1. Background

Cancer is one of the main causes of death in the world. The therapeutic efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutic drugs has decreased due to their systemic side effects and multidrug resistance (MDR) (1). For this reason, the request for products containing natural ingredients or derived from natural sources has increased (2). Previous studies have reported that the regular consumption of natural products strongly reduces the risk of developing chronic diseases, including cancer (3).

Thymol (2-isopropyl-5-methylphenol), a bioactive component, is abundantly found in the oil of thyme (Thymus vulgaris) (4). It has exhibited extensive biological actions, including anti-microbial (5), anti-fungal (6), anti-oxidant (7), anti-inflammatory (8), anti-parasitic (9), and anti-cancer (10) activity and wound healing properties (8). It is also considered an interesting ingredient in the food industry due to its generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status (4). Thymol has shown protective effects against cancer cells and can be considered a new approach for cancer treatment in clinical practices (1). However, despite its potential, employing thymol in the food industry and medicinal applications is limited owing to poor water solubility (4), high volatility, low bioavailability, and susceptibility to oxidation, heat, and light (7, 8).

In this context, nanotechnology can be a promising approach to improve natural compounds' physicochemical properties and efficacy. Various nanocarriers are considered drug delivery systems to improve cancer therapy, including micelles, polymeric nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, liposomes, dendrimers, nanostructured lipid carriers (NLC), and solid lipid nanoparticles. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) are nanocarriers that contain biocompatible and physiologically active lipids. They are widely considered drug delivery systems due to their capability to encapsulate both lipophilic and hydrophilic drugs (11, 12), biodegradability, bioavailability, stability (4), sustained release of drugs, non-toxicity (11), flexible surface functionality (13), prolonged circulation in the body (14), and suitability for large-scale production (15).

According to the previous reports, SLNs do not display the restrictions associated with polymeric nanoparticles and liposomes, including sterilization, toxicity, and long-term stability. Moreover, these carriers show advantages over other drug delivery systems, such as high encapsulation efficiency, improved physical stability, sustained drug release, easy large-scale production, and increased bioavailability (16-18). It was established that the docetaxel-loaded SLNs showed lower IC50 and higher effectiveness than free docetaxel. Moreover, docetaxel-loaded SLNs induced more apoptosis pathways than free docetaxel in cancer cells (19). In vitro cytotoxicity and in vivo antitumor studies indicated that SLNs could be a promising principle for doxorubicin delivery and provide a new perspective for breast cancer treatment (20). It has been reported that 1,3-diacylglycerol (DAG) SLNs can be used as a promising nanocarrier for loading thymol with high encapsulation and stability (4).

2. Objectives

Encapsulation of thymol in SLNs may decrease its limitations and improve its efficacy. Therefore, the current study aimed to prepare and characterize thymol-loaded SLNs (T-SLNs) and evaluate the cytotoxic activity against cancer cells.

3. Methods

Stearic acid, thymol, glyceryl monostearate (GMS), and Tween 80 were obtained from Merck, Germany. Also, 5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Germany. We obtained HT-29 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma) cell lines from the Iranian Biological Resource Center (IBRC) of Iran. Other chemicals and solvents were of analytical grade and purchased from Merck, Germany.

