1. Background

Competence refers to the ability to perform tasks with desired outcomes. Some studies have indicated that clinical practice competence among midwifery students is suboptimal (1). The clinical competence of midwives is directly linked to maternal and infant mortality rates (2). Educational programs play a pivotal role in achieving clinical competence (3).

Emerging methods have expanded the scope of clinical education (4). Educational technologies enhance the learning process by being adaptable and responsive to the learner’s needs (5) and are generally well-received by students (6). The utilization of educational software not only impacts students’ learning but also significantly enhances their performance in clinical evaluations (7).

Using videos serves as a crucial educational tool that reinforces prior learning (8). Learners benefit from the ability to review videos multiple times, which contributes to improved comprehension (5). Given the often substantial gap between acquiring skills and applying them in patient care, instructional videos are invaluable educational aids that provide three-dimensional information for skill recall (9). Video-assisted learning aids in reducing cognitive load, increasing learner engagement and enhancing the learning experience (10).

Instructional videos focusing on nursing skills, such as repositioning patients (8) and wound care, facilitate learning, pique students’ interest, and boost motivation (11). This resource proves especially valuable in situations where there is a shortage of instructors or equipment, serving as an alternative or supplementary method to enhance student learning (12).

Devi et al. demonstrated that students effectively learn through video-assisted instruction in addition to traditional demonstration methods (13). Although there is no substitute for hands-on training in clinical skills, instructional videos can complement these methods. A combination of teaching approaches can enrich the learning experience (13). Consequently, blended learning, which combines various methods, enhances the knowledge and skills of health care students and is often preferred due to its flexibility (14).

Blended learning can have a positive impact on student success, especially when employed to support distance learning (15). Studies have consistently shown the beneficial effects of blended learning on skills training in areas such as prenatal care, natural delivery, speculum placement, Pap smear (16), surgical skills (17), physical examination skills (18), and maternal health nursing (19). Given the researchers’ experience in teaching clinical skills using demonstration methods, their commitment to enhancing basic clinical skills training for midwifery students has led them to explore avenues for improving student learning.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to investigate the effect of using a combination of instructional video and demonstration methods of basic clinical midwifery skills on students’ performance and satisfaction.

3. Methods

3.1. Design and Participants

This quasi-experimental study was conducted on 41 midwifery students at Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran, utilizing the census method within October 2018 to July 2019. The inclusion criteria encompassed first-year midwifery students who were taking the midwifery principles and techniques course for the first time. The exclusion criteria included students who had participated in clinical training courses before or during the study. It is worth noting that the Hamadan University of Medical Sciences admits midwifery students in two semesters: October and February. As all the students were female, random selection was performed due to the limited number of students, with those admitted in October 2018 forming the control group and those admitted in February 2019 constituting the experimental group.

The sample size was determined using the following formula:

Considering the standard deviation of the clinical skill score in the two intervention and control groups (σ) was 3.67, the minimum significant difference (d) was 4.2, the confidence level was 0.95, and the statistical power was 0.90, the minimum sample size for each group was calculated to be 19 subjects (20).

3.2. Intervention

The study’s objectives were presented to the students at the study’s beginning, and written informed consent was obtained from them. The intervention took place over eight sessions, covering the period within October to December for the control group and within February to June for the experimental group. Each session had a duration of 2 hours. The selection of methods, including blood pressure assessment, intravenous treatment, injection, insertion of urinary catheter, use and removal of sterile gloves, prepping and draping for vaginal birth, hand washing, suctioning, and oxygen therapy, was based on the materials included in the Midwifery Principles and Techniques course curriculum.

The control group was divided into two subgroups, comprising 10 and 11 students, respectively. In each session, one of the midwifery instructors taught one of the fundamental midwifery procedures to the students using the demonstration method. This method is considered one of the most active teaching techniques, allowing individuals to acquire specific skills through observation. It involves using real objects for training and is commonly employed in courses with practical and technical components. The process for this method typically involves preparation, implementation, and follow-up (21).

