1. Background

Need assessment is a tool for planners to help them decide on various aspects of a program, including the necessity of designing and implementing a training course, improving the presentation and transfer of concepts, and even the topics of a course (1). In this regard, it is possible to provide a background for better, more desirable, and efficient future courses by referring to the comments and requests of the participants (2).

Medical science is enormously progressive. According to some reports, every 5 - 4 years, the volume of information in this area is doubled, while many scholars believe that medical findings in the last 7 - 10 years are 75% - 70% old (3, 4). It is significant to acquire the participants’ viewpoints of continuing medical education (CME) about various aspects of these programs (5, 6).

It has been shown that participants in CME programs are most motivated to increase knowledge and improve patient care (7). Also, their evaluation of CME programs adapting to scientific innovations and appropriate contribution to their job requirements has motivated them to update the previous information (8).

The medical community always needs to be informed about the latest scientific findings and the country’s health policies and reinforce and update the previous knowledge (9). Unfortunately, some participants in CME programs stated that their educational needs were not evaluated before implementation (10).

Since the beginning of this profession, the importance of CME programs for pharmacists has always been emphasized (11). Continuing professional education enables pharmacists to become aware of new topics in pharmaceutical care and perform better in national health services (6).

2. Objectives

The current study is about the needs assessment of education in CME programs by assessing the pharmacists’ points of view and motivation for more active participation in these programs.

3. Methods

Data were obtained from a descriptive cross-sectional study in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IUMS), (2013 to 2018), and 145 Pharmacists were randomly assigned among participants According to this equation, we needed at least 120 participants. If we lost 20% of the participants during the study, with 145 people entered, there would still be 120 participants left. For this reason, the study began with 145 people.

n, The total number of participants in CME courses in Isfahan province, which is 450 people.

z, Confidence coefficient 0.95 percent, which becomes 1.96.

s, Estimation of the standard deviation of the need score from the participants’ point of view, which is a maximum of 16.7% (1/6 of 100 and considering that the minimum need score is zero and the maximum is one hundred).

d, the accuracy rate that is considered 2.5 percent.

Self-administered questionnaires were used, and their face and content validity and reliability were evaluated by CME experts and Cronbach’s alpha measurement, respectively (alpha = 0.8) (12, 13).

The statistical population consisted of all graduates in pharmacy (Pharm.D.) in Isfahan Province, Iran. To this end, 150 participants in the CME course have entered the study, which was entirely selective and with full consent from the volunteers. The initial questionnaire was originally examined by the executives and a group of experts on the issues of CME in the university and after the necessary amendments. In cases where more than one option is selected, it is considered as missing.

The questionnaires were distributed manually at regular sessions of CME; the volunteers were asked to answer freely and carefully.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

The obtained data were expressed separately; descriptive statistics were presented in figures and tables and analyzed with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s to indicate the statistical difference. Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 20.0), and the figures were drawn using Microsoft Office software (version 2010).

4. Results

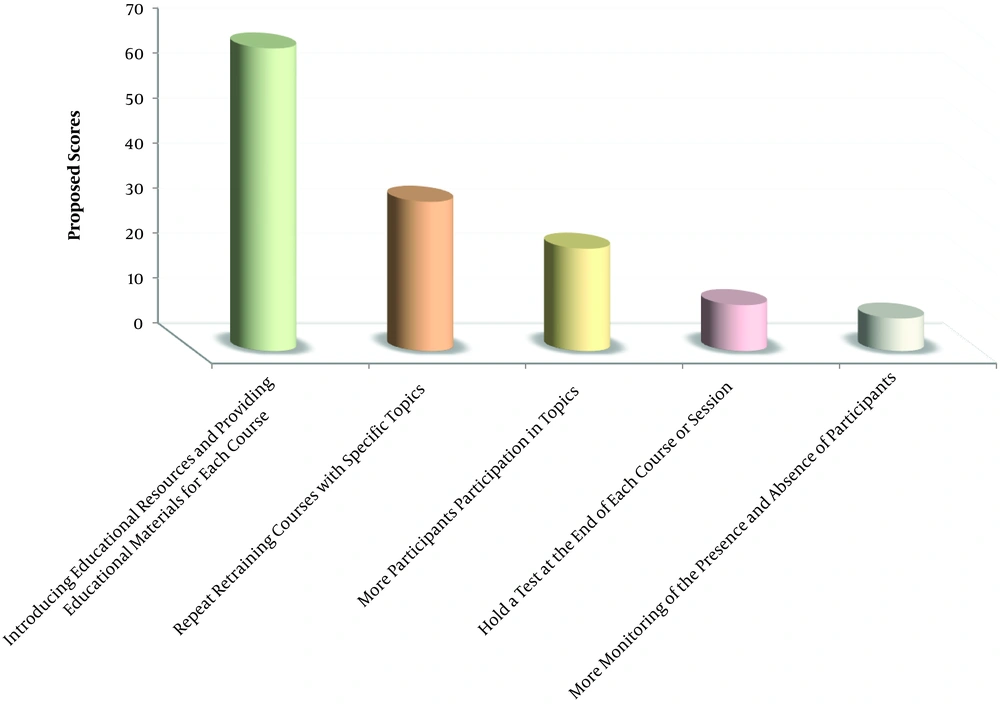

Figure 1 demonstrates the main strategies for providing suitable CME from the pharmacist participants’ point of view. The main proposed plans for providing a useful CME were introducing educational resources, providing learning materials, and repeat retraining courses with specific topics.