3.1. Preparation of Solid Lipid Nanoparticles

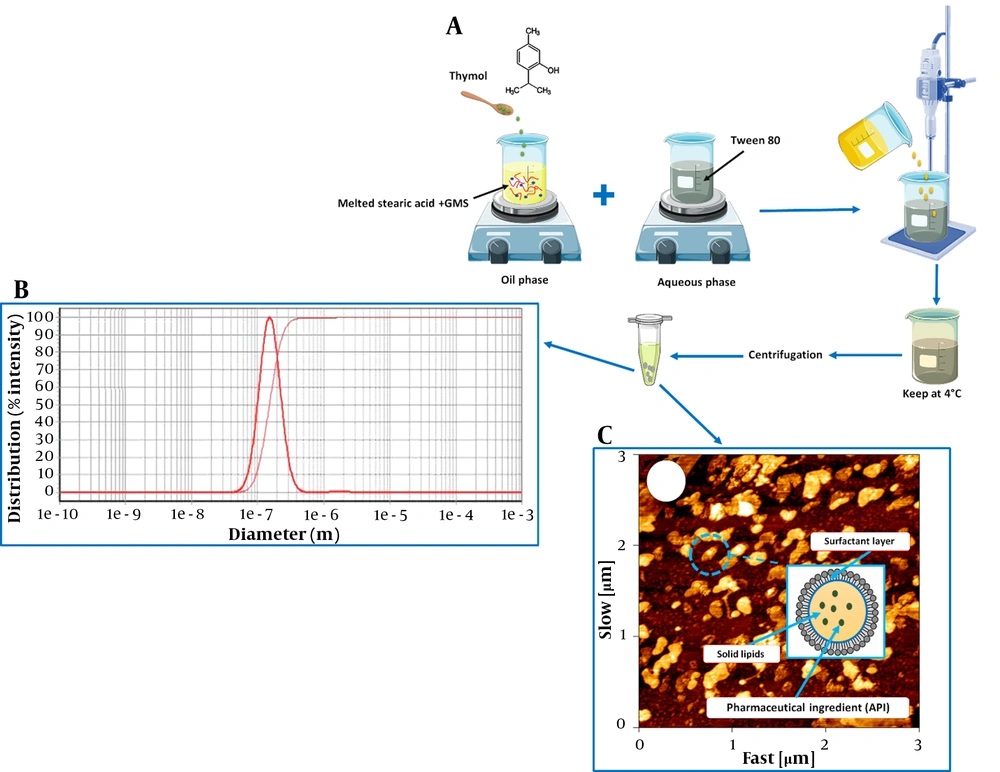

Solid lipid nanoparticles were prepared using a microemulsion method. Briefly, stearic acid (300 mg) and GMS (100 mg) were heated at 70°C. Then, thymol (10 mg) was incorporated into the molten lipid. To prepare the aqueous phase, Tween 80 (300 mg/10 mL) was heated at 70°C. Then, the lipid phase was added dropwise into the aqueous phase under a homogenizer (Heidolph, Germany) at 24,000 rpm for 10 min. After homogenization, the obtained suspension was cooled at 4°C for 1 h. After centrifugation of the suspension at 20,000 rpm for 30 min (MPW-350R, Poland), the pellets were washed three times using distilled water and then freeze-dried at -50°C (2 Pa) for 24 h (Operon, Korea). The steps of SLNs preparation are shown schematically in Figure 1A.

3.2. Determination of Encapsulation Efficacy

An indirect method was utilized to calculate encapsulation efficiency. The concentration of free thymol in the supernatant was measured using a UV spectrophotometer (Biochrom WPA Biowave II, England) at 297 nm after centrifugation. Encapsulation efficacy (EE%) was calculated using Equation 1:

Where Wa is the initial amount of thymol added, and Ws is the amount of remaining free thymol in the supernatant of centrifuged samples and determined by a UV spectrophotometer.

3.3. Particle Size and Morphology Study

The particle size of the sample preparations was analyzed using a particle sizer (Qudix, ScatterOScope I, Korea) at 25°C. The surface morphology of SLNs was also determined by atomic force microscopy (AFM) (Nano Wizard II, JPK, Germany). Also, SLN samples were diluted with double distilled water to a 1:100 ratio before each measurement.

3.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Analyses

Fourier transformed infrared (FT-IR) spectra of free thymol and thymol-loaded SLNs were performed by an FT-IR spectrometer (Vertey 70, Bruker, Germany). Pellets were prepared by mixing the samples with KBr and scanned from 500 to 4000 cm-1 at 25°C.

3.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed to investigate the interaction between nanocarriers and molecules of the drug. Thermal analysis of thymol and thymol-loaded SLNs was performed using a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC-1 Mettler Toledo, Switzerland). The samples (5 mg) were sealed in aluminum pans and analyzed at a heating rate of 10°C min-1 from 0°C to 250°C for 30 min.

