1. Background

In the current digital era, creativity is of crucial importance for both individuals and societies. Creativity and productivity have remarkable individual, group, organizational, and social advantages that should not be considered in silo (1).

Tiwari, in the Encyclopedia of Education, defined creativity as a mental or artistic initiative (2). Savile has defined creativity as a state of mind in which multiple intelligences function in integrity. Creativity empowers individuals and helps them achieve significant innovations. Therefore, it can be argued that creativity is the means to achieve a goal, not the goal itself (3).

Torrance defined four factors for creativity: 1- fluency: the talent to propose several ideas, 2- Originality: capturing the novelty of ideas, 3- Flexibility: the talent to produce many different ideas and methods, and 4- Elaboration: talent to pay attention to details (4).

During the past decades, there have been several studies on creativity, which investigated both the characteristics of creative people, the answer to these two following questions (5):

1. Can creativity be taught? If yes, how?

2. Can we measure creativity? If yes, how?

Creativity has recently been discussed in schools and universities. It is clear that education should be a dynamic process, and students should actively participate in the learning process and create new ideas via creative thinking, which helps them find different solutions in terms of the situation and context. This goal is not achievable unless it is taught in educational environments such as universities. Therefore, university professors ought to use creative teaching methods to lay the groundwork for students to develop creativity, which in turn is useful for solving future problems (6). In today’s world, students should be equipped with critical and creative thinking skills to make appropriate decisions and solve complex problems in society (7).

2. Objectives

Since the most significant indicator to assess the quality of higher education is creativity, measuring the creativity of medical students would provide useful information for university authorities. Hence, the current study aimed to investigate the creativity of postgraduate students of the Medical School of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences to provide necessary information for making decisions.

3. Methods

The current study is a descriptive-survey in which all ethical considerations were observed. Participants were ensured about the confidentiality of the information and were informed that the participation is voluntary and harmless. The study population was all graduate students of the Medical School of Shahid Beheshti. They were selected using a two-stage cluster sampling technique. Thus, we prepared a list of departments with postgraduate students. Then, we selected the majors randomly (anatomy, pharmacology, physiology, parasitology, biochemistry, microbiology, genetics, immunology, medical physics, and biomedical engineering). Afterward, we selected several students from each selected cluster. The sample size of 265 subjects was calculated using the Cochrane formula. 17 subjects were excluded due to the incompleteness of questionnaires, and 11 were excluded due to missing data. Therefore, in total, data of 237 subjects were analyzed.

Abedi's creativity test (ACT) was used to collect data based on the theory of Torrance (5). The ACT comprises 60 items categorized in four sub-scales, scoring on a three-point Likert scale ranging from zero ("low creativity") to three ("high creativity"). The total score is the sum of each sub-scale, which indicates the overall creativity. For each subscale, the total score ranges from 60 to 180. A score of less than 100 indicates "low creativity", between 100 and 150 "moderate creativity", and more than 150 "high creativity".

We evaluated the face validity and content validity of the ACT. Face validity was assessed in two parts. In the first part, the questionnaire was given to ten medical students, and in the second part, the questionnaire was given to ten experts. They were asked to provide their opinions. We used the Lawshe method to assess the content validity of the ACT (8) based on three-points of "very relevant ", "item needs some revision" and "not relevant". Ten experts offered their opinions, based on which the minimum acceptable validity coefficient was 0.62. The CVR of the ACT was 0.80, which was acceptable. The test-retest method was used to evaluate the reliability of the questionnaire. Therefore, 30 subjects were randomly selected from the study population so they could complete the questionnaire in two periods of time with a one-week interval. Then, the correlation coefficient between the scores was obtained, and the test-retest test for the questionnaire and its dimensions were calculated (Table 1). The significance level of the questionnaire and its subscales was less than 0.01.

| Domain | Number of Items in Each of Scale | Cronbach Alpha Coefficient | ICC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluency | 22 | 0.80 | 0.76 |

| Flexibility | 11 | 0.89 | 0.88 |

| Originality | 16 | 0.88 | 0.85 |

| Elaboration | 11 | 0.75 | 0.81 |

| Overall | 60 | 0.83 | 0.82 |

Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated for all subscales of the questionnaire to measure the internal consistency of the scales (Table 1), which was higher than 0.7 for all sub-scales.