In this study, the instructor initially established the teaching objectives and developed the necessary tools. Subsequently, she provided verbal explanations of the procedure and then executed it step by step. The experimental group was also divided into 2 subgroups, each containing 10 students. Their training comprised a combination of the demonstration method and instructional video. Three days before each session, the instructional video was shared with the students through a designated virtual channel, and they were asked to watch the video before attending the clinical session. Following this, the students received training during clinical sessions using the demonstration method. The conditions for training using the demonstration method were consistent for both groups, encompassing content, location, equipment, instructor, and the duration of the training. At the conclusion of each session, students from both groups practiced the procedure under the instructor’s supervision, and their performance was evaluated using a checklist.

The instructional videos were created within the Skill Laboratory of Hamedan Nursing and Midwifery Faculty. An instructional video is a multimedia training tool that combines audio and video elements, such as online lectures, demonstration videos, or documentaries (22). To produce these educational videos, two researchers collaborated with a senior midwifery student who had previously successfully completed the course and was not part of the study groups. These videos were filmed in the Skill Laboratory of the Hamadan Nursing and Midwifery School, with one video created for each procedure. The videos began by introducing the necessary tools and were then followed by a step-by-step demonstration performed by the senior student. One of the researchers provided narration for the demonstrations. The videos were subsequently finalized by adding titles and, in some instances, brief descriptions. To ensure the content validity of the educational videos, 5 faculty members from the midwifery department, along with the dean and vice-chancellor of the faculty, reviewed the videos and provided their feedback.

At the end of the semester, students’ satisfaction with and performance related to the educational method (demonstration or blended learning) were assessed in both groups. A satisfaction questionnaire was administered to the students by an expert in the clinical skills laboratory.

3.3. Data Collection Tools

Demographic information, including age, occupation, and marital status, was collected using a questionnaire. A 10-item scale was employed to measure satisfaction. The validity and reliability of this scale have been confirmed, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.79 and a correlation coefficient of 0.83 in Khoobi et al.’s study (23). Students’ satisfaction was assessed on a numerical scale ranging from 0 to 10 for each item, with the total score ranging from 0 to 100. In this study, the scale’s correlation coefficient was observed to be r = 0.94.

A checklist was used for each procedure during each session to evaluate students' performance. There were 8 checklists in total, each containing 5 - 10 items. The minimum and maximum scores for each checklist ranged from 0 to 5. These checklists were developed by 2 professors responsible for the course, and their validity (content validity ratio and content validity index > 0.80) and reliability (inter-rater reliability > 0.50) were confirmed in Refaei et al.’s study (24). In the current study, the inter-rater reliability exceeded 0.5 for all checklists.

Students’ overall performance was assessed through the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) at the end of the semester, which comprised four stations (Station 1: Blood pressure assessment and oxygen therapy; Station 2: Intravenous therapy and injection; Station 3: Applying and removing sterile gloves and hand washing; Station 4: Prepping and draping for a vaginal birth and insertion of a urinary catheter). Each station had an experienced inspector, and within each station, there were 2 procedures with identical scores. Students randomly performed one of these procedures. Each station allowed 5 minutes for students to complete the tasks, with the minimum and maximum scores in the OSCE ranging from 0 to 20. Criterion validity was employed to assess validity, and a significant relationship was observed between the OSCE score and the mean score of the courses (r = 0.55, P = 0.005). To determine the test’s reliability, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used, revealing an alpha value of 0.87 across stations.

3.4. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study received approval from the National Agency for Strategic Research in Medical Education and the Education Development Center of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (ethics code: 980824). Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the study adhered to ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or equivalent ethical standards. The purpose of the study was explained to the students and informed written consent was obtained from them.

3.5. Data Analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed to assess the normality of quantitative variables. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare the mean quantitative scores between the two groups; nevertheless, the chi-square test was utilized for comparing qualitative variables, such as occupation and marital status. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS software (version 16), and a significance level of 0.05 was considered.

4. Results

The study involved 41 students divided into 2 experimental and control groups. There were no significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of age, occupation, and marital status. The mean age of students in the experimental group was 19.42 ± 1.46 years; nonetheless, in the control group, the mean age was 20.25 ± 2.04 years (P = 0.496). None of the students was employed, and 90% and 95% of the students in the experimental and control groups were single, respectively (P = 0.520).

