alginate concentration | A | (%w/v) | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| CaCl2 concentration | B | (%w/v) | 1 | 2.5 | 4 |

| Hardening time | C | (min) | 15 | 20 | 25 |

The predicted response is y, the coded levels of the independent variables are represented as X, β0 is the model constant, βi is the linear coefficient, and βij is the cross-product coefficient.

Moreover, to ensure the accuracy of the results, the center point was repeated three times, and the results were compared. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out on the obtained results.

3.5. Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis

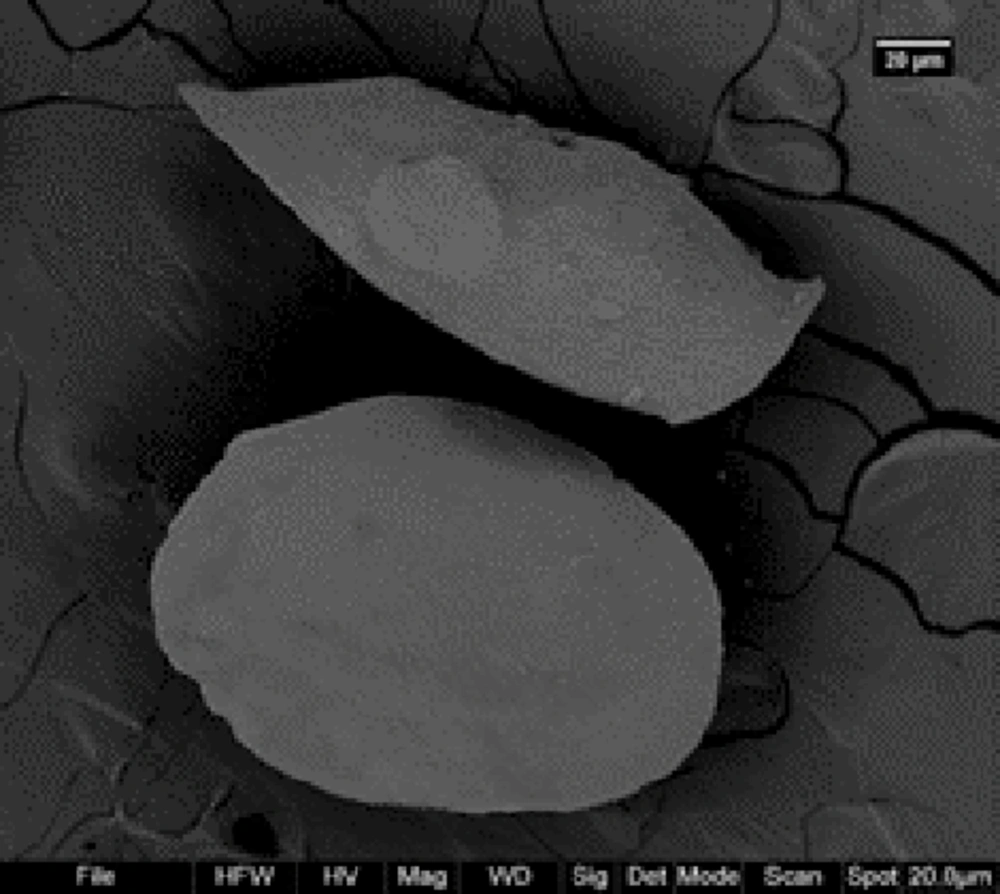

An scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to examine the shape of the beads. Calcium alginate beads were prepared at different concentrations, transferred to a liquid Mineral salt medium containing 1% oil, and incubated at 37°C and 150 rpm for 48 h. In a fume hood at room temperature, beads were dehydrated using an increasingly graded ethanol series (10, 50, 70, 90, and 100%). After this period, the shape and stability of the beads were assessed using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, MIRA 3 XM, Tescan Inc., USA). A gold sputter coating was carried out for five minutes after the samples were dried at room temperature and mounted on aluminum stubs. An acceleration voltage of 15 kV was applied to samples (14, 27, 28).