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 18 and Excel via descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation, etc.). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to test for a normal distribution. The association between students' creativity and demographic variables was assessed using t-test, Mann-Whitney, and Kruskal–Wallis.

4. Results

Table 2 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. Most of the participants (62.4%) were in the age group of 25 to 30 years and were educated up to M.Sc. Based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, dimensions of fluency (P-value = 0.074) and creativity (P-value = 0.17) were distributed normally. While flexibility and elaboration were normally distributed.

| Variables | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 128 | 54 |

| Male | 109 | 46 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 189 | 79.7 |

| Married | 48 | 20.3 |

| Age | ||

| < 25 | 62 | 26.2 |

| 25 - 30 | 148 | 62.4 |

| 30 - 35 | 18 | 7.6 |

| > 35 | 9 | 3.8 |

| Education | ||

| Master | 202 | 85.2 |

| PHD | 35 | 14.8 |

| Departments | ||

| Anatomy | 26 | 11 |

| Pharmacology | 28 | 11.8 |

| Physiology | 30 | 12.7 |

| Parasitology | 19 | 8 |

| Biochemistry | 28 | 11.8 |

| Microbiology | 22 | 9.3 |

| Genetics | 26 | 11 |

| Immunology | 22 | 9.3 |

| Medical Physics | 20 | 8.4 |

| Biomedical Engineering | 16 | 6.8 |

The highest score was the creativity dimension (mean score of 2.35 ± 0.02), while the lowest mean score was for elaboration (mean score of 2.06 ± 0.02). The mean creativity score of the participants was 2.23±0.01.

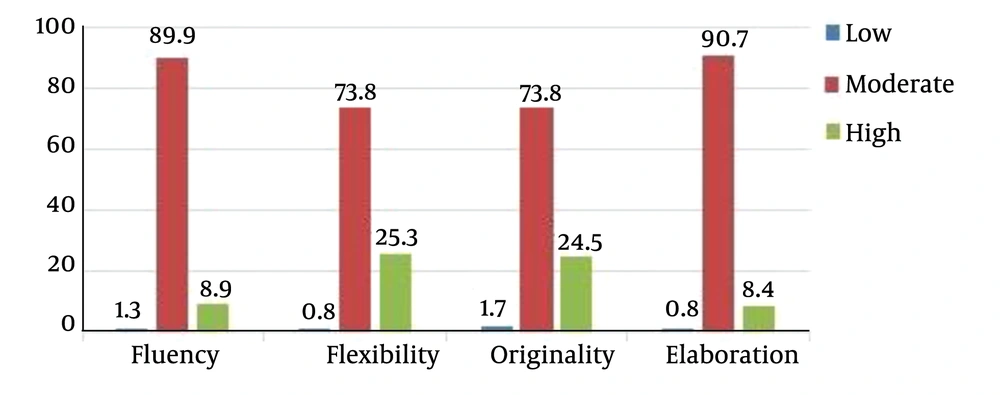

Table 3 indicates the descriptive characteristics of different sub-scales of creativity of the participants. Most of the participants (88.6%) obtained a moderate score for creativity. Only 1.7% obtained a weak score, and 9.7% obtained a high score.

| Variables | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) | Median | Maximum | Minimum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fluency | 2.17 | 0.02 | 2.18 | 3 | 1 |

| Flexibility | 2.32 | 0.02 | 2.36 | 3 | 1 |

| Originality | 2.35 | 0.02 | 2.37 | 3 | 1 |

| Elaboration | 20.6 | 0.02 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Overall | 2.23 | 0.01 | 2.20 | 2.97 | 1 |

Scores of participants separated by sub-scale are provided in Figure 1. Accordingly, most of the students obtained a moderate score. For those with a high creativity score, the highest performance was in flexibility and elaboration subscales.

As shown in Table 4, there was no difference between students' creativity scores in general and demographic variables separated by age, marital status, educational level, and gender, although it was not statistically significant.

| Variables | Number | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | 0.565 | |||

| Single | 189 | 2.22 | 0.02 | |

| Married | 48 | 2.24 | 0.02 | |

| Education | 0.642 | |||

| Master | 202 | 2.22 | 0.01 | |

| PHD | 35 | 2.26 | 0.04 | |

| Gender | 0.598 | |||

| Female | 128 | 2.22 | 0.02 | |

| Male | 109 | 2.23 | 0.02 | |

| Age | 0.875 | |||

| < 25 | 62 | 2.24 | 0.03 | |

| 25 - 30 | 148 | 2.22 | 0.02 | |

| 30 - 35 | 18 | 2.26 | 0.06 | |

| > 35 | 9 | 2.20 | 0.04 |

Table 4 shows the association between creativity and demographic variables, separated by gender, marital status, age, and education level. Concerning the subscales of creativity separated by demographic variables, the results of the Mann-Whitney test and t-test showed no difference in fluency and originality subscales according to the age, marital status, and education level, but it was not statistically significant (P-value > 0.05) (Appendix 1).