3.6. In vitro Drug Release

The in vitro release study is a critical test to assess the drug release rate at different times. For this purpose, 2 mg/mL of thymol-loaded SLNs was taken in a dialysis bag (MW cutoff of 12 kDa), placed in a beaker containing 10 mL of ethanol 10% (v/v) at 37°C, and stirred at 100 rpm. At different time intervals, 1 mL of the medium was discharged for analysis and replaced with an equal volume of fresh medium. The released amount of thymol was determined using a UV spectrophotometer. The mechanism of thymol release from SLNs was also determined according to different mathematical models, including zero-order, first-order, Weibull, linear Wagner, logarithmic Wagner, Hixcon, Higuchi, and Korsmeyer-Peppas models.

3.7. In-vitro Cytotoxicity Assays

The MTT assay was used to determine the cytotoxicity of formulations. Cytotoxicity assays measure the ability of cytotoxic compounds to cause cell damage or cell death. Briefly, HT-29 cells were seeded at a cell density of 5 × 103 cells/well in 96-well tissue culture plates and incubated overnight. After 24 h, the medium was removed, and the cells were treated with different concentrations of free thymol, SLN, and T-SLN at concentrations of 5, 25, 50, 75, and 100 µM for 24 h. Next, 20 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added into each well and incubated further for 4 h. Then, formazan crystals were dissolved by adding 100 µL of DMSO and shaken for 20 min. Cellular viability was determined using an ELISA plate reader (BioRad, USA) at 570 nm according to Equation 2:

Where Abssample and Abscontrol are the absorbance of the sample and positive control, respectively. According to the cell viability values, IC50 (inhibitory concentration to produce 50% cell death) was also determined.

3.8. Hemolysis Assay

The hemolysis test is used to study the degree of RBCs destruction induced by the nanocarriers. The rat blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 5 min and washed thrice with PBS. Then, 100 µL of the erythrocyte suspension was added to 900 µL of SLNs at different concentrations (0.1, 0.5, and 1 mg/mL) and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. After incubation, samples were centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 10 min. Then, the hemoglobin release rate in the supernatant was determined using UV spectrometry at 540 nm. Also, PBS and distilled water were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. Finally, Equation 3 was used to calculate the hemolysis percentage.

Where As, Anc, and Apc are the absorbance of the sample, negative control, and positive control, respectively.

3.9. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and all data were presented as mean ± SD. For comparative purposes, one-way ANOVA was employed, and P < 0.05 was assumed statistically significant.

4. Results and Discussion

Essential oil components have several applications in various fields, from the pharmaceutical to food industries (21). Thymol has potential applications, including anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and anti-cancer activity (1, 22-24). However, its practical applications are restricted due to low stability, high volatility, and low bioavailability (25). Entrapment of thymol into SLNs can improve its chemical stability and solubility. According to the results, EE% of thymol in SLNs was 63%, and the average size of SLNs was 145 nm (Table 1). According to the previous study, stearic acid is used to prepare SLNs, as it increases the highest entrapment efficiency in nanocarriers. Therefore, in this study, it was chosen as a lipid core for SLNs preparation (26). The size distribution of SLNs is shown in Figure 1B. The intracellular uptake of nanoparticles depends on their size and shape. Nanoparticles with a 120 - 150 nm size are mostly internalized through caveolin or clathrin-mediated endocytosis (27). Encapsulation of drugs in 100 - 150 nm nanoparticles may improve drug penetration to tumor tissue due to enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect (28). In the current study, the average size of particles was about 145 nm, allowing particles to place inside tumor cells. As shown in Figure 1C, AFM images confirm the spherical shape of SLNs. It has been reported that the therapeutic efficiency of spherical nanocarriers is much higher due to their ability to encounter minimum membrane bending energy during endocytosis (29).