4. Results

The direct method was used for the bioencapsulation of bacteria. Calcium alginate beads were formed and encapsulated A. junii B6 as a lipopeptide biosurfactant producer. In the study of Chan and Zhang this method was used for the bioencapsulation of Lactobacillus acidophilus in alginate, and bioencapsulation protected bacteria from harsh conditions (29).

4.1. Optimization of Bioencapsulation

To determine the effects of the independent variables, the experimental design was performed according to Table 2. The concentration of calcium chloride and sodium alginate and the hardening time of beads greatly affected the production of biosurfactants by A. junii B6. The surface tension as the response was calculated using the following equation:

Surface tension = 40.64 + 1.66 (B) + 1.99 (C) - 1.31 (A × B) -1.89 (A × C) + 2.56 (B × C) + 0.59 (A ×B × C)

A, B, and C are the concentration of sodium alginate and calcium chloride and the hardening time of beads, respectively.

| Run | Value of Independent Factor | Surface Tension (mN/m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | Experimental | |

| 1 | -1 | 1 | 1 | 49.72 ± 0.04 |

| 2 | 1 | -1 | -1 | 43.11 ± 0.03 |

| 3 | -1 | -1 | -1 | 35.98 ± 0.03 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 44.08 ± 0.05 |

| 5 | -1 | -1 | 1 | 39.81 ± 0.04 |

| 6 | -1 | 1 | -1 | 38.09 ± 0.03 |

| 7 | 1 | 1 | -1 | 37.55 ± 0.06 |

| 8 | 1 | -1 | 1 | 37.07 ± 0.09 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38.09 ± 0.02 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40.08 ± 0.08 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 41.04 ± 0.08 |

The results of the measurement of surface tension in different conditions were examined by experimental design software to develop the best conditions that can describe the observed response. The validity of the proposed model was measured by the ANOVA test, the results of which are presented in Table 3.

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degree of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Value | P-Value Prob > F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 151.29 | 6 | 25.21 | 14.78 | 0.0249 |

| B | 22.11 | 1 | 22.11 | 12.96 | 0.0368 |

| C | 31.60 | 1 | 23.60 | 18.52 | 0.0231 |

| AB | 13.78 | 1 | 13.78 | 8.08 | 0.0655 |

| AC | 28.50 | 1 | 28.50 | 16.71 | 0.0265 |

| BC | 52.53 | 1 | 52.53 | 30.79 | 0.0115 |

| ABC | 2.76 | 1 | 2.76 | 1.62 | 0.2929 |

| Curvature | 2.06 | 1 | 2.06 | 1.21 | 0.3525 |

| Residual | 5.12 | 3 | 1.71 | - | - |

| Lack of fit | 0.45 | 1 | 0.45 | 0.19 | 0.7031 |

| Pure error | 4.67 | 2 | 2.33 | - | - |

A, B, and C show the main effects of the independent variables, including sodium alginate, calcium chloride concentration, and hardening time, respectively. The variables AB, AC, and BC indicate the intervening effect of sodium alginate (factor A) and calcium chloride (factor B) and hardening time (factor C).