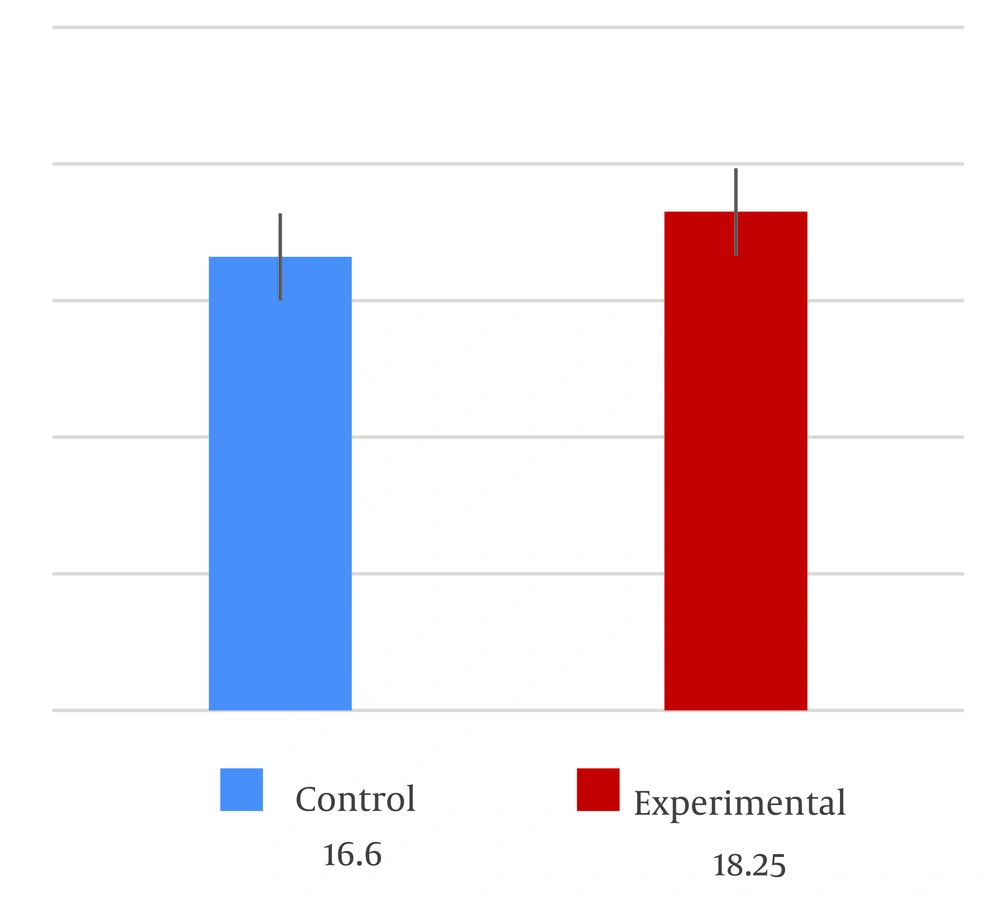

The mean scores for blood pressure assessment, intravenous therapy, injection, insertion of a urinary catheter, application and removal of sterile gloves, and prepping and draping for vaginal birth were significantly higher in the experimental group than in the control group (P < 0.001). Regarding the handwashing procedure, the mean score in the experimental group was slightly higher than in the control group (P = 0.380). The mean scores for suctioning and oxygen therapy in the experimental group were nearly equal to those in the control group (P = 0.604). There were no significant differences in the mean scores of these two procedures between the two groups (Table 1). The combined training group achieved significantly higher scores in the OSCE (P = 0.002) (Figure 1) and its stations (P < 0.05) than the demonstration method group (Table 1).