| Formulation | EE% | Particle Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Th-loaded SLNs | 63 | 145 |

Characteristics of Thymol-loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles

4.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Analyses

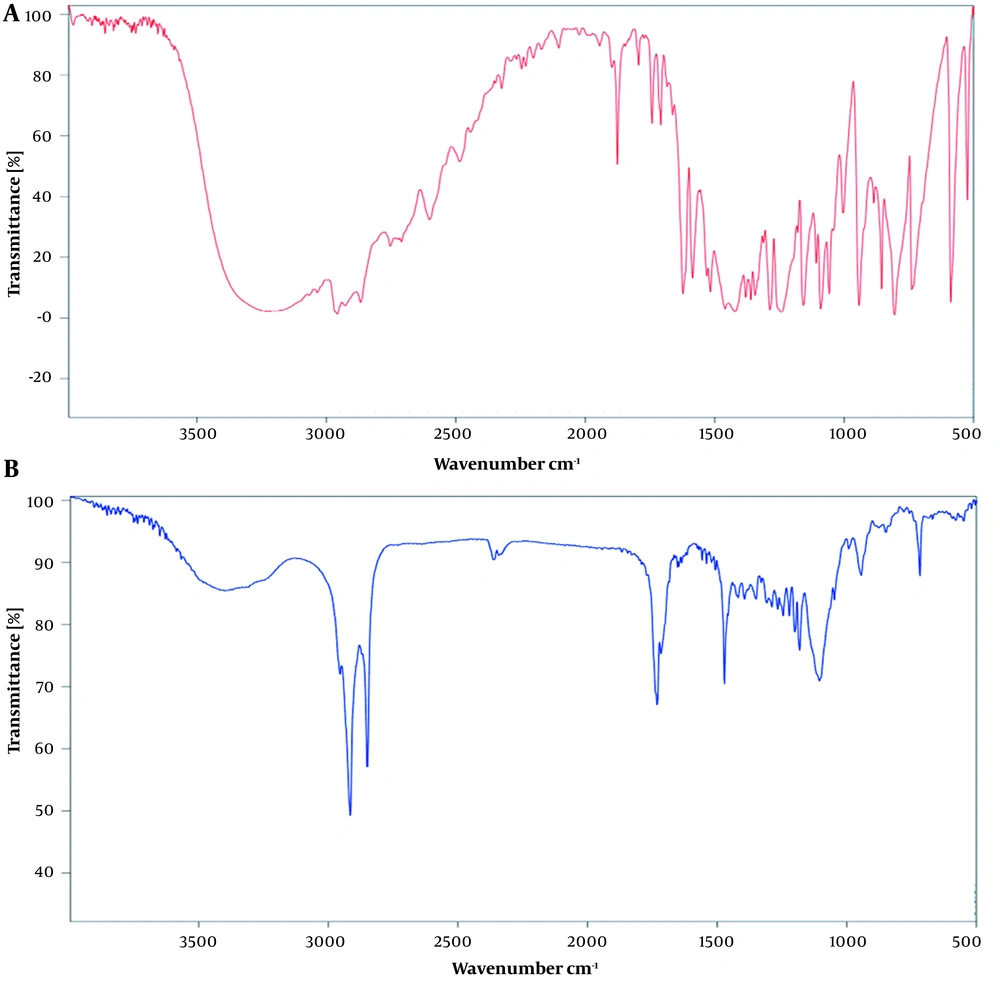

The FTIR spectra of thymol and thymol-loaded SLNs are shown in Figure 2. A broad band in the range of 3000 - 3500 cm-1 was shown in the thymol spectrum due to -OH group (Figure 2A). This peak in thymol-loaded SLNs confirms the loading of thymol in SLNs (Figure 2B). Similar findings reported by Zamani et al. showed that hydrogen bonding induced phenolic hydroxyl stretching, which, in turn, led to the formation of a bond in the 3229 cm-1 region of the thymol spectrum (30).