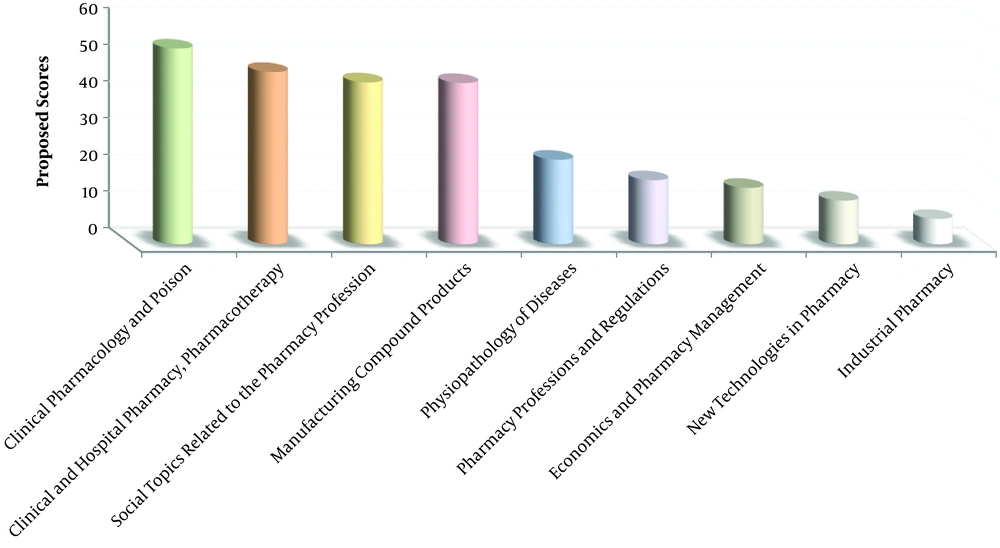

Figure 2 shows the priority of main topics to be offered in CME from the perspective of pharmacists. Most pharmacists insisted on the applied aspects of CME programs and clinical pharmacology. Hospital pharmacy and pharmacotherapy were the main topics offered in CME from the perspective of all pharmacists. Experienced pharmacists agreed more in this regard (Table 1).

| Priority (1 to 9) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Work Experience, y | ||||||||

| Topics | Male | Female | P Value | 1 - 5 | 6 - 10 | 11 - 15 | 16 - 20 | 20 < | P Value |

| Clinical pharmacology and poison | 3 | 2 | N | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | N |

| Clinical and hospital pharmacy, pharmacotherapy | 4 | 1 | < 0.01 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 8 | < 0.001 |

| Social topics related to the pharmacy profession | 1 | 5 | N | 5 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | N |

| Manufacturing compound products | 2 | 3 | N | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | N |

| Physiopathology of diseases | 7 | 4 | < 0.05 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 7 | < 0.001 |

| Pharmacy professions and regulations | 6 | 6 | N | 6 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 4 | N |

| Economics and pharmacy management | 5 | 8 | < 0.05 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 5 | N |

| New technologies in pharmacy | 8 | 7 | N | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 6 | N |

| Industrial pharmacy | 9 | 9 | N | 7 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | N |

Abbreviation: N, non-significant difference.