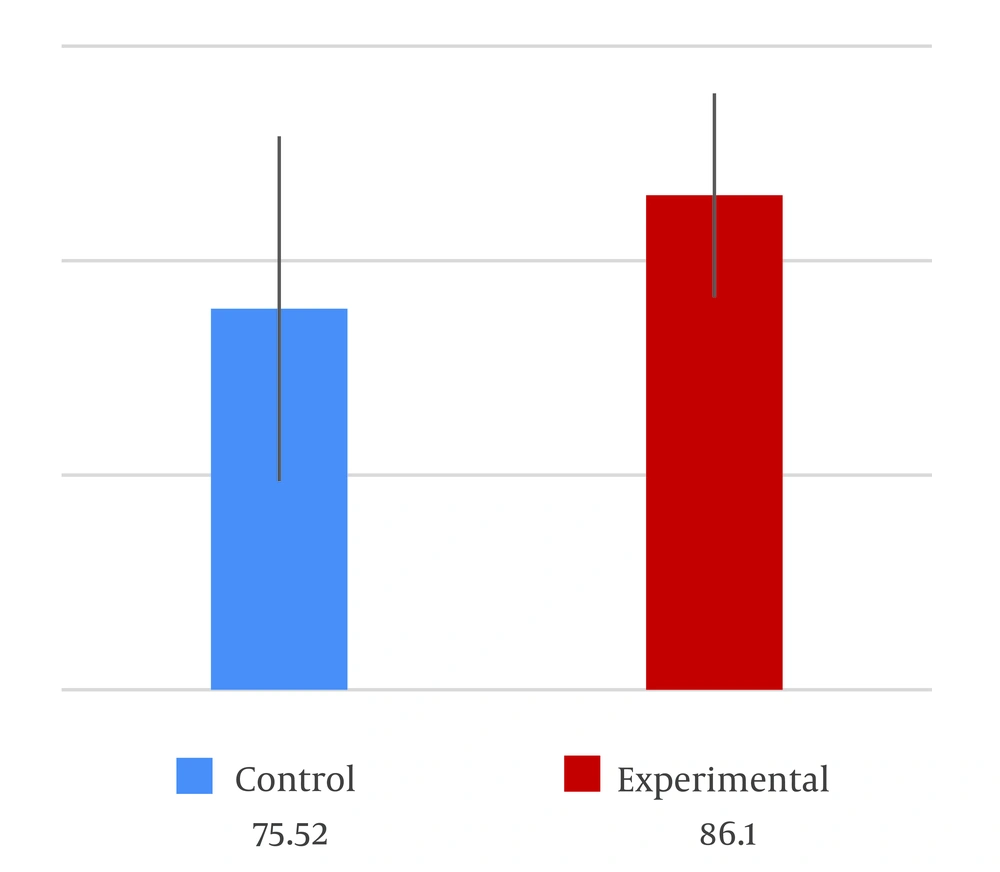

Students’ satisfaction with the educational method in the combined training group was significantly higher than in the control group (P = 0.027) (Figure 2). For all procedures, the students expressed higher satisfaction with the combined educational approach than the demonstration method. The combined training group also demonstrated significantly higher levels of satisfaction regarding the transfer of educational content and overall satisfaction with the training course (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Variables | Control Group (n = 21) | Experimental Group (n = 20) | P-Value b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure assessment | 3.57 ± 0.50 | 4.45 ± 0.26 | < 0.001 |

| Injections | 3.26 ± 0.56 | 4.6 ± 0.25 | < 0.001 |

| Intravenous therapy | 3.57 ± 0.42 | 4.50 ± 0.24 | < 0.001 |

| Urinary catheter insertion | 3.04 ± 0.58 | 4.45 ± 0.25 | < 0.001 |

| Applying and removing sterile gloves | 3.60 ± 0.89 | 4.61 ± 0.40 | < 0.001 |

| Prepping and draping for vaginal birth | 4.19 ± 0.51 | 4.62 ± 0.29 | 0.004 |

| Hand washing | 4.11 ± 0.73 | 4.27 ± 0.81 | 0.380 |

| Suction and oxygen therapy | 4.14 ± 0.59 | 4.10 ± 0.32 | 0.604 |

| First station | 4.16 ± 0.5 | 4.52 ± 0.52 | 0.030 |

| Second station | 4.25 ± 0.4 | 4.57 ± 0.57 | 0.040 |

| Third station | 4.10 ± 0.52 | 4.53 ± 0.43 | 0.007 |

| Forth Station | 4.03 ± 0.5 | 4.56 ± 0.3 | 0.001 |

| Total performance | 16.60 ± 1.60 | 18.25 ± 1.58 | 0.002 |

Comparison of Performance Mean Scores Between Two Groups a

| Variables | Control Group (n = 21) | Experimental Group (n = 20) | P-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total satisfaction | 75.52 ± 16.07 | 86.10 ± 9.50 | 0.027 |

| Adequate time to learn | 7.09 ± 2.04 | 8.15 ± 1.26 | 0.088 |

| Facilitating the transfer of educational content | 7.19 ± 1.86 | 8.65 ± 0.87 | 0.009 |