4.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry Analysis

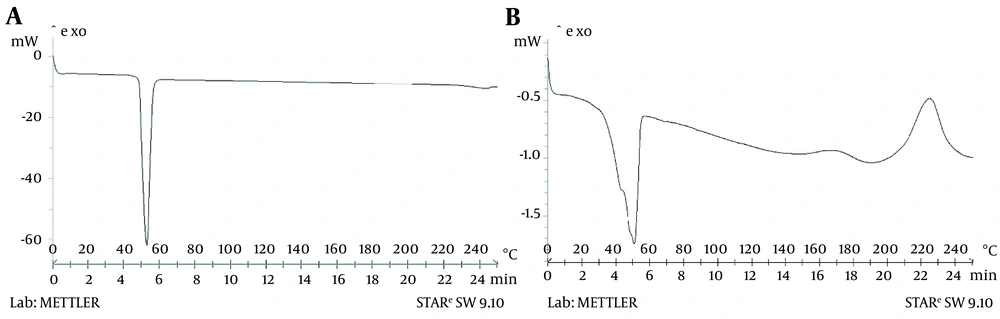

Differential scanning calorimetry investigated the thermal behavior of thymol and thymol-incorporated SLNs. The DSC thermograph of thymol displayed an endothermic peak at 52°C that corresponds with the thymol endotherm reported in the literature (Figure 3A) (31). As shown in Figure 3B, the thymol peak in SLNs indicates the physical encapsulation of thymol in nanoparticles. Similar results were reported by Zamani et al. for DSC analysis of thymol loaded within microparticles (30).