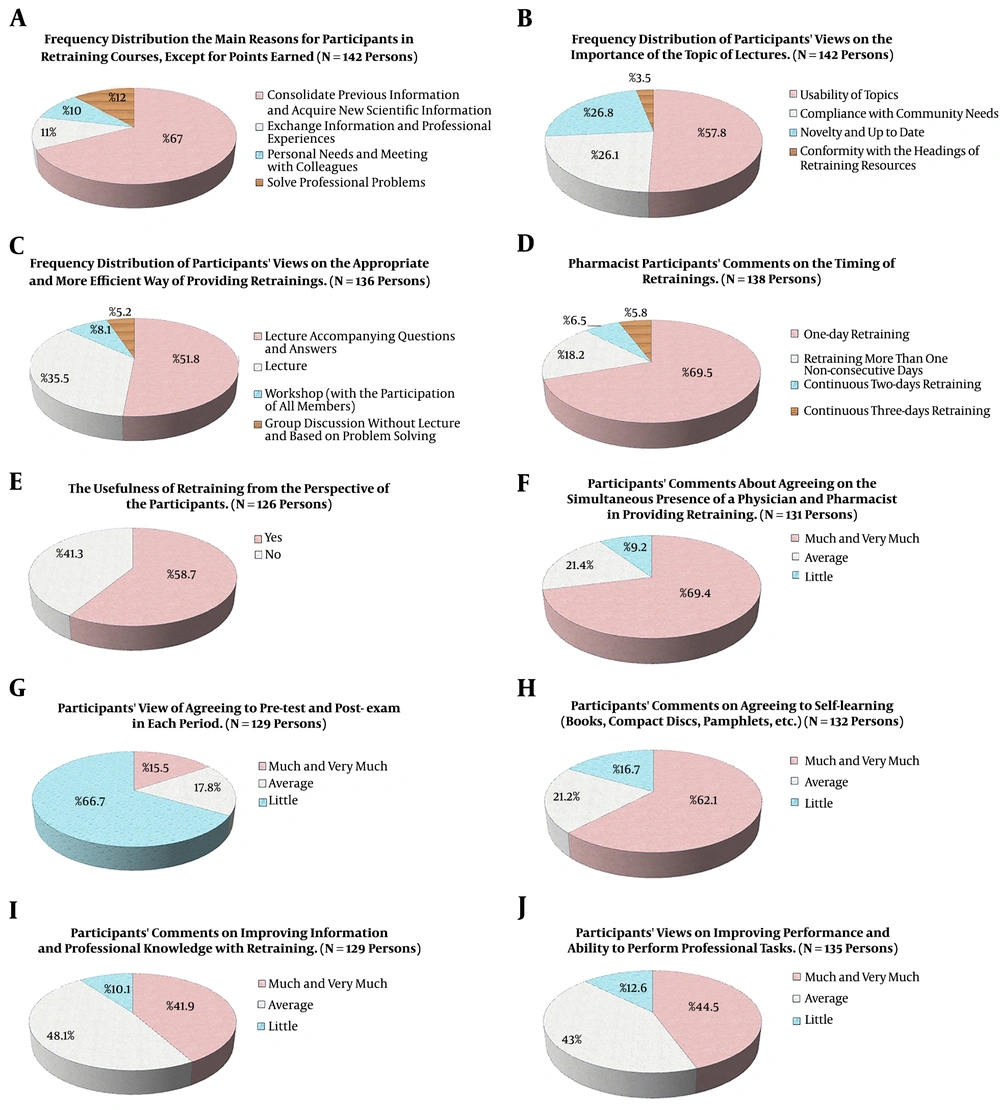

Figure 3 illustrates the pharmacist’s comments and perspective about a perfect CME program. According to the participants, the main reasons for participating in CME programs were the consolidation of their previous learning and acquiring new knowledge (84.5%), and they agreed with problem-based and self-learning. The simultaneous presence of pharmacists and physicians was preferred, and the usefulness of retraining was emphasized. Fifty-two percent of contributors selected a combination of lecture and panel discussion as a suitable method for CME presentation. The programs’ levels in science, experience, and skills or attitude promotion were evaluated high and very high by 41.9 and 44.5% of pharmacists, respectively. However, participants often disagreed with the pre-test as well as long-term and multi-day programs.

More than half of the participants stated that their professional knowledge and skills increased significantly with CME programs, which helped increase their ability to perform professional tasks. The necessity and usefulness of CME were confirmed from the perspective of the participant.

5. Discussion

Our data represent the educational needs assessment in CME programs by assessing the pharmacists’ points of view and motivation for more active participation in these programs. The present study revealed that most community pharmacists in CME programs of IUMS had desirable attendance and cooperation with this investigation. It seems that CME programs were reasonably in accordance with their anticipations and expectations. Data in pharmacists’ viewpoints and similar studies on other medical team members about CME programs shows that their most important motivation for participating was to increase knowledge and awareness about new scientific achievements (7, 8).

In accordance with our findings, almost the majority of participants stated that their educational needs were related to the topic of the CME (14, 15). However, in some other studies, participants learn some information that is not appropriate for their professional responsibility (16).

Data showed that clinical pharmacology, hospital pharmacy, and pharmacotherapy have been the most popular topics in CME programs. In recent years, the role of pharmacists in the therapeutic team and especially clinical pharmacists in the prescribing and rational use of medications have received much attention; therefore, the programs with these topics should be a priority (17). These training programs can help them identify adverse drug reactions earlier than physicians, thereby reducing high healthcare costs (18).

In this study, self-learning was the focus of the participants. Participants also noted that lecture accompanying questions and answers is a better approach in CME, but a pre-test (pre-test (preliminary exam before the lecture)) is not necessary. Previous studies have confirmed that collaborative, cooperative, and problem‐based teaching methods are more effective in enhancing lifelong learning; it is also considerably better to replace traditional methods in continuing education programs (19-21).

Updating information in CME was another interesting topic reported strongly in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics (22). Up-to-date information on CME is an important issue in education. It may be argued that the most important reason for holding CME programs is the obsolescence of information in medical sciences and pharmaceutical care (23, 24).

A combination of online and face-to-face CME programs can increase the ease of access and the right choice of the desired program (25). Also, a model based on blended learning (a combination of online and face-to-face methods) will have better performance (26).

In order to reconcile pharmacists’ educational needs with CME programs and prevent the waste of time, planners obligate to do more accurate needs assessments reasonably. All programs should be tailored to the needs and proficiency of the audience, and before implementation, information levels of participants should be measured to achieve better results. Training programs can improve the quality of function and satisfaction of human resources if they are correct, principled, and based on needs.