| Facilitating answering questions by the instructor | 8 ± 1.51 | 8.35 ± 1.38 | 0.316 |

| Instructor access | 7.90 ± 1.54 | 8.75 ± 1.33 | 0.52 |

| Increasing motivation to learn | 7.90 ± 1.89 | 8.85 ± 0.98 | 0.137 |

| Improving the quality of education | 7.85 ± 1.98 | 8.90 ± 0.91 | 0.090 |

| Satisfaction with the training course | 7.28 ± 2.19 | 8.90 ± 1.02 | 0.026 |

| Meeting students’ expectations | 7.66 ± 1.71 | 8.55 ± 1.14 | 0.086 |

| Saving cost and energy | 7.19 ± 2.63 | 8.60 ± 1.23 | 0.133 |

| Saving time | 7.33 ± 2.22 | 8.40 ± 1.53 | 0.81 |

Comparison of Student Satisfaction Scores Between Two Groups a

5. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the effect of a blended teaching method utilizing video and demonstration techniques on basic procedures in midwifery. The results of this study indicated that student performance in procedures, such as blood pressure assessment, intravenous therapy, injection, insertion of a urinary catheter, application and removal of sterile gloves, and prepping and draping for vaginal birth, was significantly better in the combined training method group than in the group that received only the demonstration method. Farahani et al. conducted a study in which an 11-minute instructional video was used to teach blood pressure measurement to pharmacy students in their final semester. The results showed that 95% of the students found the video to be valuable, and all students believed it should be incorporated into their training curriculum. Additionally, 100% of the students recognized the instructional video as a helpful tool in improving their practical blood pressure measurement skills (25).

Pilieci et al. conducted a study indicating that when teaching sterile surgical techniques to first-year medical students, video instruction outperformed demonstrations in terms of enhancing knowledge acquisition. They suggested that assessing performance rather than just knowledge is crucial (26).

Wong et al. demonstrated the effectiveness of educational videos when combined with the demonstration method for teaching psychomotor skills to second-year dental students in dental anesthesia procedures. The study revealed that the use of educational videos was both valuable and well-received by students, with the number of video views correlating with practical performance scores. Notably, narrative videos with background music attracted more views (27). Ramlogan et al. emphasized that while video-based training alone in clinical periodontology might have limitations, it can be highly effective when supplemented with appropriate learning activities (28).

In the present study, there was no significant difference between the 2 groups in terms of students’ performance in hand washing and oxygen therapy, and both groups achieved high scores in these procedures. Bawert and Holzinger conducted a study demonstrating that a video tutorial on hand washing improved students’ recall of the procedure, and students positively evaluated the presence of the video on the faculty’s website. Although the students’ scores did not change significantly, they achieved better results, similar to the findings of the current study. The authors suggested that combining various teaching and learning formats, such as videos along with textbooks or lecture notes, was effective in enhancing the efficiency of learning (9).

Parandavar et al. observed that the blended training method significantly improved the final performance of midwifery students, compared to the traditional method, particularly in emergency midwifery education (29). Similarly, Saun et al. demonstrated that instructor-made videos were as effective as standard videos in teaching chest intubation (30).

One of the advantages of this study was the use of a blended teaching method in the midwifery learning process, which has the potential to serve as an educational approach during times of pandemics, such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, when physical attendance at the university and clinical environments might be limited. Additionally, the study’s strength lies in measuring the impact of the combined method on students’ performance; however, some similar studies solely assessed knowledge through tests. Furthermore, the study employed a valid and reliable checklist to evaluate students’ performance in each procedure.

5.1. Limitations

However, there are several limitations to this study. Due to the small number of students, randomization was not feasible, and the study had to be conducted over two consecutive semesters, potentially leading to information leakage and affecting data integrity. Another limitation was the absence of a pre-test to assess students’ abilities before implementing the intervention, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the study did not investigate the long-term retention of skills or the applicability of the combined training method to other clinical procedures. To ensure that students watch the videos, it might be beneficial to require them to submit a summary.

5.2. Conclusions

In this study, the use of instructional videos and demonstrations as a combined educational method in teaching basic midwifery clinical skills resulted in improved student performance and satisfaction. It is recommended that this method be extended to a larger student population and applied to the training of other clinical midwifery skills, such as intrauterine device (IUD) insertion, Pap smear tests, and vaginal delivery.