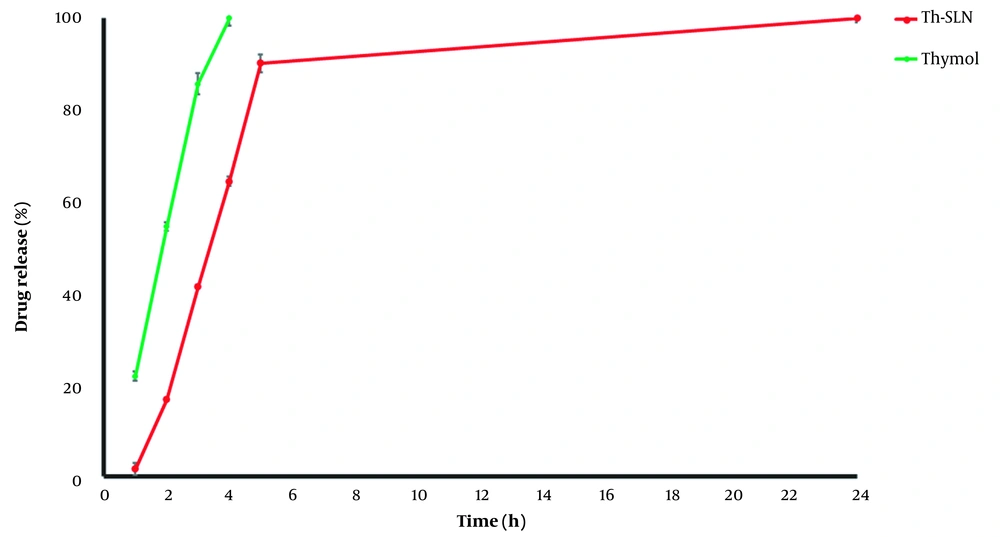

4.3. In vitro Release Study

According to the findings, free thymol was rapidly released within four hours. As shown in Figure 4, a primary rapid release of thymol from SLNs occurred due to the drug adsorption on SLNs surfaces. Then, a sustained release behavior was observed because of the gradual release of thymol from particles into the diffusion medium. In addition, the in vitro release profile of thymol from SLNs was fitted to zero-order, first-order, Hixson, Korsmeyer-Peppas, Higuchi, linear Wagner, logarithmic Wagner, and Weibull models (Table 2). As shown in Table 1, the Weibull model was found to be the best-described thymol release pattern from SLNs at the first five hours due to the highest R-square value and least mean percentage error (MPE%). The Weibull model describes a release mechanism by which the drug release rate is affected by diffusion, dissolution, and mixed dissolution-diffusion processes (32). The current results align with Chokshi et al., who reported that the release profile for Rifampicin-loaded SLNs followed the Weibull model (33). Li et al. reported that the Weibull model was the best-fitting model to describe the Tetrandrine release pattern from SLNs (32). Khames et al. indicated that the release of natamycin from SLNs followed the Weibull model (34). In addition, our results are consistent with Andrade et al. findings which reported that the release of praziquantel from SLNs was fitted to the Weibull model (35). However, our findings are contrary to the results of Chantaburanan et al., which showed the release of ibuprofen was fitted to Higuchi's kinetics (36). Furthermore, Kushwaha et al. revealed that the release of raloxifene hydrochloride from SLNs had higher linearity with the Higuchi model (37). According to these results, it can be concluded that SLNs can be appropriate nanocarriers for the sustained release of thymol.

| Parameters | Models | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero-order | First Order | Higuchi | Korsmeyer–Peppas | Hixcon | Weibull | Linear Wagner | Logarithmic Wagner | |

| R2 | 0.9930 | 0.8682 | 0.9625 | 0.9716 | 0.9293 | 0.9948 | 0.9874 | 0.9729 |

| MPE% | 48.82 | 405.29 | 99.12 | 25.42 | 209.69 | 7.99 | 17.74 | 15.67 |

Regression Coefficient and Mean Percentage Error Obtained After Fitting the Data of Thymol Release from Solid Lipid Nanoparticles to Mathematical Models

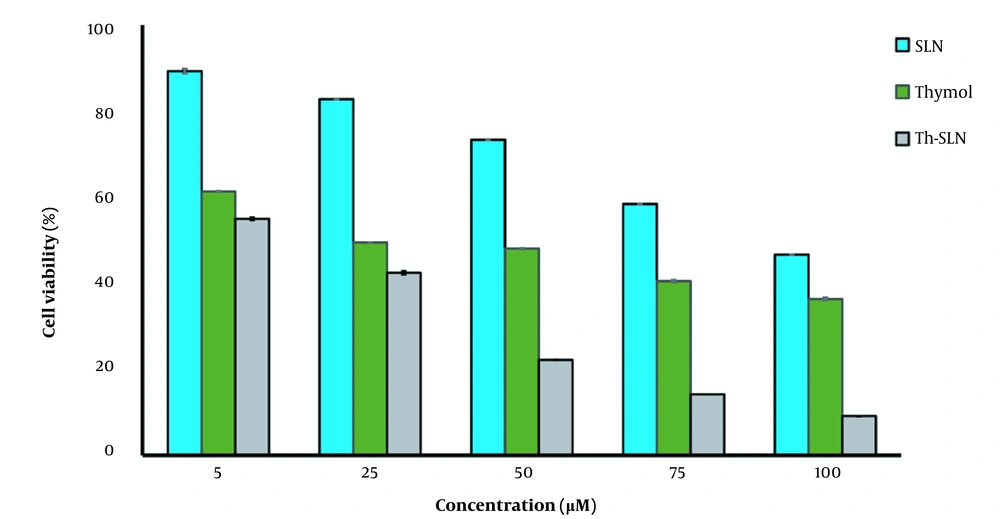

4.4. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

As presented in Figure 5, thymol-loaded SLNs (Th-SLNs) were more cytotoxic than free thymol and blank SLNs (P < 0.05). The IC50 values for thymol, SLNs, and Th-SLNs were 39.22 ± 0.9, 94.87 ± 1.1, and 7.88 ± 0.7 μM, respectively (Table 3). Blank-SLN had a negligible effect on cell viability, indicating that SLN compositions are biocompatible and appropriate for drug delivery. As expected, the viability of cells reduced with increasing the concentration of thymol. According to the results, Th-SLNs are more efficiently taken up by cancer cells than free thymol. These findings could be related to the different cell uptake pathways between thymol-loaded SLNs and free thymol. According to previous studies, endocytosis is the main cellular uptake pathway for nanoparticles in cancer cells (27). Consequently, the higher efficiency of thymol-loaded SLNs may be associated with effective endocytosis of SLNs in cells, resulting in more internalization of thymol in cancerous cells. On the other hand, it has been reported that thymol triggered apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway in the bladder (38) and breast cancer cells (23). Also, it has been reported that thymol exhibits anti-cancer activity by activating the Bcl-2/Bax protein, an apoptosis regulator (23).