The results of the Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric test) showed no difference in fluency and elaboration, but were not statistically significant.

5. Discussion

In this study, the overall creativity score of participants was higher than average, and about 10% obtained a high score. Mardanshahi et al. found that most of the participants obtained poor and very poor creativity scores (8). However, Ebrahimi, who studied the students of Tabriz Azad University, reported scores higher than average (9). This discrepancy can be due to differences between programs, methods, educational environments of Azad University and State Universities, and the difference between curriculums of agricultural-related majors with other majors. Innovative teaching and learning methods in medical education, such as brainstorming, role-playing, competition, and games can develop creativity in students. Applying these techniques requires time and a lot of effort (10). Khodayari et al. investigated nursing students (both undergraduate and postgraduate) and reported that the mean score of participants was significantly lower than the mean score reported by Moshirabadi et al., who investigated the undergraduate nursing students of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (11).

In the present study, the score of all participants for all sub-scales was higher than average. Jahedi et al et al. found that the mean score of the elaboration sub-scale was higher than other sub-scales (12), while the mean score of flexibility was lower than other subscales. Jahedi et al. reported that electronic learning was associated with increased creativity and fluency among students. Sternberg reported that creative people are more flexible than others and non-stereotypical behaviors and heterogeneous attitudes are more common (13).

In this study, the mean scores of fluency, originality, and elaboration sub-scales were higher among females. However, there was no significant difference between students' creativity and its sub-scales among male and female students, which is consistent with the results of other studies by Mohammad Noori et al., Moshirabadi et al. Moreover, Khodayari et al. reported no significant difference between male and female students concerning the creativity score and its sub-scales (14, 15). Using Torrance's creative thinking test, Akinboi compared creativity talent in 30 high school male and female students. They reported that male students had a better performance in the flexibility subscale (16). Also, Rina et al., who studied gender differences in the creativity of Indian students, reported no significant difference (17). According to the results reported by Naderi et al., it seems that gender differences in creativity are reducing, and with the fundamental changes in society's attitudes, both genders have equal opportunities for growing their talents (18).

The mean score in fluency, flexibility, and elaboration subscales of couples was higher than their single counterparts, such as originality. In the present study, there was no significant difference between creativity score and its sub-scales based on marital status and age (Appendix 1).

In the present study, the mean score of fluency, originality, elaboration, and total creativity of Ph.D. students was higher than that of M.Sc. students, and both groups showed a similar flexibility score (Appendix 1). Khodayari et al. reported a significant difference concerning creativity and its subscales between undergraduate and postgraduate students; however, there was no statistically significant difference between subscales of fluency, elaboration, and originality (14).

Livingston argued that creating an empirical paradigm focused on fostering creativity only requires institutional interventions. As long as we solely follow the traditional pedagogies, old teaching methods, and theoretical lessons, there will be no room for new experiences, which are necessary for nurturing creativity (19). A study by Potter on university professors' perceptions of students' creativity reported that not prioritizing creativity is an essential obstacle for nurturing creativity in the education system. They mentioned organizational support as a significant intervention that boosts creativity in universities (20).

Parker argued that to better understand creativity, universities and higher education institutions should first value and respect it. Therefore, first, the creativity and its necessity for society should be well defined for universities and faculty members.

The current study had limitations, including using a self-report questionnaire to collect data, which are highly dependent on time and location. Therefore, caution should be taken when generalizing the findings. Also, the sample size of the present study was not sufficient. The authors recommend conducting further qualitative studies with a more profound perspective on creativity in the macro policies of universities.

5.1. Conclusion

Increasing creativity is associated with greater competitive advantages, resulting in the development and increased dynamic of a knowledge-based economy. Therefore, increasing creativity is of crucial importance for societies. Based on the findings of the present study, universities should pay more attention to providing specialized training to develop people, which can help them nurture their creativity.