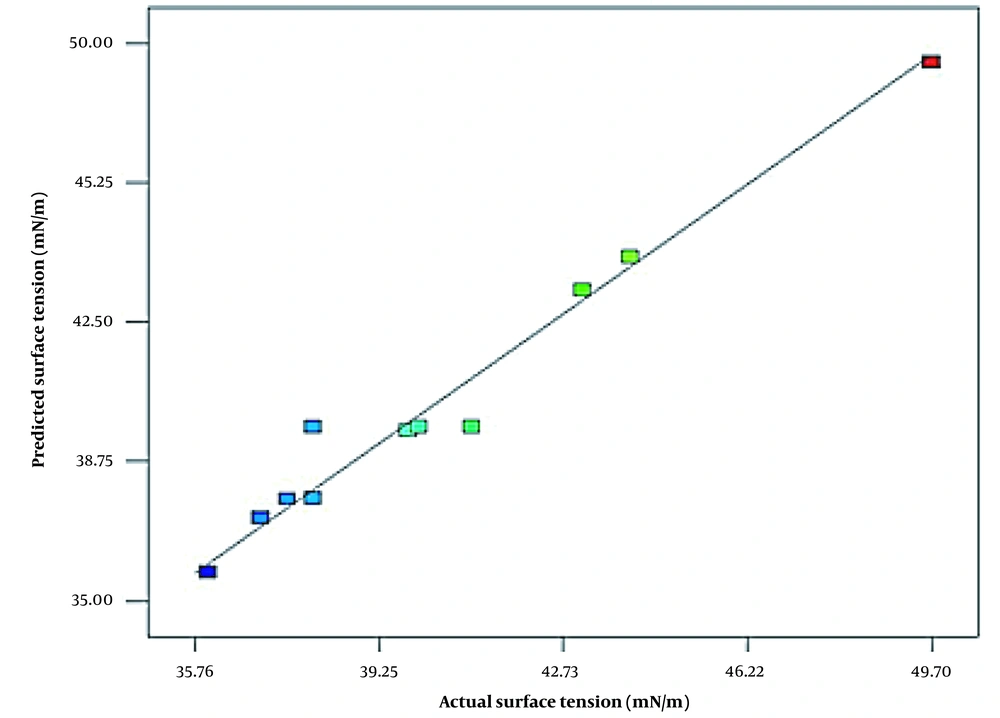

The results show that the P-value for the proposed model is less than 0.05, and therefore the proposed model was significant (P-value ≤ 0.0249). Also, the curvature (P-value ≥ 0.3525) and the lack of fit (P-value ≥ 0.7031) were non-significant. Another test used to validate the models was the linear regression test. The regression coefficients (R2 = 0.96, adjusted regression coefficient = 0.9) and predictive regression coefficient (0.75) were calculated and reported in this test. According to the results, the model has a high precision of 39.38, and the reliability of the experimental values was remarkable (coefficient of variation = 3.34%).

Calcium chloride concentration and hardening time as independent variables were significant (P-value ≤ 0.0368, P-value ≤ 0.0231, respectively). The intervening effect of sodium alginate (factor A) and calcium chloride (factor B), sodium alginate (factor A) and hardening time (factor C), and calcium chloride (factor B) and hardening time (factor C) were also significant (Table 3). Based on regression, the intervening effect of sodium alginate and hardening time (AC) has the most positive effect (coefficient = -1.89) on optimal bioencapsulation (lower surface tension). Figure 1 shows the fit of the surface tension (mN/m) values observed during the experiment (actual) and the surface tension values predicted by the software model presented.