| Formulation | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|

| Thymol | 39.22 ± 0.9 |

| SLNs | 94.87 ± 1.1 |

| Th-SLNs | 7.88 ± 0.7 |

The IC50 Values for Thymol, Solid Lipid Nanoparticles, and Thymol-loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles

Additionally, several studies reported that encapsulating essential oil in SLNs increases anti-cancer activity. Valizadeh et al. prepared SLNs containing Zataria multiflora essential oil to improve anti-cancer activity against breast and skin cancer. They found that essential oil loaded in SLNs had a more remarkable anti-cancer effect than free essential oil on cancer cells (17). Dousti et al. evaluated the anti-cancer activity of Pistacia atlantica essential oil loaded in SLNs against breast cancer. It was observed that essential oil loaded in nanocarriers could trigger more apoptosis in breast cancer cells than free essential oil (39).

According to previous studies and our results, the effective cytotoxic activity of thymol-loaded SLNs may be because it promotes apoptosis in cancer cells more than free thymol. However, further studies are required to confirm these results.

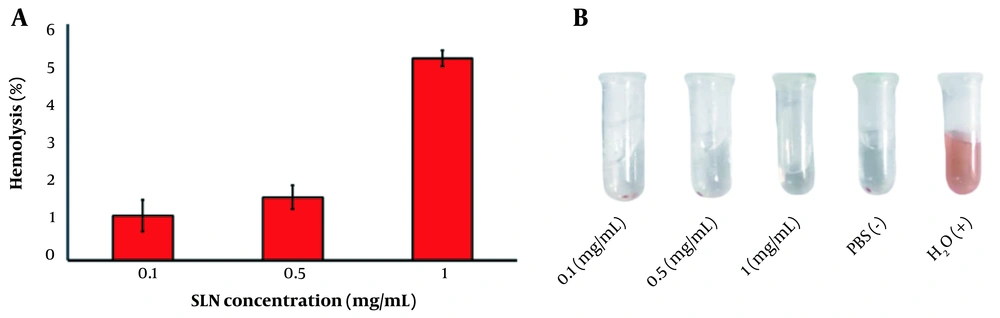

4.5. Hemolysis Assay

A hemolysis study was performed to evaluate the intravenous safety of SLNs. As presented in Figure 6A, the hemolysis percentage of SLNs at different concentrations was less than 5%. A hemolysis rate of less than 5% is considered safe (40). Moreover, the RBCs treated with H2O (as positive control) and PBS (as negative control) displayed significant and non-significant hemolysis, respectively (Figure 6B). These results indicated the biocompatibility of SLN compositions, in line with previous studies reporting that SLNs are hemocompatible (41, 42). For example, Sahib et al. and Veider et al. reported insignificant hemolysis caused by SLNs (43, 44).

4.6. Conclusions

According to the obtained results, thymol was successfully encapsulated into SLNs. The 145 nm SLNs with a narrow size distribution and EE% of 63% were obtained. The in vitro release study showed the sustained release of thymol from SLNs. The anti-cancer activity of thymol-loaded SLNs was more effective than that of free thymol. Moreover, the hemolysis assay indicated that SLNs were hemocompatible, supporting their intravenous injection safety. Based on these findings, SLNs can provide a platform to improve the efficiency of thymol and other essential oil components for future cancer treatment. However, comprehensive in vivo studies are needed to evaluate the detailed effects and side effects of SLNs as nanocarriers.