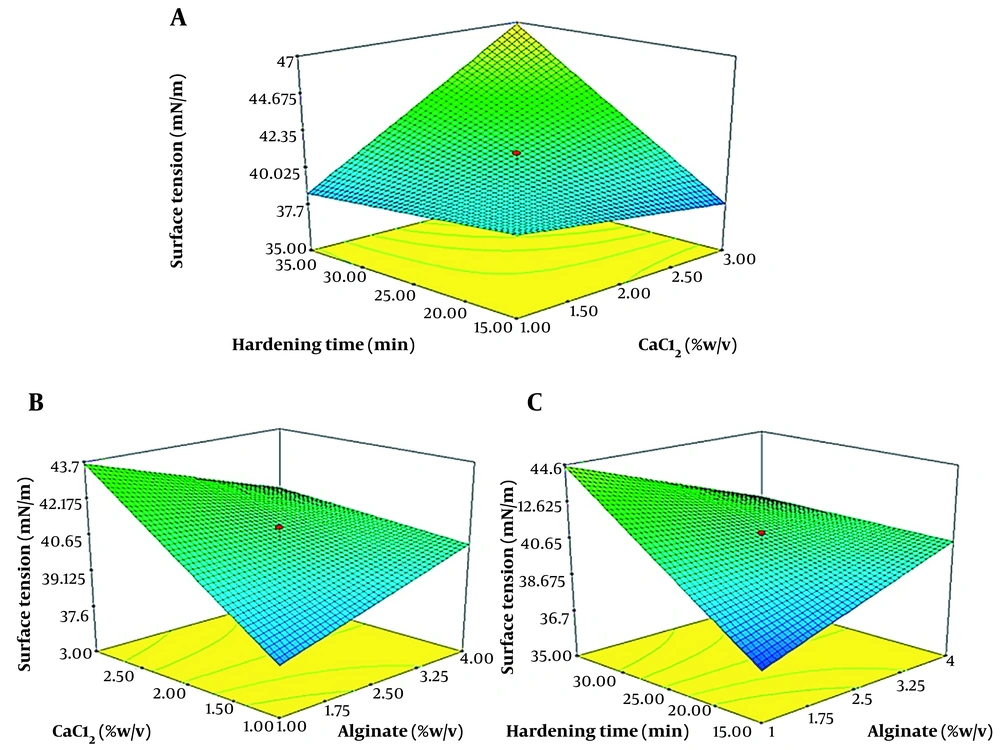

Figure 2A shows the simultaneous effect of two variables, calcium chloride and hardening time. Figure 2B shows the simultaneous effect of two variables, the concentration of calcium chloride and sodium alginate, on the production of biosurfactants and the reduction of surface tension by A. junii B6.

Figure 2C show the simultaneous effect of two variables, sodium alginate and hardening time, on the surface tension.

A, three-dimensional graph of the simultaneous effect of calcium chloride and hardening time on the surface tension; B, three-dimensional diagram of the simultaneous effect of sodium alginate and calcium chloride on the surface tension; C, three-dimensional diagram of the simultaneous effect of sodium alginate and hardening time on the surface tension

4.2. Morphology and Stability of Beads

Scanning electron microscope was used to examine the morphological characteristics of the beads, and the imaging results are shown in Figure 3. The beads were round, had a smooth surface, and had no obvious dents. The shape and stability of the beads were assessed and run 3 (lowest level of calcium chloride (1%), sodium alginate (1%), and the hardening time of 15 minutes), resulting in more stable and spherical-shaped beads.

5. Discussion

The results showed that the amount of calcium chloride and sodium alginate at the lowest level (1%) and the hardening time at its lowest level (15 minutes) had the greatest effect on the production of biosurfactants and reduced surface tension to 35.98 mN/m by A. junii B6. In the study by Wu et al. for bioencapsulation of Klebsiellaoxytoca sodium alginate and calcium chloride were optimally used and 1.5 - 2.0% and 2.0% concentrations, respectively (30). The result of this study is in contrast with our previous study that Pseudomonas aeruginosa encapsulated in alginate beads which may be because the higher concentration of sodium alginate solution became highly viscous. It isn't easy to pump, so crosslinking and bead forming are hampered and unstable (31, 32). At a high concentration of calcium chloride, bioencapsulation efficacy is decreased. This may be due to pore size reduction, resulting in diminished substrate penetration into the beads (16, 33). Also, increasing the concentration of calcium chloride, sodium alginate, and hardening time leads to harder beads, therefor decrease in the release rate of biosurfactant from inside the beads was observed. A higher coating thickness also decreased the release rate of encapsulated cells (29). Increasing the hardening time can also lead to increased cross-linking and reduced cavities, which may reduce the production of biosurfactants by reducing cell access to nutrients (34).

5.1. Conclusions

In this study, the production of a biosurfactant by alginate hydrogel encapsulated A. junii B6 was studied and optimized by experimental design. This experiment showed that a biosurfactant produced in bead formulation containing 1% solution of calcium chloride, 1% sodium alginate, and 15 minutes of hardening beads had a maximum surface tension reduction of 35.98 ± 0.03 mN/m. Finally, the practicality of this method and the possibility of creating a sequential culture system to produce biosurfactants is of great importance for potential future production and commercialization.